Uday Bhatia traces the life and times of Neecha Nagar, the only Indian film to have won the highest award at the Cannes Film Festival, and Chetan Anand, the filmmaker behind this forgotten masterpiece

It’s easier to make a case for Chetan Anand as the Indian Orson Welles than it is for Neecha Nagar as our Citizen Kane. Like Welles, Anand came into filmmaking cold, but took to it like a natural. Both directors shared a predilection for darkly beautiful images, and an unwillingness to compromise, that earned them that lethal label— ‘difficult’. Yet, Welles’ debut is today considered one of the greatest movies ever made. Neecha Nagar (Lowly City), in spite of having been the only Indian film to have won the highest award at the Cannes Film Festival—the Grand Prix in 1946—remains little more than a trivia question in the land of its origin. Outside of academic circles, it is rarely discussed. Few have seen it, or know that it’s available on DVD. I found no mention of it during the recent festival organized in Delhi by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting to celebrate 100 years of Indian cinema.

Which begs the question: If this film is a cinematic treasure, as everyone from Satyajit Ray to Shekhar Kapur has attested, why has it been allowed to hide in plain sight?

A “little toy” called cinema

According to Ketan Anand, Chetan’s son, it was Hyatullah Ansari, founder of the Urdu daily Qaumi Awaz, who first thought of adapting Maxim Gorky’s The Lower Depths. This turn of the century play looked probingly at a bunch of characters in a decrepit lodging house, and derived much of its claustrophobic power by never moving the action outside of it. Neecha Nagar deviates from the original in this respect; its action alternating between Ooncha Nagar and the impoverished village it looks down upon (‘neecha’, or lowly, in every possible sense). Whether Anand, a fan of European and Russian cinema, ever saw Jean Renoir’s 1936 adaptation—which also flits between high and low society—is a matter of speculation.

In his autobiography, Balraj Sahni recalls the first time Anand mentioned his plans to direct a film. “You know, I am not at all keen on acting,” Anand told him. “What I want to do is to make a realistic and purposeful film. I have decided to call it Neecha Nagar. I shall show in it the economic struggle waged by the different classes of our society and I am not going to make any compromise with the box-office. In fact, right now, I am working on its scenario.”

This was Bombay, 1943. Both Sahni and Anand were members of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), then at the zenith of its influence. Early Indian cinema owes this leftist cultural organization an incalculable amount; poet and lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi, actor Prithviraj Kapoor, filmmaker Bimal Roy and film music composer Salil Chowdhury were all IPTA alumni. So was Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Neecha Nagar’s co-writer along with Ansari, a man with definite ideas about the revolutionary potential of cinema (in a letter to Mahatma Gandhi in 1939, he begged him to “give this little toy of ours, the cinema, which is not so useless as it looks, a little of your attention”). IPTA produced Neecha Nagar, as it did Abbas’ directorial debut Dharti Ke Lal.

Also, Anand wasn’t the only one debuting with Neecha Nagar. Kamini Kaushal, who plays the hero’s sister Rupa, had never appeared on screen before. Neither had Zohra Segal (seen here in a bit part) or the blandly handsome Rafiq Anwar, who plays Balraj, the college-educated leader of the villagers. Sitarist Ravi Shankar, who had recently joined IPTA, was drafted in by Anand even though he had never composed for a film before. And this would be the only film that Rafi Peer (superb as the villainous Sarkar) acted in, in Bombay; after Partition, he returned to Lahore and founded the prestigious Rafi Peer Theatre Workshop.

Inquilab Zindabad

In a fascinating interview given to the Centre of South Asian Studies in 1970, Abbas indicates a stream of insurrectionary moments in pre-1947 Indian cinema. He starts with Raja Harishchandra, the country’s first ever feature film, and proceeds to list a dozen odd titles which few today would have heard of, let alone seen; films like 1930’s Swaraj Toran (censored and released as Udaykal), 1931’s Bombs (released as Wrath) and 1936’s Jai Bharat. Neecha Nagar—which, oddly, Abbas fails to mention—falls squarely in this tradition.

Shooting for the film began in 1945, a year of great turmoil and nationalist fervour. Its plot is a simple enough allegory for British oppression (though it could apply equally well today as an illustration of official neglect). Sarkar, a smooth-talking industrialist, wants to construct a housing project on low-lying swampland. He conspires to drain the swamp and divert its waters, via an existing drain, to Neecha Nagar village. The villagers rise up against Sarkar, refusing his help even when disease and drought start taking their toll.

Seen today, the film is as blatant a jab at the British as was possible without it getting banned by the censors. It’s actually quite surprising that the makers got away with what they did: a brown sahib villain with a name like Sarkar; a hero who wears a Gandhi topi and advocates non-violent resistance; the boycott of Westernized goods (in this case a hospital) by the oppressed; and a goose bump inducing moment when dozens of torch-carrying protestors are shown to form a rough map of India. The British are never mentioned, but that’s hardly necessary.

