-

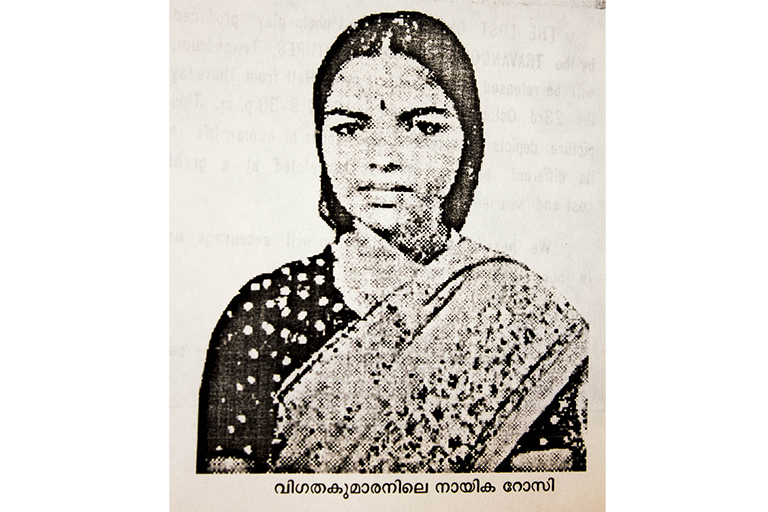

P. K. Rosy, Malayalam cinema's first actress

P. K. Rosy, Malayalam cinema's first actress -

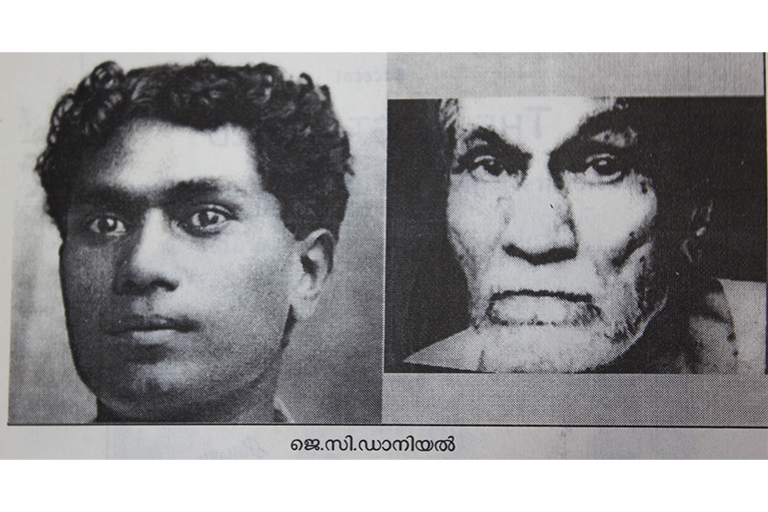

J. C. Daniel

J. C. Daniel -

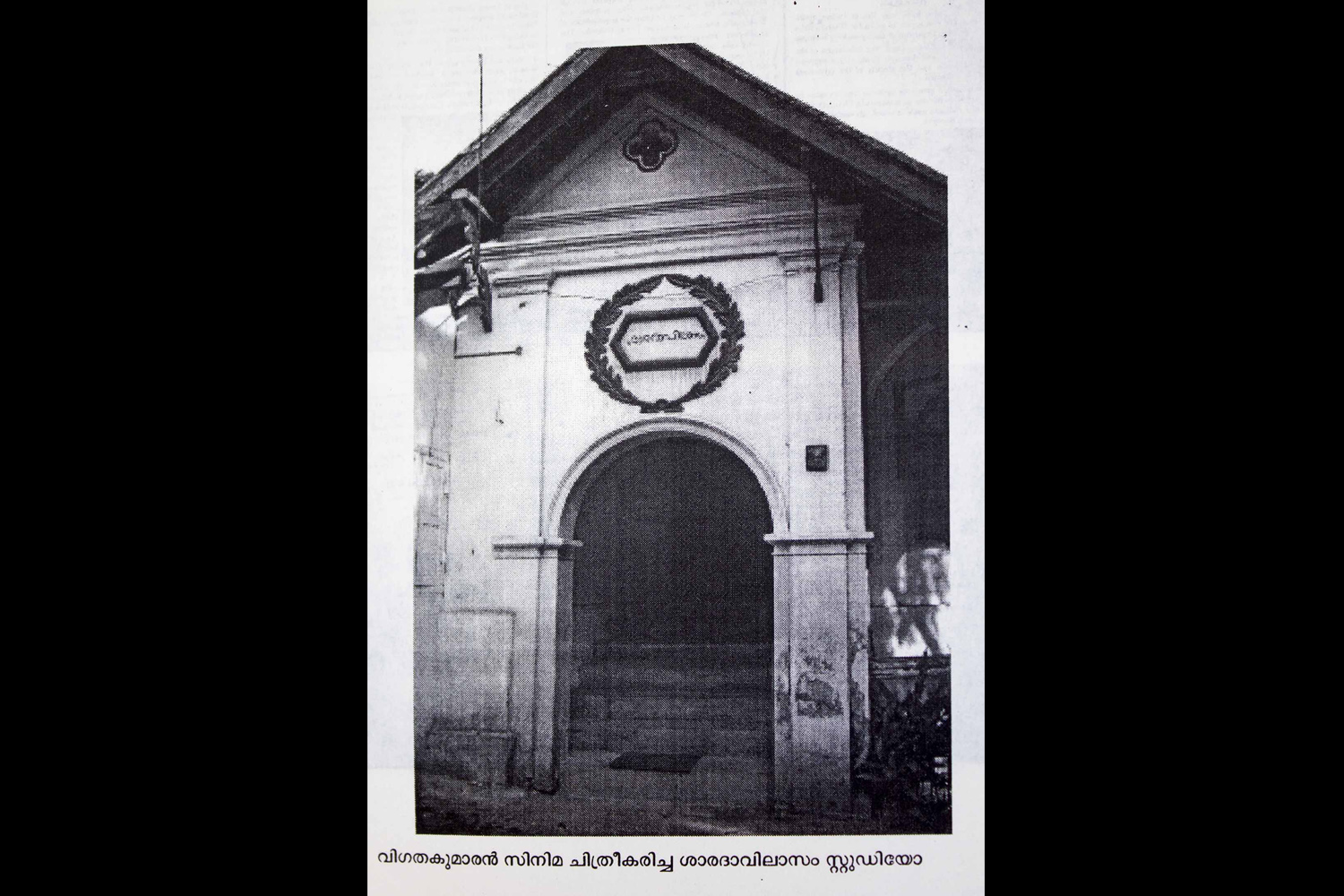

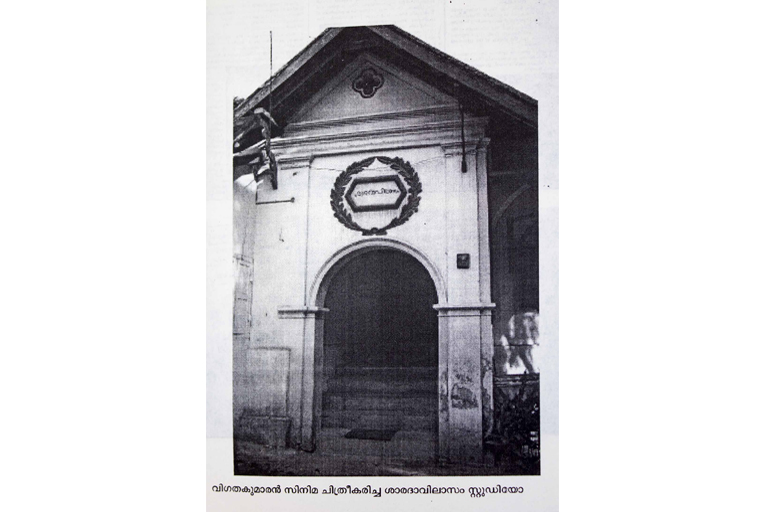

Sharadavilasam Studio, where Vigathakumaran was filmed.

