-

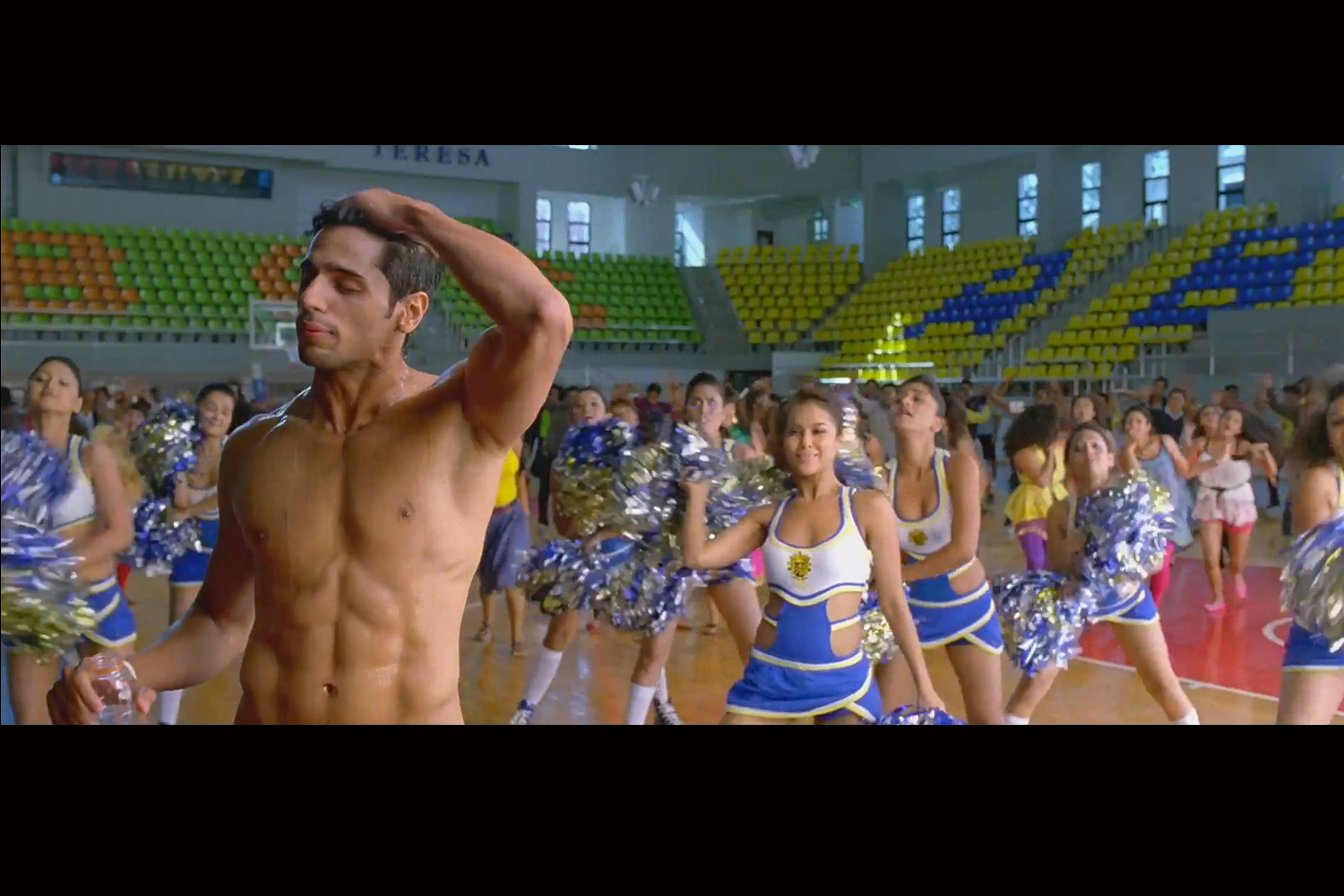

Siddharth Malhotra and Varun Dhawan in Student Of The Year (c) Dharma Productions

Siddharth Malhotra and Varun Dhawan in Student Of The Year (c) Dharma Productions -

