-

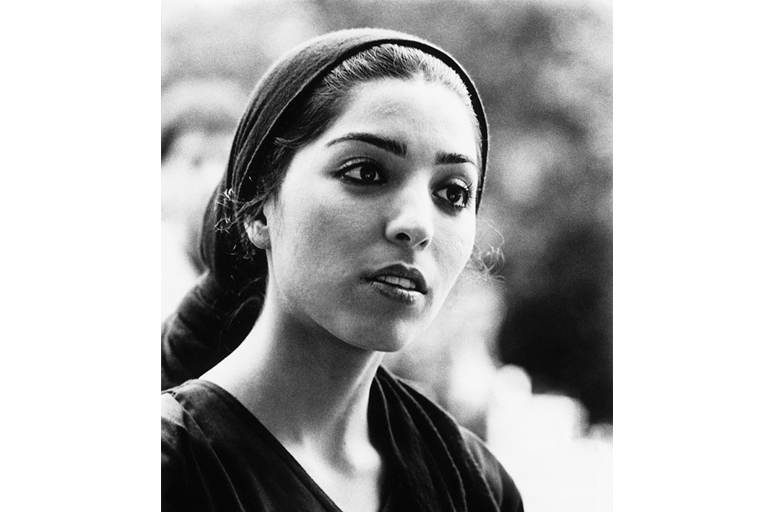

Samira Makhmalbaf

Samira Makhmalbaf -

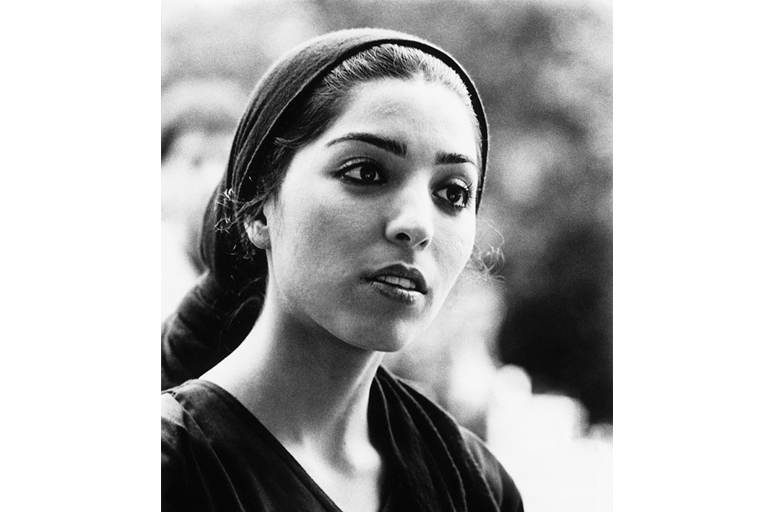

Samira in How Samira Made The Blackboard, directed by her brother Maysam

Samira in How Samira Made The Blackboard, directed by her brother Maysam -

Samira on the sets of her first film The Apple

Samira on the sets of her first film The Apple -

Samira Makhmalbaf

Samira Makhmalbaf -

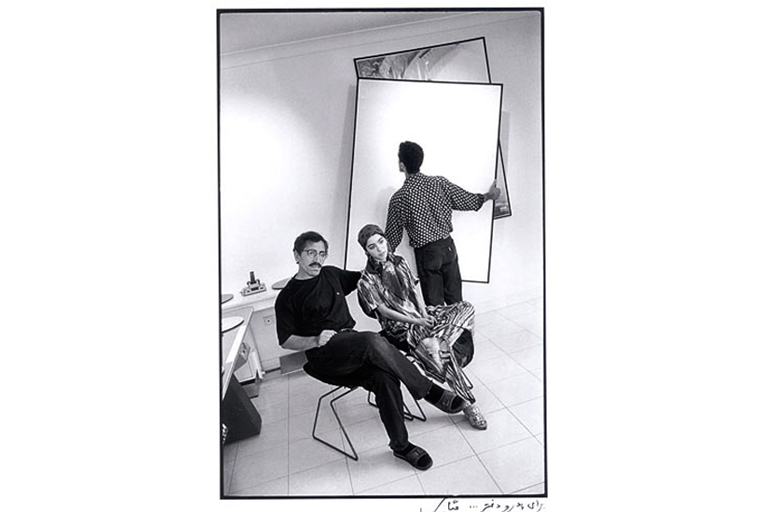

A young Samira on the sets of a film with her father Mohsen Makhmalbaf

A young Samira on the sets of a film with her father Mohsen Makhmalbaf -

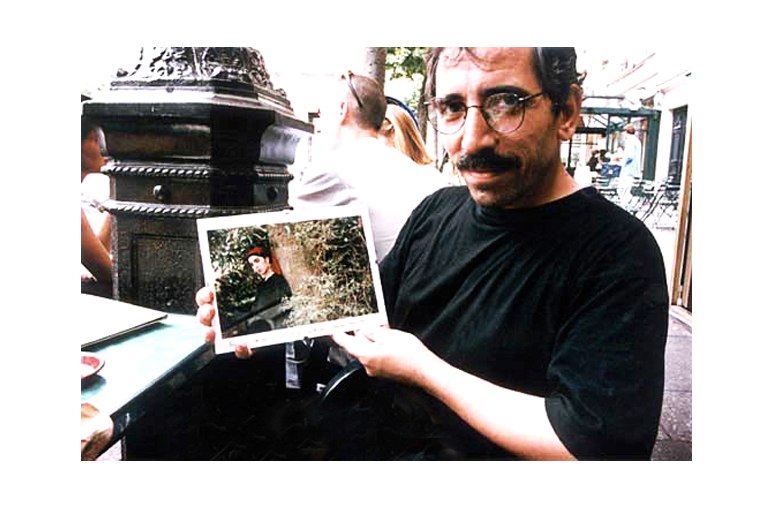

Mohsen Makhmalbaf proudly shows a still of Samira from a film

Mohsen Makhmalbaf proudly shows a still of Samira from a film

33 year old Samira Makhmalbaf, clad in black, sits on a plastic chair, patiently greeting many people who have lined up to talk to her. Someone hands her a canvas, a portrait of her in charcoal. She smiles. Her quiet, gentle demeanour belies the many laurels her work has won world over.

The eldest of the three Makhmalbaf siblings, Iranian director and screenwriter Samira is the first in her family to follow in the footsteps of her father, renowned filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Yet today she is a force to be reckoned with on her own steam.

At 17, she was the youngest director to present her feature film, ‘The Apple’, in the Un Certain Regard section at the Festival de Cannes. This was her first feature. Films that followed, ‘The Blackboard’ and ‘At Five in the Afternoon’, also competed at Cannes, winning the Jury Prize in 2000 and 2003 respectively. ‘At Five in the Afternoon’ was the first feature film shot in Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban. Samira has been a member of the Jury at Cannes too, as well as of that at the Venice International Film Festival, the Berlin International Film Festival, the Moscow International Film Festival, the Locarno Film Festival and the Montreal World Film Festival. She is said to be a part of the ‘New Wave’ of Iranian cinema.

What was it like to grow up around your father? To grow up acting in his films and working so closely with him, even when you worked on your own films? What influence has he had on your personal journey as a filmmaker? Do you consciously think about distinguishing your work from his when you make movies?

I can say the first thing that my father gave me was the love of cinema, because there are a lot of filmmakers in the world but I don’t think that all their children are making films, or that they love cinema this much, or that they ‘continue’ cinema (as a legacy). I love my father a lot, and I saw his passion for cinema, and I wanted to discover cinema. And I remember when I was five years old, when I saw his film screened on the big screen, for me it was like a miracle. It was the best thing I knew.

Which film was it?