Sharadavilasam Studio, where Vigathakumaran was filmed. -

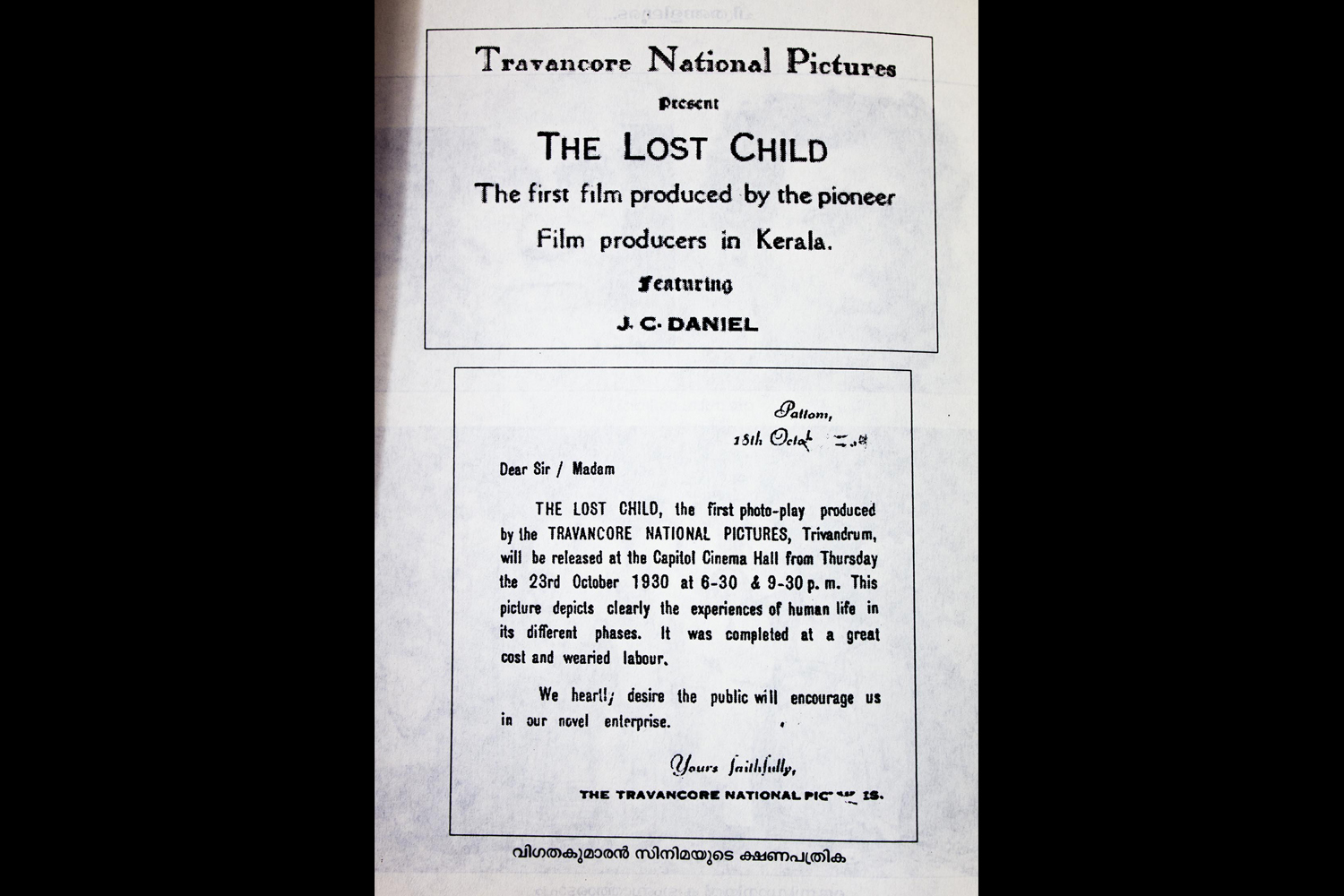

