-

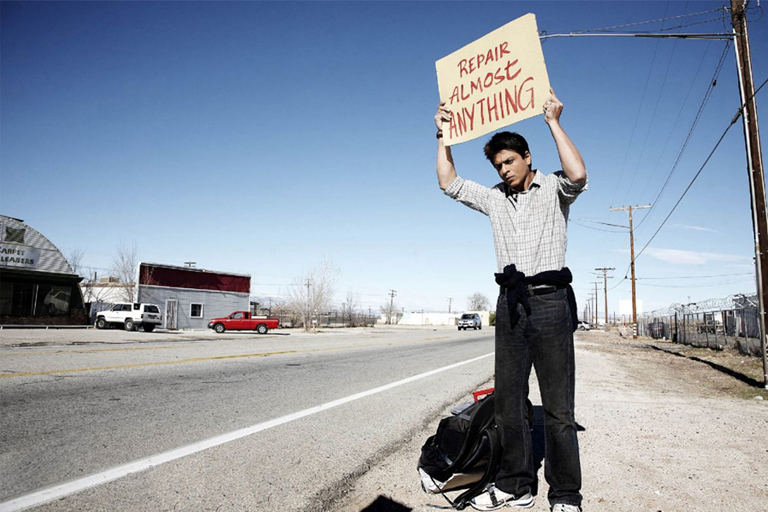

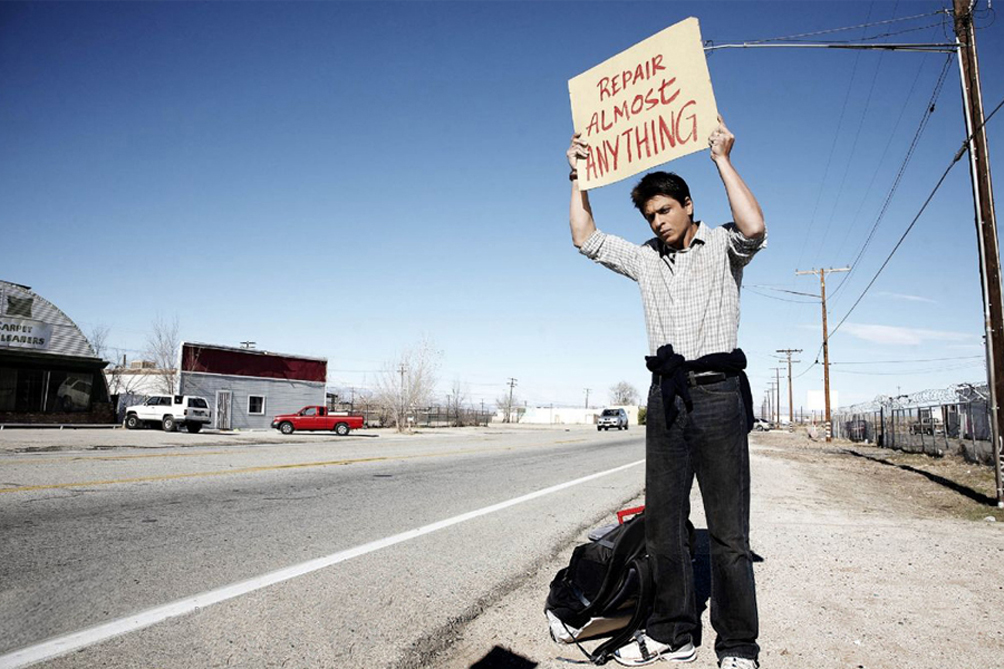

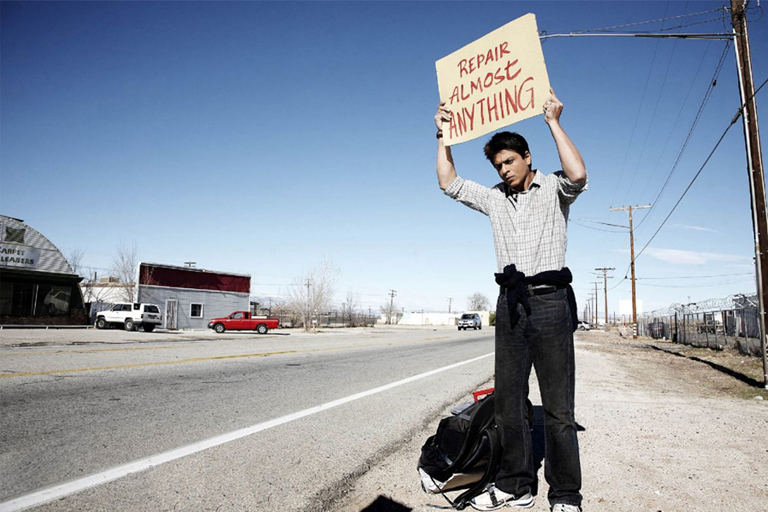

Shah Rukh Khan in My Name Is Khan (c) Fox Star Studios

Shah Rukh Khan in My Name Is Khan (c) Fox Star Studios

The Supreme Court delivered a critical judgement on the 26th of September 2012. It also uncannily quoted Shahrukh Khan’s character from a Karan Johar film. Supreme Court Advocate Karuna Nundy tells you what to make of it

“My name is Khan, and I am not a terrorist”, Justice Chandramauli Kumar Prasad quoted the Karan Johar film in his judgment on Wednesday, as he acquitted 11 Muslim citizens accused in a case under the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) . The case before the Supreme Court was tough: investigating agencies claimed they had seized 46 AK-56 rifles, 40 boxes of cartridges, 99 bombs, 110 fuse pins and 110 magazines in Ahmedabad from the people accused. The guns and bombs, the prosecution said, were later distributed to kill and terrorise the Hindu community during the Jagannath Rath Yatra.

The story could have been of the unsung heroism of police officers saving celebratory pilgrims, as the drums and dancing beat their way to a frenzied pitch while sweet boys on the Rath dressed as little gods passed unharmed.

The Supreme Court rejected the prosecution’s story. The TADA conviction by the lower court was based solely on the “confessions” of the accused people, in police custody. The police officers handling the case had ignored the safeguards TADA itself provides: “confessions” and other information about the alleged crimes were recorded by junior officers without the prior approvals of the District Superintendent of Police. The “confessions” therefore, were to be ignored.

Storytelling lies at the heart of justice. Competing stories are told in the courtroom, the one that fits the evidence and the law best, wins. Judges exercise discretion in each case though; especially in the Supreme Court which is allowed by the Constitution to ignore some of the procedural rules lower courts are trammeled by so that Judges can do “complete justice” in each case. Imaginative empathy, remembered from stories outside court may claim space then, in the judicial mind.