It was The Peddler. For me it was this miracle and I wanted to do the same thing. Also his personality… I think even if he was not a filmmaker he would inspire me in many ways as a human being. It is possible to just watch him and gain. Watch him searching for peace, and making the world a better world. Because, I think, his cinema is not just about making films. Cinema is not, for him, just an entertainment. So I think I have learned that from him. Also, he became my teacher, because I left school at the age of 15 and then he taught cinema to me. And then, our relationship is actually like four relationships: he is my father, he is my teacher, he is my friend and he is my colleague. These are different roles. And I can say he has been my biggest teacher, for the longest time, and if I have some influence of his, I’m proud of that. But whether my cinema is different from his or not, all I can say is that I think that as human beings we are different in many aspects. I am Samira and he is Mohsen. But ultimately it is for the audience to gauge from watching my films.

You were the subject of your brother Maysam’s documentary (How Samira Made The Blackboard) and your sister Hana also initially started off (Joy of Madness) by shooting you casting for your film (At Five in the Afternoon). What was it like being on that side of the camera? Being the subject…

Actually I just kept doing my job. I was very focused on the making and I was not conscious about being shot myself, about How Samira Made The Blackboard. I was doing what I had to do. Because I don’t make films like a very professional person who treats filmmaking like an industry. For me, making a film is like a very big belief in what I do. It’s a very big passion. And I believe it’s going to change something for at least one person in the world. So, in that moment, even though it is hard or difficult, as making films is a challenge, I forget everything. I forget myself.

But what I remember about Hana’s film, which started with me casting for mine, but which is a completely different film… what I remember is that, once or twice, I was very aware of her filming me. Because, you see, this was the first time after the fall of the Taliban, in Afghanistan. I was making a film there and women were not ready for that and they were scared of it— so you were very aware of what was happening around you. And you can see the real face of Afghanistan through my sister’s film because she was very young, just 14 years old, and her camera was not something very special. So sometimes they didn’t notice her and sometimes they would be surprised at how she didn’t listen to me. And thank god she didn’t listen to me (when I suggested to her that it may not be a good idea) and she made this film.

How Samira Made The Black Board is from when I was 18. I was in the festival with my first film The Apple and it was a big question for people. They always asked me, “Oh! You are a woman. You come from Iran. You are young.” You know, sometimes they said, “You are small. How can you make a film?” Very quickly after that, it came to my mind, “Okay. A filmmaker should be an old, big man, even European.” I wanted to make the film The Apple but it so happened that I became a symbol of women, young women, who can make films. And once you’ve made a film then you break this cliché and after that it’s easier. Because then people can think that, “Okay, if one can do that, others can do it as well.” And I think for my brother also it was something interesting to look at in my filmmaking, and to see how the process of it is. So, for that, he made the film.

How Samira Made The Blackboard:

The Apple:

At Five in the Afternoon:

It’s interesting that you say that, because the kind of films you make are very political. Their themes are very political. So when you make such films, do you feel as if a political role has been thrust upon you? You may not think of yourself as a spokesperson in any way but do you feel that people, especially Iranians, expect you to represent them in a particular way?

I feel my films of course have some political dimension and layer as well, because of living in Iran. Because politics is interfering with our lives in every single moment. If we want to think of something, the politicians and rules have to decide. They decide whether we can make this film or not— especially in Iran. Also they try and decide what we believe or, on some days, what we eat or what we drink, to whom we talk to… and all these things. So it is a case of politics interfering in our life. So when we talk about a human story, it also becomes political. And, of course, as a filmmaker, one can talk about every subject one wants to talk about. But for me, the first important thing is not politics, it’s human issues. Because, I think, if we take a relationship between two humans, and if we focus on that—say the relationship between two friends, or a husband and wife—if we focus on that and if it’s correct, if it’s good, if it’s humanistic and if there is peace in there, then it becomes peaceful and good in the larger view of things. So if we don’t find democracy at a place you will not find democracy even in the human relationships there. So they ask me, “You are Iranian? You are a woman?” I think before being a woman, Iranian, young, old, being born at this moment, or later or before, I’m a human. So I try to tell the story of that. The main subjects of my films are human issues. Of course, they’re talking about one’s culture as well, and they’re also talking about politics.