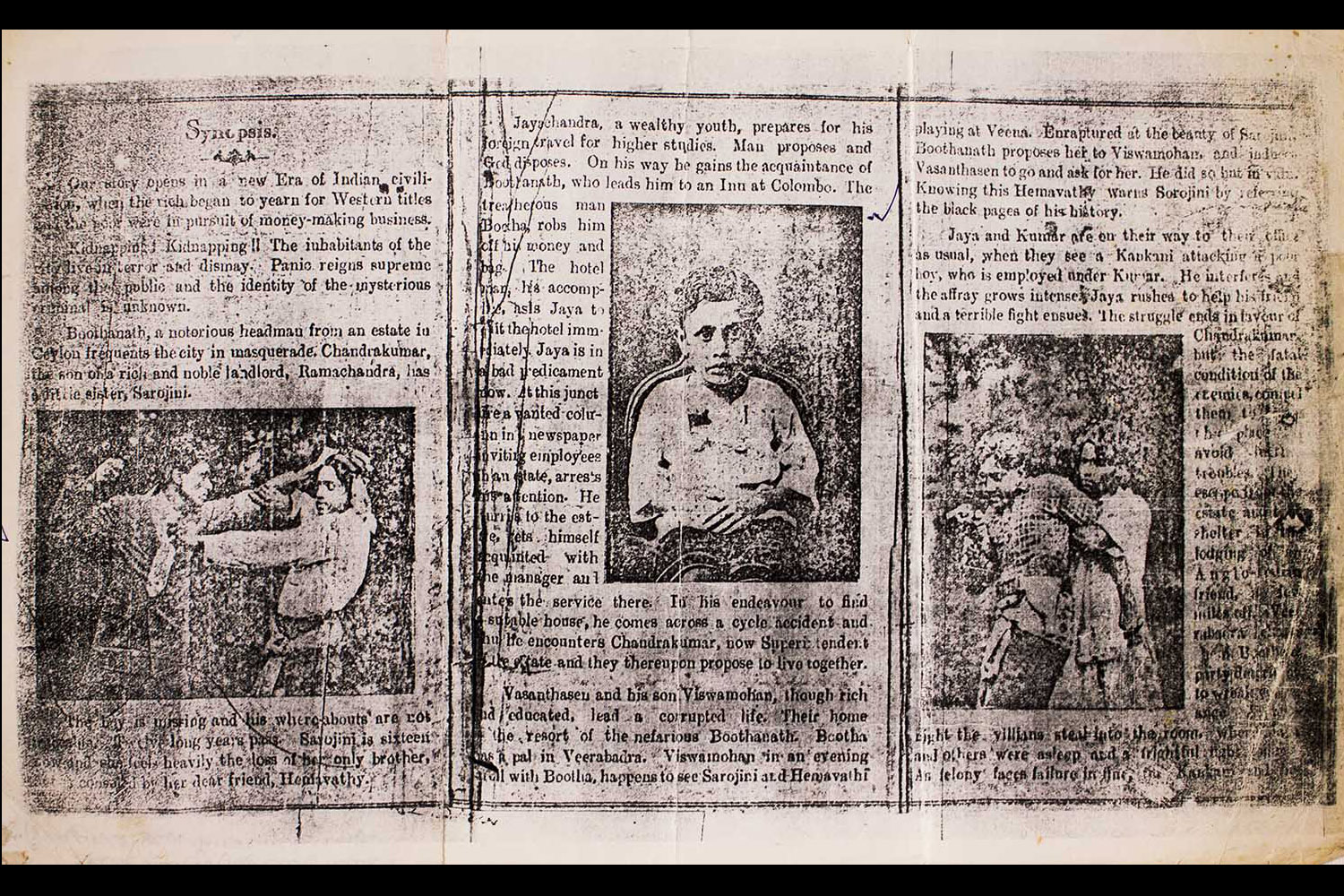

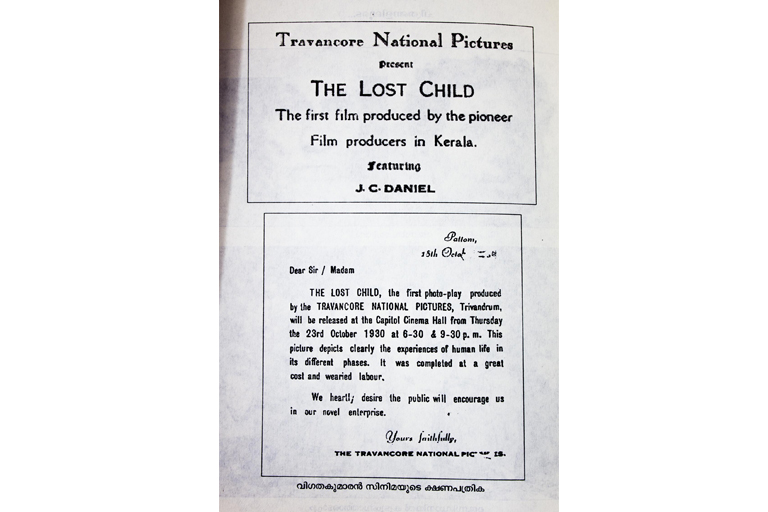

Invitation to the screening of Vigathakumaran.

