-

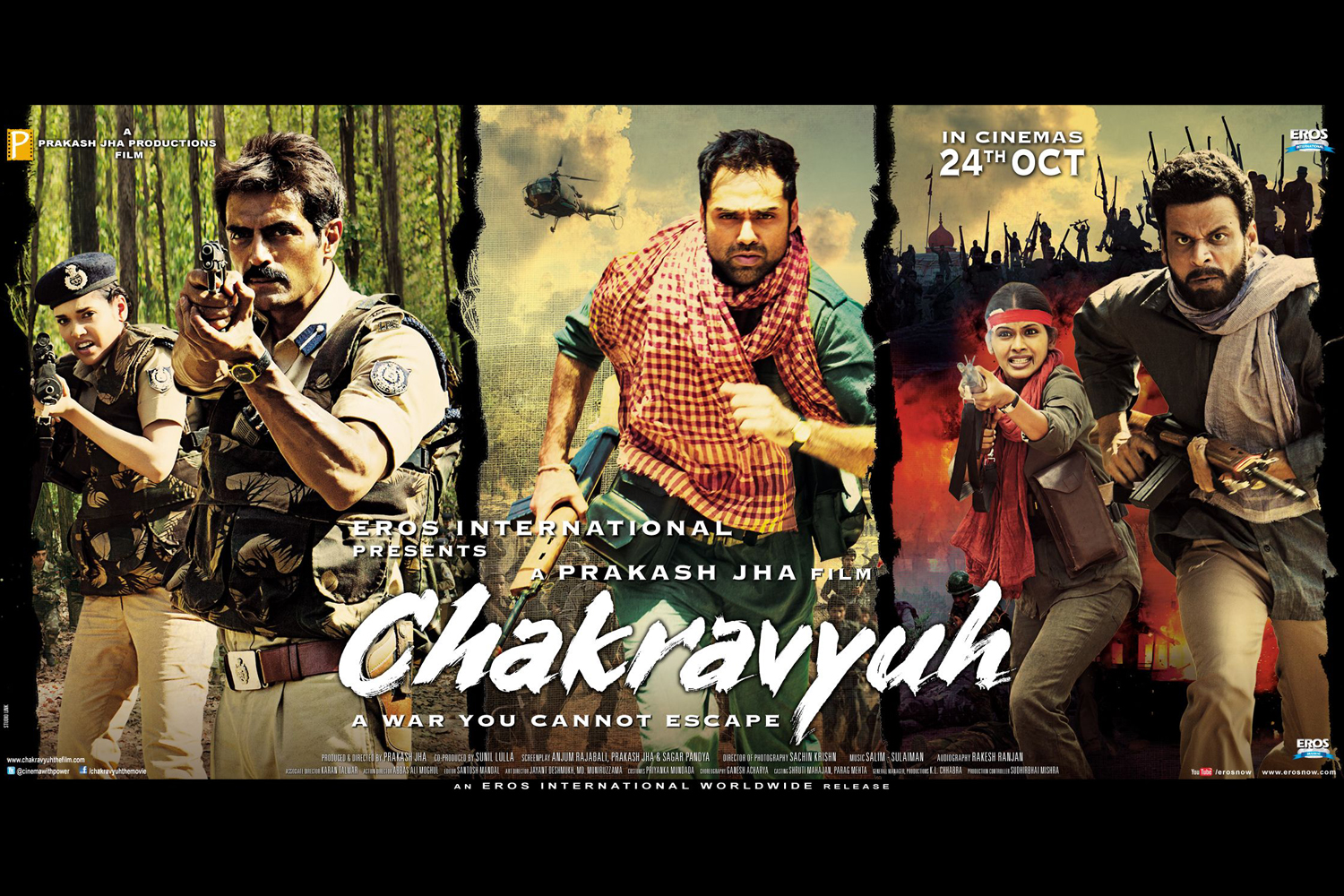

Poster of Chakravyuh

Poster of Chakravyuh -

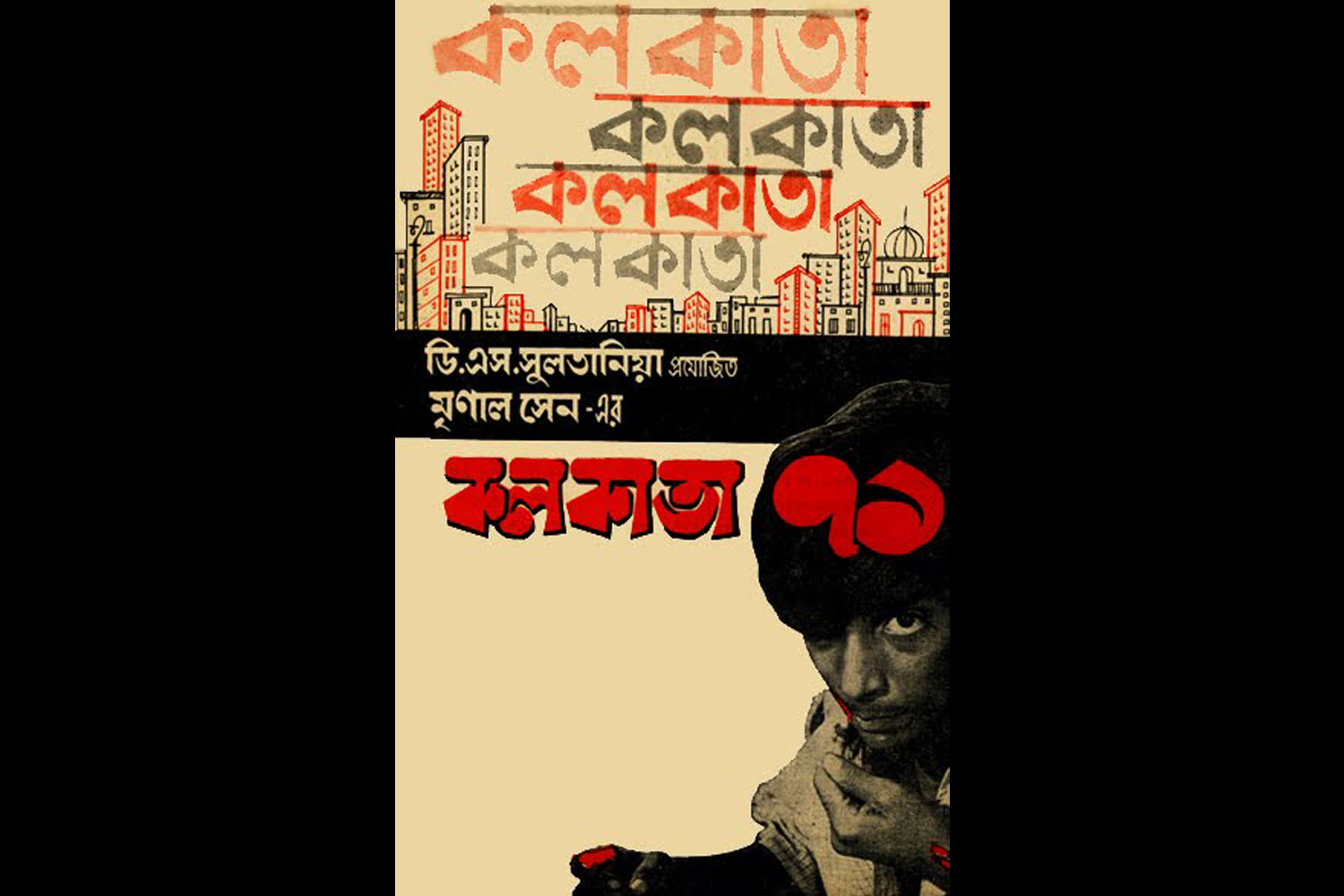

Poster of Calcutta 71— directed by Mrinal Sen

Poster of Calcutta 71— directed by Mrinal Sen -

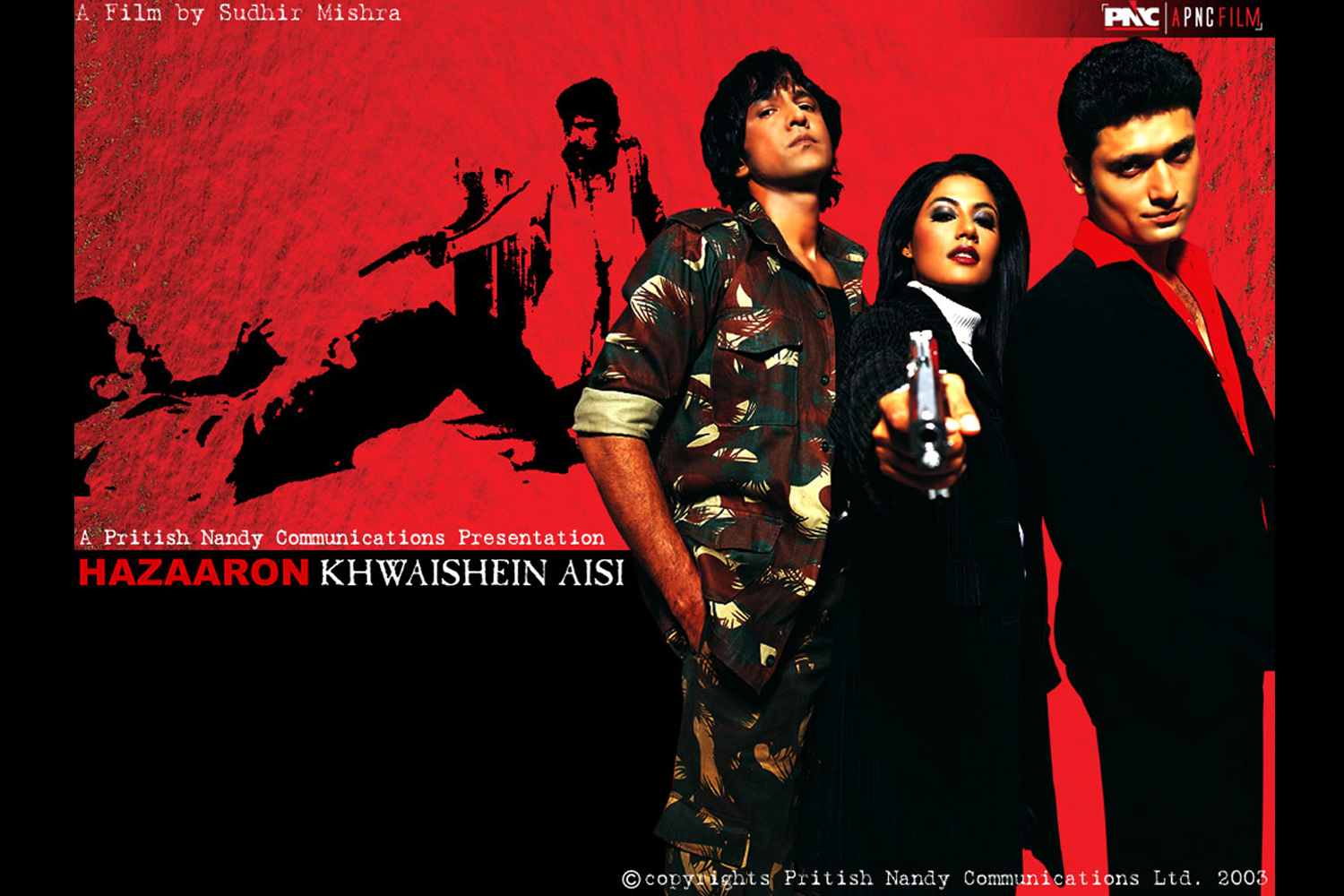

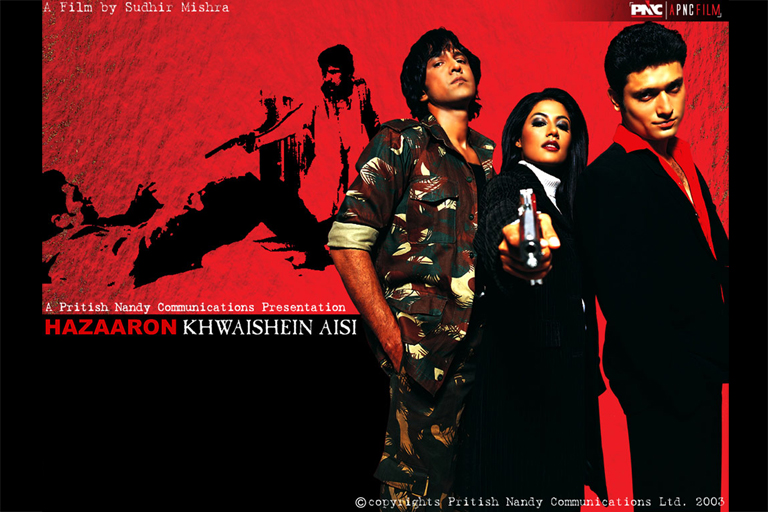

Poster of Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi

Poster of Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi -

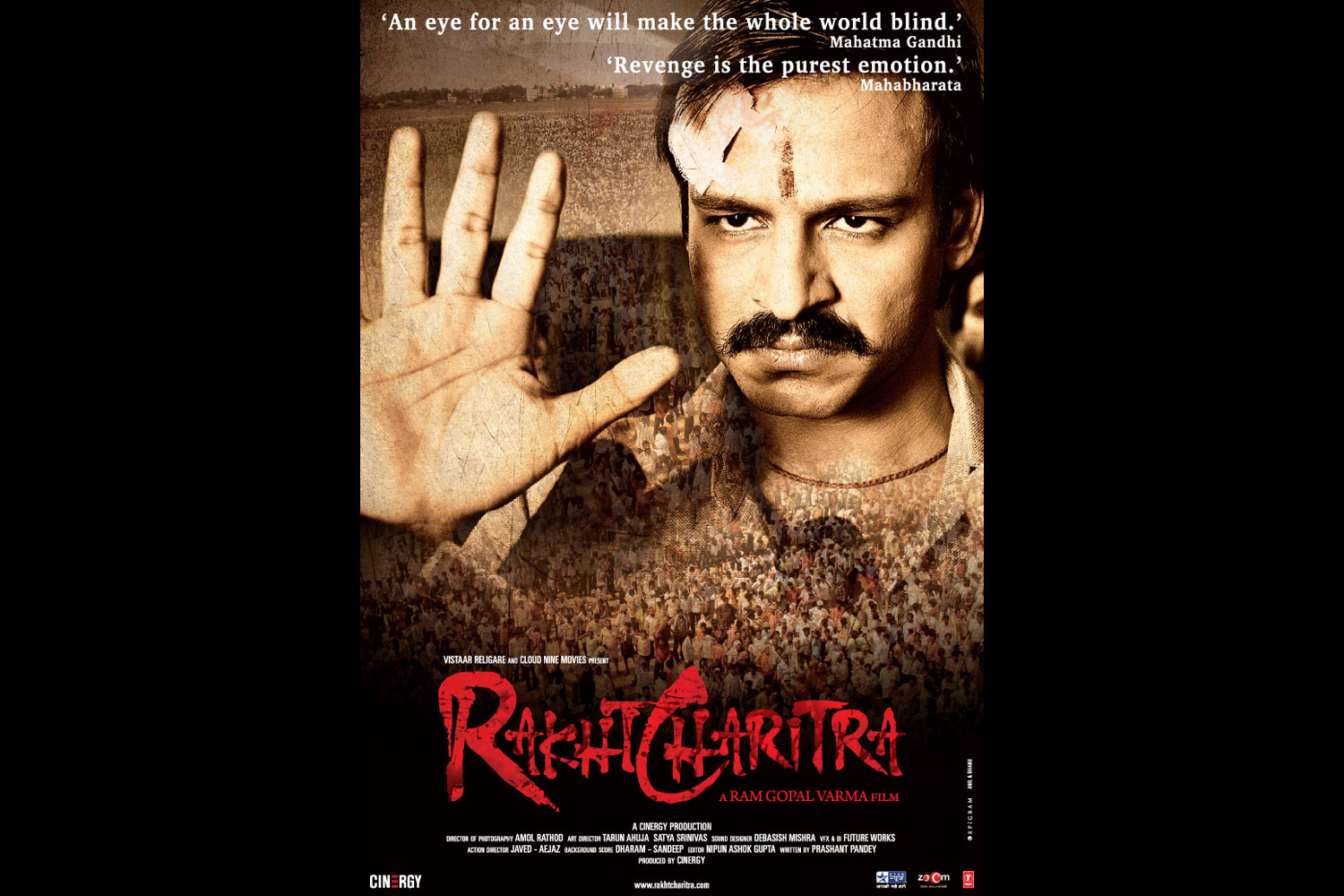

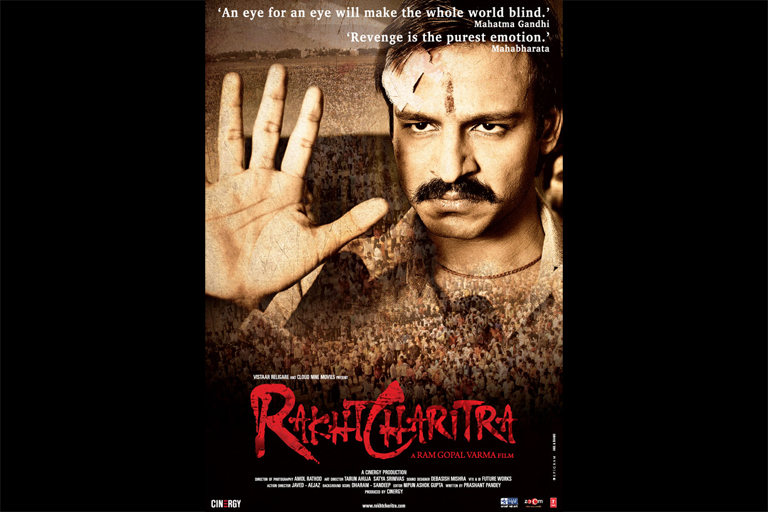

Poster of Rakht Charitra

Poster of Rakht Charitra -

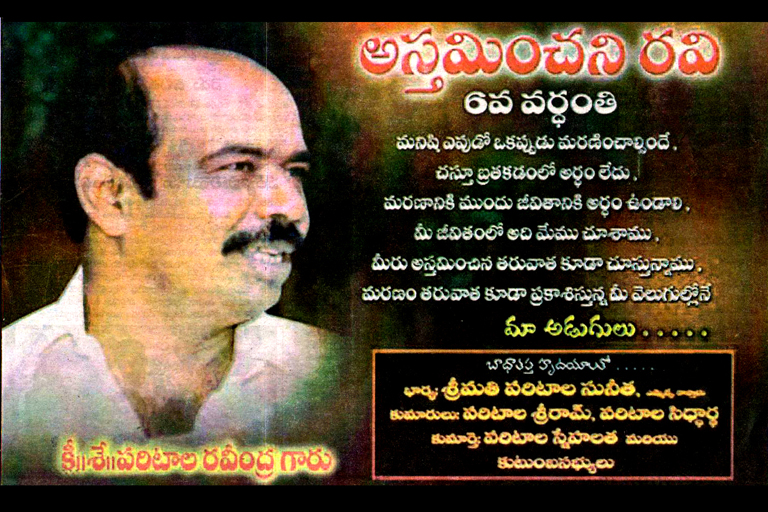

Photograph of Paritala Ravindra

Photograph of Paritala Ravindra -

