-

Naaz Theatre | Purva Gadre for TBIP

Naaz Theatre | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

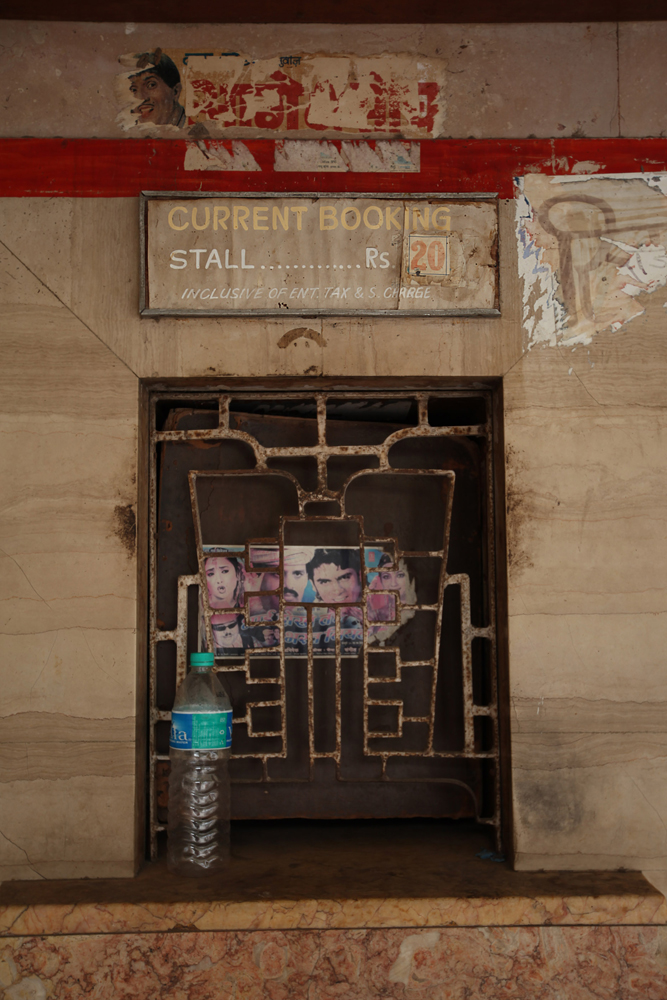

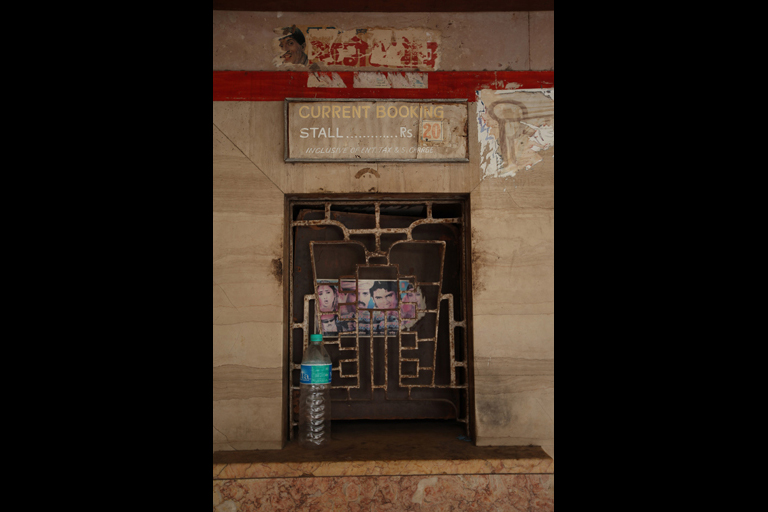

The Naaz booking counter that has now shut down | Purva Gadre for TBIP

The Naaz booking counter that has now shut down | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

The Naaz Theatre lobby with a statue from Gemini Studios | Purva Gadre for TBIP

The Naaz Theatre lobby with a statue from Gemini Studios | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

