-

Himalaya Palace in 2006, when 3 screens showed Indian films | © Danny Robinson (CC-BY-SA)

Himalaya Palace in 2006, when 3 screens showed Indian films | © Danny Robinson (CC-BY-SA) -

Himalaya Palace in 2007 | © Jonas Sauciunas

Himalaya Palace in 2007 | © Jonas Sauciunas -

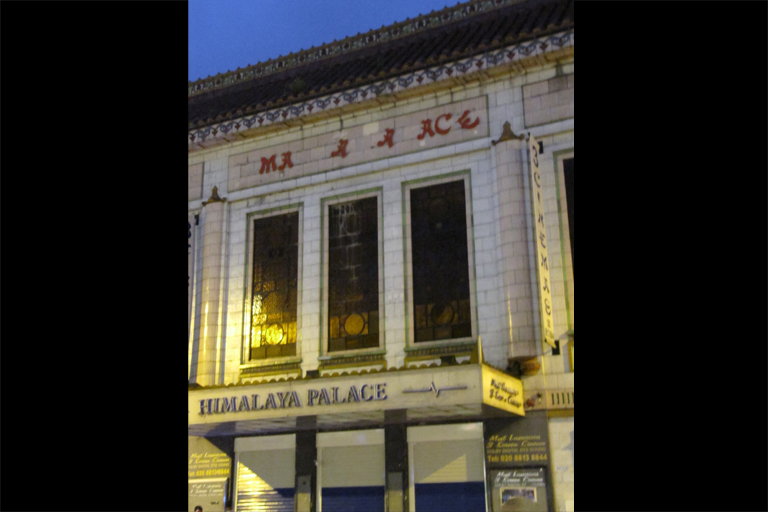

Facade of Himalaya Palace Aug 2011, months after it shut down | © Pragya Tiwari

Facade of Himalaya Palace Aug 2011, months after it shut down | © Pragya Tiwari -

Poster for classic Hindi film 'Himmatwala' probably shown as part of their classics' screenings in 2010 | © Pragya Tiwari

Poster for classic Hindi film 'Himmatwala' probably shown as part of their classics' screenings in 2010 | © Pragya Tiwari -

Poster for a 2010 release on the Himalaya Palace billboard in 2011, months after it shut down | © Pragya Tiwari

Poster for a 2010 release on the Himalaya Palace billboard in 2011, months after it shut down | © Pragya Tiwari -

The Himalaya Palace in 2012, converted into a shopping centre (The building is a Grade II listed heritage building) | © Alan Murray Rust (CC-BY-SA)

The Himalaya Palace in 2012, converted into a shopping centre (The building is a Grade II listed heritage building) | © Alan Murray Rust (CC-BY-SA) -

Agha Pan and Music shop | © Pragya Tiwari

Agha Pan and Music shop | © Pragya Tiwari -

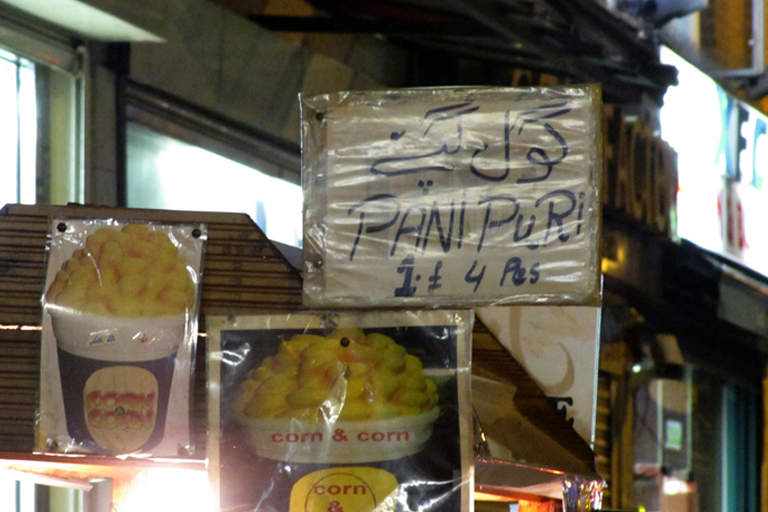

Authentic streetside pani-puris at 1 sterling pound for 4 pieces | © Pragya Tiwari

