-

A still from The Insider

A still from The Insider -

A still from His Girl Friday

A still from His Girl Friday -

A still from Citizen Kane

A still from Citizen Kane -

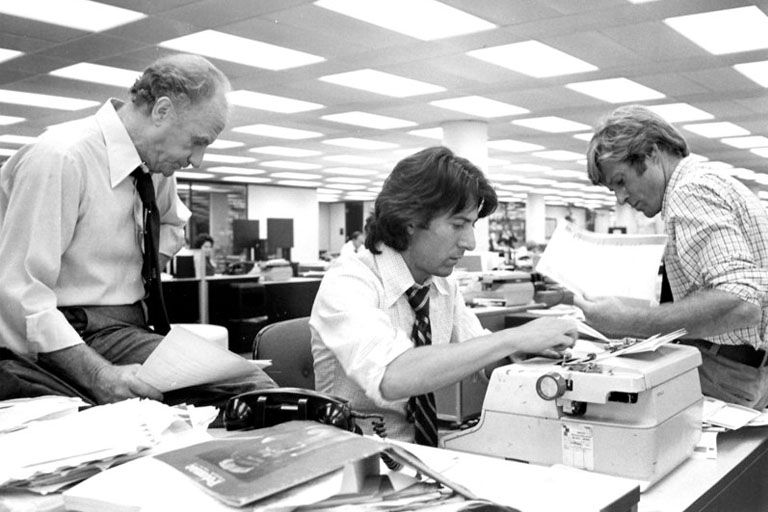

A still from All The President's Men

A still from All The President's Men -

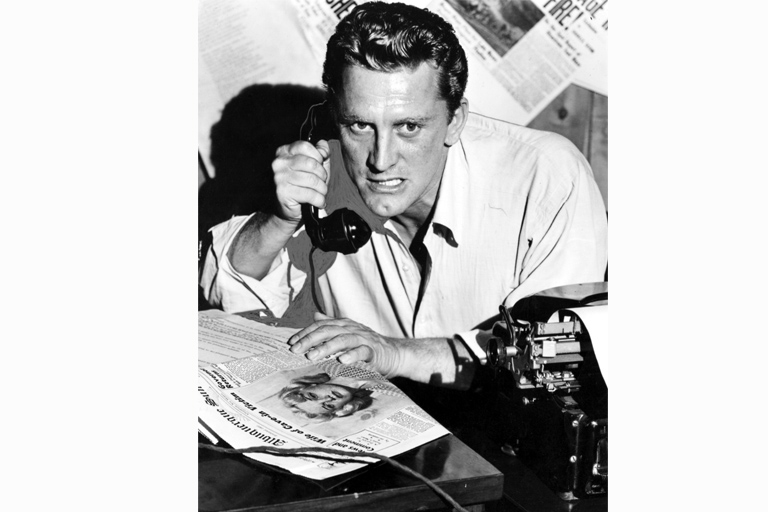

A still from Ace In The Hole

A still from Ace In The Hole -

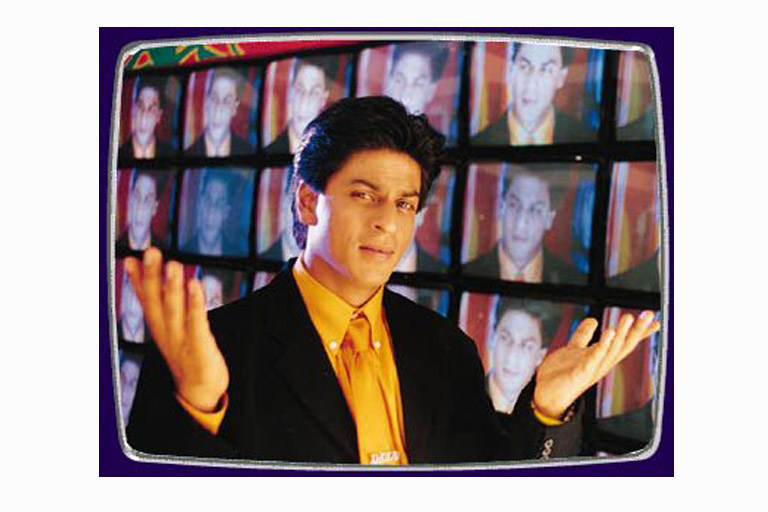

A still from Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani

A still from Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani -

A still from Peepli Live

A still from Peepli Live

Vijay Simha has been a journalist for two decades. Here, he tells you about seven journalism movies you must watch and why.