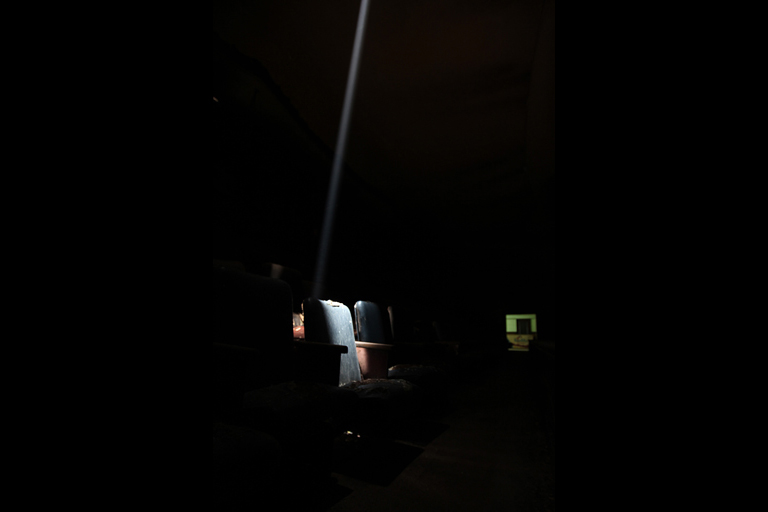

Ground floor seating at Naaz | Purva Gadre for TBIP

Ground floor seating at Naaz | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

A balcony view at Naaz | Purva Gadre for TBIP

A balcony view at Naaz | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

The once coveted Naaz Theatre seats | Purva Gadre for TBIP

The once coveted Naaz Theatre seats | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

The 'cry boxes' at Naaz Theatre | Purva Gadre for TBIP

The 'cry boxes' at Naaz Theatre | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

The Naaz balcony | Purva Gadre for TBIP

The Naaz balcony | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

The projector room at Naaz | Purva Gadre for TBIP

The projector room at Naaz | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

Old film cans next to an image of the goddess of wealth at the Naaz projector room | Purva Gadre for TBIP

Old film cans next to an image of the goddess of wealth at the Naaz projector room | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

A cracked mirror along a corridor at Naaz Theatre | Purva Gadre for TBIP

A cracked mirror along a corridor at Naaz Theatre | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

Popcorn machine at Naaz | Purva Gadre for TBIP

Popcorn machine at Naaz | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

An old chandelier grid and a defunct ice-cream box | Purva Gadre for TBIP

An old chandelier grid and a defunct ice-cream box | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

Jubilee trophies outside the office of Naaz owner R. P. Anand | Purva Gadre for TBIP

Jubilee trophies outside the office of Naaz owner R. P. Anand | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

Naaz Building | Purva Gadre for TBIP

Naaz Building | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

A man walks along a corridor with distributors' offices on either side | Purva Gadre for TBIP

A man walks along a corridor with distributors' offices on either side | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

Bhojpuri and B grade film posters outside the office of a film distributor at Naaz building | Purva Gadre for TBIP

Bhojpuri and B grade film posters outside the office of a film distributor at Naaz building | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

Devendra Shah, one of the older distributors at Naaz building | Purva Gadre for TBIP

Devendra Shah, one of the older distributors at Naaz building | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