Germano-Russian Extraction

Considering the number of cinematic traditions it draws on, Neecha Nagar would be ideal teaching material for a film class. First off, there’s the influence of German expressionist cinema. This isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. Early Indian cinema had very strong links with Germany. Himanshu Rai and Devika Rani trained at the German studio UFA. Franz Osten, who made his first film in Germany in 1911, was responsible for some of the best Indian silents, including Light of Asia (1925) and A Throw of Dice (1929). And what would Kamal Amrohi’s Mahal (1949) have been without Josef Wirsching’s fever dream photography?

While no German seems to have been directly associated with Neecha Nagar, cinematographer Bidyapati Ghosh was trained in Germany. His work in the film shows the clear influence of expressionism, a cinematic style pioneered by German directors like Robert Wiene and Fritz Lang. Expressionist films had odd, angular sets, bold angles and dramatic lighting— all of which are in evidence in Neecha Nagar. In addition, the idea of a half-crazed industrialist holding a disgruntled subterranean mob to ransom was at the heart of Lang’s 1927 classic Metropolis, as was the trope of the industrialist’s child falling in love with someone from the lower depths. Another nod to German cinema is the ever-present painting in Sarkar’s haveli, which shows a vampire-like individual standing in front of a bizarrely twisted landscape. It looks uncannily like an artist’s impression of Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari – a 1920 film credited with kicking off the expressionist movement.

For all its Germanic touches, one cannot ignore the influence of Soviet cinema on Neecha Nagar either.Take the example of the famous montage sequence that underlines the arrival of the drain water in the village. As Ravi Shankar’s sitar plucks out foreboding notes, the viewer is bombarded with a series of quick-fire images— emaciated cattle, sludge flowing downhill, dead birds, villagers trudging through the muck. One particularly memorable juxtaposition sees the head of a vulture replaced by that of Sarkar. As a stand-alone sequence, it’s as blatantly stirring as anything in Sergei Eisenstein’s films.

The Soviet influence on IPTA had always been strong. Krishan Chander, who co-wrote Abbas’ Dharti Ke Lal (1946), was a Russophile. Abbas himself co-directed the first Indo-Russian film production, Pardesi (1957). Balraj Sahni had fallen under the spell of Russian filmmakers like Vsevolod Pudovkin and Eisenstein during his time in London in the early 1940s. Anand too was a fan— after adapting Gorky in Neecha Nagar, he reworked Nikolai Gogol’s The Inspector General for his next film, Afsar (1950). He was also an admirer of Pudovkin, and is said to have invited him to stay at his Juhu home during the 1952 International Film Festival of India, in Bombay.

Besides the German and Russian cinematic traditions—which coalesce in spectacular fashion towards the end of the movie when vampiric static shots of Sarkar are intercut with images of a menacing gargoyle and the aforementioned painting—Neecha Nagar also makes use of homegrown devices, such as musical storytelling. The film has two dances, choreographed by Zohra Segal (and tacked on, post-Cannes, for the India release), and six songs. Not one of them, though, is a love song, romance being a possible casualty of Anand’s refusal to compromise with the box office.

Realism and Reality

It is tempting to try and detect the influence of Italian neorealist cinema on certain passages in Anand’s film. Yet, it’s unlikely that Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945)—the first widely known example of neorealism—reached India in time to be an influence. What can be stated with more surety is that Anand’s pioneering use of location shooting and frequently stark imagery make Neecha Nagar a landmark in Indo-realism (if such a genre exists), paving the way for Do Bigha Zamin (1953) and Pather Panchali (1955).

But if you’re the kind that believes reality trumps realism, that art imitates life, watch carefully around one hour and 12 minutes into the film. As the villagers stand beside a funeral pyre, a dog runs across the length of the screen. It’s seen in long shot, and barely for a second. Perhaps it was a detail added to increase authenticity; more likely, it was a mistake that survived the final edit because it was too difficult to cut out. Manny Farber once wrote about a scene from Howard Hawks’ The Big Sleep: “One of the fine moments in 1940’s film is no longer than a blink: (Humphrey) Bogart, as he crosses the street from one bookstore to another, looks up at a sign.” What impressed Farber was the way Bogie’s action allowed the viewer to believe, for one small moment, that the set and every fake prop in it was the real world. I feel the same way about this one-second canine cameo. I’d take it over all the montages in Russia.

A first at Cannes

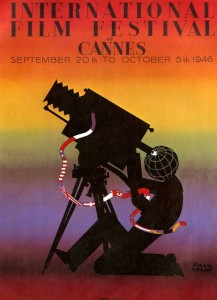

The first annual international film festival to come into being was Venice in 1932. By 1938, many felt the ruling Fascist party in Italy was exerting undue influence on the selection process. When Renoir’s The Grand Illusion was denied the top prize (then called the Mussolini Cup) in 1937, it riled up the French; when Leni Riefenstahl’s pro-Nazi documentary Olympia won the same award a year later, they shrugged and said “Je vous l’avais bien dit (I told you so).” On the train back from Venice, French government official Philippe Erlanger and film critic Rene Jeanne started hatching plans for a rival festival. Sunny Cannes, in France, was chosen as the venue, and an opening date of September 20, 1939 was set. But when Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, and kicked off World War II, the festival was shelved. It wasn’t until 1946, a year after the war had ended, that Cannes could finally open its doors to world cinema.

Does this story have anything to do with Neecha Nagar, beyond the fact that it won the top prize at Cannes that first year? It may. Eleven films were awarded the Grand Prix in 1946. Among these were The Lost Weekend, made by Billy Wilder, a Jew who’d fled Germany in 1934 and who worked briefly in Paris before starting on a remarkable Hollywood career; as well as Leopold Lindtberg’s The Last Chance, about an American and a Brit who escape Nazi prison. Yet another winner was Rome, Open City, Rossellini’s powerful anti-Fascist masterpiece. All this is to say that being seen as the anti-Venice was high on Cannes’ list of priorities in its inaugural year. Although its targets were imperialism and capitalism rather than fascism, Neecha Nagar may well have been advantaged by the pro-humanity, anti-oppression bent of the 1946 festival. Also, the idea of people revolting against their masters is always likely to find favour with the French.

“The tone is gloomy… ”

After Cannes, Anand may have been forgiven for feeling optimistic about his film’s chances at the box office back home. He should have, however, heeded Anton Chekhov’s warning about The Lower Depths. In a letter to Gorky dated July 29, 1902, Chekhov wrote: “The tone is gloomy, oppressive; the audience, unaccustomed to such subjects, will walk out of the theatre, and you may well say goodbye to your reputation as an optimist… ”

Neecha Nagar isn’t half as depressing as it would have been had it followed Gorky’s play faithfully (to see how that might have looked, watch Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 version with Toshiro Mifune). Yet, its commercial fortunes were blighted from the start. According to critic Jai Prakash Chouksey, it was only on Pandit Nehru’s insistence that the distributors released the film at all. But audiences didn’t care. Maybe they were put off by rumours that this was an ‘art film’. Perhaps they just didn’t feel like spending an edifying but miserable hour-and-forty-minutes watching this when they could be nodding along to K.L. Saigal. The easier-to-digest Dr. Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani was all the nationalism they could stomach that year. Neecha Nagar was a crashing failure.

There was more bad luck ahead for Anand. After Neecha Nagar failed at the box office, his directorial career stalled. It was only when younger brother Dev Anand found work as an actor that the brothers were able to launch Navketan Films. Even then, their first film together, Afsar, flopped. Aandhiyan followed in 1952— another disappointment. Finally, in 1954, Chetan managed a hit with the noirish Taxi Driver. Meanwhile, the negative of Neecha Nagar was lost in a fire, and the reel went missing. The latter was discovered years later in a Calcutta junk shop by Satyajit Ray’s cameraman Subrata Mitra, who bought it off the shopkeeper for Rs 100 and deposited it at the National Film Archives of India.

In the years that followed, Anand forged a fascinating, uneven and underappreciated career (there’s that Orson Welles connection again). His Haqeeqat (1964) was the granddaddy of Indian war movies— as well as a thank you to Nehru for his early support. Aakhri Khat (1966) saw him turn a 15-month-old toddler loose on the streets of Bombay and follow him with a handheld camera. Heer Raanjha was a 1970 film entirely in verse. But unlike his other sibling, director Vijay Anand, Chetan was never seen as a safe bet at the box office. In a 1960 letter published in Seminar, he complained to a friend about the many obstacles preventing him from making his film Anjali. One by one he ticks them off: financiers, distributors, government officials, even the audience. He ends on a poignant note, wondering aloud if he’s abetting his own downfall by naming his enemies in a letter. “I am often my own obstacle,” he concludes.

They say that everyone loves a hard luck story. By that yardstick, at least, both Chetan Anand and Neecha Nagar are unqualified successes.

Chetan Anand in his younger days (Courtesy S.M.M. Ausaja)

Trackbacks

RISEN FROM THE DEPTHS

ArticleMay 2013

By Uday Bhatia

By Uday Bhatia

Uday Bhatia is the Film Editor at Time Out Delhi. His writings have appeared in The Indian Express, GQ and Man's World. He thinks the world of Sachin Tendulkar and Lester Bangs, and denies charges of being reduced to tears by Remember the Titans

[…] the plot of India's sole Palm d'or winning social-realist film championing the underclass, 1946's Neecha Nagar.] It is upon this stage and this juncture in the wider narrative’s timeline that Boo steps in, […]