on a political poster

on a political poster -

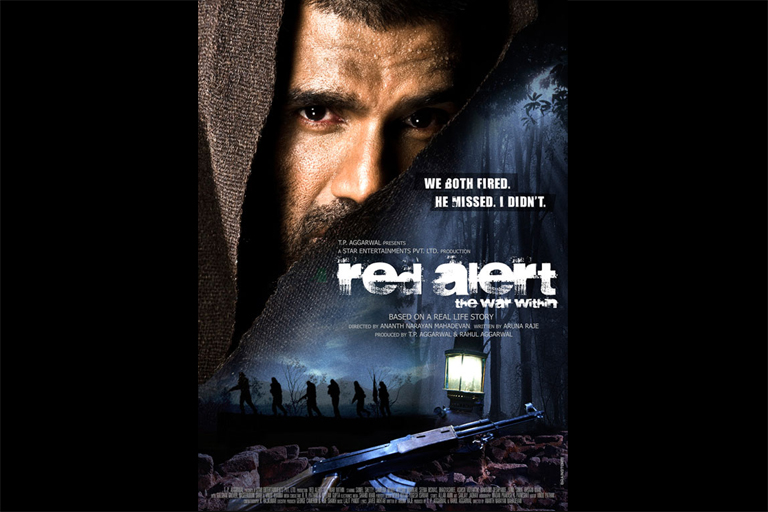

Poster of Red Alert: the War Within

Poster of Red Alert: the War Within -

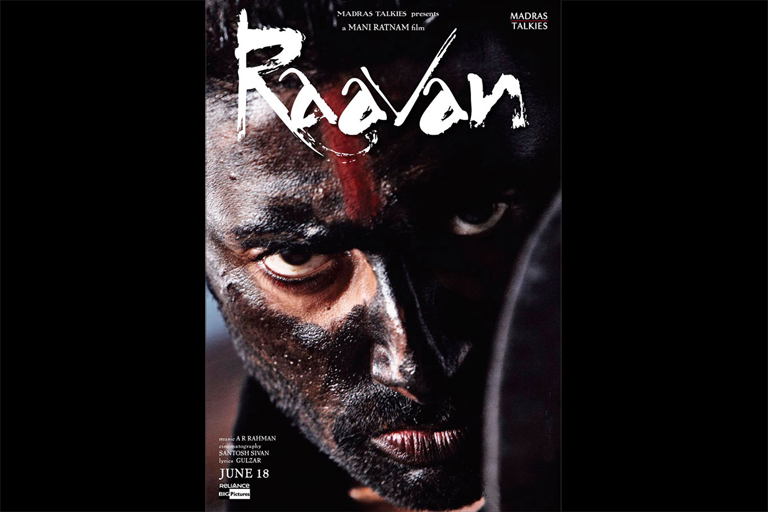

Poster of Raavan

Poster of Raavan

Hindi films portraying Naxalism have re-reported the headlines but missed the nuances argues Agnitra Ghosh

Naxalism is back in the metros, via Mumbai, on a big screen near you, this time with Prakash Jha’s Chakravyuh. The film is ‘inspired by’ contemporary events such as the arrest of top CPI (Maoist) leader Kobad Ghandy, the killing of 76 CRPF jawans in Dantewada, corporate land grab and the exploitation of natural resources. Chakravyuh narrates the story of two friends set against the background of the “biggest internal security threat” of the country in recent times.

For over 40 years since the emergence of the Naxalbari rebellion, cinema has drawn inspiration from the rupture caused by this iconic movement in Indian political history. The most prominent instances of the portrayal of the turbulent period of the seventies came from regional language films, especially from Bengali cinema, in the works of Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak and Buddhadev Dasgupta. It is interesting to note an almost complete absence of any direct representation of the movement in Hindi films made between the 1970s to 1990s.

In the last decade, however, Hindi cinema seems to have woken up to Naxalism, or Maoism, as it is more commonly known today. A number of films such as Lal Salaam, Hazaaron

Chakravyuh is a case in point. The trailer attempts to posture it as a film on a ‘serious issue’ by using lines like “In the World’s Largest Democracy” and “A War Has Begun” and a shot of a map with Maoist hit areas marked out in red. Chakravyuh’s promotion also ran into a controversy, when Jha received a legal notice from the Birla Group of companies over the controversial lyrics of the Mehangai song. However, the Supreme Court allowed the release of the song, so long as the film carries explicit written disclaimers on the screen saying it meant no offence. The controversy around the song and festival screenings, however, helped label the film as different from regular commercial cinema in mainstream media. Facebook pages on Chakravyuh (the official page and fan pages) have also emphasized the off-beat nature of the film, by putting out that it has non-mainstream actors in it, and a “social message”. Similarly, promotions of films like HKA, Red Alert… and Raavan have also showcased their screenings in national and international film festivals to maintain a distance from the mainstream.

Moving to the film itself, Chakravyuh

The theme of Naxalism has also been used in fairly straightforward action films like Tango Charlie, Chamku, Ra

Then there are films like Mani Ratnam’s Raavan, which don’t really seem to be attempting to portray Naxalism at all. Yet, there were reports in the popular media, prior to the film’s release, of protagonist Abhishek Bachchan’s character being modeled on Kobad Ghandy. Some such reports supported this claim by noting how the presence of a strong element of contemporary history (terrorism, communal riots, the North East insurgency) was a part of Ratnam’s signature style and by the fact that a team of researchers was appointed to get information about Ghandy’s life for the film. Though there was no mention of Naxalism in the film and it was hard to draw any similarities between Abhishek’s character and Ghandy, Maoism probably did contribute to Raavan‘s image of a ‘serious, issue-based film’. Using the name of Ghandy may have helped the film’s promotion machinery to connect it to the persisting media buzz around the arrest and trial of the top Maoist leader.

The ‘non-mainstream’ films on the theme of Naxalism are often marked by innovative formal strategies, but what gets overlooked, almost every time, is the politics of these films. In most of these films, Naxalism is just a background to narrate conventional stories. For example, in HKA, the Naxalbari Movement becomes only a canvas to facilitate the narration of the story of three friends during the turbulent times of seventies. Chakravyuh, though, attempts to ponder over the issue of Naxalism; yet in the end it becomes more about ethical dilemmas in the relationship between two friends. Jha views Naxalism as morally attractive, being sympathetic to the radical cause; yet the militant ideology is reduced to a tag, that might attract urban filmgoers. This is because while Chakravyuh constantly refers to real happenings—sometimes even fetishizing the ‘real’, through dialogue and the depiction of violence—it remains rooted only in the cinematic reality of mainstream Bombay cinema: revolving around the story of two friends who are almost like brothers.

Amidst all the pre-release fanfare about Chakravyuh being an issue-based political film, an online comic series, launched by Jha to promote the film, forewarned of the action-cinema stereotypes Chakravyuh had fallen prey to. The film is strewn with such stereotypes found in a conventional Hindi film— honest cop, dedicated left wing activist, quintessential middle class rolling stone who switches loyalty, corrupt politician, greedy industrialist and exoticized tribal. In using these stereotypes, without any shades of grey, the film gives up on all nuances. Chakravyuh has good people and bad people on all sides but the good people are never bad and the bad people are never good. And so, despite seeming to have the intent of acquainting the masses with more than headlines, and tell them about what is going on in the heart of their country (even quite unexpectedly citing the Arjun Sengupta Committee Report in the final voiceover), Chakravyuh remains another film on ‘Friendship’, ‘Love’, ‘Duty’ and ‘Honour’.

Thin Red Line

ArticleNovember 2012

By Agnitra Ghosh

By Agnitra Ghosh

Agnitra Ghosh is a research scholar of Cinema Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Subjects he has worked on include cinephilia and Bombay cinema and film culture in the digital era. He is currently pursuing a PhD on the documentation of the Naxalbari Movement in Bengali Cinema. His other areas of interest are cinema and new technologies, film and history, cinephilia and art cinema.