Authentic streetside pani-puris at 1 sterling pound for 4 pieces | © Pragya Tiwari -

Bikanervala, a popular Indian food giant offers a deal at almost-Indian prices | © Pragya Tiwari

Bikanervala, a popular Indian food giant offers a deal at almost-Indian prices | © Pragya Tiwari -

Business as usual at an Indian restaurant | © Pragya Tiwari

Business as usual at an Indian restaurant | © Pragya Tiwari -

Busy Southall High Street | © Jonas Sauciunas

Busy Southall High Street | © Jonas Sauciunas -

Chaudhry's TKC, a popular eating house established in 1965 | © Pragya Tiwari

Chaudhry's TKC, a popular eating house established in 1965 | © Pragya Tiwari -

The erstwhile Company Bagh, the open-air beer garden of Glassy Junction | © Pragya Tiwari

The erstwhile Company Bagh, the open-air beer garden of Glassy Junction | © Pragya Tiwari -

Gifto's, another popular eating house across the road from TKC also established mid 1960 | © Pragya Tiwari

Gifto's, another popular eating house across the road from TKC also established mid 1960 | © Pragya Tiwari -

Olive Morris at a Black Panther rally, Courtesy Remembering Olive Collective (CC-BY-SA)

Olive Morris at a Black Panther rally, Courtesy Remembering Olive Collective (CC-BY-SA) -

Glassy Junction | © Pragya Tiwari

Glassy Junction | © Pragya Tiwari -

Glassy Junction | © Basher Eyre (CC-BY-SA)

Glassy Junction | © Basher Eyre (CC-BY-SA) -

Indian manufactured alcohol on sale at a grocers | © Pragya Tiwari

Indian manufactured alcohol on sale at a grocers | © Pragya Tiwari -

Indian Textiles in a shop display | © Jonas Sauciunas

Indian Textiles in a shop display | © Jonas Sauciunas -

Indian Bride Barbies on sale | © Tupinambah

Indian Bride Barbies on sale | © Tupinambah -

Hindu idols for sale in the High Street | © Jonas Sauciunas

Hindu idols for sale in the High Street | © Jonas Sauciunas -

Baisakhi Celebration Parade in Southall 1988 | © Mark Charnock

Baisakhi Celebration Parade in Southall 1988 | © Mark Charnock -

Langar in a gurdwara in Southall | © Tupinambeh

Langar in a gurdwara in Southall | © Tupinambeh -

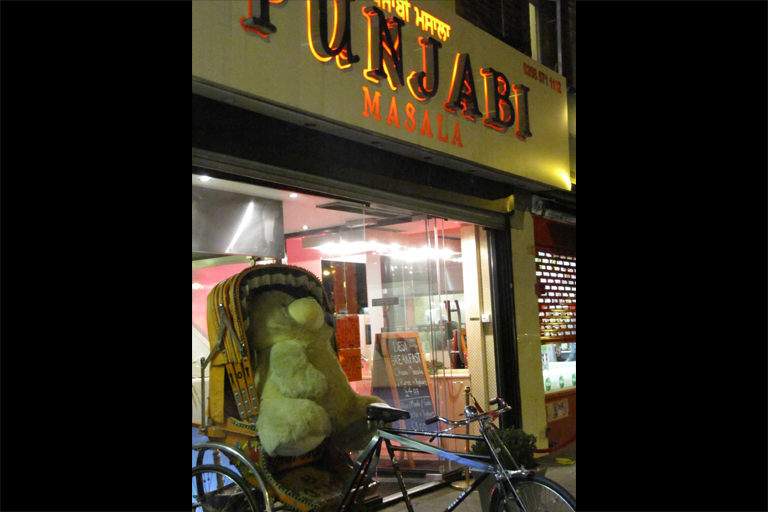

Kitch rickshaw decoration outside a restaurant | (c) Pragya Tiwari

Kitch rickshaw decoration outside a restaurant | (c) Pragya Tiwari -

Old boys making the most of the sun | © Jonas Sauciunas

Old boys making the most of the sun | © Jonas Sauciunas -

Roadside Jalebis | © Tupinambah

Roadside Jalebis | © Tupinambah -

Ramgarhia Sabha Sikh temple | © David Hagwood (CC-BY-SA)

