-

LP cover, Ab Dilli Door Nahin

LP cover, Ab Dilli Door Nahin -

LP cover, Tere Ghar Ke Samne

LP cover, Tere Ghar Ke Samne -

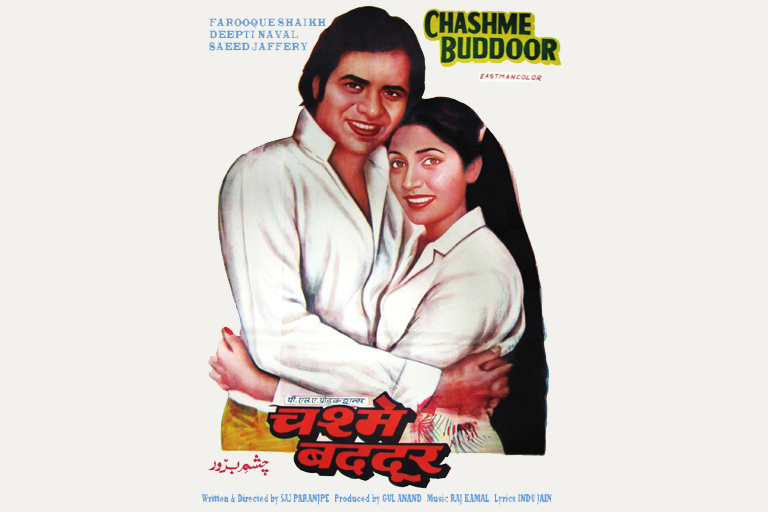

Theatrical Release Poster, Chashme Buddoor | Courtesy S.M.M. Ausaja, Collector and Film Historian

Theatrical Release Poster, Chashme Buddoor | Courtesy S.M.M. Ausaja, Collector and Film Historian -

The New Delhi Times masthead and front page being typeset (Still from New Delhi Times)

The New Delhi Times masthead and front page being typeset (Still from New Delhi Times) -

Theatrical Release Poster, Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye!

Theatrical Release Poster, Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye!

Mihir Pandya tells you about 5 Delhi films that you must watch, and why

The Plea: Ab Dilli Door Nahin, 1957

Many regard 1957 as a watershed year in Hindi cinema. One of the films released that year, along with Naya Daur, Pyaasa, Do Ankhen Barah Haath and Mother India was Ab Dilli Door Nahin.

Produced by Raj Kapoor and directed by Amar Kumar, Ab Dilli Door Nahin is a perfect example of a film made and set in a young nation-state. It is the 10th year of Indian independence. The state is slowly beginning to establish its authority over a new citizenry. And for that the state’s justice system becomes its primary tool. You can read other famous Raj Kapoor films like Awara, Shree 420 and Jis Desh Mein Ganga Bahti Hai along similar lines as Ab Dilli Door Nahin.

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru has become the symbol of hope for an entire nation. His elusive promise of Justice For All becomes a personal ray of hope for Ratan, a small boy living in a village. He begins to believe Nehru’s promise is his only chance to save his father Hariram’s life, who has been falsely implicated in a murder case. Holding on to his faith, Ratan (played by Master Romi) embarks on a long journey to Delhi, the capital of the promised nation, with a plea for his father’s innocence.

Here’s a conversation that establishes the enormous significance of Delhi, and Nehru, in those days. In the scene Ghasita (Yaqub), a kind-hearted pick-pocket who accompanies Ratan to Delhi, is talking to Mukunda (Anwar Hussain), the real culprit of the murder, and Ratan. Ghasita is witness to the fact that Ratan’s father was not at the scene of the crime at the time of the killing, but the local police refuse to take his word for this because of his own dubious criminal record.

Ghasita: Come on, we’ll go to Delhi.

Mukunda: Delhi? Do you even know anyone there?

Ghasita: Yes, our Masita (another character) lives there.

Mukunda: The way you’re saying it, one would think you knew Pandit Nehru.

Ghasita: Who doesn’t know Pandit Nehru? He’s like a father to all of us. If he doesn’t listen to us, then who will he listen to? I’ll fall at his feet first, then beg for justice. I’ll tell him how, with an emperor of justice like him around, a child is being treated so unfairly. (To Ratan) Come on, we’ll free your father and send the real murderer to the gallows.

Ghasita goes on to say: What’s Delhi? I’ll go all the way to God if I have to.

The film also has memorable music by Dattaram with lyrics penned by Shailendra and Hasrat Jaipuri. Songs like Chun Chun Karti Aayi Chidiya (that used animation way ahead of its times), Ye Chaman Hamara Apna Hai and Lo Har Cheez Le Lo Zamaane Ke Logon are all markers of their times.

The Delhi that Ratan finally reaches has trees lining the India Gate and a visibly clean Yamuna coursing its veins. Here he meets Nehru finally, presents Ghasita as a witness, and secures a pardon for his father.