Anyone who’s been in a newsroom would tell you that you need to be crazy to want to be a journalist. It doesn’t get the big bucks in— especially not in India even though it is the world’s biggest media hub. Nor does journalism provide the sort of stability that might enable one to plan a regular urban middle-class life— with ample occasion for dinner, movies, shopping and quality time for family and friends.

Journalism is for the better part erratic and cruel. But when all goes well, it can also be euphoric, electrifying and elevating. It can strip a journalist of the ability to ever imagine life as anything else. For, the pen doesn’t just sit there. Life must happen on a journalist’s watch, for journalism to exist. No other profession has this defining requirement as its basis. So, even though a widely-read survey put a newspaper reporter’s job at the 200th spot in a list of 200 best and worst jobs of 2013, the world has to come to an end for reporters to cease to be.

If journalism is thus the most trusted form of mass communication known to man, cinema is perhaps the most loved. Together they must make for a crackling pair. No wonder then that Citizen Kane, the film widely regarded as the finest ever made, is on journalism.

My earliest memory of journalism and cinema is from when I was about four years old. I would sit on the floor, at my grandfather’s feet and pore over Deccan Chronicle, mesmerized by the headlines and pictures. The world moved each time my grandfather turned a page. When I learnt how to read, I began reading the newspaper with him. It was always the sports pages first, because he began with the front page. Deccan Chronicle was a low brow daily with a circulation you didn’t argue with. It would run movie advertisements over two or three full pages. If you wanted to go to the movies in film-crazy Hyderabad or Secunderabad, you would refer to the Chronicle for the cinema listings— Hindi, English and Telugu.

But it wasn’t until after I had become a reporter in New Delhi, that I saw my first journalism movie— New Delhi Times. It was a 1986 Hindi film with Shashi Kapoor in one of his more meaningful roles as Vikas Pande, a reporter who rises to the editor’s post, and finds the world vastly different. It was gripping because not many movies explored the interplay between politicians, businessmen and editors in an India still awed by Indira Gandhi. Almost everyone who worked in the media, and anyone who was a Hindi heartland politician, saw New Delhi Times.

Back in the 1980s, Indian journalism was still fairly convinced of its integrity. Newspapers were the principal form of mass communication and the corruption now associated with the media hadn’t seeped in. Yet, New Delhi Times showed Indian journalists in a not so flattering light. Key incidents in the movie were interpreted and re-interpreted over animated discussions. I don’t recall a major deconstruct of the movie in print, but there were parallels drawn to incidents and people that journalists knew in real life.

Some of what the movie showed was ironically mirrored in the life of its director, Ramesh Sharma. It was a fairly regular pattern in the 1980s. Businessmen with money liked to make movies— atleast partly for the love of glamour and power. Sharma seemed to have political ambitions too and began to get close to members of the Congress party.

He was often seen in the company of Uma Gajapathi Raju, the wife of rich and feudal Andhra Pradesh politician Pusapati Ananda Gajapathi Raju. Ananda was a Member of Parliament and Uma too was elected to the Lok Sabha in 1989 from Visakhapatnam in coastal Andhra Pradesh. Sharma’s friendship with Uma didn’t work for either because Congress circles in Delhi believed she had access to the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. It was, therefore, considered inappropriate for Sharma, a mere filmmaker, to be seen in public with Uma. It is hard to ascertain the truth of this story but it was deliciously full of intrigue and journalists lapped it up. (Reportedly Uma later divorced Ananda and married Sharma and they have made many public appearances together and have jointly run a production company as well as a non-profit organization.)

However, despite the critical success of New Delhi Times, few Hindi films have since explored the vast and rich material that the lives of journalists have to offer. There are several films that make a passing reference to the profession— Mohra (1994), with Raveena Tandon as a reporter for the newspaper Samadhan, C.I.D. (1956) with a plot that revolves around the murder of a newspaper editor, Mr. India (1987) where Sridevi is a crime reporter hunting for a scoop, for a daily aptly named ‘The Crimes of India‘, Nayak: The Real Hero (2001) with Anil Kapoor as a television journalist who becomes chief minister for a day, Bombay (1995) in which Arvind Swamy is a journalism student, Guru (2007) which features a character based on Ramnath Goenka, the founder of The Indian Express, played by Mithun Chakravorty, Wake Up Sid (2009) where Konkona Sen Sharma is a journalist with Mumbai Beat and most recently Satyagraha (2013), where Kareena Kapoor plays a TV journalist covering an agitation inspired by Anna Hazare’s real life hunger strike to enact the Lok Pal bill in 2011, to name a few. But there are barely any with journalism at their core. Other than New Delhi Times, the only ones I can think of are Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro (1983), Naya Sansar (1941), Page 3 (2005), Rann (2010), Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani (2000), and Peepli [Live] (2010).