Ramgarhia Sabha Sikh temple | © David Hagwood (CC-BY-SA) -

Punjab National Bank, a nationalised Indian Bank | © Pragya Tiwari

Punjab National Bank, a nationalised Indian Bank | © Pragya Tiwari -

Pavement on the Broadway | © Danny Robinson (CC-BY-SA)

Pavement on the Broadway | © Danny Robinson (CC-BY-SA) -

Savouries and sweets | © Pragya Tiwari

Savouries and sweets | © Pragya Tiwari -

Selling rakhees on the streets | © Pragya Tiwari

Selling rakhees on the streets | © Pragya Tiwari -

Sher-e-Punjab market in the Broadway | © Basher Eyre (CC-BY-SA)

Sher-e-Punjab market in the Broadway | © Basher Eyre (CC-BY-SA) -

Shooting for a Hindi film on the streets in Southall | © Jonas Sauciunas

Shooting for a Hindi film on the streets in Southall | © Jonas Sauciunas -

Southall station sign | © Júlio Reis (CC-BY-SA)

Southall station sign | © Júlio Reis (CC-BY-SA) -

Suman Marriage Bureau | © Pragya Tiwari

Suman Marriage Bureau | © Pragya Tiwari -

Vishwa Hindu Mandir | © Danny Robinson (CC-BY-SA)

Vishwa Hindu Mandir | © Danny Robinson (CC-BY-SA) -

Variety entertainment poster | © Pragya Tiwari

Variety entertainment poster | © Pragya Tiwari -

Blair Peach (Public Domain)

Blair Peach (Public Domain)

Farrukh Dhondy reconstructs the history of Indian and Pakistani immigrants in London, through the story of one cinema hall

The first time I went to the Liberty Cinema, at some forgotten date in the early seventies, was not to watch a film but for an afternoon political rally. One of the conspicuous buildings in Southall (Pronounced ‘South-Hall’ by its residents and ‘Sudhhll’ by the snooty English), West London, with its ludicrous Chinese-dragon facade and its rather fetching art deco interior, it sits between the two shopping hubs of the Punjabi suburb.

Almost opposite it is a park and the main road proceeds over a railway bridge under which is Southall station with a connection to West London’s termini. It descends the railway bridge, passes a very famous pub with figures of men with sashed turbans stuck on the exterior called Glassy Junction and pronounced ‘Gill-arsyy Junkshin’ and runs a quarter of a mile to the High Street.

If one ignores the simplicity of the Victorian and Edwardian worker’s-cottage-terrace architecture this High Street with its garish signs selling sweetmeats and DVDs could be a market street in Ludhiana. The large groceries of the High Street flow onto the pavements with, to Britain, exotic fruit and vegetables: karella, kuddhoo, methi, different kinds of mirch, bunches of dhania and cardboard boxes of the various varieties of mangoes when in season.

The other road from the cinema leads to another shopping centre with equally sumptuous supermarkets for groceries, fineries and jewellery, past a tiny park where the old men, whom as a passer-by I always think of as Sikh veterans of the Second World War, gather of an afternoon. Then on to various gurdwaras and out of the suburb to the M4, a motorway that connects London to Bristol.

The Liberty cinema was the venue for the first of several rallies I attended. It was, when not showing films, the hub of political agitation, meetings and rallies invariably called by one of the Indian Workers’ Associations. If you guessed that there were three or more factions of this organisation, owing allegiance and sending money to the Congress, the Communist Party of India, to the Communist party of India (Marxist) and to the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) you can give yourself a pat on the back. That these organisations hated each other and have now, with the integration of the new generations of Southall into British life and away from strictly Punjabi factional politics, melted away without significant numbers or significance, is also true.

I went with others to Southall from London proper—or improper considering the nature of the districts in which we lived—as a pamphleteer, agitator and member of other immigrant organisations such as the British Black Panther Movement and Race Today.