Raj Kapoor had initially persuaded Nehru to appear in this last scene of the film, where the child met him. His son Rishi Kapoor recalled in an interview that his father had said to Nehru that this would put his new government “on a high pedestal, and bring the desired credibility”. However, when it came to shooting the scene Nehru backed out for “reasons”, according to Rishi, that were “best known to him”. Instead, stock shots of Nehru were used for the film. Rishi Kapoor believes this took away considerably from the film. “As the whole film was based on the child’s meeting with the PM which didn’t happen, the film fell flat. Obviously no one could empathise with it”, he said.

The Capital Is For The Young: Tere Ghar Ke Samne, 1963

Vijay Anand’s 1963 classic Tere Ghar Ke Samne is one of the best urban-youth love stories to have emerged out of Hindi cinema. Like a lot of other films produced by Vijay Anand’s production house, Navketan, in its early years, this film had a distinct modern sensibility that set it apart from other great production houses of the era. The Delhi of Tere Ghar Ke Samne is a new metropolis that provides the protagonists Rakesh (Dev Anand) and Sulekha (Nutan) with the possibility of overcoming familial pressures and societal barriers.

Rakesh is an architect who is contracted to build houses, located one in front of the other, for two warring businessmen. Neither of these businessmen know that he has been contracted to build the other’s house as well and each demands that his house be better than his rival’s. Rakesh is also the son of one of these businessmen, whereas Sulekha, whom he is in love with, is the daughter of the other. When the houses are finally unveiled, they are absolutely identical. Rakesh uses the replication of architectural design as the ultimate ‘solution’ to end the one-upmanship between two families. Reflected in his tongue-in-cheek ingenuity is Nehru’s socialist ideals and his idea of his dream-project Chandigarh— a meticulously planned city with similar looking blocks of houses.

Tere Ghar Ke Saamne references Nehruvian ideology at other times as well. In one scene where Rakesh and Sulekha discuss how they can get married, when their fathers are at war, he says: “Cheeni tareeqa yeh hai ki main bandook le kar tumhare ghar mein aa jaun aur thaa thaa zabardasti tumhe tumhare maa baap se cheen loon. Hindustani tareeqa hai Panchsheel ka tareeqa… pyaar ka tareeqa (The Chinese way would be me reaching your house with a gun and snatching you away from your father. The Indian way is the way of the Panchsheel… the way of love).”

It is worth mentioning that when the film was in the making our capital’s first post-independence master plan was taking shape. This was the plan according to which Delhi’s development was carried out in the 1960s and 1970s. This plan elaborated the role of the Delhi Development Authority and laid clear provisions for the formation of independent colonies that would have their own markets and schools. You see the imprint of that powerful document in this romantic drama which begins with two businessmen bidding for residential land in a new Delhi colony at a government auction.

One of the lasting images from the film is that of the protagonist Rakesh, seated on a chair, while Sulekha’s house is being constructed in the background, reading a love letter written to him by Sulekha. She writes to him from Shimla describing how she wants him to build her room and how it has to be ‘open’ from all sides. He is reading the love letter and remembering his lady love, and all this while the construction work continues behind him.

“Maahaul achcha hai”: Chashme Buddoor, 1981

Sai Paranjpye’s Chashme Buddoor is about the space- physical and mental, that Delhi once provided to a generation that was in college in the late 1970s and early 1980s. A space for friendship, love and other delightful reveries. The capital wasn’t as densely populated then as it is now, and there were many public places like parks, or spaces on Delhi’s North Campus, where couples could find spells of privacy. This is in stark contrast with the city as it is today. Sometime in the early nineties the Delhi Police began to routinely raid such public spaces and oust young couples who had come to spend time there. This ridiculous practice, that continues to this day, has been dubbed ‘Operation Majnu’ by some TV channels.

Chashme Buddoor’s Delhi, a pre-‘Operation Majnu’ Delhi, is also bereft of the crazy urban development that the city has seen in the last 20 years. But it is not the ancient city of dilapidated monuments either. It is the long lost 1980s campus city rarely documented in cinema (the only other film that talks about this Delhi is a lesser known indie film directed by Pradeep Kishen: In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones). At the heart of the film are the vast and deserted New Delhi roads, laced by lush greens.

This is the Delhi inhabited by its three protagonists – Siddharth Parashar (Farooq Shaikh), Omi (Rakesh Bedi) and Jomo (Ravi Baswani), students sharing a flat and living outside of the familial structure (the only reason we know they even have families is because they keep receiving money orders from back home). It is also home to a paan and cigarette shop owner called Lallan miyan (Saeed Jaffrey), a character replete with old world charm and painstaking diction— who still uses archaic Urdu words like andagafheel (to vanish).

An enduring scene from the film is one where one of the protagonists, Siddharth, is out on a date at an open air restaurant, that used to be at the Talkatora Gardens. “Yahaan achcha kya hai (What’s good here)?” he asks the waiter, who replies: “Maahaul achcha Hai (The ambience is good)”. I went to the spot where the restaurant used to be, after re-visiting the film in 2010. A guard at the Gardens told me it had been shut down a couple of years ago. The Talkatora Gardens themselves seem to have faded from the city’s public memory despite being located in Central Delhi. The guard said not as many people came there anymore. I looked around and found a few couples sneaking intimate moments. The guard was disapproving of this. “This isn’t a family place any more,” he said.