Invitation to the screening of Vigathakumaran. -

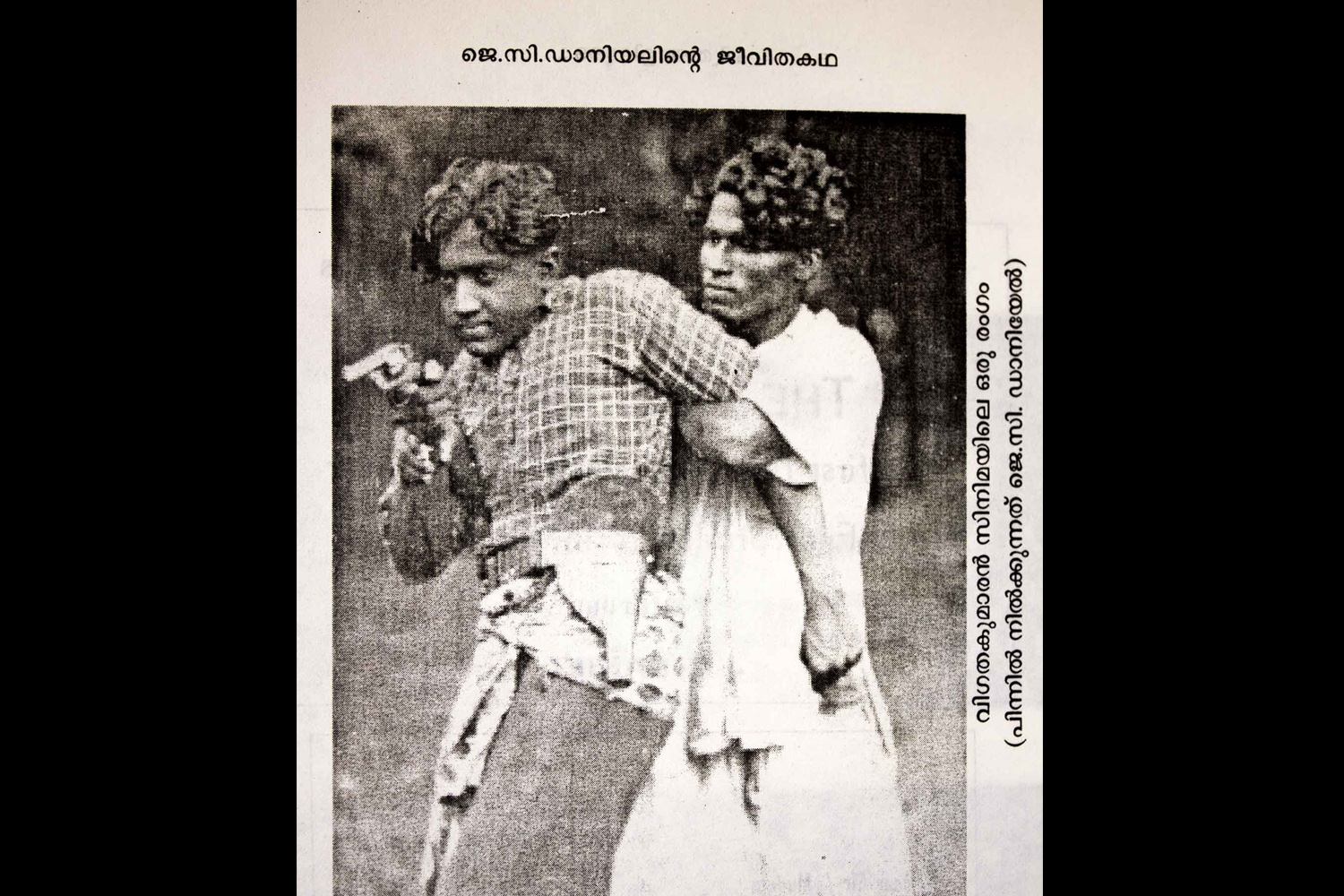

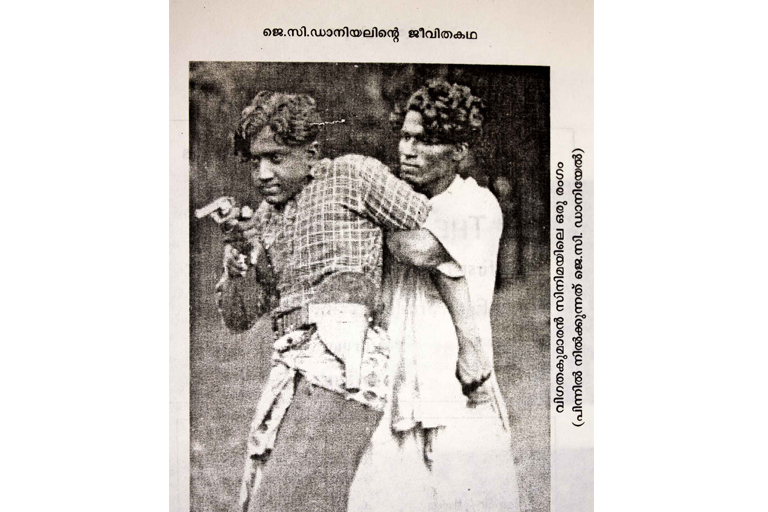

A still from Vigathakumaran

A still from Vigathakumaran -

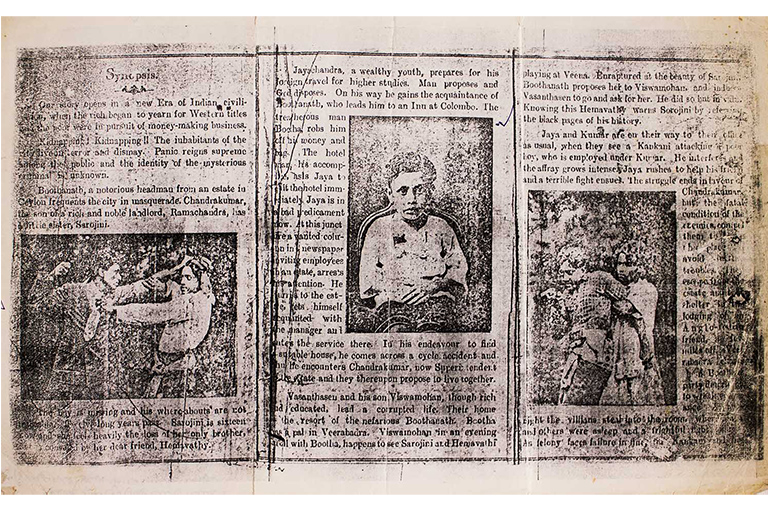

Synopsis of Vigathakumaran

Synopsis of Vigathakumaran

Everyone loves to tell the tragic tale of Rosy, Malayalam cinema’s first actress. In piecing together various narratives of her life, TBIP finds what is missing is her own voice.

When journalist Chellangatt Gopalakrishnan first wrote about Vigathakumaran, Malayalam cinema’s first film, all he knew about its leading lady was that her name was P. K. Rosy. Vigathakumaran, meaning ‘the lost child’, was first screened in 1928 at Thiruvanthapuram, Kerala. Gopalakrishnan’s first article on it is said to have appeared in 1968. In his subsequent investigation of the film, and the fate of its director J. C. Daniel, Gopalakrishnan did not find much else about Rosy save that she was “a poor woman who didn’t know the ABCs of acting,” and that she still “performed with great ease”.

The fact that Rosy, a Dalit woman, had portrayed a Nair—a higher caste—on screen had caused a furore among the pramanikal, the town’s elders, then. She was chased away from Thiruvananthapuram by a mob. With the help of a lorry driver, who later married her, she escaped to Nagercoil. The lorry driver happened to be a Nair. So, ironically, Rosy led the rest of her real life as the Nair woman she had dared to play, right up to her death in 1987.

In the years since she was first written about, in accounts of her life put forward by film historians, filmmakers and her relatives, other names for Rosy have emerged: Rajamma, Rosamma, Rajammal; each indicative of a period in her life.