The one mass meeting held in the Liberty Cinema in the late seventies was to protest the death of a young man called Gurdip Singh Chaggar, fatally assaulted, it was alleged and never proved, by three skinhead youths. At the time the leading neo-fascist party of Britain was called the National Front. One of its leaders John Kingsley Read, commenting on the killing of Chaggar publicly pronounced “One down— a million to go.”

All of Southall, as other parts of the country, came alive and demanded action and justice from the police and government. The militant factions of Asian youth, that marched, declared Southall a no-go area for racists. It was 1976.

Three years later, in April 1979, the National Front decided to hold a rally during the general election of that year in the town hall in Southall. It was a stunt to get attention as they had no members in the area but wanted to make a gesture of propagandist defiance by holding their meeting in the heart of an immigrant community.

Their main platform was the repatriation of immigrants, and the police who gave them permission to hold a meeting and a march on those streets in an Asian suburb were well aware of the certain provocation and threat to civil order this posed.

The cops were out in force, with vans parked in several side streets, and patrols and contingents numbering hundreds with riot shields and vizored helmets lining the High Street to hold back the counter demonstration of anti-fascists.

A school-teacher called Blair Peach joined this counter-demonstration under the banner of the National Union of Teachers, a professional union to which I earning my living at the time as a schoolteacher belonged. I knew Peach as he was an activist in the Union and we met in left-wing organisations. At the time the male sartorial fashion was flared trousers and shoulder-length hair with perhaps a growth of beard in imitation of the rock stars of the day. It is embarrassing to recall how both of us looked like that!

The police with riot shields fought off the young Asian crowds who attempted to stop the National Front members who sought the protection of vans and buses in their passage to the Town Hall. All hell broke loose and by the late afternoon several street battles had been fought and very many young Asians and others arrested.

At around 6 pm, when things were quieter, Blair was attempting to make his way away from the troubled High Street, taking a short cut through the terraced Edwardian houses of Southall, when he passed a police patrol getting into their van.

One copper left his van, ran up to Peach unprovoked, according to witnesses, and bludgeoned him with his baton. Peach fell to the ground and was assisted by Asian bystanders who witnessed the assault from their garden. They called the ambulance but Blair died from the cracked skull and injuries to his brain an hour or so later.

The newspapers denounced our anti-racist demonstrations instead of taking the police and the National Front to task for this needless provocation and mass civil disturbance in which three people had their skulls cracked open and many others suffered injuries.

The murder of Blair Peach was the singular tragedy and injustice of this street battle. My colleagues and I went to a protest meeting again at the Liberty cinema. By then the hall was in a decrepit condition with the stuffing emerging from the split seats and the paint dull, with perhaps the smoke from cigarettes patrons lit up, ignoring the non-smoking signs. There was no heating as I remember. The rhetoric was brave enough.

The film that was showing at the time was called Baton Baton Mein starring Tina Munim, Pearl Padamsee and Amol Palekar. I recall reading the poster and thinking of the irony. An English person would read ‘baton’ not as ‘baathon’—‘conversation’ in Hindustani—but as the police’s bludgeoning weapon and ‘mein’ as the possessive pun in German. It was an idle thought and certainly one that hadn’t occurred to anyone else.

The demonstrations of the late seventies were symptoms of the incipient upward mobility and growing demands of the second generation of South Asians who form today, with their children, a third and even fourth generation of immigrants, 65 percent of the population of the suburb.

Those demonstrators in the late seventies were not going to accept any form of second-class status in British society and they were making it clear that those forces antagonistic to their presence would be met with the sort of retaliation that film heroes such as Amitabh Bachchan or Mithun Chakraborty would dish out in the potboilers produced in those days.

*

It was not always so. The Asian inhabitation of Southall began, so the legend goes, when a British officer of the former Raj who had returned to West London after Indian independence and set up a small factory—some say a bakery—invited the retired Sikh soldiers he knew to join him as workers in Southall.

The suburb is close to Heathrow airport which today uses Asian labour in various capacities, from lavatory attendants to baggage handlers, security guards and the staff of packaged-meal suppliers to airlines.

In the years between 1950 and the mid sixties Southall grew through the untrammelled, at the time legal, influx of the families, relatives and village neighbours of the dominantly Punjabi workers who arrived in Britain and took up these jobs which didn’t require any great familiarity with England, its culture or language.