Distributors at Naaz | Purva Gadre for TBIP

Distributors at Naaz | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

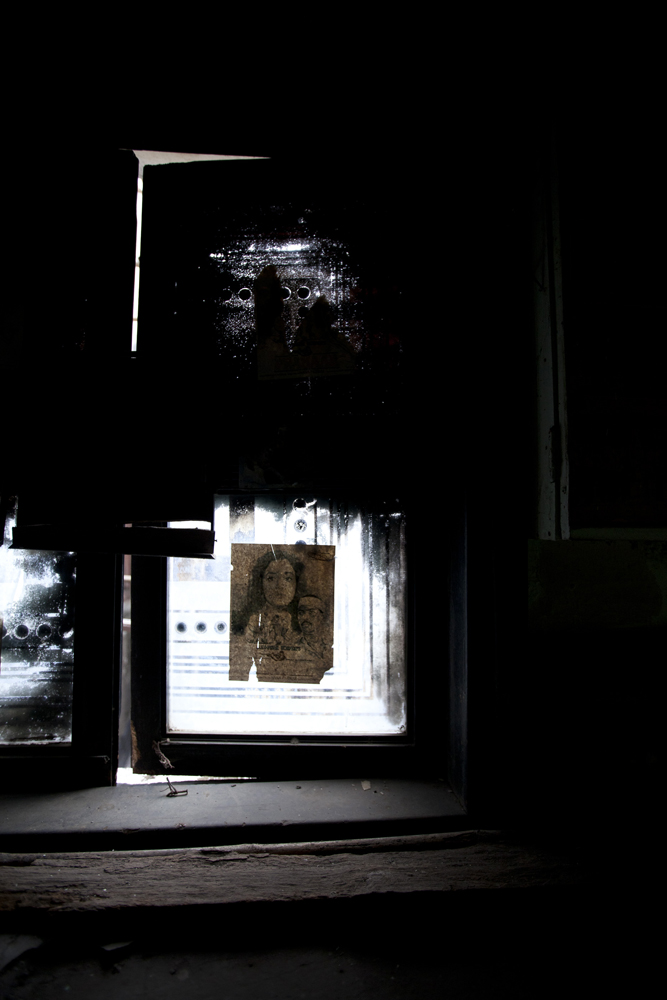

A window at Naaz with the newspaper cutting of an old black and white film advertisement stuck to the glass | Purva Gadre for TBIP

A window at Naaz with the newspaper cutting of an old black and white film advertisement stuck to the glass | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

A landing on the Naaz building staircase | Purva Gadre for TBIP

A landing on the Naaz building staircase | Purva Gadre for TBIP -

An empty tea cup on old film cans at Naaz building | Purva Gadre for TBIP

An empty tea cup on old film cans at Naaz building | Purva Gadre for TBIP

A story of one of Indian cinema’s most compelling institutions, that will soon be extinct

The man sitting in front of me was a producer, distributor, director and an actor. He didn’t look all of these things. In fact, he didn’t look any of them. Prakash Ahlawadi wore a faded grey shirt, a pair of brown trousers that seemed to be too short for him and a pair of sandals, one of which was torn. He was dark and had a mustache, and a face whose features you wouldn’t care to remember if you saw them on the road. Or in a film. He agreed to talk to me after I offered to treat him to tea. He is the only man I know who has spoken to me seriously about porn.

We were at a canteen, adjacent to an old movie theatre, with chipped, swinging saloon doors, more suited to a seedy bar from the sixties. So was this man. Around us were more, like him, dressed like him, who validated his claim of being a producer, distributor… whatever. They claimed to be so too. And joined us in speaking about porn. Then they spoke about the movie business and how the Hindi film had lost its family values and become a more individual affair over the years. The canteen had flimsy metal tables and old wooden chairs. It was a smallish, plain looking 10 by 12 feet space.

Outside, there were enormous film posters and hoardings. Hollywood blockbusters made to sound more garish than their creators would have ever intended them to, by dubbing and titling them in Hindi. Samundar Ke Lootere for Pirates Of The Carribean. Naga for Anaconda. And Husn. The last was the title of a “sexy film”. That’s what they called soft porn. It had just released and been washed out. “You have to know where to put a sexy film,” said Ahlawadi, with a grave face. “It won’t work everywhere”.

***

This was six years ago. Now the canteen, and the theatre, is shut. You have to stand back considerably to be able to see the mammoth structure in its entirety. In all its decrepitude. A vast art deco style theatre, built in 1952, it looks just about ready to collapse under the weight of history. Adjoining it is a building seven stories high, called a sky scraper in the era when it was made, a few years after the theatre. When Bombay didn’t have nearly as many tall buildings as it does now.

Both of these structures are shorn of paint, mostly, and they reveal, brazenly, the bare concrete that they are made of. Standing out on the edifice are four big bold letters that retain only a hint of the red they once were: N-A-A-Z. Meaning pride. Naaz Theatre. Naaz Building. Or just Naaz.

This immense whirlpool of decay, just off Mumbai’s Lamington Road, was once the epicentre of the Hindi film business. Its stock market. Every producer, distributor and exhibitor worth his salt would have an office in it. Mid-week the murmurs would start, the bargaining would begin, and by Friday films would be bought and sold. An Irani cafe nearby, now shut, would host a bunch of producers and distributors who had watched the trials of these films and who would talk about what would work and what wouldn’t. Which hero would be the next star. The next big director on the block. The money-spinners and the dabbas (literally meaning ‘boxes’— slang for flops in these parts). Among the people visiting this cafe would be giants like Producer-Distributor Gulshan Rai and Producer-Directors B. R. Chopra, Yash Chopra, G. P. Sippy, Nasir Hussain and Shakti Samanta. Legends like film stars Raj Kapoor and Dilip Kumar. And Amitabh Bachchan, when he wasn’t Amitabh Bachchan. When he was one of many actors who would visit the Irani cafe for a break. When the men at Naaz were still debating whether this tall fellow with a hoarse voice would last in the movies, and what on earth he was doing with that short actress Jaya Bhaduri at the premiere of Dev Anand’s Hare Rama Hare Krishna?