Stories on justice surround us, in the newspapers and on television, in literature, on Facebook and Twitter, our childhood narratives, brawls on the street. But the Queen of Hearts of Indian storytelling is cinema. Rang De Basanti moved a generation of middle class city-dwellers onto the streets, bearing candles, demanding justice; Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi showed urban India why a generation of privileged Indians became Naxals; Damini shaped some of India’s most ardent male feminists.

My Name is Khan took a crack at it, but due process for a person suspected of terrorism is a harder story to sell when the people accused aren’t especially heroic or endearing. The case before Justices Prasad and H.L. Dattu included the brother and associates of Abdul Latif Sheikh, allegedly a “fountainhead of the weapons…a notorious criminal”. Latif was killed in an encounter with the Gujarat police. His brother made radiators for sports utility vehicles and the evidence against him was thin, he was worried that he too would soon be killed in an “encounter”. TADA was repealed in 1995 because tens of thousands of people were regularly put through the slow harsh noose of police violence and jail, though years – sometimes decades – later 98% were acquitted.

The Supreme Court is not an emotional place, but it seats men and women with hearts as well as heads; justice, fundamental rights and Article 142 of the Constitution require them to use reason as well as imaginative empathy with their fellow citizens. We don’t know if Justice Prasad thought My Name is Khan was long and overly simple, or whether he thought the Filmcity version of a Georgia hamlet was tacky. We do know that the story in those ten words of film dialogue resonated with his idea of justice and brought to us 11 innocent men, their necks branded by the rope burns of an 18 year terrorist trial.

Storytelling Justice

OpinionSeptember 2012

By Karuna Nundy

By Karuna Nundy

Karuna Nundy is an advocate in the Supreme Court of India as well as a member of the New York State Bar Association. She represented one of the people accused in the case she writes about here, in a bail proceeding in 2006. Specializing in commercial dispute resolution and human rights litigation, she also advises United Nations agencies and governments of various countries to help them conform their laws to international and constitutional legal standards. At the Supreme Court of India she is leading litigation concerning the rights of the Bhopal Gas victims. Nundy was on the National Advisory Council's drafting committee for crucial proposed legislations such as the Right to Food Bill.