Yet, despite several retellings of her story, the life of Kerala’s first actress remains shrouded in mystery. The controversies and debates raised by Celluloid, a recent Malayalam feature film directed by Kamal, based on the making of Vigathakumaran, has brought these discrepancies to light.

The Names

Another journalist, Kunnukuzhi Mani, has been credited with being the first person to try and dig out the truth about Rosy’s life, including, but not restricted to, her involvement in Vigathakumaran. “It was at N. N. Pillai’s theatre seminar in 1968 or 69, I think. Kambisseri Karunakaran (journalist, actor and politician belonging to the Communist Party of India) told me about Rosy, a poor woman, a grass-cutter, who acted in the first film. I started investigating from then. Kambisseri gave me the information. He asked if I would do an investigation on this. I was a reporter then, an editor for the paper Kalapremi.”

Kunnukuzhi met Rosy’s relatives and talked to them. He also spoke to J. C. Daniel’s relatives: “I went to Nagercoil. His siblings were there. I asked them about it. That’s how I found his house in Agastheeswaram (Tamil Nadu).”

After his conversation with Daniel, Kunnukuzhi came back and wrote his first article on Rosy in Kalapremi in 1971. Since then he has written about her in several Malayalam magazines such as Chithrabhumi, Chandrika, Tejas, Samakalina Masika.

Celluloid shows Rosy as a Dalit Christian woman named Rosamma. This is based on Gopalakrishnan’s description of her. But, according to Kunnukuzhi, Rosy’s real name was Rajamma. “When she came to work in the film, J. C. Daniel made it Rosy. And then (in Nagercoil) she changed it to Rajammal.”