This was a time when the success of a Hindi film didn’t rely on a single week’s collection at urban multiplexes, but at least a few months’ draw at single screens throughout India— including small towns and villages. These proud men of Naaz were said to have a finger on their country’s pulse more than its politicians did.

One of the earliest trade reports also emerged from the Irani cafe close to Naaz. The latest gossip from its addas (a colloquial term for free-wheeling discussions) would be culled into cyclostyled sheets of paper called the K. T. (Knowledge Transfer) report. Then, one of the film producers who was a regular at the adda—B. K. Adarsh—began the country’s first trade magazine: Trade Guide. Its USP was a column called Naaz Samachar (Naaz News). Here are more recent snippets:

“NAAZ SAMACHAR

April 13, 1996

by K Z Fernandes

It seems to be a revival season for black and white movies. After the revival of Woh Kaun Thi? On 29th March at Maratha Mandir (mat.), as many as three films–DOSTI, PARASMANI and MADHUMATI–coincidentally, all jubilee hits in their first-run, were released at Minerva (mat.), Shalimar and Nandi, respectively last week. What’s more, another B/W fare, the Sohrab Modi-Dilip Kumar-Meena Kumari starter YAHUDI will be released in the near-future by none other than Shringar Films. To promote the film, Shringar Films have displayed an eye-catching hoarding in the vicinity of Naaz. The hoarding is beautifully painted and every passerby spares a few minutes to have a look at it, while some even murmur the famous lines from this film— ‘Yeh Mera Deewanapan Hai.’

“April 20

The management of Usha, Kolhapur has devised a unique scheme for audiences watching DILWALE DULHANIYA LE JAYENGE. The prizes distributed in the 6 p.m. show include audio cassettes of D.D.L.J. (for those in lower stalls), caps and T-shirts carrying the logo of the film (for viewers in Upper Stalls) and attractive wall-clocks (for the Balcony class). That’s a good scheme.

Publicist Mukesh G Vasani (of New Ravi Arts) has installed a lamination machine in his office at Jyoti Studio Compound, Kennedy Bridge, Mumbai.”

And that was news too. The installation of a lamination machine at a publicist’s office. Because the proud men of Naaz were an incestuous lot. And yet they were visionaries of sorts. The curve of Naaz’s trajectory of success rides on the great wave of India’s Golden Age of filmmaking (from the 1940s to the end of the 1960s)— and outlasts it until the end of the flashy eighties.

***

Now it’s over. I’m back at the Naaz Theatre after six years and I can see stray dogs wandering about its grand insides. At the lobby, in between two sofas, stands a pristine white statue of one of the Gemini twins (emblems of the erstwhile Gemini Studios— that used to make the biggest Tamil movies at one time) blowing his bugle to the sky. Flanking him are two cherubic figures, one holding a fox, the other a basket of fruits. “Wahaan hai, do shaitan (There they are, the two scoundrels)!” whispers R P Anand from behind me. R P Anand, the owner of Naaz, the last proud man standing, looks like he has walked out of a stylish postcard from the 1950s. His suit seems to be cut perfectly, but from a different era. His smart tie, sharp features, fair taut skin and slight rotundness make him look like a pinched, slimmer, Alfred Hitchcock. This gets accentuated when he tells you stories— he smiles, his eyes grow wide and shine, his eyebrows rise, he comes alive.

But, unlike Hitchcock, Anand was never tempted to make his own films. He states proudly that he has always been only an exhibitor, “not in the film business”. “Exhibitors were the most respected people in the city,” he says. Unlike film people, who were looked upon with a degree of scorn in the fifties and sixties because they worked with Jewish actresses and tawaifs, and whose business was so uncertain that a change in public appetite for a kind of movie could ruin them; the exhibitor, like an urban zamindar hosting nautch girl sessions, would merely be the man who presented the entertainment.