Hollywood, which has over the years invested more in realistic cinema, has far more journalism movies. Some of these are simply marvelous and can tell you in close to 90 minutes what it’s all about.

It is a popular belief that journalists are at risk from the subjects they are reporting on. This belief is based on the understanding that a journalist is always reporting on facts others want to hide because of their unseemly and illegal nature. This assessment is simplistic and barely ever true— especially in the metros.

Threat to journalists mostly comes from within the newsrooms they populate. Deep insecurities and unresolved issues get full play as media employees target each other. Often, editors add to the toxic mix with opaque, murky and constant shifting of goalposts. In my career, no one has ever remotely threatened me because of what I wrote about them. All the battles I either won, lost, or walked off from emanated in the newsroom. The problem, as always, is with your own.

The other critical equation is the one between a source and a reporter. This is the most sacred of all journalism relationships and unless one of them, the reporter or the source, goes rogue, not a force on earth can pry them apart.

The Insider (1999), one of the finest journalism movies of all time, gets both themes right. The film is about Jeffrey Wigand, a top executive who is about to show up big American tobacco firms for promoting addiction to nicotine and lying about it. It’s also about Lowell Bergman, the CBS journalist who helps Wigand go public in one of the biggest public health stories in recent American journalism. Russell Crowe as Wigand and Al Pacino as Bergman are magnificent.

They meet on several occasions at odd times in sundry locations, mostly in cars. In lashing rain and thunder, the source and the reporter pry every bit of information out of each other as they strive for the most treasured of journalistic traits: credibility. Family deserts the whistleblower under the incredible strain of telling the truth. And, inevitably, the source and the journalist end up targeting the other under pressure.

“I’m just a commodity. I could be anything worth putting between commercials,” Crowe snaps at Pacino. “You’ve been telling yourself that something happens when you get information out of people. You’ve been telling yourself that to justify having a good job. Having status. Maybe for the audience it’s just voyeurism that won’t change a fucking thing.”

Later in the film, in a conversation with Mike Wallace, the host of the show 60 Minutes, Pacino gets back. “I never left a source hang out to dry, ever. Not until right fucking now. When I came on this job I came with my word intact. I’m gonna leave with my word intact. Fuck the rules of the game.” Mike and Lowell argue over how far they should go for a story and to protect a source. And on what should be the moment where one lets go of loyalty to a news organization that has built up a legacy. This is a key question in our profession.

At one point in my career I had a source go into rage and panic at the last minute. It was, coincidentally, a public health story as well and was ready to go to print as the cover story of a magazine I then worked with. The source, a top doctor in a big hospital, froze over some agreed upon bits of the story that I had sent to him for fact-check before it went to print. He was a man of medicine, used to writing papers for medical journals. I had written the report in a manner that would allow an average reader to understand. Claiming I had trivialized everything, he pulled out of the story. It took hours of mediation by a common friend and several heated debates for the source to calm down. When this happens, it’s like your entire life is at stake. It’s about your word, your reputation, your integrity. Months of talking to a source don’t mean a thing. Each time there’s a big story, a journalist has to start all over again. Director Michael Mann gets this perfectly in The Insider.

The film also has wonderful side play between the corporate and legal wings of the CBS on one side and the editorial on the other. Mann does some of the finest direction over the past 20 years in Hollywood. He gets his casting right, and manages to recreate lifelike newsroom atmosphere with its many conflicts. As much as a single film can, The Insider opens up the world of journalism for its audience.

If The Insider is a tale of corruption and courage that plays out as a riveting thriller, His Girl Friday (1940) is a super screwball look at everyday journalism. Unlike The Insider it is not about a game-changing big story, which happens only now and then. It is about the basic instincts of a reporter and an editor and how their interaction shapes a newspaper. Cary Grant is in terrific form as Walter Burns, the cynical editor of The Morning Post, but Rosalind Russell is even better as the editor’s ex-wife and star reporter Hildegard ‘Hildy’ Johnson.