On the basis of the information he collected, two documentaries on Rosy have been made— The Lost Child and Ithu Rosiyude Katha (This is Rosy’s Story).

Ithu Rosiyude Katha:

Early Years

Rosy was born into a Pulaya family in Peyad, Thiruvanathapuram, which was then a part of the princely state of Travancore. Her nephew Kavalur Madhu says her father passed away when she was very young. “When he died there was no one to look after them,” he says. “They were just two small kids and this woman (their mother). So we brought them to our house in Kavalur. This must have been between 1920 and 1925. Ours is a family of farm labourers. So they stayed with us.”

Her relatives remember her affinity towards the arts from when she was very young. In Kiran Ravindran’s documentary The Lost Child, Rosy’s cousin Madhavi recalls how fond she was of acting in plays, and how insistent on going for rehearsals at the kalari, the traditional training school for the performing arts.

“She had studied Kakkarashi (folk) dance drama when she was young,” says Madhu. “So she used to go to perform in these plays.” It was a time when, mostly, men played women’s roles. Acting was considered a profession for licentious women only. “So when she was asked, our grandfather did not allow for it. Those were the circumstances,” Madhu remembers. “But she went anyway, without the permission of our grandfather.”

She joined a drama company in Thycaud, Thiruvananthapuram, and stayed with them. According to Madhu, it is from here that Rosy went on to act in Daniel’s film.

What Happened That Night

In Celluloid, J. C. Daniel, played by Prithviraj, is shown having a difficult time getting an actress for his film. He finds Rosy, played by the young singer Chandni, when Johnson—the actor who plays the villain in Vigathakumaran—takes him to watch a play in which she is acting.

Rosy was cast opposite Daniel, who played the protagonist, in the role of the Nair woman Sarojini. According to an article written by Kavalur Krishnan (another nephew of Rosy’s) in Chithrabhumi (September, 2005), Daniel changed her name to Rosy “because the director felt that he didn’t want the name Rajamma but a (glamorous and anglicized) name like Ms. Lana, from Bombay (who was supposed to play Rosy’s role, but who had made too many demands that couldn’t be met).”

Krishnan adds: “But Rajamma didn’t know (when she was shooting for it) that the film would be shown to the public.” Rosy shot for the film for 10 days and was paid a daily a wage of Rs 5.

On November 7, 1928 Vigathakumaran was screened at Capitol Theatre at Thiruvananthapuram. Madhu says: “The film was released, and the pramanikal came to see it. Now, in south Travancore, it was a time when untouchability was practiced stringently. A person from a lower caste couldn’t even walk on the road at the same time when someone from a higher caste was on it. Those were the times in which she went to act in films.”

Celluloid shows Rosy being invited to see the film. “But Daniel had not invited her to see the film,” says Kunnukuzhi. “He himself said that to me. There would have been problems, because she was a Dalit woman, and so she had not been invited.” According to Madhu, despite not being invited, Rosy went to the screening with a friend. An eminent lawyer of the time, Malloor Govinda Pillai, had come to inaugurate the film. “He said that I will not inaugurate this film until she is removed from here,” says Madhu. “So Daniel asked her to watch the next show of the film instead.”

So, says Madhu, Rosy waited outside the theatre. “A Dalit woman acting as a Nair angered the pramanikal.” But what really sent the already disgruntled audience into an uproar was a scene that showed Daniel kissing the flower on Rosy’s hair. In outrage, they demolished the screen. “She was chased away (from the area),” Madhu says. She fled to Thycaud, and took refuge in the building of the drama company there, where she used to work. “The mob came to Thycaud to set fire to the building,” says Madhu. “And she had to run from there too.”

But Kunnukuzhi contradicts this version of the events. “There was a ruckus and they (the audience) destroyed the screen. A mob came to her house and began throwing stones at it. Then two policemen, whom Daniel had requested the Royal Court of Travancore to send, arrived on the scene. Eventually the mob dispersed. On the third night, after the film had opened, her house was set on fire. They had a house in Thycaud poremboke bhoomi (poremboke bhoomi means ‘unregistered wasteland’). When the house was set on fire all of them—the family members—managed to get out of the house and ran away from the area, to save themselves from the mob.”

Many years after the incident, when Kunnukuzhi spoke to Daniel, “all he knew was that she had escaped. He didn’t say much else.”

Whichever of these versions is true, Rosy had, after either sequence of events, run towards Karamana. “Near the Karamana bridge, it was quite late at night, she saw a lorry come by,” says Kunnukuzhi. “It was from the Paiyyar Company (a transport company from Nagercoil, now in Tamil Nadu, then also part of the princely state of Travancore). Kesava Pillai was the driver. She stood in the middle of the road, raised her arms and cried for help. So Pillai took her onto the lorry and they went back to Nagercoil (where the lorry had come from). That night she was presented before the Nagercoil Police Station and the incident was reported. Then he took her home.”

Keshava Pillai and Rosy got married. This, no one doubts. Accounts vary on whether or not Rosy was Pillai’s first wife. According to Kunnukuzhi, Pillai was not married when he met Rosy: “He was from a Nair household. He was kicked out because he married her.” Madhu, on the other hand, says that Rosy was Pillai’s second wife: “He had a wife and family in Neyyattinkara (now in Kerala), but he abandoned them.”