“VIPs would always approach me for prime seats to the movies,” Anand remembers. Ministers, policemen, income tax officials…

Anand was in his twenties when he was sent to look at this 900 seater theatre, then called West End, and the building adjoining it, and see whether they made for a good business deal for his family. They acquired both in 1963 from Keki Modi (brother of famous filmmaker Sohrab Modi). Before West End the spot had a different theatre that would show Marathi and silent films— which was demolished to build the new one that still stands. After the Anands bought it, after it became their Naaz, they showed only Hindi movies.

Devendra Shah, one of the older distributors at Naaz, is by everyone’s vote (including Anand’s) the best raconteur of its stories. The portly man is dressed in a shirt, trousers, and a pair of sports shoes when I meet him. “When I was twenty I would hang out with fifty year olds regularly,” says Shah. “I would love to listen to what they had to say, because history is history.” Shah explains the reason the Naaz building became such a hub was because: “The big studios in the fifties, like Jyoti, Rooptara and Ranjit, were located around it, so it made sense for everyone to set up office here to sell their movies.” The fifties saw many filmwallahs come into Mumbai from Pakistan after the Partition, he says, and the hub grew.

Anand’s family came from Pakistan too, from Punjab where they had swathes of land and extremely profitable businesses. “We had to leave everything behind,” he remembers bitterly. But they rebuilt themselves. They established themselves as contractors and financiers in Delhi, then ventured into other businesses. Anand moved to Bombay to develop the family’s interests here. Between three and five pm everyday, he still attends office at Naaz theatre.

Behind the statues in the lobby is a tall gold and silver glass panel that some say is from the sets of Mughal-e-Azam, one of India’s biggest period epics. Fancy iron grids, that once held chandeliers, remain fixed on the ceiling. Along the corridors of the theatre are round glass mirrors, mostly cracked, embellished on their fringes with stained glass work. Peer into one and, reflected in a cracked spider-web of history, you will see a vintage popcorn machine.

“I remember when the popcorn machine came in,” says Twinkle, Anand’s son who is thrice his size, chortling with glee. “People would just crowd around it to look, with their children, even those who couldn’t afford it would watch the corn go ‘pop’.” We’re in Shah’s cabin at his office on the first floor at Naaz. Behind him is a large image of the Hindu deity Mahalakshmi: the goddess of great wealth. Shah was talking about the days when Naaz represented great wealth to so many. Then Twinkle, who was passing by, decided to sit in on the conversation. Shortly, we were joined by the owner of another of the city’s stately old theatres called Capitol, located right outside Chhatrapati Shivaji Station. He didn’t want to be named in the article, but couldn’t resist being a part of the discussion. Then another distributor, who also wishes to stay unnamed, joined in. It’s been hours since we began speaking and this has become a Naaz adda without us knowing it. We’ve dissected the business, and moved on to general topics of interest: trends in Indian economics, politics and public psyche over the past four to five decades. It’s pretty surreal because Shah has a tea boy called Aatma Ram (aatma, in Hindi, means spirit or ghost) and every now and then in the middle of us chatting he screams: “Aatma Ram, chai lao (get the tea)!”

“Naaz, one of 16 theatres in Bombay, was considered lucky for producers to premiere their films in,” Shah tells me. Most films launched here would go on to run for a ‘silver jubilee’ (what men in the trade use to refer to a film running for 25 weeks). Some would make it to a golden jubilee (50 weeks). And some the diamond jubilee (60 weeks). Trophies for such jubilees would be given to the exhibitor and Anand’s office is so crowded with them you feel they’re closing in on you. Junglee, Waqt, Pakeezah, Teesri Manzil, Yaadon Ki Baraat… some of Hindi cinema’s most famous films have been premiered at Naaz. The trophies are everywhere— on shelves just outside the office, occupying more than half of Anand’s desk, on every available mantel or on a closet top. The accomplishments of half a century in Hindi cinema, measured not by how much a film collected but by how long it stayed.

“Not anymore,” says Twinkle. Films don’t stay this long anymore. They are shunted out.

“Now if a film finishes three days the exhibitors say to it: Dhut!” He barks at me, as if I were the unfortunate movie of today, being shooed away.