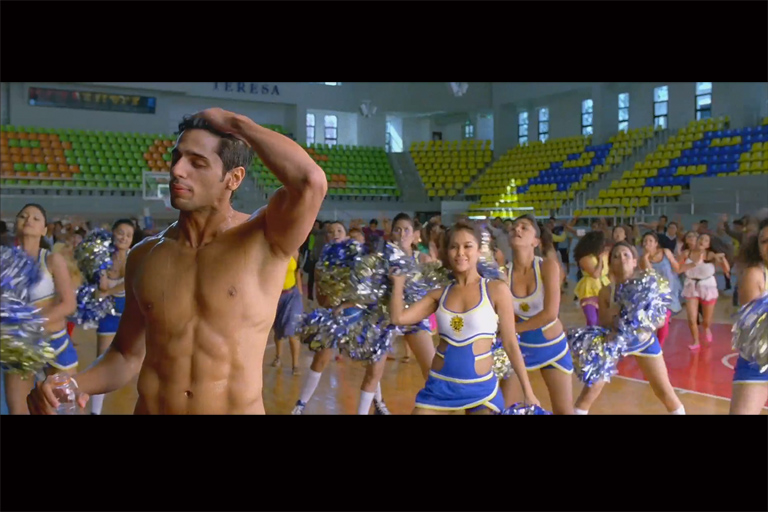

Siddharth Malhotra in Student Of The Year (c) Dharma Productions

Siddharth Malhotra in Student Of The Year (c) Dharma Productions -

Poster of Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar

Poster of Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar -

A still from Chittagong

A still from Chittagong -

Poster of Ustad Hotel

Poster of Ustad Hotel -

A screenshot from Luv Shuv Tey Chicken Khurana (c) UTV Spotboy

A screenshot from Luv Shuv Tey Chicken Khurana (c) UTV Spotboy -

Kunal Kapoor in Luv Shuv Tey Chicken Khurana (c) UTV Spotboy

Kunal Kapoor in Luv Shuv Tey Chicken Khurana (c) UTV Spotboy

Eat, Drink, Shoot, Cycle

Should any movie take its own McGuffins seriously? If it does, you could end up with Student of the Year. And its Ayn Randish undercurrents. The bicycle race in Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar was dead serious but Mansoor Khan never really bothered explaining why, and that somehow made it more plausible. SOTY takes itself so seriously that there isn’t a single memorable song or dance in a movie choreographed by Farah Khan (whose first outing and best outing were high school musicals) and Vaibhavi Merchant.

So seriously that we end with a gay Hunger Games, in the climax of which Sudo (Kayoze Irani) seems to be accusing the Dean (Rishi Kapoor) of punishing the students because his gayness has made him lonely, bitter and without entertainment options. No wonder the Dean retired after this particular batch. If Sudo doesn’t understand that life doesn’t get better than watching Siddharth Malhotra emerge like Botticelli’s Venus from a swimming pool in Thailand, the education system has failed him.

How seriously should a revolution-movie take its revolution? When it’s eighty years after the fact and is in its second cinematic iteration, I suppose it’s quite okay for a movie to take its revolution seriously. Instead, Chittagong fails to ask a single question of received jingoistic history and (like SOTY) fails to create a single scene that you haven’t already seen over and over again in dozens of movies. An earnest soundtrack and dead bodies are not the same as seriousness, although it might be easy to mistake one for the other.

So now we come to it. Hormones and radicalism are alright, but the question we all want answered is: How seriously should a food movie take food?

Not as seriously as Director Anwar Rasheed and Writer Anjali Menon. The Malayalam movie Ustad Hotel begins swiftly, surefooted, funny and poised, at its best in a wicked postcard shot of four young sisters drinking tea under a patio umbrella against the Dubai skyline. It’s SATC: Hijab Edition. In its cool subversiveness, this shot beats hands down even the fetching heroine Shahana’s (Nithya Menen) sudden appearance as a rocker in a headscarf.

Ustad Hotel had so much going for it. It was going to be one of our few food movies. It was also going to be that movie with Muslim characters you were waiting for: no one is suspected of being a terrorist, no one has anxiety about being a Muslim, and as far as I can recall, there are no tense namaaz scenes. My concentration only began to fail when I realised that the Malayali Muslim uber-social I was hoping for was getting all Sufi on me. After poor Thilakan (in his last appearance) started talking about dargahs and fez-wearing dervishes began twirling on the Kozhikode beach in front of TV cameras, I needed to lie down for the feeling to pass.

So what do we have? Faizi (Dulquer Salmaan) has been brought up by his four ithathas after his mother died. Growing up in Dubai in the household of a stern and money-minded father, he wasn’t really prepared for the loneliness of life after his four sisters got married. He cons his father into sending him to study in Switzerland. A few years later, when his father has engineered an alliance between Faizi and the daughter of another Kozhikode tycoon, the cat’s let out of the bag: all those years of hanging out with his sisters in the kitchen made Faizi really passionate about cooking and so, no, he wasn’t earning a Swiss MBA all this while. He was in culinary school.

His father, still smarting from his own childhood embarrassment of being the son of a beachfront restaurant owner, explodes. No way is he going to let Faizi take up a position in a London restaurant. And without his passport and credit cards, where is his son going to run to anyway? As it turns out, pretty Faizi has a small plan. He runs for temporary refuge to his grandfather who runs Ustad Hotel — the source of Faizi’s father’s shame.

