-

Poster of Awtar Kaul's 27 Down, winner of National Award for Best Film and Best Photography

Poster of Awtar Kaul's 27 Down, winner of National Award for Best Film and Best Photography -

M.K. Raina and Rakhee in a Bombay local train in 27 Down

M.K. Raina and Rakhee in a Bombay local train in 27 Down -

A shot of what was then the Victoria Terminus (VT) Station, in the 1970s, from 27 Down

A shot of what was then the Victoria Terminus (VT) Station, in the 1970s, from 27 Down -

Another shot of VT Station from the film

Another shot of VT Station from the film -

Rakhee and Raina at Nariman Point. The film was shot with close lensing of the characters and handheld shots resulting in an immediate intimacy

Rakhee and Raina at Nariman Point. The film was shot with close lensing of the characters and handheld shots resulting in an immediate intimacy -

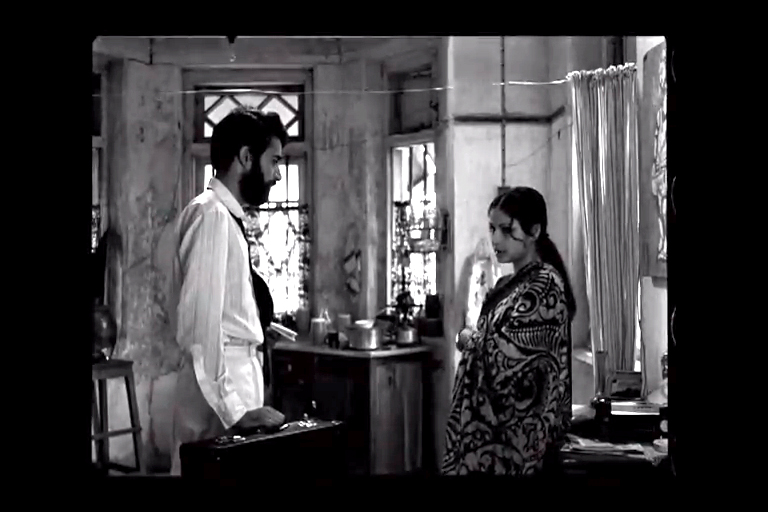

Raina and Rakhee in a still from 27 Down

Raina and Rakhee in a still from 27 Down -

Raina and Rakhee in 27 Down

Raina and Rakhee in 27 Down

Jai Arjun Singh on Awtar Kaul, 1973 and a cinematic what-if

A favourite parlour game for the nerdish movie buff is the contemplation of great cinematic years. Internationally, obvious frontrunners include 1939—when a breathtaking number of high-quality films competed for hall space before the disruptive theatre of WWII took over—and 1959-60, when at least half a dozen countries seemed to have New Waves in progress and such varied directors as Jean-Luc Godard, Kon Ichikawa, Otto Preminger and Georges Franju did magnificent work. But looking at Hindi cinema through the lens of hindsight, it seems to me that something special was in the air in 1973.

This is not necessarily to say that numerous masterpieces were unveiled in those 12 months— it’s more that one feels things were on the brink; that new routes and possibilities were opening up, and much might have happened differently but for a single coin-flip. Amitabh Bachchan’s career-altering role in Zanjeer—a part he got after bigger stars backed out—birthed the defining screen personality of the decade to come. Raj Kapoor’s Bobby, the year’s biggest hit, created a fresh idiom for rebellious young love. The writers Salim-Javed, having created the angry young man Vijay, were just wrapping up a Western-inspired script about an armless thakur hiring two mercenaries to rid his village of a dacoit. Meanwhile, beyond the mainstream, the so-called Indian New Wave was in its ascendency: M S Sathyu made the elegiac Garam Hava and Shyam Benegal directed his first feature Ankur. And for a sense of what lay ahead, consider the stream of youngsters who entered the Film and Television Institute of India that year: Naseeruddin Shah, Saeed Mirza, Renu Saluja, Kundan Shah, Om Puri and Vinod Chopra among them.

One of the less-known gems of 1973 is a film titled 27 Down, produced by the Film Finance Corporation (later NFDC) and directed by Awtar Krishna Kaul. I confess shame-facedly to knowing almost nothing about it until a few weeks ago, except for the fact that Kaul had died in a drowning accident shortly after the film was completed. (It was his first and last feature.) But watching it on a restored DVD print by NFDC recently, I was certainly very intrigued.

“Phir koi pull hai kya? Shaayad pull hee hai.” (“Has another bridge come? Seems like it.”) The first words we hear in 27 Down are the subconscious musings of someone who knows trains and train journeys only too well, and who feels like he has spent his life crossing bridges without getting anywhere. Sanjay (M K Raina), the son of a railway employee, has to forgo his art studies when his father insists he return to the family profession. In one vividly shot and edited early sequence, we hear the father’s voice dispensing platitudes (“Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise”) while the son does things in contravention of this paternal advice— eating the “unhealthy” bhel-puri he has been cautioned about, walking about the streets of Bombay late at night. It’s as if these small, inconsequential acts of defiance are a part-compensation for the bigger battles he knows he is destined to lose. Now a conductor himself, he lives—literally and figuratively—on the tracks, and measures his life in train sounds and distances. His relationship with a young woman named Shalini (Raakhee, already a mainstream star but well-cast here) is also affected by the demands of conformity.

In the language of facile categories, this is an art film— a subdued, slow-paced work about a non-heroic life. Sanjay inhabits a very different universe from that of the other hopefuls, dreamers or malcontents of 1973: the two-fisted cop of Zanjeer, the teenage lovebirds quelling the odds in Bobby, the brothers reunited in a nightclub through the power of song in Yaadon Ki Baaraat. (In one scene in 27 Down, “Chura Liya Hai Tumne” can be heard playing on a radio, leading one to speculate that Sanjay might—in one of those bursts of filial rebellion—go to see a late-night show of Yaadon Ki Baarat.) There is no triumphal narrative in Kaul’s film, not even a hint of it; the dominant image is that of Sanjay feebly saying “Par, Anna… ” (“But, Anna… ”) as his father casually tells him what his future holds.

But if this is a movie about a man with no future (made, as it sadly turned out, by a man with no future), it certainly shows an understanding of the possibilities available to coming generations of movie-makers. It has a kinetic visual sense, for one thing: jump cuts are effectively used to mark the passage of time (while also ironically commenting on the stasis in Sanjay’s life); freeze-frames, abrupt zoom-ins and zoom-outs suggest the blurring of real life with desires or unreliable memories. There is an element of fabulism in a scene where Sanjay, watching Shalini’s silhouette as she changes behind a curtain, is reminded of the Aphrodite statue that fascinated him as a child. And for all the soberness of the content, there is a sense of playfulness too, as in the early scene where children play in train formation and a song goes “Chuk chuk chuk karti gaadi”.

At the same time, themes are sometimes spelt out in the style of a chamber drama; a couple of the conversations play like deliberately theatrical monologues rather than naturalistic talk. This directness and purity of form reminded me very much of the work of the great directors Carl Dreyer and Robert Bresson, which is not to say that 27 Down reaches the heights of the best films made by those men— it has a fragility that you’d expect from someone making his first feature, and there are a few awkward touches: such as the underlining of an emotional moment with a jarring music score. But there is much promise here, as well as signs of a versatile sensibility.

And so, to another of those parlour games: the ‘What If’. If Kaul had lived, what might his subsequent work have looked like?

In a way it’s silly to make such speculations based on a single movie. But on the limited evidence we have, I think Kaul might have found a goodly middle ground between the “arty” and the “commercial” film. (Incidentally, the only other movie credit he has on IMDB is as assistant on Merchant-Ivory’s Bombay Talkie, which was a meta-commentary on commercial movie-making.) He would also quite likely have brought a new dimension of interiority to 1970s and 80s cinema— with films centred on the human face, where we are encouraged to look at a person not because he is doing something interesting but because he is interesting.

27 Down explores a character’s inner life to a degree rare in Hindi cinema (even non-mainstream cinema). This isn’t just done through voice-over—that would be lazy filmmaking—it is achieved through an artful bringing together of elements: cinematography and shot juxtaposition, performance, the use of background sound (when Sanjay reflects on his unusual childhood, we hear an infant crying somewhere in the compartment he is in). A year later, something comparable was achieved in Basu Chatterjee’s Rajnigandha, about the inner turmoil of a woman caught between the idealistic memory of a past love and the apparent monotony of a present one. But among major filmmakers of the decade that followed, I can’t think of anyone who did this with regularity.

Then there is the fact that 27 Down is shot (beautifully) in black and white— not a commonly used medium in Hindi films of the time, or since. The decision may have been dictated by resource constraints, but I prefer to think it was deliberate: Kaul and his cinematographer Apurba Kishore Bir make the most of the form, composing stunning location shots of Varanasi and Bombay, of juddering trains and busy train stations in the gloaming— places that are simultaneously filled with crowds and suggestive of deep loneliness. Perhaps, given some artistic freedom, he would have shown some of his contemporaries how resonant black-and-white can be?

To speculate further: given Kaul’s apparent willingness to work with mainstream performers, I could even imagine him doing something really interesting with Bachchan somewhere down the road. This is not as improbable as it sounds: the Zanjeer legacy makes it easy to forget that in 1973 AB also did fine work in such low-key films such as Saudagar, which might have taken his career in a very different direction— and that he continued doing commercially unpromising films like Alaap and Manzil after becoming a superstar. Imagine one of his better roles—say, the guilt-wracked ship’s captain in Kaala Patthar, punishing himself for a moment of cowardice—shaped and performed without the over-expository trappings of commercial cinema: done with discerning silences and close-ups and fragmented interior dialogue rather than with fiery dialoguebaazi. (And in black and white! Bachchan in a good role in a really well-photographed B&W film is one of our great missing cinematic treasures.) I think both the actor and the director might have been up to the task.

Quite possibly, none of this would have come to pass— there have been enough cases of directors who faded away after their first films. But watch 27 Down and you’ll probably agree that Kaul was among Hindi cinema’s most promising unrealised talents. The only film he made was about a frustrated, circumscribed life, but in the best of all alternate universes he might have found a way to lay new tracks to the places where he really wanted to go.

Off the beaten track

ArticleDecember 2012

By Jai Arjun Singh

By Jai Arjun Singh

Jai Arjun Singh is a freelance writer and journalist. He has authored a book about the 1983 film Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro and edited an anthology of film writing, The Popcorn Essayists: What Movies do to Writers. His blog Jabberwock (http://jaiarjun.blogspot.com) is a storehouse of his writings about literature and cinema, and also contains stray thoughts on tennis, parents-in-law, evil water tanks and other subjects. Jai loves the movies. He is Psycho obsessive and has mulled the possibility of having his mother preserved. Even though he pretends to be a purist he has occasionally, much to his shame, watched hard-to-access films on YouTube.