“Dhut!” Shah seconds him.

“Dhut.” repeats the unnamed owner of Capitol, a silent handsome old man with a gentle smile, quietly transforming this expression of put-down into a philosophical sigh.

“Godown mein jaao (Get into the godown)!!!” continues Twinkle, still talking to the make-believe film of today whose success is measured only by its box office collection. This is Twinkle’s crescendo, delivered like a sentence of banishment from an emperor in a period drama. He sweeps a large arm majestically, pointing to the door. Back in the days of the jubilees, when a film was let go of at a theatre, its reels would be stored in godowns. Today, with most theaters having gone digital, such film reels aren’t really used in the first place. But Twinkle, swept up in his act, has chosen to ignore this.

Shah says his tryst with the movies began with going to watch films like Dev Anand’s Munimji seven times. Twinkle remembers a man who watched Hum Kisise Kum Naheen 37 times (he had asked him curiously whether he was having trouble “getting the plot”). But their larger point is that a film was given time to pick up collections, time for word-of-mouth to spread. If it was good, it was given the honor of being re-watched. Shah remembers a black marketeer, with an office in the Bombay suburbs that had a Naaz signboard, who would hoard and sell tickets for Naaz shows at exorbitant prices. Sometimes, if a film didn’t work, it would be shot again and re-released (Jwalamukhi, starring Waheeda Rehman, was one such film).

Things changed with the corporates and the multiplexes coming in, in the noughties. With the Hindi film business being granted industry status by the government in 2000, loans could be secured for the movies from banks and finance companies. This brought in local companies like Shree Ashtavinayak Cine Vision Ltd. and Reliance Entertainment and multinationals like Disney and Viacom. To buy their way in, they offered far more than current rates to make a film, and production costs and star actor fees got hiked to more than thrice the amount suddenly.

Meanwhile the multiplex chains boomed, charging six times as much on tickets. The new producers could now make up more money on a week’s earning than they had earlier been able to make in months. There was consequentially a lot more money, and many more films. But the Naaz distributor lost his place of pride.

“There is no way we can afford to buy a film now,” says Shah. Shah, who began his career as a distributor by buying Jaya Bachchan’s (then Jaya Bhaduri) 1974 hit Kora Kagaz, took over this office from Standard TV, one of India’s first TV importers. Twinkle recalls that the first VCR to have been imported into India was bought by his brother. But these devices hardly made a dent on the pre-existing model of the film business. The multiplexes and the corporates did. Most distributors who ran their own enterprise from Naaz once now work for the corporates. “It’s the same thing in a way,” says Shah. “Because the corporates don’t really understand the business of film (where to sell, where to buy, how to break up the distribution of a film into territories). We do. It’s just that we don’t own the films we deal in now.” Instead, they’re “agents”. They earn commission or salaries for films they sell— unlike earlier where they would get all the profits on films they owned.

More significantly, they no longer control the fate of Hindi cinema. There was a time when Bollywood was them. Bollywood would come to them. The advances they paid a producer on a film would finance the movie. If it didn’t make money, the next film by the same producer would be pre-sold to the proud men of Naaz at a discount. Now they go to Bollywood. They barely control their own fates.

***

Save for some. Anil Thadani is one of the few independent distributors in the business who’s still making money. Big money. He bought the rights for Dirty Picture, last year’s Vidya Balan starring blockbuster. This year, he bought Agneepath, the wildly successful remake of a 1990 classic. Word around Naaz is that Thadani manages to buy these films because he collaborates with big producers like Karan Johar and Ritesh Sidhwani who’re willing to partner with him. They’re willing to partner, because he rarely goes wrong in his choice of movies to buy, or theatres to distribute them in.

Thadani meets me by the pool at the Otter’s Club, a posh member’s only club by the sea in the suburb of Bandra. He is slim, chiseled and sure of himself. He points out that the corporates coming in means more money for the industry, even if “distributors aren’t getting as much of a share in the pie as they used to.” He believes the corporates are here to stay. “You have to move with the times or you get left behind,” he believes. He’s planning on moving out of his fourth floor office at Naaz soon, to a more convenient location in Bandra. “Now with communications having gotten so much better, you don’t really have to have all the stakeholders in one place for the business to work,” he says.