That we barely get to see the four ithathas again is part of the problem, but mostly the problem is that old food-movie problem. Ustad Hotel‘s biryani is not just biryani. It’s how Faizi becomes a man, gets wild and gets a life. He might think for a while that making fusion cuisine is his thing but in the end he opts out of London and nouvelle vague in favour of his grandfather’s legacy. Food movies refuse to admit that sometimes a sulaimani is just a sulaimani is just a glass of black tea. Paul Giamatti goggling at glasses of Pinot Noir gets old and so do descending arcs of tea framed by sunsets on the beach. To be fair, not everybody feels suicidal in the middle of Masterchef Season 55 when the participants are talking gravely of their mistakes and ‘learnings’ from Season 34. So, maybe, it’s just me.

I didn’t go to Luv Shuv Tey Chicken Khurana expecting to see a great food movie— one that’s about food but isn’t about foodies. And what a humbling I’ve had. Director Sameer Sharma navigated Luv Shuv… cleverly and far, far away from the disastrous shoals of the genre—no Debbie Does Salad–style shots of paranthas and butter here—and except for one instance (more of which later), he resists drawing any homilies from cooking.

Like Ustad Hotel, Luv Shuv… has a grandfather (Vinod Nagpal) who owns a famous dhaba, a London-loving grandson and a local girl with chutzpah. But what a subcontinent of difference. Ustad Hotel takes a bizarre sidetour of poverty in Tamil Nadu and gives the grandfather those qawwali feelings to keep us warm at night. Luv Shuv… gives the elder Mr Khurana senile dementia and a tendency to fart. Faizi walks about sweetly and has London sous chef and Paris exec chef jobs falling into his lap. Our Punjabi hero Omi Khurana chloroformed his grandfather to get to London and would chloroform him again to return to London and his subsistence-gangster lifestyle. And now that his grandfather is no longer in the world of the sentient there is no one in the Khurana family who can cook at all. Omi’s chachiji is the first chachiji in the history of chachijis who cannot cook.

When Luv Shuv… does a ‘colourful’ cast, it doesn’t do generic boys with generic Rasta ambitions on Kozhikode beach. Ustad Hotel becomes a tourist trap of visual cliches while Luv Shuv… is so confidently grounded in its small-town Punjab locale that it can afford to carelessly toss in an odd Bengali widow (best widow since Kati Patang); parochial murmurs were rising from the audience—What is this bangalan doing here?—long before the movie did any explaining. And just as Ustad Hotel would benefit from a spinoff called Ithathas and Co, Luv Shuv… could easily branch into a movie about Lovely (the heroine’s brother), his kachcha business and his real estate ambitions.

***

Food movies have a tendency to turn us on with the elaborate and decadent, and then tell us that life is actually about the simplest of tastes: Roux‘s hot chocolate in Chocolat, Auguste Gusteau’s eponymous Ratatouille, or the eggs and bread in Big Night that the brothers eat after making complicated timpano. But Luv Shuv… doesn’t even fetishise simplicity like the brilliant new documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, where viewers drink the Kool-Aid so quickly and so deeply that we are united in our scorn for ignorant customers who walk in and ask Jiro for dessert (die, infidel, die!).

In Luv Shuv… the characters eat ordinary meals without looking like, to borrow a phrase, Orgasmo-Adulto-Escape from the Zoo. They chop onions without sounding like Kahlil Gibran. Kunal Kapoor and Huma Qureshi cook together without succumbing to marinated chicken a la the pottery scene from Ghost. Sameer Sharma must have the self-control of a zen master. Well, almost.

Here’s the bit in which Sharma (sorry) chickens out. Most food movies also become treasure hunts for the secret ingredient. And the secret ingredient is always love. This is true of Ustad Hotel (every sulaimani needs a bit of mohabbat in it, the stars are God’s daisy chain, etc.) and most other food movies.

Luv Shuv… has an audacious, thrilling secret ingredient that makes Chicken Khurana brilliant (it isn’t heeng, you loser, stop guessing). But Luv Shuv… takes this triumph of plot and then decides that its secret ingredient should be love too— in case love felt bad and went home. This momentary cowardice apart, this is a prince among food movies, made by people who’ve perhaps actually stood in front of a stove trying to make sure the scrambled eggs aren’t too wet, too dry or burnt their phulkas or destroyed their crème brûlée with a pint-sized flamethrower. They know that the secret ingredient of cooking isn’t love. It’s Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours of practice. It’s why Julia didn’t want to speak with Julie. And it’s why Omi Khurana’s chicken is alright in the end, not great. And that’s the best thing about the movie.

The TBIP Take

OpinionNovember 2012

By Nisha Susan

By Nisha Susan

Nisha Susan is a writer and critic based in New Delhi. She was Features Editor at Tehelka magazine and has worked for several non-profits. Her short fiction has been published by Penguin and Zubaan and she's currently working on a novel and a book on Malayali nurses. Her expectations of cinema were permanently raised from watching pulp films as a three-year-old in her grandfather's village theatre.