In Dark Times: New Delhi Times, 1986

Directed by Romesh Sharma, New Delhi Times is one of Gulzar’s best screenplays. Like Ab Dilli Door Nahin, this film represents Delhi as India’s mighty capital, except three decades later it appears to have entrenched itself as the seat of corruption, concerned with little except power and money. Ab Dilli Door Nahin‘s naive dream of the capital as a temple of justice and progressive thinking is obliterated by the gritty portrait of Delhi as a cold and cruel metropolis, up for grabs by those who are determined to ascend the slippery slope of social hierarchy in any which way.

Two tracks play out parallel to one another in the film: one in Delhi, the other in the small town of Ghazipur (a district in Eastern UP). As Journalist Vikas Pande (Shashi Kapoor) traces the murder of an MLA in Ghazipur, and subsequent riots that break out in the district, all the way to a burgeoning politician-industrialist-

Most of the horrific events in New Delhi Times play out at night, which was possibly intended by Sharma and Gulzar as a suitable way of bringing out the city’s dark side. It is at night that a reporter who works for Pande is run over by a truck on a Delhi highway before he can tell him what he has found. It is also night when Pande and his wife Nisha (Sharmila Tagore) return home to find their beloved pet cat killed by way of a deadly warning. But Pande labors on through the dark believing he will be able to pin down an evil parliamentarian (Om Puri) who he believes is responsible for all this. Then he discovers that another political group in the city, as deadly the one he seeks to prosecute, has been using his zeal for this story to its own end. The last scene of the film has Pande writing an editorial which denounces both of these groups, resigned to the nightmare India’s first city has become.

On The Fringes: Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye!, 2008

Finally, a film that takes us into the back alleys of the formidable capital celebrated and lamented by the films listed above. In Dibakar Banerjee’s Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! Delhi isn’t the oppressive power-centre of New Delhi Times or the idyllic campus-city of Chashme Buddoor. And it definitely hasn’t turned out to be the well planned city Tere Ghar Ke Samne willed it to be or the citadel of justice Ab Dilli Door Nahin saw it as. Oye Lucky… is Banerjee’s uncovering of a city within Delhi, just below the class divide. The rambling mess of post-partition colonies aspiring to push into the cool colonnades of middle-class life in South and Central Delhi; setting itself apart and yet trying to elbow its way into the parade of the posh; endearing itself with its distinctly delicious dialect in one minute and letting its hypocrisies swell like the open gutter in the next.

Banerjee brings this part of the city alive by looking beyond the historicity that overwhelms the capital, relegating it to a campy tourist photo of an adolescent Lucky (the titular role, played by Manjot Singh and Abhay Deol) with his closest friend, shot to make it seem like they’re touching the top of the Qutub Minar.

Lucky grows up in a lower-middle class Sikh family living in a peripheral West Delhi colony. This has narrow filthy streets, electrical wires that hang loose from lamp posts, red chillies being dried in courtyards and old-style UHF antennae on the rooftops. Here is the Delhi of real-life-master-thief Devinder Singh, alias Bunty, whose life Oye Lucky… has been inspired by; the megapolis of a melee of North Indian migrants whose characteristic Jat twang transforms ‘Rajouri Gardens’ into ‘Raj-au-ri’.

An older Lucky thieves his way through his youth in search of a place where he can belong. When his father, who beats him up and neglects him, refuses to lend him his scooter he steals a motorcycle from a garage. He takes a girl out on it to “New Amar”, a seedy West Delhi restaurant that he can ill-afford. Later, he joins a gang to rob houses, then goes solo because he is betrayed by his partners-in-crime. He steals, among other things, a Mercedes, a TV, a laptop, greeting cards, a teddy bear, a photo frame and a pomeranian. He tries to buy his way into respectability by owning a Delhi restaurant, but is cheated again. As Lucky finally gets caught he is discussing a romantic but futile getaway with his girlfriend, across balconies in a West Delhi colony, even as his loot is being seized. These moments are all he can steal to keep.

Mihir Pandya is author of the book Shahar Aur Cinema: Via Dilli

Delhi 5

ArticleNovember 2012

By Mihir Pandya

By Mihir Pandya

Mihir Pandya is the author of the Hindi non-fiction book Shahar Aur Cinema - Via Dilli on Delhi in the movies. He is a research fellow at the University of Delhi, working on the subject of the contemporary city in popular Indian cinema for his doctorate. He has written for Nav Bharat Times, Tehelka magazine (Hindi), Kathadesh, Pratilipi, Jansatta, Vaak, Medianagar and Bahuvachan among other publications. He is sub-editor at the Hindi journal Banaas, and part of the editorial team at Chakmak, a children's magazine. He believes Deewaar is a bigger classic than Sholay.