The community built on itself, opening the small-trade shops of imported food and ‘native’ goods. It became a settlement, though never a ghetto, with the white population moving out and the Punjabis, from both sides of the Indo-Pak border but predominantly from Amritsar, Jullundur and Hoshiarpur, moving in and acquiring the relatively cheap terraced housing.

Of course there had been Indians in Britain before the 1950s. They were mostly from aristocratic and upwardly mobile families. Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Lord Sinha, Shapur Saklatvala and later Nehru, Jinnah and Gandhi had all passed through and made their mark.

But here now was the ex-peasantry of India, in Britain not to study and return to its leadership but to settle and work, mostly at the jobs that the British white working class had abandoned—‘shift work and shit work’—after the Second World War.

India was a newly independent country and was consciously searching for its identity. Indian film was now the lingua franca of the country. A pioneer of the industry Raj Kapoor was compellingly aware that what he was doing in telling his stories and portraying his characters on screen, or presenting Nargis and other actors with himself, was defining what an Indian is or should be. From Aag, Barsaat, Awara and right through his films of the sixties, Raj Kapoor is creating the new myths of what an Indian man is. The patriotism emerges in the songs:

“Mera joota hai Japani

Yeh patloon Inglistani,

Surr pey lal topi Russi

Phir bhi dil hai Hindustani… ”

It’s an anthem that recognises that India may not yet manufacture all the externals—the shoes, trousers, hats—but the heart that beats within…

And then the defining of the man with a simple heart caught up in the turmoil of modernity and conquering it with the simplicity of the Awara, the Shree 420 or of Raju who lives where the Ganges flows:

“Mera naam Raju,

Gharaana anaam

Behti hai Ganga

Jahan mera dhaam.”

The peasant, the wanderer is the generous heart of the new nation:

“Mehmaan jo hamara hota hein

Wo jaan sey pyara hota hein… ”

And it goes on to pronounce the mantra of survival of a country that knows itself as poor. Indians will survive by steely humility and not through materialism.

“Zyaada ki nahin laalach humko

Thodey mein guzaara hota hein… ”

The characters he creates, the lovable rogue, the bewildered villager wandering into the city with a Chaplin-like innocence and conquering the evils and complexity of city-slickers and their plots are an off-shoot of the Gandhian vision of spinning wheels and simplicity. Of course these mythical virtues exclude chastity or there’d be no scope for the seductiveness of Nargis.

The ideal is constructed on a nationalistic myth.

“Jahan hoton pey sachchayi hoti hein

Jahan dil mein safai rehti hein

Hum us desh key vaasi hein

Jis desh mein Ganga behti hai.”

One can be certain that, with some part of their minds, the children of the new republic were conscious that our lips were not constantly endowed with indelible truth or our hearts clean as the driven snow. Only the geography of the lyric was dead accurate: we did live in the country through which the Ganges flows.

Then there was Nargis who broke away from Raj and acted in Mehboob’s extravagant Mother India. If Raj defined the Indian man in that immediately post-independence decade, the years of the first Indian settlement of Southall, Nargis’s role harked back to the message of Krishna in the Mahabharat. She surrenders her son, who has turned to dacoity, for the sake of the greater truth. Her karma remains in the service of dharma.

Godliness is for Gods and however strong our self-image as created by the films of the fifties was, the nation should have realised that films were merely incarnate ideals and entertainment— and that’s how we liked them. If films allowed in too much reality they became ‘art’ and who needs to go to the cinema for that? We get enough of it at home!

*

The Himalaya Palace, the most recent name of the Liberty Cinema around which I have attempted a peripheral and deficient history of Southall, began life in 1912 showing silent British and American films. With the severe and relatively swift change in the demographic by the early sixties, the owners screened some Hindi films on weekends. It was renamed the Godeon, then altered to the Godina— perhaps to reflect in its first syllables a version of the Punjabi pronunciation of ‘Godeon’.

In 1972 it became the Liberty Cinema and by then it was London’s only Hindi picture palace. It was where I, with friends from bed-sitter central London, went to see Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeezah and Manmohan Desai’s Bhai Ho To Aisa. Both films were extremely popular though one noticed a distinct difference in the clientele. The Pakeezah audience were older men and very many women. The love story, the pathos and the nostalgia for even an enclosed Muslim haveli culture was evident.