Besides the content of your films, is there a politics to your aesthetics, your form, as well?

Of course. It’s an art, but I believe beauty and art can save the world. I’m an artist and, for me, creating art and beautiful things is one of the first things I care about. How to tell a story, how to picture scenes myself, how are the songs and the music of the film… I think a film is two things: what you want to say, and how you tell that. Both are important. I don’t think they’re very different. Content and form come together. The rhythm of a film is the film itself. The way you talk about it is exactly what you say. And, as I told you, my films are humanistic and also political. They are not just political. Of course, I also talk about the relationship between concepts such as ‘power’ and ‘the nation’. But where does power come from? From human relationships.

You use non-actors in your films. Do you do so to bring about a certain sense of realism?

Yes, I always work with non-professional actors in the films and I love it. I make films about real people. My inspiration comes from reality. So I want real people in the films. It’s difficult but if you can be patient and if you know what to do, it can be a miracle and magic. Because their reality and their imagination also come into the film. Their soul also, their story also, comes into the film.

How difficult is it, because they are not actors?

It is difficult and it is challenging but if you know what you need, then the result is great. And I have to say there are some techniques I use. It takes a lot of trust and faith and love. When I search for my actors I search for someone whose soul is similar to the soul of my character and then I don’t tell them the whole story. I just give them the general idea, but I don’t let them know every detail of what is happening.

Do they read the script?

No, I just tell them the general idea. And many times the whole script is actually written only after editing because something or the other changes while making the film. As they (the actors) come into the film, their reality, their real life or some part of their person, affects the film. Sometimes I explain things to them, sometimes I try to make them imitate me and sometimes I evoke something in them because I know that if I tell him or her a particular thing then he or she is going to show that character. So these are the things I do.

You mix real stories and fiction, which emerges from your imagination, in your films. How do you balance the two?

About imagination and reality? I think that, for me, art is where reality and imagination make love together and there is this miracle that happens where you can’t tell what is real and what is imagined, where are the metaphors and where you are speaking directly. People see themselves in the film, but it doesn’t end there. It’s like in surrealism. I like the surrealism not of (Salvador) Dali, which is completely imagination, but (Rene) Magritte’s surrealism, in which there is some reality and at the same time there are one or two elements that are not real and you don’t know where the border between the two lies. Here is the window, you see that it’s real. But in the picture, in the painting, where the clouds come in, there is a little bit of surrealism, which I like. And this imagination comes from the first idea and also from the imagination of the character as well.

How do you think films are going to bring about change in Iran? Because you make films, your whole family makes films, but there is strict censorship within the country and your films are banned— so people can’t see them. So how do you think films can bring about a change? Can they at all?

I’ll answer this generally, not only about Iran. Humans in the world are suffering from lots of pain and much of it is because of the way we think. And cinema has the power to change the way we think and that is one of the reasons I am in cinema. And, also, I think cinema is like a mirror; you put in front of society and society and culture can see itself and if they find something wrong they can change it. So yes, I believe cinema can change the world for the better.

Do you think people in Iran are aware of the significance their cinema has across the world?

I think so, yes. And, especially, I can see that through my father’s films because it was after the (Islamic) Revolution, because he was thinking of the progress after the Revolution and everything. And artists are most sensitive to these changes. They think and they bring up what is happening in society. If there is pain, they feel that. If there is some beauty, they see that. Especially after the Revolution, we have good art cinema because of many reasons. Because of not having Hollywood in Iran and also because of censorship which puts a lot of pressures on filmmakers and artists. In another way it makes them stronger to search for what they want to say through cinema. To search themselves and our culture. So they (the filmmakers) went to poetry. And I think when there is some darkness, sometimes, you can find light and if you can find the light in the darkness that is very important.

“I want real people in the films.”

InterviewAugust 2013

By Meryl Mary Sebastian

By Meryl Mary Sebastian

Meryl Mary Sebastian is Junior Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture