Master Frames is a new series on the craft of cinema, in which we invite filmmakers, technicians and actors to deconstruct their processes for you. The people featured on this series are doing some of the most remarkable work happening in Indian cinema today and have a lot to offer to those who wish to learn from them or those who would simply like a backstage tour.

Here, filmmaker and screenwriter, Sujoy Ghosh talks about the making of his movies and his oeuvre.

Video Excerpts

ON DIRECTING AND MANAGING ACTORS

ON FINDING THE RIGHT STORY

ON FUNDING A FILM AND OTHER STRUGGLES

ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EDITING AND DIRECTION

ON SELF-CENSORSHIP

ON INVOLVEMENT WITH MARKETING AND PUBLICITY

How do you find your stories? Where do you find them? How do you know you’ve found something to make into a film?

Mostly, it all depends on what excites you, and what predominantly allows you to give your visual representation, in terms of a concept, right? So there are a lot of stories going around you, which you really can’t use. But if you find the story; like, three friends at different points in life, work in an office, play music by the night. But then how do you visually represent that? So once you have cracked that, when you have a story and you can pack the visual representation of the story and you’re equally excited after having cracked that, that’s when you find the story. You need to know whether you’re willing to give your whole life to make that story. Does it have something you really want to say? Something you want to take a stand on as a filmmaker?

Which brings me to the question of when you write stories. Is it the story first, and then the telling, or is your story written like a proto-screenplay? Or is it written like a novella that you then make into a screenplay?

Except Home Delivery (: Aapko… Ghar Tak), I think most of the time, I write a story first. It’s like a four pager that I write. So I know why my characters are… I know where they came from; I know where they’re going. For example, if Vidya (Balan) is working with me, I should be in a position to tell her that: Okay, right now she’s sitting in a police station… but where she was three days back or what she was doing an hour ago. So I should be able to know the whole universe of my story. The bits that I pick and choose to tell, that is different, that is selectively used in my screenplay.

So that’s a separate step for you?

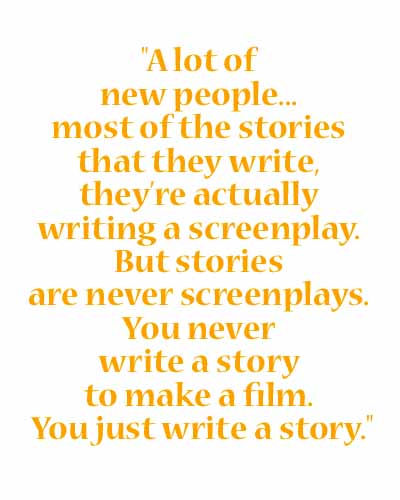

Absolutely. I see a lot of new people coming to me with stories; most of the stories that they write, they’re actually writing a screenplay. But stories are never screenplays. You never write a story to make a film. You just write a story. And then you take bits from the story, you add to the story, you delete from the story, you change the story, you mould it to whatever is needed in order to give you that visual representation.

Where have you learnt to write stories, where have you learnt how to tell them?

I keep my benchmark as my grandmother; my Dida was the best in terms of captivating my attention. I don’t know if it was my age, or whether it was my absolute zero knowledge of the environment around me. Whatever it was, I would like to be in that position, you know, where I am telling you a story and I totally have your attention.

But what about the story itself— the structure of the story etc. Where have you got those lessons from?

Yeah, I never had any formal training as such, but my biggest advantage was that when I was growing up I didn’t have anything like the internet. I just had books. So I read a lot. That was my only proper pastime, you know; whether I was in a toilet or in my room, or if I was eating, I always read. And, I think somewhere that probably helped me structure, in terms of the beginning, the middle and the end. Lot of people come to me and tell me all these fundamental things like Act 1, Act 2, Act 3, like fuck I know what they are! In a story, I try to see what it is that I’m seeking. What is it that’s exciting me? Whose story is it that I’m trying to tell. Once I’ve cracked that, then it’s quite an easy thing for me.

Do you still read a lot?

I try to. I don’t get that kind of time, but I try. I read a book, very recently, which was very nice, called Chanakya’s Chant (by Ashwin Sanghi). I also take a lot from graphic novels. It helps me to visualize, it helps me to tell a story in a manner which is more visual. I keep looking for things which help me represent emotions on screen.

So do you generally like writers who are also very visual?

I mean the last incredibly visual book that I had read was probably the first Harry Potter (and the Philosopher’s Stone) by (J. K.) Rowling. And the seventh one (Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows) too was visual; the seventh one was actually like a screenplay. Wait, the last such book was actually (The) Hunger Games (by Suzanne Collins), not Harry Potter…

You’ve often said you’ve learnt by watching films. Give me specifics of techniques you’ve learnt from films and filmmakers.

For example, I’ve learnt by watching (Alfred) Hitchcock, or reading Hitchcock, that food helps to calm you down. In the most intense moment, if you see food, food is a very natural thing to calm you down. So in Kahaani, you’ll see a lot of food. You feel comfortable when you’re seeing things which are very known, like Hakka noodles. So that really helps you. Then for example I wanted to establish the character of Vidya Bagchi as somebody who’s a little more exotic than what Rana has been seeing in terms of the women around him. Now he comes from a very average middle class family. He’s a mama’s boy. So he hasn’t really been exposed to too many women, right? So what we do is, from what I’ve learnt, you use a set up. You give him a computer, which he’s been struggling with. In comes Vidya, and in a matter of a seconds, helps him defeat the computer. And in the process, she becomes a heroine in Rana’s eyes. This is a technique (Satyajit) Ray used. The set up.

Also Sonny Corleone (in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather). He was the best set up in cinema. Why did they need three sons? Why couldn’t they have four sons, five sons or one son? It was a damn good set up because Sonny was the perfect heir to the empire. So Michael’s journey becomes so much more difficult for him, compared to Sonny, and then you start actually investing in Michael, which is the most predominant thing in the story. You need a hook. You need an investment.

What about pure technique, I mean, say something like a camera movement, or something like a shot or a framing?

My only framing reference till date has been a film called Mahanagar by Ray, which was filmed by Subrata Mitra.

What about the framing? The framing or the mise-en-scène?

The framing! Just the framing. I don’t believe in mise-en-scène or master shots or any of that rubbish.

When you say you don’t believe in all that, you mean you don’t look at your film through those…

No, I don’t understand them. Those terms are too by the book.

But mise-en-scène can be very simple also. It can just be what is in a frame. I mean if you look at the very basic of a mise-en-scène, it’s basically what is in your frame.

I guess, yeah. But you know, it’s like I remember in the beginning, I never believed in a master shot. Okay? But ADs (assistant directors) were always going on about master shots. But the problem is, the moment you take a master shot you give in to all those clichés: “master shot yeh-woh hai (whether a master shot is this or that)”. So I can’t think like that. I need to think as I work. Probably I’m wrong, because I‘ve gone wrong a couple of times…

But it’s interesting to me, because in Kahaani I felt like you were telling the story. The whole idea of mise-en-scène being that the frame tells the story, right? Your frame was telling the story as well, and I can’t believe it’s not conscious, you know?

Yeah, you know, it was… I just go with the flow. Like I never ever… how do I say it? It’s planned, but not to that extent.

So how do you determine your frame? Simply by the emotional or aesthetic need of the story, or also to add layers to it?

My frame is always about telling the story. My frame is always about the emotion in that moment. It is about what I really need to see. I used a lot of close-ups in Kahaani. I needed to stay with Vidya. Whereas in Aladin I didn’t mind a little wide shot because I wanted to show off my sets, how clever I am in creating this city. So it is more pertaining to the storytelling than anything else.

You have doffed your hat to the filmmakers you have learnt from in your films. Like the ‘running hot and cold water’ joke from (Ray’s) Joi Baba Felunath that you used in Kahaani. Can you remember other examples?

Aise bahut kuch tha! I mean, I have to now delve into the past… There were little references in Jhankaar (Beats), when that guy comes and says “I’ve seen hyenas in China” (from Ray’s Sonar Kella). So those are the little dialogues of Ray I have taken. So again in Jhankaar…when Rahul (Bose) just falls back on his bed, that’s my tribute to (Martin Scorsese’s) Mean Streets. But nobody will know. There’s a heavy background score, that’s Harvey Keitel falling. I mean, these are little things I do, but they’re too obscure to get…

Any books by directors that you recommend?

I’ve read of lot of Ray’s books like Our Films Their Films. It was a nice interpretation of things, in terms of analyzing cinema and everything. Not that I understood much of it. But it was a nice read. I like reading books by makers on how they made a film; the process they went through, the journey they went through, the small details.

Name three filmmakers whom you’d like to talk to about their process, other than Ray.

I’d love to… most of them are dead.

Yeah, that’s fine.

I would have loved to have a chat with Tapan Sinha. And who else? Probably (Steven) Spielberg, if I was given an opportunity, because I like the kind of stuff he does. And probably Rohit Shetty. I really want to know how he does that.

Where do you write? Do you have any writing rituals?

Recently, what’s happening is, I’m not getting the space to write because of my fucking mobile phone. If I do write, I like to go out a little. Even if I could lock myself in this room, I can get it done.

Do you have some amount of your story already concretely in your head, before you start putting it down on paper?

A lot of it, yes. At the back of my head. Like now I’m doing Badla. Badla has been there at the back of my head for a long time. And the thought keeps developing, little by little. Once I have a beginning and an end, you know, and a very vague journey. For example, the woman (in Kahaani) comes, she goes through things, lands up in Calcutta… the fact that she lands in Calcutta and not Bombay or Delhi, etc. Once I have sorted all that out, then I start writing.

Have you collaborated with any other writers on your scripts?

Yeah, only on Jhankaar… I didn’t collaborate with anybody.

What is the process like?

The process is I write a first draft. Then I bounce it off my standard army of writers and then they add their bits to it. And then we keep going back and forth until finally it takes a shape to which we say: “Yes, this is awesome,” or: “No, this is not happening.”

So you collaborate more on the story stage?

Yes, screenplay I do not collaborate on. I’m very selfish about screenplay. It’s what I bring to the table as the director. And it’s an incredibly enjoyable process for me, writing the screenplay.

Once the script is ready, how much feedback do you take on your script? Or when you’re writing it?

The way I work, I have some fulcrums on which I sort of structure my script. For example, most of the time—and it’s a very bad habit, so I wouldn’t recommend it—I have an actor in mind for certain roles. So these people, I bounce it off.

Why are you saying it’s a bad habit?

Because sometimes you can get stuck. Like if I write a script for one actor and they can’t do it.

But it’s a gamble. And if it pays off then does it make your script better?

It’s a gamble, yeah. If you can pull it off, nothing like it. But the film shouldn’t be for the actor. So when I have an idea that X actor will fit into a role, I go to that actor. Once my script is ready, say Kahaani, I ask Vidya: “What do you think?” If she likes it then I’m sorted. Then I keep the script as it is. Then all the improvisation, all the deletions, all the changes, I prefer them to be organic on the sets. Where, maybe, my DOP comes with suggestions and ADs come with suggestions or the actors or any of the technicians.

Asking for feedback at the script level can be tricky. Like I remember when I was doing Jhankaar… , that time Kaho Naa… (Pyaar Hai) had released and Hrithik (Roshan) was a phenomenon. So some people told me, why don’t you change R. D. Burman to Hrithik Roshan?

What?!

Yeah. You know, everybody has an opinion and I’m not going to sit here and waste my time arguing with you. So if you have an opinion, great, I’ll hear it. But I will only change something when it’s worth changing.

So there are no people outside the people you’re working with, to whom you narrate the story or your script to get feedback?

Earlier, no. But now I go to my aunt in Kolkata or get my mother to read. It’s very important because they are the audience. When I got my mother to read Kahaani, in the initial part she was a little confused, “Arey ki hochche (What’s happening?), I don’t understand this, or that.” And then I try to tweak it a little, not much, though I like this process.

Everything is critical in a film but every filmmaker has certain elements that are more critical to him than the others. How critical is dialogue to you?

It can be very critical. I’ll give you an example. Like this book I was telling you about, Chanakya’s Chant, that I just read. Now if I was to make that into a film, dialogues would be the most crucial part for me in that film. I would not even touch that film unless I know I am the world’s best dialogue writer for that film. Because language is central to that vision for me. The captivating stuff of dialogues.

Whereas, in a movie like Aladin, where I have other things to play with, in terms of the visuals and special effects, dialogues may not be that important. I can balance it off against my editing, against my background score, against gimmicks.