***

The men who will stay back at Naaz are less comfortable with the pace at which India is changing. “Do we even have a government today?” asks Twinkle, his eyes ablaze at our Naaz adda in Shah’s office. “The corporates are a passing fad,” Shah argues. “There was a time, smugglers used to finance films— the underworld. They didn’t last. The corporates are like that. They will come and go.” But the corporates aren’t just Indian companies, I point out. They’re big multinationals. “Like China,” says the unnamed distributor, who was silent so far, bringing the discussion back to where it had started. We were talking about how Chinese goods are flooding the markets everywhere and the Indian government isn’t doing anything. That’s when Twinkle asked whether India even has a government today. “Jiski laathi hai na,” he says. “Usi ki government hai is desh main (the government in this country serves only those who wield power).”

A high-rise stands tall behind Naaz, many times its size, whose height can be estimated only if you crane your neck out of this building’s windows. Traffic noises from the main road creep into the sudden hush that has filled the room. “Today, to do anything,” says the quiet gentlemanly owner of Capitol. “You have to have your own private army.”

***

“If things turn back, I’ll make it even more beautiful than before.”

Anand stood in front of a cry box, six years ago, when he said this to me. The theatre was empty and still and dark, but I thought I could see his eyes well up. There was a lump in his throat as he spoke. Cry boxes were glass enclosed sound-proofed cubicles at the far end of the theatre’s ground floor, where families could watch films with bawling infants, without disturbing the other viewers. Families would come in hordes. Families of eight, or fifteen, or more. Joint families mostly. And not just for occasions like birthdays, festivals and weddings, as Twinkle says: “film watching was a family affair”. The first three weeks of a film would almost always be booked by families and the college going youngsters.

The latter would fashion their clothes after their favorite stars. “This trend was given a fillip when the colour movies came in,” says Shah. That’s when the distributors made the most money. It’s when their “Silver Jubilee Era” began. Shah remembers, particularly, Shammi Kapoor’s Junglee— one of the earlier colour hits. He and Twinkle and the unnamed Capitol owner and unnamed distributor recall how strictly stereotypes applied to each star. Shammi Kapoor, the rebel star. Dilip Kumar, the tragedy king. Dev Anand, the romantic hero. Rajesh Khanna, the new romantic hero. Rishi Kapoor, the lover boy.

Shah remembers buying Rishi Kapoor’s second film after his first—Bobby—completed its Silver Jubilee. Called Zehreela Insaan, it was the remake of a Kannada film Naagarahaavu, by the same director, that had Kapoor in the role of an angry protagonist, brimming over with angst— a 180 degree departure from the infatuated college kid in Bobby. “Naagarahavu had broken all box office records,” says Shah. “And Zehreela Insaan had excellent music by R D Burman (the famous O Hansini was one of its songs).” But the film didn’t work. The public refused to see Rishi Kapoor in this mould. He had to go back to playing lover boy in movies like Rafoo Chakkar and Laila Majnu to get the crowds back in.

Distributors would send their men to theatres to mingle with the audiences and determine whether a hero or heroine was working in his or her current avatar. Often the stars would try and observe the audiences, while remaining unseen themselves. “Manoj Kumar would be at Opera House, because that’s where his movies were run mostly,” says Shah. “Biswajit would slip into the cry box at Naaz.” Dev Anand would be at Naaz too.

The glass fronts of the cry boxes shattered long ago and were removed. In them lie chairs, tossed over one another. And cobwebs.

A story goes that Dev Anand had entered the cry box to watch his audience watch him in November 1976, when Jewel Thief was released. Here’s what I’ve pieced together from various accounts of what happened that day.

He was observing them closely to see where they cheered and whistled, and where they yawned. In the interval, he was preparing to leave when, suddenly, he heard an uproar. “A crowd has gathered because word has gotten around that Dev Anand is here,” he heard people say. This flummoxed him, for he had taken great care not to be seen when he entered. How did they find out? Or, more importantly, how would he leave without being mobbed?