The couple moved to Otapura Theruvu in Vadasery, Nagercoil. Rosy adopted the name Rajammal. Ammal is a suffix that denotes respect, often attached to the names of women belonging to higher castes in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. The couple lived as Nairs.

The Debates

“There are a lot of mistakes in the film (Celluloid), even though it did get awards,” Kunnukuzhi says. “In those days, in Capitol theatre, there were no chairs. He (Kamal) shot it with chairs. I wrote about this in Mathrubhumi. In those days there were only ‘floor tickets’ (for seating on the floor). There was Bharathiamma, a native of Kuzhithura (in Kerala). She passed away recently. She has talked about this fact in Kiran Ravindran’s The Lost Child. She was 12 when she came with her father to Capitol theatre to watch the film. They watched it sitting on the floor.”

But the film’s portrayal of Rosy raises the question of whether or not she was ever called Rosamma. This fuels pre-existing speculations about her life— Was Rosy a Christian? Did she have a Christian stepfather?

Krishnan, another nephew of Rosy, claims to be the only one alive, besides her two surviving children, to have met Rosy in person and spoken to her. He vehemently denies that Rosy had ever converted to Christianity. “Her mother’s name was Kunji, father’s name— Naanan, older sister’s name— Chellamma, younger sister’s name— Sarojini. Her name was Rajamma and her brother’s name was Govindan. When you look at all that, how can you say she was Christian? Who said she was a Christian? We don’t know who said these things. My grandfather’s family has traditionally been Hindu, belonging to the Ayyankali Sabha (the Ayyankali Sabha had several Dalit communities. Rosy’s family was of the Pulaya community).”

Kunnukuzhi had long discussions on this with Kamal. He insists Rosy was never converted to Christianity. According to him, it was her father who was Christian. “To send Rosy to study, he converted to Christianity at the LMS Church. That was the basis on which children were given education in those days. No one else had converted. Her mother lived as a Hindu.”

Ravindran, who made The Lost Child, is not sure. “When her father converted to Christianity, his name became Paulose,” he says. “He may have changed her name to Rosamma. I don’t know about that well enough.”

Madhu on the other hand says that Rosy’s father had passed away when she was young and that it was Rosy’s stepfather who was Christian. “He was a cook for the Church priests. He is her stepfather, not the real one. That is how ‘Rosamma’ came to be. That is what Daniel took and changed to Rosy.” According to Madhu, the whole family had converted to Christianity, “but only for a short time (till the stepfather worked with the Church).”

Vinu Abraham, Celluloid’s screenplay writer, and the author of the book Nashtanayika from which the film has been inspired, says that his research found that Rosy’s family had converted. To explain this, he provides a sweeping generalization: “Because, in those days, the Pulaya community used to convert to Christianity.”

Madhu brushes aside these statements. “The people talking about it don’t know anything. Kunnukuzhi doesn’t know anything. They are from outside (of the family). We are the ones who know about it.”

Madhu then goes on to contradict himself by disagreeing with another family member as well: “My relative Kavalur Krishnan is the one telling Kunnukuzhi all this. And Kunnukuzhi must have told Vinu Abraham.”

Says Kunnukuzhi, about Madhu, “He is her relative. Yes. But it is only recently that he has come out into the open saying that he is her relative. I asked him about her several times but he didn’t know a thing.”

And so it goes on.

The Inheritance of Rosy’s ‘Shame’.

In the myriad narratives of Rosy’s story, the silence of her children is the most conspicuous.

No one can ascertain how much they actually know about their mother. “She didn’t talk about it with anyone. It is said that there was an agreement between husband and wife (not to talk about it),” says Kunnukuzhi. He says that Rosy had five children, three of whom have passed away. Her son Nagappan Pillai and her daughter Padmaja are alive. Kunnukuzhi spoke with Nagappan once. “He lives as a Nair, so doesn’t talk about this too much. I have talked with him on phone. Then he had agreed to everything. But now he won’t talk. Because he says it causes family problems.”

Madhu says that Rosy didn’t give her children too many details about her past. Also: “They do know what happened. But they don’t want to say that she was like this (a Dalit who was Malayalam cinema’s first leading actress).” Why? “Nagappan has married into a big Nair family from Alappuzha (Kerala). If he says that his mother was a Dalit, then the marriage would be in trouble. That is why he won’t talk about this. He doesn’t want to have anything to do with this. They (the children) grew up in different circumstances. They say: ‘Please leave us alone. Don’t involve us in any of this.’”

Vinu Abraham concurs: “In Nagercoil she could never reveal her real identity because she lived as a Nair. Her son doesn’t want to reveal that she was a Dalit, that a Dalit was his mother— he will never admit to that.”

Abraham says that when he asked Nagappan about Rosy all he had to say was: “I don’t know. I only know my mother was a Nair woman. That her name was Rosy, that she was a Pulaya lady, that she was an actress— all this I’m hearing from you. It is totally news to me.”

Yet, with the release of Celluloid, Nagappan is likely to be asked about Rosy again, many times. The secret shame of this Dalit who played an upper caste has been resuscitated, even after her death. Malayalam cinema’s first lady, a Pulaya driven to become a Nair, by a sequence of events that were set into motion by those who were enraged at her playing a Nair, has been resurrected on screen, 75 years after she had first appeared on it. And with this has been bared the scar of a wound that may have been inflicted long ago, but which refuses to disappear. Not with a change of name and caste. Not with the passage of time.