It is impossible not to relish the dialogues and delivery, which was always Grant’s specialty. Russell matches Grant’s sharp-talking word for word and their jousts are remarkable. In one memorable scene after Grant is just done getting a shave in his cabin, Russell has dropped by to announce she is marrying again the next day. In pops the City Editor of the newspaper.

“What do you want?” snaps Grant, “I’m busy. I’m busy.”

“I thought you’d want to know the Governor didn’t sign the reprieve. Tomorrow morning, Earl Williams dies and makes a sucker out of us,” the City Editor says.

“Oh, oh.”

“Well, what have we gotta do?” asks the employee.

“Get the Governor on the phone.”

“I can’t.”

“Why not?”

”Can’t locate him. He’s out fishing.”

“How many places to fish are there?”

”Well, at least two. The Atlantic and the Pacific.”

”All right, that simplifies it, doesn’t it. Get him on the phone.”

”And tell him what?”

“Tell him if he reprieves Earl Williams, we’ll support him for Senator.”

“What?”

“Tell him The Morning Post will be behind him hook, line and sinker.”

“But you can’t do that.”

“Why not?”

“Because we’ve been a Democratic paper for over 20 years.”

“All right, if we get the reprieve, we’ll be Democratic again. Now get out and get going. The Morning Post expects every City Editor to do his duty.”

And we are not even four minutes into the movie yet.

The movie splendidly lays out the gossip and cynicism of journalists in a characteristic Press Club as Russell goes digging for the facts about Earl Williams, who is about to be condemned to death. Absolutely rollicking.

Citizen Kane (1941) and All The President’s Men (1976) are the big daddies of journalism movies. Citizen Kane is almost uniformly celebrated as the greatest movie ever made in English. Orson Welles put in such a towering performance as the lead actor and the director that he didn’t need to make another movie. Like Harper Lee, it would’ve been just fine if he had chosen never to work again. Welles, however, did make more movies, but never again with the grand sweep of Citizen Kane.

The story of a newspaper magnate, Kane, the film busts the myth of American capitalism with an exquisite human story and genius filmmaking. As Kane’s newspaper circulation and clout rises, the owner-editor’s life falls apart. The mysterious magnate dies a lonely death. The meaning of his last word—Rosebud—remains elusive until the end. The word in the context of the film recalls a purity and innocence that the journalists in the film fail to understand because they have distanced themselves from the essence of life. There is no better metaphor for the dwindling relevance of the media.

Citizen Kane also brings to life the power a political journalist can wield. Policy can be dictated by stories he does and wars can be started. And with this power often comes megalomania.The editor-publisher’s megalomania in the film has since been amply displayed in several newsrooms across India. Citizen Kane, thus, is still a template for journalism movies.

An editor-publisher I once worked with in New Delhi began with the exemplary purpose of launching a world-class magazine that would help Indians make the right decisions— because they would be better informed by the sharp and superior journalism of the magazine. He soon began to distrust journalists and surrounded himself with people who said and did things to please him. The magazine became a platform to either attack the editor-publisher’s foes or to fawn on people he wanted to be friends with. The publication has still not recovered from the damage thus done. It was pure Citizen Kane every day in the newsroom there.

Equally powerful is the movie on the Watergate Scandal, the biggest investigative story of all time. In All The President’s Men (1976), director Alan J Pakula’s narrative follows Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman), reporters of The Washington Post, as they crack open a bizarre attempt by President Richard Nixon’s men to spy on the Democrats by bugging the Democratic headquarters.

The most famous source in history, Deep Throat, played by Hal Holbrook, leads the reporters with his legendary advice ‘follow the money’. I’ve thought of this line several times in my career as a reporter and editor. I once gave a reporter a difficult assignment. His brief was to investigate a senior BJP politician on whom I knew there was a lot of dirt, but whose personal and professional life revealed nothing. The reporter began with enthusiasm but gave up too soon. I had told him to forget everything else and trail a dubious Rs 3 crore deal to get to this man. Had he done that he would not have lost the story. I have given this advice to a lot of reporters I have worked with since and it has almost always come in handy. The Watergate report remains the benchmark of great journalism. Even today, every reporter dreams of matching the reportage on the Watergate Scandal, or of getting a bigger story.