So you’re saying that it’s dictated by the film.

What I’m trying to say is, for me the battle is to captivate your attention and for winning that battle I have various means. I have dialogues, I have background score, I have my editing, I have my cinematography. So it’s what I use in what proportion. Like if I have a weak scene, I spice it up with a bit of background score, I try to camouflage it with some flashy editing.

Can you think of a scene from one of your movies which you feel, in retrospect, could have been made better if the dialogue was slightly better? And the flipside, a scene which you feel like the dialogue brings a lot to?

Yeah, I think the first 15 minutes of Home Delivery… , where I felt the dialogue should have been much crisper. You know what happens is… I think one of my biggest faults is that I write in English. Now the punch lines are in English— when you try to put them in Hindi, one line becomes four lines. And I think that’s where I probably went wrong, in terms of the dialogues of Home Delivery… because I was trying to Hindify in English. And as a process, some scenes dragged.

And the flipside?

My personal favourite, I think is, where Rana (in Kahaani) asks Nawaz (Nawazuddin Siddiqui), you know, “What is the difference between me and Milan Damji?” And he (Siddiqui) said: “There is no difference. We are for the law, he is against the law. That’s where we are right and he is wrong.” As a filmmaker I was really proud of that statement that I could make out there.

How do you name your characters?

That’s very difficult! This is probably the toughest part of writing, finding names. But I do a little bit of work. Like, for example, in Aladin, the word ‘genius’ came from the word genie. So we called Mr. (Amitabh) Bachchan Genius. And then we took the easy way out of calling Sanjay Dutt the Ringmaster because he looked like one. When I was doing Jhankaar… , the only name I thought of was Shanti. That name had a meaning in the whole movie. Apart from that I thought a bit about Shayan (Munshi)’s character, because I wanted a name which would sound both English and Hindi, so I called him Neel.

What about calling Vidya ‘Vidya’?

That actually was because of her own name, which is known as ‘Bidya Balone’ in Kolkata. Venkatesh came from a friend of mine, Soumya Venkateshan. And Soumya’s husband is called Arnab Basu. So I took her husband’s name too and put it in and Milan Damji came from the name of a hotel, some Damji. I remember seeing some Damji hotel when I used to go from Malad to Churchgate everyday. That’s where I got the surname and Milan was from Milan Luthria. Bob Biswas— I had a teacher in St. James (Ghosh’s school) called Mrs. Biswas and her husband was called Robert. Life is the best place to steal from.

But do you think it matters?

On hindsight it does. I try to give characters a name which somewhere shows a little bit of their character. Like when I wrote a script called Borivali, which had Mr. (Amitabh) Bachchan. His name was Pratap in that film because his character was like a ‘Pratap’. He was tall, he was arrogant, he had a lot of pent-up anger. So that name sort of fitted very well.

How do you name films?

I put in a lot of work on it. The name should define the film. It’s like a human being. A film, for me, is my child. So it’s like I have to give my child a name. So, that name will identify what the film is all about. So I put a lot of thought in the name. For me, a name is very important. I get the name of a film first. Like Badla, I waited to get that title for so long.

Was it hard to get the title? I’m assuming other people had registered Badla.

Yeah, it was very hard because people had the title and you have to wait till they let go of it before you can get it.

So why did you call Jhankaar Beats ‘Jhankaar Beats’?

The whole concept was about taking some old song, some boring melodious tune and adding a bit of spice to it. That’s what Jhankaar Beats was all about. Adding a bit of spice to your life. I got a huge amount of opposition to that name. You have no idea how people fought with me.

I can imagine.

That’s one thing I’m very grateful to Pakistan for, introducing Jhankaar Beats. First time I heard, it came from Pakistan, and I was blown.

It came from Pakistan? Really?!

Yeah.

And why is Kahaani called Kahaani ?

It was like they were playing chess with stories. She was telling a story, he was telling a story… The whole thing was a game of stories.

Okay, and why Home Delivery… ?

Home Delivery… because it’s about a man who has sort of deviated from his path, so it was like delivering a man back to his home.

Can you think of something you took from life and used to shape a character?

Most of my characters are from real life. For example, the whole concept of Juhi (Chawla) in Jhankaar… was created out of these keys my grandmother used to have at the end of her sari. Those keys signified her stature, those keys signified her standing and those keys signified some amount of unity. So my whole idea of Juhi’s character was those keys. I saw her as a woman who would have those keys, who would hold everything together. No matter what the calamity is, no matter what shit is going on, she would hold it together. And hence she was named Shanti also. Even Deep and Rishi, they’re also people I know, in Calcutta. I mean like, little things here and there. Rishi is like most of the people I meet. Like people who have become entrapped in their own doings. People who have to be funny all the time, even when they don’t want to be. But it’s the character they have built, they’re the funny guys, the clowns, so they have to keep cracking those one liners, you have no escape, because you’re your own monster. (Vidya) Balan’s character was totally based on my mother.

Can you think of something you might have borrowed from another film?

The image of Mr. (Amitabh) Bachchan and Raakhee (Gulzar) walking in the rain in Kaala Patthar has stayed in my head. It’s raining, there’s this Parikshit Sahni singing Jageya… And they are just walking and there’s no dialogue. That for me is the best love story ever, on screen. That somewhere is what you see between Rana and Vidya (in Kahaani). It’s all silent. It’s all about one lady just putting the lamps off and one man playing the mouth organ and watching her putting the lamps off. Those are very doomed love stories and they are awesome. Love in the truest sense. There’s no expectation in that relationship.

One more thing which probably stayed in my head is the character of Vijay in Deewaar. A man who would never step into a temple. But then he steps into a temple for his mother. That act has stayed with me. I think that’s probably what you see in Bishnu in Kahaani, when the kid gives the radio. I think that’s a great gesture, a selfless gesture.

Is there an image from real life that might have got stuck in your head, and might have found a way into your films?

Yeah. In Kolkata, during the (Durga) Puja what happens is, those four days you’re totally immersed in the pujo. Then the fourth day of the pujo totally fucks you up— when you realize it’s going to end. And, like you like your articles to end, I wanted Kahaani to end on a highly emotional note. And the only emotion that I could think of was the thought of Ma Durga going away. I’ve seen that. I’ve seen people crying. I’ve seen my elders breaking down and crying.

I get that because I’m from Calcutta, but were you afraid that it might not be universally relatable as a cultural experience?

Yes and no. For me that was the best representation and I took it straight out of my life. Somewhere I was confident that it would work because, at the end of the day, it evokes the mother. And ‘mother’ is universal. Like Mr. Manmohan Desai has taught us— ‘nothing in this world works better than a mother’. But it was a risk, you’re absolutely right.

How well should a director know his story before he starts shooting?

I personally need to know it inside out. I need to know every damn thing about every character of mine. That’s the only way I can work with my actors. I mean, if Nawaz says, “Why small Gold Flake?” I should be able to explain to him why I am asking him to carry a small packet of Gold Flake.

How do you do that? Do you write back stories?

The back stories are very important to me. It’s very important for me to know that Khan came up the hard way, that he was as simple as you and me, in terms of lifestyle. He worked his ass off, and had nobody to defend him. The only person he ever depended on was himself and hence the arrogance. Because whatever he’s done, he’s done it himself and he has a strong sense of loyalty. So the cigarette that he smoked back in the days, the cheapest cigarette that can be your best friend when you’re struggling, he still holds onto them and that loyalty is also reflected in the fact that he totally loves his country. So he says: “Fuck it! If I have to kill Vidya Bagchi, I will.”

How detailed are your back stories? Do your characters have birthdays?

Not yet. I know them from their childhood but that kind of detailing I haven’t done till now. Maybe in the future I will.

You were with Reuters once. Has journalism brought anything to your storytelling?

The whole Reuters process actually fucked me up. A wire service has a lot of responsibilities. Because based on what you are dispensing a lot of decisions are made. These are crucial decisions. There is a serious rigmarole, a procedure within Reuters wherein you have to verify everything. Facts were very important. Somewhere that stayed with me. When I do something I do tend to try to verify it as much as I can. I don’t take things on face value.

Give me an example.

Aladin, for example. When I created the world of Aladin, when I created Khwaish (a fictional city), I made sure that I did it by the book. So, in the absence of existing laws, I create for myself a set of laws like they do in journalism. Like we will not report bullshit. And I stuck to rules I made. So, in Aladin, the streets are cobbled, all the houses are heritage, so there’ll be no paint on any houses because heritage houses can’t have paint.

A belief in authenticity?

Yeah.

Do you write with an interval in mind?

Yes, I do. You have to.

The screenplay or the story?

A screenplay, not the story.

How do you feel about the interval as a filmmaker and as a writer?

I would be happy without an interval but then I’d prefer my film to be one and a half hour to one hour forty minutes. With an interval I do get the advantage of making my film up to two hours. I’ve grown up with intervals, so it’s sort of a part of my system and it doesn’t bother me.

Let’s talk about your team. You’ve said that you’ve chosen entirely new teams, other than your music directors, because you really wanted to be on your toes. I wanted to understand that a little better.

As a director, my main job is to manage people. I manage people. To bring out the best in people, whether it’s my DOP or whether it’s my editor. But if I’m doing it with the same people over and over again, then I don’t have any credibility. I should be able to do that with every team that I’ve been given. I should be able to do it with every new DOP. I should be able to do it with every new editor.

But didn’t that make it slightly more risky given that you’ve spoken about how Kahaani was do or die for you?

It’s risky! Yeah! I was going all out. So I thought, if I have to, let me go all out. I thought I was getting a little complacent. I could feel it. So I wanted to get out. I wanted to push myself into a little bit of an unsafe zone.

So, your film is only as good as your team or your film is only as good as you handle your team?

As I handle my team. I’m sorry, I’m not trying to bring it all back to myself. But the thing is, at the end of the day, you have to manage people. You have to maintain harmony.

What is your best quality as a director?

I can manage people very well.

What are some of things that you have or would like to change about yourself as a person, which you feel might make you a better filmmaker?

I really don’t know. I wish I knew. If I could crack that, I would be a better filmmaker tomorrow. I only keep learning with every film, and I’m quite happy about that because every film is a search, which is great fun.

What have you learnt on the job about directing actors?

Do not interfere. This is what I try to follow most of the time. When we make a film, it’s in blocks, in terms of scenes. Now each scene has a takeaway. Each scene has an emotional moment. Each requires an actor to act in a certain way, in order to convey that message to the audience. Like after this scene, the audience should know, the boy and girl have fallen in love, or they hate each other, or boy has stabbed the girl to death. So what I do is I tell them what I need, in terms of the take away, in terms of the emotion, and then I let them take it. Because I can’t tell them how to act, that’s what they bring to the table. What I can do is let them do it and I keep looking out for the emotion. And the minute it clicks, that’s the take.

So, if Vidya asks me, “I’m sitting on a chair in the police station. How I should be?” All I can tell her is that:“You’ve been travelling. You’re coming from London. You’ve been sitting on that economy class seat for the last 12 hours, in between, you probably took a break in Dubai. And in Dubai also you sat for 4 hours for a connecting flight, maybe you had a cup of tea, maybe you went to the loo. You probably got off at the airport there. The airport loos are very dirty, so you haven’t been to the loo. As a pregnant woman, you need to go the loo quite often. In the police station… like fuck if you’re going to the loo there.” So I give whatever I can, in terms of life, in terms of cueing them. Then it’s up to them. How much of it do they want to use. You remember that scene where Bob pushes her, right? And then he talks to her, she’s running and he’s talking to her. That scene wasn’t happening. So I told Bob (played by Saswata Chatterjee) that when we’re talking like this, it’s very comfortable, but if I come on your lap and start talking to you, and you don’t know me, you’d be very, very uncomfortable. Proximity is the key. So he keeps pushing her. He comes almost to her face, and that actually unnerves her. So it gives her a better cue. It helps her. We didn’t tell Vidya, that we’re going to do it. Like when Param (Parambrata Chatterjee) came in and Nawaz said, “Get the fuck out!” and all those expletives which he used, you should have seen Vidya’s face, which is absolutely in shock! And that’s a real take. Because she couldn’t believe that Nawaz could treat Param like that, because, she wasn’t told about that. So sometimes we employ these tricks and it’s great fun.

Have you ever suggested a quirk to actors? The one thing that stands out in your films is that you have a lot of interesting smaller characters.

I need to, because that’s how they stand out. I try to make them stand out. I try to write each character as a hero. Sometimes I succeed, sometimes I don’t. Like that stupid character we created (in Home Delivery… )called… that ‘Page 3 Psycho’, who had a wooden pen killing people. Stupid! But we did it. Then Mahima (Chaudhry, who plays Maya), in Home Delivery. We didn’t know what trait to give her. The only thing we could think of, is let her sari keep falling off…

Rana for example, is that Bengali boy thing who touches feet and he does pronaam. So those little things I tell them. And sometimes it works more organically, for example, that whole tram sequence. In Kahaani, that’s the sequence I was scared of the most because I was treading on very thin ice with that sequence.

You’re talking about the footsie.

Yes, the footsie sequence. I was shitting bricks with that sequence. I told Vidya but she insisted that: “No, let’s do it”. Rana (Parambrata Chatterjee) went along. It was a very organic thing we did. But it was important, because you have to make things a bit interesting. How long can you see a woman be morose and depressed.

You were scared because you thought you were stepping across the line?

Going over the line about the romance between them. I had a chance of being misinterpreted by the audience there. I was really insecure about that scene.

About Vidya’s character or their relationship?

Vidya’s character and subsequently the relationship. So I was a little iffy on that. And I didn’t know whether that scene was needed in that film. I have to also think of my audience, make sure I’m not confusing them. They should be on track. I shouldn’t be straying them to some other place.

But can you always control that? It’s about who understands certain subtleties and who doesn’t.

No, you absolutely cannot. The rest of the unit was absolutely confident. It was just me shitting bricks.

How much do you workshop and rehearse directors?

None. I just read scripts. Woh sab mein mujhe mazaa nahin aata (I don’t really enjoy doing all of that). I read the script with them once, or a couple of times.

Okay. Fair enough. What advice would you give to a first time filmmaker about pre-production?

I think it’s extremely important and I think that’s the process where you should spend the maximum time, as much as you can, given your budget, given your time. Because that’s the process in which you build the world in which you’re setting your film. And unless that world is believable, your movie won’t work.

How involved are you in the song making process? You’ve only worked with Vishal-Shekhar so far.

It kept changing with films. For example, in Jhankaar… , the songs were a part of the narrative. The songs actually helped me to take the story further. So that’s how I described it when Vishal (Dadlani) and Shekhar (Ravjiani) and I sat together. So they knew the situations, they knew what we had to say in that situation to further the story. And then you also work on the design of the song, in terms of, if you think within the song where Juhi (Chawla) is going to come, and she’s going to find the girl Shayan (Munshi) is in love with and we are going to establish how Juhi is a really nice character; even when she’s pregnant she gives her seat to somebody else. That designing we have to do.

With the music?

With the music. For example, in Home Delivery we know this kid is trying to sing to impress her brother. She doesn’t get it right. So that works very well in terms of a song which plays as a narrative within your film. Kahaani, however, was a different beast. That is an album complementary to the film. It wasn’t necessarily in the film but if you hear the album, it will reflect the sentiment, it will echo the characters, it will take you on the same journey which Vidya is taking in the film. And that’s what I told them I need, and then they created the songs on their own, to which I said yes or no. So Kahaani was a more independent process for them.

And how would you give feedback to them?

I tell them it’s not working. Do another one. Don’t be lazy.

That’s it?

Yeah.

And they’re fine with that?

Yeah. They’ll go and do another one. Because, you know, as a director or a father or a husband, or a son, or a brother, or whatever, one of my main jobs is to make decisions. And a lot of times I make my decisions based on gut. I have to. I don’t always have the requisite information around me to take an informed and educated call. My gut is all I have got. So when I see Nawaz and I think this could be Khan (the character he plays in Kahaani), I go with it. I could have gone wrong and I could have gone right.

What about background score? How well do you know what you want in your sound design?

Oh, very well! Fucking well! I’m crystal clear on that.

Is it a part of your screenplay?

No. It’s what I decide after I’ve shot my film. See, because a lot of things change. On a screenplay you can have a basic meter. Obviously when I give my script to the sound guys to read, they see: Okay this scene is set during Durga Puja, so we have the basic dhaak sound etc. But then when I’m editing, I’m getting to do my film again. So it is with my sound design. Even my colour correction. So every step I’m given a chance to make my film. And I utilize all these chances as well as I can.

So, you approach it more as layers. Separate layers that you add to. What is the ideal relationship between a filmmaker and an editor?

Stay the fuck away!

Really?

Yeah. They know their work. That’s why you are employing these people. You need to trust your people. You need to trust your army.

So you stay away in phase one…

I stay away in phase one. Let them make the film. They might interpret it in a totally different way. It might be better than what I have written.

How much brief do you give them before just letting them be?

They have the script. I don’t talk to them. They have a script.

What have you learnt in the process of editing four films?

Wastage.

Okay?

In terms of how not to waste footage. On my first day of Jhankaar… I had no clue what I was doing. I didn’t know when I should be calling cut, because everything was nice and fine. They were acting well and I thought why should I cut the damn thing. Let it go. Finish the full movie in one take kind of a thing. But then I realized the need for editing. So I went and bought a book. Somebody told me you have to call ‘cut’. I needed to understand why should I call a cut, at what point should I call a cut. And what is this cut? So I went and I bought a book. And I learnt about editing and I learnt how and why people edit. So now I know how to shoot.

From an editor’s point of view? And is that something you do?

I do. But I never impose that on my editor. I can easily shoot a film in a manner in which you will have no option but to join it like I want to join it. I would want the editor to join it. Because if you shoot it in a particular way you have no option because this bit can only come after this bit. But we don’t do that.

Do you shoot in sequence?

In terms of… what sequence?

In terms of scenes like the first scene, then the second one, like that…

No you don’t have the luxury. It’s very hard because of locations and everything. So if you go to a location you have to finish off all the sequences. The only time I had that flexibility was in Home Delivery, where the whole thing was set in a house. So I could actually do it scene-wise.

Did that help?

I think it somewhere helps the character. It helps the character in terms of the actors and it helps the continuity. Otherwise it is not a must. I am not too fussy about it.

When you see the first cut your editor makes, what do you expect? Your vision plus something?

Yes, they have to take it a notch higher. Otherwise there’s no point having an editor. They have to give me all the emotions that have been transcribed in the script. And if they’ve done it in a manner that’s engrossing, I’m good with it. I may suggest a change sometimes, like Kahaani, I had the biggest fight with (editor) Namrata (Rao) over expressions. In one scene Kharajda (Kharaj Mukherjee, playing a police inspector) questions her (Vidya) about firewalls. So she says that firewalls protect the computer. And he says like how the police protect the society. And she gives a very… a tired smile. Now Namrata was totally against it. She said that why should she smile at this point. Her thought process is: I need to get my husband. Why would she smile? My thought process was— she was trying to ease this police officer. So somewhere she’s being a little politically correct. So if this man has made a joke, it becomes mandatory for her to just smile at that joke. So those kind of things we have little fights over, otherwise we move on. But it’s great, as it helps you to see the character. Gives you an insight into the character.

In one of your interviews you said that your biggest learning from Kahaani has been that the story is paramount. Explain that?

Did I say that? Because for me, as a director, I don’t bring a story to the table. I bring the storytelling to the table. I invest in pre-production, in detailing characters, in giving my actors and technicians a better understanding of the world of the film. Even the dubbing process is important. For example, in Kahaani, when Rana is saying things to Mrs. Bagchi, he may be saying one thing, but in his head he may be thinking something else, because he’s working for Khan. So that has to come out in his dialogue. Then a lot of things get added at the screenplay level. For example, Bishnu never existed. Bob never existed to a certain extent in that format in the story. What I’m trying to say is, let me just articulate myself, Aladin probably didn’t work, not because of the story, but because of how I told the story.

What about the storytelling didn’t work in Aladin?

I think I failed to get people to believe in the world that I was creating. That world of ‘Khwaish’, was probably too alien for people. Of course, I can’t really take a call, on behalf of the audience, as to what was wrong. All I know is, I tried to say something and I failed to say it.

Home Delivery, Jhankaar Beats and Kahaani are all intimate, character driven films. Is that your comfort zone?

Yeah.

And can you leave the comfort zone?

Very easily. If I’m attracted to a story, I’ll move out of my comfort zone.

Is there any kind of film you feel you won’t be able to make?

I will not make any film that I can’t run away from. For example, I saw this film The Whistleblower. If I had made The Whistleblower I would have never made a movie again because I don’t know how to delve into a subject like that, understand it, and then just walk away from it. I would not be able to walk away.

When you look back at your films, do they also reflect what phase of life you were in when you made them?

When I look back, yes. But that wasn’t the intention. I don’t think I would have been able to handle Kahaani, when I was making Jhankaar… , in terms of understanding the characters. It doesn’t necessarily reflect what I was going through at that point of time but what I saw around me, yes. When I was thinking of Kahaani, I saw love had changed hugely as a concept, in terms of how the youth today understands it, from what it was when I was making Jhankaar... And that is something I wanted to explore. Today’s kids will accept a younger man falling in love with an older, pregnant woman more easily. It isn’t a radical idea for them.

You’re saying love has changed, or the moral codes have changed?

I think acceptance has changed, in terms of the various forms of love. There are no boundaries like sex (only) post marriage, (no) living-in etc. For example, when I was doing Home Delivery, I wanted to show a live-in relationship. In the film Vivek (Oberoi)’s character is living in with Ayesha (Takia)’s character. At the time I did that I believed it would be accepted. Earlier that would not have been the case. She would have been seen as a slut. But now all these thoughts are changing. I mean I’ll be stupid to stick to those norms which existed once, you know. I have to keep changing with the thoughts of what my audience is… of what I think at least, of what they are.

So your film is not about your thoughts or ideas on love at that point.

No, it’s not. I may believe in something totally different about love. See, somewhere the film is also a product. I have to sell it. As much as possible, I would like to make my product palatable to your taste as an audience, because I serve you. So if you come to my house, because I love double egg chicken roll, I’m not going to force you to have it. I crave good reviews. I crave awards. So I do pick things that are palatable to the audience. I do cheat.

Okay, so let me put it this way. How far would you stray from something you strongly believe in for commercial reasons, in a film?

Enough to convince myself that I can pull it off, that I can tell the story with conviction. It all depends on the script. I suppose it would differ from issue to issue, from subject to subject. I remember I was offered a huge amount of money to direct an ad for TV. The concept was that this man, who is trying to get his daughter married off, suddenly he sees this TV showcase. He buys the TV, gives it to the family of this prospective groom, and the daughter gets married. I wanted to slap the… My blood was boiling when I read this. How can you even allow scripts like this? So, I can only react violently, or however I react, once I have the idea in front of me. Then there are certain things I absolutely do not believe in. For example, you can offer me anything— I’m never going to do an ad for a fairness cream.

How involved are you in marketing and publicity?

Before I used to think I know about it. Now, I just don’t get into it. Because I think there are a set of people who are very well equipped, informed and very capable of handling that side of the business. The best thing is, unless and until they are totally projecting your product in a wrong manner, you should let them do it. I learnt this from Kahaani, actually. What happens is, when you make a film and once it’s ready, you are eager to show it as soon as possible. But the fact is, in Bengali we have this word called ‘sthankaalpatro’—there is the time, the people, the place—and they are all factors. You have to release it at the right time, in order to get the maximum possible advantage out of that product. With Kahaani what they did was, they waited for The Dirty Picture to release, which actually gave us a huge amount of boost. And then they released it after that. So it actually worked. Whereas I was thinking— why, why, why is The Dirty Picture getting the benefit of Vidya’s previous releases: No One Killed Jessica, Paa and Ishqiya. She had goodwill at that point and I wanted that goodwill for myself. They asked me to calm down. You know, that is the first rule of filmmaking— calm the fuck down. That’s all you need to do.

Do you cut your own trailers?

No. I don’t know how to. I try to shoot a couple of scenes which will help in making the trailer. But placing those scenes, whether the scenes can be placed in the trailer, I leave it to them. Cutting a trailer is a very specific and specialized job. Maybe there are directors who can cut a very good trailer. I know Sanjay Gupta cuts the most awesome trailers ever. He can take anything and make it look good. This time, I tried something different with Kahaani which actually worked. I give them the script at the same time as I gave it to everybody else on the team. I told them to think over it and let me know if they wanted me to shoot something in particular for the trailer. A trailer is my trick to get you into the hall, so I don’t care. It is a place where you can really cheat and con and do all kinds of horrible manipulations.

Have you found yourself self-censoring due to the fear of either state censorship or ‘hurting people’s sentiments’?

At times I have succumbed. In Kahaani, for example, there were a lot of cuss words. Basically, lots of fucks and bhenchods and all that. And we took it out, because we realized that even if it does add a little bit of tanginess to Nawaz’s character it’s not really doing anything. So we took it out. And it worked equally well. However, in Jhankaar… Jhankaar… was an adult film. Did you know that?

No.

Jhankaar… was an adult film, because it had the first ever blowjob in Hindi cinema. So we were having this meeting with the Censor Board and they said “If you take out those 12 frames, you get a U certificate”. I’m really proud of my producer, Pritish Nandy, because he let me keep those frames. I really didn’t want to cut them. Because that, for me, defined the film, that blowjob. It defined those characters. So it was a choice of 12 frames or an A certificate. An A certificate means you limit your audience. There are other commercial impacts too. But we took an A. So sometimes I have given in but sometimes I didn’t.

Can you think of one or two “Aha!” moments you’ve had about directing? It either comes in the form of acting or a visual. Any. But it has to be while filming, not after.

For example, in Kahaani when Bishnu gives the radio to Vidya, I knew the moment I saw the boy’s smile that I had my scene. Even till the giving of the radio I wasn’t sure of the scene. But the moment he smiled on camera, I was like dead fucking certain I had the scene. That scene was very crucial for me. I needed to get it right because without it the sequence was feeling incomplete.

What about moments that fulfill you, not just as a director but also personally?

The last shot of Kahaani. You have no idea how tough that was to shoot. To get the angle right, to get the floating of the idol right. But when I was watching it on screen it was hugely satisfying. I had got it. I knew it.

Can you think of really bad moments while filming?

Bad moments never happen while filming for me. I’m sure things have… you know, everything is bad probably in hindsight. But at that point of time, I don’t have the luxury to sit and analyze if anything does go wrong. It’s a part and parcel of life. I love my work… wake up happy. If I didn’t wake up happy, I would never go to work.

You enjoy yourself too much?

Yeah, yeah,yeah.

Final question on directing, there’s one concept of being the master of your film and then there is the idea of leaving the door open for organic possibilities. Have you figured out ways to strike a balance between the two?

That’s the deepest question I’ve ever faced. I don’t know, that’s my honest answer to this whole thing because… I really don’t have an answer to that.

Tell us about the struggles you’ve faced to raise money for your films. You said in an interview that you were ‘jugaadoo’ in that respect. How did you mean?

I did not mean it like it was carried in that interview. Raising money is the brass tacks of filmmaking. You have to convince someone to part with it. Now if you were the one with the money, and if I came to you saying, “Look, I have two flops behind me. I want to make a film with a pregnant woman; a thriller. The movie costs 16 crores on paper but I can make it for one third that price.” There’s a huge chance you won’t believe me. It was harder for me to sell Kahaani, whereas it was easier for me to sell a Home Delivery because Jhankaar Beats was a success. So it all depends on the baggage you’re carrying at thatpoint. Similarly, after Home Delivery, Aladin was a big challenge. It was a very expensive project butthankfully what has happened till date is I’ve always had the support of the actors. And that hugelyhelps in our industry.

You turned producer with Aladin?

Home Delivery...

Out of necessity or choice?

Necessity. I have done everything out of necessity— directing, producing… everything, except writing.

You became a director out of necessity?

Yeah, because nobody was ready to direct Jhankaar…

Has becoming a producer made you a better filmmaker, or is it an obstacle in the creative process?

I think producing has helped me to respect other people’s money. As a director, you do tend to get carried away— your needs, your greed, and rightfully so. As a director you would always want the best for your film. But as a producer, I can curtail those thoughts in my head. But what really helps, being a producer and a director, is when I write, I can write to satisfy the producer and the director without compromising. I would know, for example, if I’m writing a scene, and if it needs a bit of VFX, I can cut it down, in terms of writing it. Or I can write a complicated scene and use VFX to make that scene easier to shoot.

Is there a disadvantage as well?

Maybe somewhere in your head you do compromise. I don’t know.

How did you approach casting Calcutta as one of the characters in your film?

People get very “Aah! Kolkata!” when they watch Kahaani and rightfully so because it predominates the film. The thing is, when normally people shoot in Calcutta, usually there is no more than 5 minutes of it in a film. Now, why do people know Bombay so well? Because the movies that are set in Bombay introduce you to the people of Bombay. For me, if you want to know a city, you need to know its people. For that you need time and I had two hours to do this. I could show you the city in terms of the people who make it what it is, which in totality gives you a very good feel of Kolkata. I did not want to just fleetingly shoot the iconic images which help you to establish that this is Kolkata and leave it at that.

What is your personal relationship with Calcutta like?

For me, it’s a very secure piece of land. I can go in there and it’s my security blanket. My Calcutta is predominantly people… and I think, maybe, in hindsight, when you’re asking me about this, it could be that I left Calcutta when I was in Class 10 and at that time everything was very romantic. You know, people were beautiful, life was beautiful, you were in love and life was trouble-free. Probably I didn’t get to see the complicated side of Kolkata which I may have seen if I had stayed on longer. So it is that Calcutta that stays with me.

It gets more complicated when you try to work there.

Correct, you’re absolutely right. I never thought of it like that. But now that you say it… when I left Calcutta, I had a very romantic image of the city. And when I go back now I probably still live in that image.

What is the Calcutta of your mind like?

My Kolkata is still, you know, every evening, there is a shankh that sounds three times, people do pronaam. That is my Kolkata. I had a huge fight with all the reporters in Kolkata. “No! That is a very clichéd Kolkata,” they said. But that is my Kolkata. For me Kolkata is also food, huge amounts of food. Kolkata is chilly chicken for me. Nobody in the world makes chilly chicken like they do in Kolkata.

What are your places in Calcutta?

You really want to know? There’s a little rock in front of my house. That’s my place.

Where is your house?

Beltala road. I can sit there for days at a stretch. When we were in Kolkata, we used to regularly go to the temple. I don’t know why and we still do— to Kalighat. I still go to Vivekananda Park to have puchkas. And, all my bookshops, starting from Gariahat (road) to Bhowanipore to College Street.

Your parents had an unlikely and unusual marriage. What influences did they bring to your life?

Their marriage was proof to me that if you believe in something, you can do it. Even though my mother is a doctor and my father was a taxi driver, they were both quite similar. Both of them wanted just one thing of me— that I study. They used to just tell me this one thing— that we’re not going to be here forever. So I think that’s what really got my goat after a while. So that’s why I felt I had to study and make them happy. And I think somewhere because I saw them coming together, I saw them struggling, I saw them really working incredibly hard to give me a life, it sort of rooted me to a certain extent. I’ve seen a very hard side of life and then as I grew up I saw a very lavish side of life as well. I’ve come from living in a slum to living in England to making films.

A lot of filmmakers that you admire—in particular Ray—in several phases of his life have been intensely political in their films. Do you have a political consciousness when you’re making a film?

Zero.

I could tell. Why is that?

I’m not a political person from any angle. I don’t understand politics. I do not want to understand politics.

How many films do you watch? Do you watch a lot of films?

I do. I try to watch something every day. Initially it used to be a film a night. But now I watch a film and I watch a TV series. So that eats into my time.

What kind of films do you watch?

Anything. I’m not fussy about films in general, but it takes me a little bit of mental preparation to watch a black and white film. I can’t handle black and white films for some weird reason.

Who do you discuss films with the most?

You know, on Twitter, that’s the only place where I find people who actually respond with that enthusiasm.

See, I’m more of an audience than a filmmaker. I’ve been an audience a longer part of my life, and what happens now, I’ve realized, is that I’m not allowed to be an audience, like a sweet maker is not supposed to eat his sweets. I can’t be too vocal, for whatever reasons. I mean I can slice apart a Hollywood film but if I am critical about an Indian film I’ll get lynched or I’ll hurt sentiments which I don’t want to because at the end of the day, we’re all in the same family. But I do talk films with people like Sajid Khan and Sanjay Gupta who genuinely love films. If somebody knows films better than me it’s them. I can see you have a big smile on your face.

No, sure! I mean how you consume films can be entirely different from what films you make.

I can discuss films with them without getting too intense and analytical. Once someone, I can’t name the person, came up to me said, “Have you seen The Mirror?” And I really didn’t know what they were talking about. Some (Andrei) Tarkovsky film, as it turned out. And I thought he was talking about an actual mirror, and I generally on principle don’t have a mirror in my house. So we were both having totally different conversations.

Why don’t you have a mirror in your house?

I don’t believe in mirrors. They distract you.

Making movies or watching movies— which would be easier to give up?

Making movies.

You spoke about an image from a movie earlier; Amitabh Bachchan and Raakhee in Kaala Patthar walking together. Can you think of any other cinematic images that are lodged in your head?

I’m trying to think. One is a poster of Ganga Jamuna, where Dilip Kumar is screaming and Vyjayanthimala is dancing. The image of Jaya Bhaduri putting out that lamp in Sholay, and that one image in Mohabbatein where Shah Rukh (Khan) is just standing, holding his hand out and you don’t know why he’s holding his hand out.

One from your own film?

It’s from Kahaani. You’ll blink and you’ll miss it. This is where Vidya is crossing the street and she just steps back. You don’t see her face. It’s in the montage.

Okay.

Are you not going to ask me what it was like to work with Vidya Balan? Every interviewer asks me that.

Not yet. (Martin) Scorsese had said that there comes an age when (French film critic and theorist) Andre Bazin’s question—“What is cinema?”—becomes relevant and then it becomes irrelevant again. Is this question relevant today, to your generation of filmmakers?

I think that question is relevant at all points of time. I don’t know any deep or meaningful answers to this question but for me cinema is first of all, entertainment. It could also be a form of dispensing some kind of message to your audience, given the kind of maker you are, and what your take on society, the world, or individual things is. I think that changes from time to time. Also it changes with your audience. With time the audience becomes more accepting of different topics or different subjects or they travel more. Like when I was growing up, my mother was the only person I knew who had gone to England. Today everybody and their uncle and their uncle’s uncle have travelled much more than that. So your mind is expanding. Your acceptance is expanding. Cinema will keep changing to suit those tastes. At any given point, if you ask a maker ‘what is cinema?’ I’m sure he or she will have his/ her own interpretation of that.

What, according to you, is the most interesting about the era in which you’re making films, in India specifically?

The whole concept of the taste of audience—I don’t know if taste is the right word—but acceptance of various subjects. I love the fact that they’re exposed to much more now. So there are a lot of different stories that you can play with. There are a lot of forms that you can play with. The audience is willing to give you a chance.

Are you sure it’s that? There can be the classic chicken and egg argument about this. That the audience was always ready but there were no films being made to show that.

It could be that we have been using the audience as an excuse. In the past, films used to subscribe to some sort of success strategy or the other. But I think now, the appetite for taking risks is increasing, especially within the people who are financing films, which is the key thing. Because all this while, in our country, we never had any structured finance which was one of the reasons why films couldn’t get made. Films that used to get made, got stuck and never saw a release. But now, we are getting structured finance, we are getting people whose risk-taking appetite is larger and simultaneously we can present to them subjects which they believe the audience is more willing to accept.

So you’re saying that basically what matters is not whether the chicken came first or the egg, but what the people financing films believe.

To a certain extent, yes.

What is your biggest fear as a filmmaker?

Flops.

What is your biggest fear as a person?

I think if I lost the respect of my kids. That would be my biggest fear.

Okay, here goes, the question you don’t quite seem to like but anticipate nonetheless— what was it like to work with Vidya Balan?

Oh, fantastic! I’ve been looking forward to working with Vidya since I was that small. Finally got my chance and it was awesome— a sparkling moment. It was like one of those Happydent ads when she met me. Things lit up.

Is this an answer different from your usual answer?

Yeah, I never used Happydent before. I thought it was a good analogy. Thought I could sneak that in. I hope Happydent ads last as long as this interview did.

(video credits – Produced by Kavi Bhansali, Editing – Khushboo Agarwal Raj, Associate Editor – Chetan Motiwaras, Titles – Amrita Bagchi, Music Design – Naran Chandavarkar

Master Frames: Sujoy Ghosh

InterviewApril 2013

By Pragya Tiwari

By Pragya Tiwari

Pragya Tiwari is Editor-in-Chief at The Big Indian Picture.