The Manmohan Desai film, devoid of the classical grace of Pakeezah, was stuffed with stunts and imitations of the cheaper tricks of contemporary Hollywood. The outrageous plot, reminiscent of Marie Corelli’s bad nineteenth century novel Vendetta, gets the hero to fake his own death and reappear as an avenging dacoit to kill his brother who tried to kill him. The audience for Bhai Ho… was packed with young males and they followed the action with howls of approval and seemed silently willing to suspend their disbelief when faced with the absurdity of the plot.

*

In 1979 I gave up my steady job of teaching a South London school in order to write my fourth published and, I hoped, succeeding books. Writing didn’t immediately pay the bills so I farmed myself out as a ‘supply’ teacher, one that’s assigned to a school to cover the classes of teachers who are away through illness or other circumstance.

As it happened I was assigned to a girl’s school in Southall. I had to travel the fifteen miles from my home to the west of London each day, but the actual teaching was a surprise.

I had known and met the citizens of Southall in several capacities but they had all been men, young and old or they were the shy and retiring older ladies who were occasionally my hostesses when I visited some grandee of the Indian Workers’ Association or some activist on the Asian Left. They spoke in Punjabi accents and served tea and parathas and sarson ka saag.

Here in the girl’s school was a captive second or even two-and-a-half-th generation— daughters of some first generation immigrants or of their offspring who had been brought to England from the Punjab at a young age and had grown and married and sent their girls to school.

All the girls, 90 percent of them Asian, spoke in London English accents and some of the sixth form to whom I had to teach Keats and E. M. Forster (no, not Passage to India) had somehow, possibly from their British teachers, acquired middle class accents, a sort of preparation for a smooth entry into the professions. The statistics were telling. This predominantly Asian school got far better exam results than a hundred others in the boroughs around.

“So will you go to university?”

Six of the twelve would.

“And then will you return to Southall?”

They looked at each other. Where else would they go?

I knew what they meant. Southall was the world, they knew no other and they hadn’t come to terms with the fact that they were probably fated to be the first to break out of it.

“You never know, as in the Foster novel, you leave home, you fall in love and romance carries you away.”

They giggle.

“It happens all the time in the Hindi films doesn’t it?”

Yes, they admitted, it did and they loved Hindi films and I heard the yearning for the possibility in their answers. But they didn’t go to the Liberty cinema anymore even with their families. It was too rough and the cinema showed the sort of films that only boys like. Two or three of them illustrated the point by saying “dhishoom, dhishoom!”

And those who wouldn’t go to university even if they got good grades at A level? One said her father wanted her to join his estate agency, two of the others said they would be sent to college in the Punjab “where it was safe”.

My few weeks at the school were a snapshot of the advancing and turbulent culture. The girls would go home and speak Punjabi. In the playground I heard some of them swear like cockney troopers. Most of the girls in the school wouldn’t get to the sixth form. Those who didn’t would remain in Southall, probably marry and make families and homes there.

By the beginning of the eighties Southall was not just Little India, it had spread as those who could afford it. Those who had money through prosperous business on the central streets, or through the warehouses on the periphery, had moved outward to Hayes, away from central London, and to Greenford and Ealing, a mile or two towards it.

*

By the early eighties the Liberty had shut down and an enterprising businessman had bought it and set up a market of stalls. The enterprise was doomed. It was too far away from the main trading centres and market streets and the community had no preference, as may have been exercised in a pretentious white area of London, for shopping in an art deco converted interior over finding the cheapest bargain on the stalls of the High Street. The market didn’t last.

The coming of Channel 4 to national TV and the proliferation of Hindi films on video were the last sharp and decisive nails in the coffin of Southall cinema. Both of these happened in 1982. Channel 4 began showing classic Hindi films in ‘seasons’ of twelve each, with one or two new releases thrown in. It was free to air and as the Channel 4 executive responsible for choosing, buying, contracting, subtitling and transferring the films to transmittable media I gathered the statistics. 80 percent of Southall accessed our Indian film seasons. Hindi films were by that year on video anyway and the popularity of electronic media was beginning to kill the potential of cinema.

A couple of years into my job as a commissioning editor of Channel 4, I received a phone call from a fellow who identified himself as a young filmmaker who had to produce a short film to qualify as a director. Could he have one of my short stories set in Pune, India—and then—would I also write the script. He began to explain that he had no money and was asking me to give him my story and adapt it as a script for free. I thought it over and, out of the goodness of my hard heart, I agreed.

He said in the days to come that he was going to capture on camera the Indian milieu in Southall and I tried in vain to explain that Pune in Western India, on the Deccan Plateau, bore little resemblance to the British-Punjabi setting of Southall. He said he had reconnoitred the Liberty cinema and it was ‘perfect’. His team persuaded him that it was not.

I wrote the script and he shot the film in a mall cafe that doubled as Pune. It was his first film and he was, though very British, determined to reach out to the world as he did starting with filming in Southall and moving to more international climes and becoming, as Michael Winterbottom is, a famous director.

Michael may have seen the charm of the cinema hall that had fallen into desuetude, but couldn’t really stage a Pune tea cafe in it. It was derelict and worse.

British sentimentality and aesthetic nostalgia came to the rescue of the ruined setting, the beacon of different dreams in Southall. English Heritage, a national organisation that safeguards architectural treasures looked at the faux-Chinese exterior and the deco interior of the building and decided to spend £135,000 on its restoration.

In 2001 the building reopened as the Himalaya Palace with three screens devoted to Bollywood blockbusters. The theatre was now as swanky as anything in the West End with the added attraction of the restored architecture of George Coles who designed its present appearance in 1929.

Sitting in the Himalaya Palace to watch Singh is Kinng sometime in the first decade of this century was strange. My friends and I had gone for the experience of the deco theatre, to appreciate as well as be sardonically critical (to take the piss, to be truthful) of the film and then eat at our favourite restaurant— the Brilliant. The theatre was virtually empty. The film was of the genre of pure entertainment that more and more cynical Indian audiences, seeking the definition of their souls and roles from realms and dimensions other than filmistan, watch.

Why weren’t they watching this one? Three good reasons. Any number of video channels by then aired any Indian film you wanted, even the latest ones on some demand arrangement. Then, Southall is by most measures the largest DVD bootleg market for Hindi films in the known world. Perhaps the most important factor of all is that the young, from teenagers to people in the third of their Shakespearean seven ages, and perhaps even those in their fourth and fifth, watch American and British films. Less attention on the Hindi. They are in that limited sense bicultural.

The Himalaya Palace terminated business in 2010. Pass the site now and you find the plywood boards on the windows and signatures of graffiti artists on the walls.

The fortunes of the Himalaya Palace building with its ups and downs is not a metaphor for the progress of Southall which is a settlement that has, octopus-like, spread through West London and is a measure of the prosperity and mobility of the Asian community that converted this characteristic outlying limb of London into a muscular demonstration of the city’s global dimension and growth.

Indian cinema, while worshipping and pouring the money of unimaginative producers into blockbusters is fast evolving new genres of film that take observation of reality rather than the construction of myth as their raison d’etre. I am thinking of the films like Dhobi Ghat and Peepli Live or the more commercial but still observed films of Anurag Kashyap such as Gangs of Wasseypur. There are a growing number of others. These films have come to Britain but are, as of now, festival fare.

The coming year or two will determine whether Southall has a segment of its population that will begin to support their commercial exploitation in Britain. Will that lead to the Palace of the Himalayas having a new lease of life?

A small news clip covering the clash between the police and the predominantly asian community in Southall, London (April 1979)

The writer’s latest novel London Company has more on the times he writes about in this report and is now available in stores and online.

The Migrants and a Movie Hall

ArticleJanuary 2013

By Farrukh Dhondy

By Farrukh Dhondy

Farrukh Dhondy was born in Pune, educated there and then at Cambridge University. He worked in the UK as a teacher, and as a commissioning editor for Channel 4 TV, and as a writer of books, TV and screenplays. His books include The Bikini Murders, Adultery And Other Stories, Rumi: A New Translation, Poona Company and London Company. His screenplays include Bandit Queen, Split Wide Open, Jinnah, The Rising: Mangal Pandey, Kisna and Cover Story.