Ace in the Hole (1951), directed by Billy Wilder, is another superb journalism drama. Kirk Douglas lives the role of a reporter, Chuck Tatum, who tries to make an ambitious comeback. Sacked from his job in a big city for drinking, slander and womanizing, Douglas arrives in dead-end Albuquerque. He walks into the office of a local newspaper’s editor and makes a pitch for a job. His biggest weapon is that he can hold an audience spellbound and he charms the staff of the small town newspaper that is practically in coma.

One day, a worker is trapped in a nearby mine and Douglas senses his chance. He strings the worker along, delaying his rescue, to turn it into a human interest story that captivates all of America. The media circus that builds and the denouement have been redone many times since, in several languages, but this is where it was done first and best.

The story takes charge of the reporter as he goes from cunning to slimy. When it all unravels, the reporter is back where he began, bereft of his soul and desperate to understand why it happens with him over and over again. Ace in the Hole is a lacerating masterpiece.

I’ve seen Ace In The Hole happen to many journalists. You get so obsessed with a story that you manipulate it to suit your ends. Then, when you’re found out, you become the story yourself. There was a senior political journalist whom I had held in high esteem at the beginning of my career. Then, suddenly, it came to light that he was fabricating interviews with senior politicians. A Congress Chief Minister bumped into the journalist at a party and said: “I’m so glad to have finally met the person who interviewed me.” The journalist eventually quit the profession. He does what is described as ‘liaison work’ these days.

In the world of Indian journalism, Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani and Peepli [Live] are successors of Ace In The Hole. They are possibly the best Hindi film satires on the country’s media. Both are wonderfully crafted. Director Aziz Mirza and producer-actor Shah Rukh Khan were ahead of their times when they tore apart the mad TRP race among news channels with Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani. In a sharp moment in the film, sponsors line up for the execution of a prisoner that is to be broadcast live on television.

Unfortunately the film meanders into a number of futile sub-plots that trivialize the film’s message and dilute its central idea, but the movie manages to pack in a punch. Today, India is awash with news channels doing exactly what Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani predicted they would— in ways so extreme that were the movie to be released now it might seem tamer than reality.

Peepli [Live], directed by Anusha Rizvi and Mahmood Farooqui is a tighter and more nuanced depiction of media hypocrisy in India. The tale of a media circus around a farmer’s attempted suicide in many ways mirrors Ace In The Hole and to an extent this diminishes the movie. But its attention to detail and deep roots in our cultural contexts makes it the hardest look at modern Indian television media. The absolute lack of integrity and skill in newsrooms comes through sharply.

The tendency of following the leader and not doing one’s own homework hurts Indian journalism badly. A few months before Peepli [Live] was released, I was in Vidarbha to report on 10 suicides of farmers that had taken place in 48 hours. I traveled around the region extensively and managed to track down the homes and families of the farmers. The story that resulted from this was the first to say that the farmers were not killing themselves only because of bad crop. They were dying also because they had taken loans to meet the grandiose demands of the communities they lived in, especially for lavish marriages. The local journalists had never written about this because it would bring in social reasons into what was until then believed to be simply agricultural strife.

But when they learned that I had reported from all over Vidarbha for the story, they started to call me. They were content to merely reproduce quotes from me instead of getting to the roots of the story as only they could have. Peepli [Live] rests almost entirely on the mainstream media cannibalizing the work of an honest, unsung local reporter.

That then is the list of my top seven journalism movies— starting from The Insider. When I am down and wonder if it’s worth putting up with the provocation and humiliation that journalism brings, these are the movies I turn to. And they never fail to pick me up because they remind me about why I got into the profession in the first place. They humble me and leave me raring to go, one more time.

My memories of both journalism and movies begin at my grandfather’s feet. I learnt early enough that everything can be beautiful from the bottom of the world too. Journalism and movies, both work well when the instinct is sharp and the ego blunt.

Journalism 107

ArticleSeptember 2013

By Vijay Simha

By Vijay Simha

Vijay Simha is an independent journalist based out of New Delhi who is still trying to recollect the drunken conversation he had with a magnificently sober Sunil Dutt 20 years ago. He is now a sobriety campaigner and counsels alcoholics and addicts when he isn't writing. He has been Executive Editor at Tehelka magazine and worked for two decades alongside some of the most luminous names in Indian journalism at Patriot, The Pioneer, and The Indian Express. He has managed newsrooms and helped launch two magazines and a newspaper in English. He has reported and commented on Indian politics, issues of the day, and society in hundreds of articles over the years. In the social sphere, he has been Editor with Greenpeace and also worked with Gene Campaign.