On Celluloid, again.

Kamal calls Celluloid a biopic that has been treated in places with fiction, “But I haven’t changed incidents or history. I have presented it as I know it. The portions of his (Daniel’s) life or Rosy’s life that we don’t know about— in such places I have fictionalized the account for the sake of the film.”

For Kamal, the film was about J. C. Daniel’s life. “The connection between Rosy and Daniel was over once the film’s shoot was complete,” he says. Also, the confusing details of Rosy’s story have stopped Kamal from delving deeper into it: “So we don’t know what the facts are. Maybe she didn’t want to tell people that she has acted in a film. I have taken what I can from history. I have never said that everything in the film is a real fact.”

Ajith Kumar A. S., a filmmaker and writer on Dalit issues, believes that Kamal’s excuse, about Rosy not being the main character of the film, does not hold because she is there for more than half of the film. “He has shown her, not just as an actress of the first Malayalam film but as a tragic character, treating her with extreme sympathy. She becomes representative of caste.”

Rosy’s submissive representation bothers Ajith: “She is shown as someone who feels that she doesn’t deserve anything. She is the only one shown bearing the burden of caste.” And Daniel becomes the uplifter. Ajith finds it particularly disturbing that the film looks at casteist issues as vices of the past and, in the same vein, conveniently casts Rosy in the mould of a tragic actress of the yesteryear.

Filmmaker Rupesh Kumar, another important voice on the Dalit discourse, agrees with Ajith: “Kamal in his cinematic text, through camera angles, through script representation, through directorial representation, through various cinematic techniques, effectively sidelines Rosy’s character.” An important question, according to Rupesh, would be how Kamal, as a male director, views Dalit femininity. “Considering the physical environment, the geographical environment and the working class atmosphere in which this Dalit woman lived, there is no way she would have been this submissive. That is my personal inference. If this cinematic text had been produced by a Dalit—male or female—her representation would have been very different.”

“I made it (Celluloid) the way I thought it would have been,” says Kamal. “It is not only Dalits who have the right to portray how she would have been. I did it from my point of view. If they object to that, it’s fine. I have nothing to say to that.”

***

In March this year, Director Devaprasad Narayanan has announced plans for another film on the life of P. K. Rosy.

Meanwhile, the commemoration of P. K. Rosy continues.

At the muhurtham (a ceremony held when the film went on the floor) of Celluloid, in September last year, Kerala’s Chief Minister Oommen Chandy said, “I have received a request to honour Malayalam film’s first actress Rosy by instating a film award and I am pleased to announce that the state government is all for it.”

The address by Jenny Rowena, Associate Professor at Miranda House, at the P. K. Rosy Memorial Lecture held in Jamia Millia Islamia, echoes the sentiments of Ajith and Rupesh Kumar. She said: “Mainstream discourses… enhance the progressiveness and castelessness of their present with this new and attractive museum piece called P. K. Rosy.” Rowena encouraged those present to understand the social context in which the harassment that Rosy faced arose— and to question whether anything has changed at all.

The debate and discussion that has emerged among filmmakers, academicians and writers, against the backdrop of Celluloid has propelled Rosy’s tragic personal story into becoming the nucleus of a larger sociological discussion that examines the interrelationship between caste, gender, society and cinema.

Cinema especially. That white screen on which ‘Rosy’ was projected, and which was torn down. Which made her an emblem for many things. Women’s rights. The caste struggle. And also, for cinema itself.

For films and film journalists and film historians have told and retold the story of Malayalam cinema’s first heroine in many voices, and many versions, which provide us with an array of narratives to choose from in order to reconstruct the life and times of Rosy.

Yet what continues to remain untold is Rosy’s story in her own words. The story she took with her to her grave. What stands out in the various reports, written and cinematic, on Rosy’s life, despite so many of these being produced before her death, is the absence of her voice, her version.

While the films on Rosy’s life were made after she had passed away, even the journalists who have researched and written about her—while she was alive—have never met their subject. More than three decades after Vigathakumaran released, Chellangatt Gopalakrishnan had gone looking for the place where Rosy’s house had stood. He had taken directions from J. C. Daniel. He found a hut near where her house had been. He spoke to the old couple in the hut. They said that they didn’t know what had become of her. He writes: “The old lady spat in hatred… ‘Must have died. What will you get from finding about that shameless woman?’ The woman got angry and went back into the hut.”

Even Kunnukuzhi, said to be the first person to know and write about Rosy, possibly the one who has researched and written on her the most, never met her in person. “At that time, there wasn’t much information on her or where she was,” he says. “It is only after the year 2000 that we came to know. We hadn’t known where in Tamil Nadu she was. I went four to five times and looked around in Nagercoil but couldn’t find her. We knew she had gone to Nagercoil but we got the complete details (of her address) very late.”

Kunnukuzhi found out finally from her nephew Krishnan, who had met her and stayed with her in Nagercoil. Kunnukuzhi, along with some others, had organized a memorial service for Rosy. “There was a seminar,” he says. “Krishnan came and spoke there and that is how the details started to come forth.”

Krishnan, not Rosy. For emblems do not speak. They are tired, and resigned.

The Name of the Rose

ArticleJune 2013

By Meryl Mary Sebastian

By Meryl Mary Sebastian

Meryl Mary Sebastian is Junior Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture