-

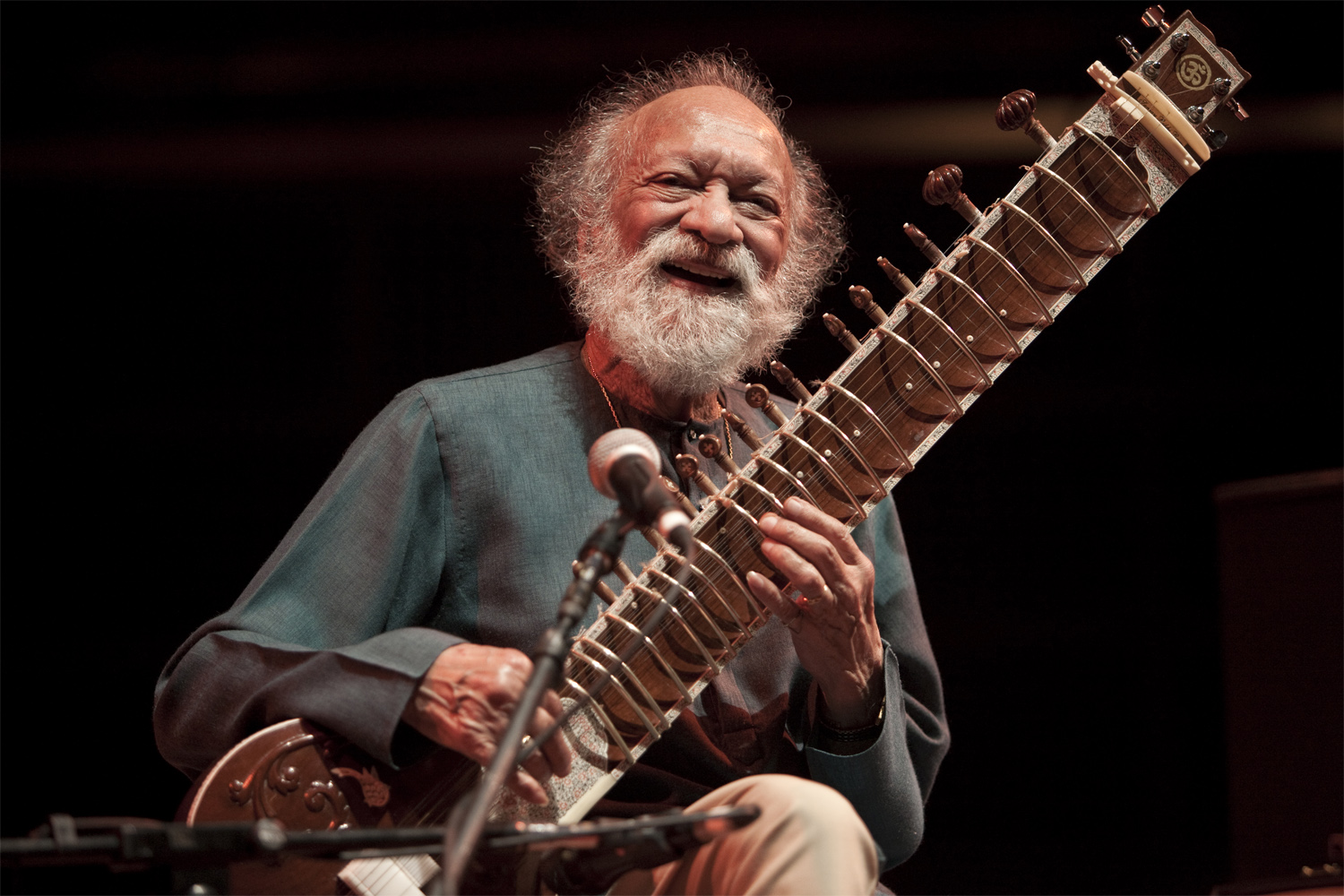

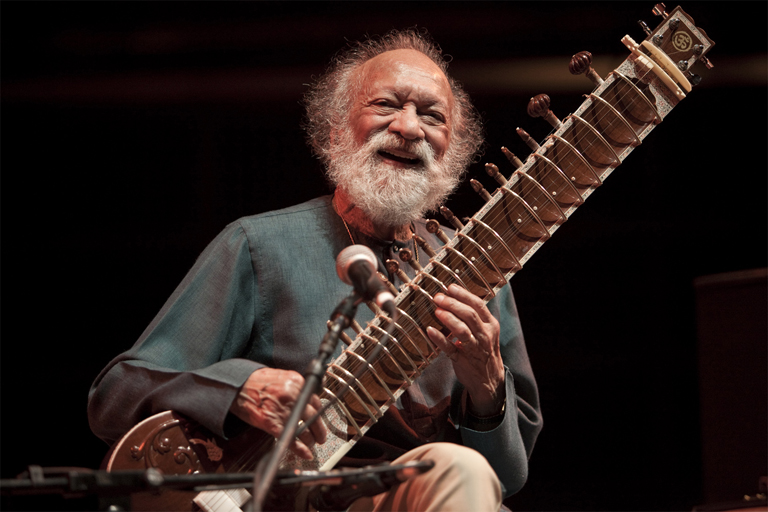

Pandit Ravi Shankar | Courtesy East Meets West Music | Photo by Jitendra Arya

Pandit Ravi Shankar | Courtesy East Meets West Music | Photo by Jitendra Arya -

Satyajit Ray and a young Pandit Ravi Shankar | Couresy East Meets West Music

Satyajit Ray and a young Pandit Ravi Shankar | Couresy East Meets West Music -

Pandit Ravi Shankar | Courtesy East Meets West Music | Photo by Michael Collapy

Pandit Ravi Shankar | Courtesy East Meets West Music | Photo by Michael Collapy -

Leela Naidu and Balraj Sahni in a still from Anuradha, directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Leela Naidu and Balraj Sahni in a still from Anuradha, directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Shubha Mudgal analyzes Pandit Ravi Shankar’s contribution to Indian film music

The involvement of stalwarts of Hindustani classical music in the sphere of Indian film music is by no means uncommon. The early history of film music in India is replete with names of great exponents of classical music who also chose to explore the then new medium of film to enhance their fortunes and prospects. Some chose to work as sessions musicians where they remained largely anonymous but prolific. Others worked as composers, arrangers or assistants to music directors. Many approached film music merely as a steady source of income, abandoning it for a full time involvement with classical music at the first possible opportunity. Pandit Ravi Shankar on the other hand remained resolutely anchored to classical music, permitting himself relatively few but remarkable associations with film music. And perhaps it was this very distance from films and film music that prompted Satyajit Ray to invite Shankar to compose for his all time classic Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road) in the 1950s. In an interview with Bert Cardullo quoted in the latter’s book World Directors in Dialogue: Conversations on Cinema Ray states: “I thought instead that it would be a good idea to work with someone like him, who would be able to introduce a fresh approach— quite unlike conventional Bengali film composers at the time”. So, what unconventional and fresh approach did Pandit Ravi Shankar finally bring to the music of Pather Panchali?

The melodic line hummed by Shankar for Ray at a meeting in Calcutta found approval with the director who described it as “a folk tune of sorts” and “just right for Pather Panchali“. Indeed, the melody has the simplicity often associated with folk tunes, with a certain charm that is universally accessible. But it is a simplicity that can as easily be transformed into a statement of poignance or great joy or devastating grief. In Pather Panchali, Shankar arrives at these transformations using different methods and devices. He sometimes uses a change in timbre and tone by employing a different instrument, for example, the flute. On other occasions he alters the pace of the melody, or places it over a rhythmic line (watch this, from after 11 minutes and 27 seconds), giving it a persona that is almost playful. In doing so, he gives the viewer and the listener a melody that is original and yet connected with heritage, which has the simplicity that makes one hum it quite easily, but also has the ability to be extended, elaborated and ornamented in a variety of expressive ways. It is in that sense, most certainly the work of a master. A clichéd use of the same device finds common usage in Hindi films, where a popular song is slowed down to what in filmi parlance is termed a “sad version”. Unlike the “happy” and “sad” versions so unimaginatively used in Hindi films, the variations on the Pather Panchali theme are brilliantly created by Shankar to be employed with matching brilliance by Ray in the film.

A significant aspect of the magic of Shankar’s score for Ray’s Apu Trilogy lies in the fact that it also features the great sitariya as a performer. A good composition can be rendered ineffectual or even wrecked by a performer who does not match up to the strength of the composer. Here, the composer was also a performer whose brilliance touched the hearts of music lovers across the world. The radiant tone of his sitar, the krintan that made his swaras flutter like a butterfly, and the virtuosic nature of his playing are all an unmistakable part of the music he created for the trilogy.

Songs rendered by playback singers are a unique aspect of Indian films, and Shankar’s songs for films such as Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s award winning Anuradha (1960) and Gulzar sahab‘s Meera (1979) are a grand testimony both to his brilliance as a composer and to his versatility. Not surprisingly, the unmistakable impact of classical music is particularly evident in four tracks from Anuradha, all recorded in the pristine voice of Lata Mangeshkar.

Saanware Saanware based on Raag Bhairavi could well pass off as a “bandish ki thumri” were it not for the arrangement and heavy orchestration accompanying it. However, even in the arrangement, the impact of classical music remains constant and is illustrated by elements such as the exquisite use of the sarangi to bring in the song, the teentaal theka maintained on the tabla, and the sawaal-jawaab (call and response) like sequences between Mangeshkar’s taans and the string section.

Shankar uses the sarangi in almost all the songs for Anuradha, and once again there is a brief but delicious sarangi alaap that launches the wistful Kaise Din Beete, Kaise Beeti Ratiyaan. The term hai is commonly used to connote various emotions— shock, fear, lament, grief and more. Often, the usage of the term is loud and noisy but in this composition, the prefix of hai is used with surprising delicacy. The effect is magical and like a yearning sigh. Composed as a brief cascade of descending swaras, it is sung effortlessly by Mangeshkar but with an expressiveness that remains unmatched to date. If there is one single drawback in this near perfect track, it is in the melodic composition of the last stanza where the lines “Barkhaa na bhaaye, badra naa sohe” are too high, even for Mangeshkar’s voice with its amazing range.

In the arrangement for the sparkling Jaane Kaise Sapanon Mein Kho Gayi Ankhiyaan, there is ample evidence of Shankar’s deep involvement with rhythm. While the song itself coasts along smoothly on a regular rhythm, the rhythm for the musical interludes and introduction is arranged with a series of jumps, tihais, breaks, accents and punctuations that convey the excitement of youthful romance. In direct contrast is the rhythm arrangement for Hai Re Woh Din Kyun Naa Aye which follows in a regular seven matra cycle, conveying a sense of lament heightened by Mangeshkar’s flawless rendition of the song.

There are, of course, several other scores to study and analyse— Gandhi, Meera, Chappaqua, Charly and more. And as one studies, there are many questions that crop up in one’s mind. Questions that perhaps Panditji himself would have answered with an impish smile. But now, one will have to seek the answers in the music that he leaves behind as legacy.

Songs of the Little Road

OpinionDecember 2012

By Shubha Mudgal

By Shubha Mudgal

Shubha Mudgal is one of India's best known exponents of Hindustani classical music. She specializes in the genres of Khayal, Thumri and Dadra. She has also experimented with popular and fusion music. She is a recipient of the Padma Shri, one of the country's highest civilian awards. She has also received the National Film Award for Best Non-Feature Film Music Direction for the documentary Amrit Beej and the Gold Plaque for Special Achievement in Music at the Chicago International Film Festival for her music in the feature film Dance of the Wind. (Photo by Nitin Joshi)