The mystery revealed itself soon after. Outside Naaz stood Sev Anand—Dev Anand’s lookalike who had re-christened himself with a similar sounding name—leaning against a cigarette counter. He wore the same checkered golf cap and corduroy jacket Dev Anand had on as the Jewel Thief. He tilted his head to one side in the same manner, and spoke like Dev Anand, uttering five sentences in one breath, emphasizing the last, nodding for emphasis. The crowd cheered. Then, when they realized this wasn’t Dev Anand, they laughed and cheered again, not knowing that the real star was well within ear-shot. Ironically, in Jewel Thief, Dev Anand’s character had worn the same outfit to try and look like another character who was a mirror image of his. And here he was, trapped in a glass box, waiting for the Sev Anand show to end.

Naaz is full of such stories and such images. The building seems to have sunk into the ground somewhat, and when you walk along its corridors you notice that the levels on each floor slope slightly into one another, lending it an Escheresque feel. Yet for all the surrealism you know “things will not turn back”.

Bombay, now Mumbai, the linear city, doesn’t always allow for a U-turn. Amitabh Bachchan made a U-turn. Dev Anand couldn’t. The most durable leading man in Hindi film history delivered 84 hits in a career spanning 115 films. But his last 10 films, released over the last two decades, were critical and commercial failures. One of these, incidentally, was Return of Jewel Thief. His last film, released in 2011, was Chargesheet. It stars an 88 year old Dev Anand, in the bright scarves and suede waist coats of his youth, next to debutant actress Devshi Khanduri, who plays a wannabe siren, with a Gibson guitar she pretends to strum, and an irrepressible desire to writhe. But for its star cast—which also includes veteran actor Naseeruddin Shah and another, younger, yesteryear star Jackie Shroff—it has all the makings of a ghastly B movie. A few months after it was released Dev Anand passed away on the 3rd of December at London’s Washington Mayfair Hotel.

Sev Anand, who came to Mumbai from a village in UP, tried at first to sell himself to producers at Naaz as a cheaper Dev Anand. They refused. He did, however, bag a tiny role in a lesser known film called Akalmand where he played I S Johar, wearing a Dev Anand mask, during a jewelry heist. Then he invested all he had into a film called Taqdeer Ki Baazi (a take on Dev Anand’s Baazi), which, appropriately, translates into ‘gamble of fate’. He enlisted the services of an actress he named Kalpana Karnik (Dev Anand’s wife was Kalpana Kartik) and a music director called S. D. Surman (inspired from the legendary S. D. Burman). After ten reels he had to shelve the film. Funds had dried up. Shah, who had once gifted Sev Anand a Jewel Thief cap, says Dev Anand “paid for his upkeep” after this. Then, in 2005, a newspaper report said Sev Anand had committed suicide. Perhaps because he was no longer needed. Dev Anand had taken to parodying himself.

Just like that, proud men go. R. P. Anand and Twinkle are planning on selling Naaz so that the land can be used to build a modern mall and banquet centre. “Please don’t ask that this be declared a heritage property,” Anand tells me. “I wouldn’t want that.”

And perhaps he is right in this. For Naaz—the pride of Hindi cinema’s glory years—to be refurbished into some sort of half-hearted tribute to itself wouldn’t do it justice at all.

Sun lo magar ye kisise naa kehnaa (Listen, but don’t say this to anyone)

Tinke ka leke sahaara na behana (Don’t grasp at straws)

Bin mausam malhaar na gaana (Don’t sing the Raag Malhar, when it isn’t the season for it)

Aadhi raat ko mat chillana (Don’t scream in the middle of the night)

These are the lyrics of an old Raj Kapoor song from Shree 420. The film wasn’t released at Naaz, but it may have been bought and sold here. The words hold. Naaz is mean’t to go. As its proud men were. Like Gemini Studios, in Madras—which was razed to the ground to make place for a five star hotel called The Park—with bits and pieces of it, like the statue at Naaz, scattered around the country.

Because that is the way of legends. To live on in other things long after they are dead. To keep coming back as unlikely fragments of the past. “Ab to sirf film ka tukda khareed saktay hain (Now all we can buy is a fragment of a film),” says a man who was once a distributor at Naaz, about how he can’t possibly afford to pay for the rights of a film for an entire territory anymore. He is telling me why he shut shop. He is one of many who did not go to work for the corporates. For pride can be broken, sure. Never bent.

Proud Men

ArticleOctober 2012

By Rishi Majumder

By Rishi Majumder

Rishi Majumder is Senior Editor at The Big Indian Picture