-

Opening titles from Rajkumar Santoshi's Damini (1993)

Opening titles from Rajkumar Santoshi's Damini (1993) -

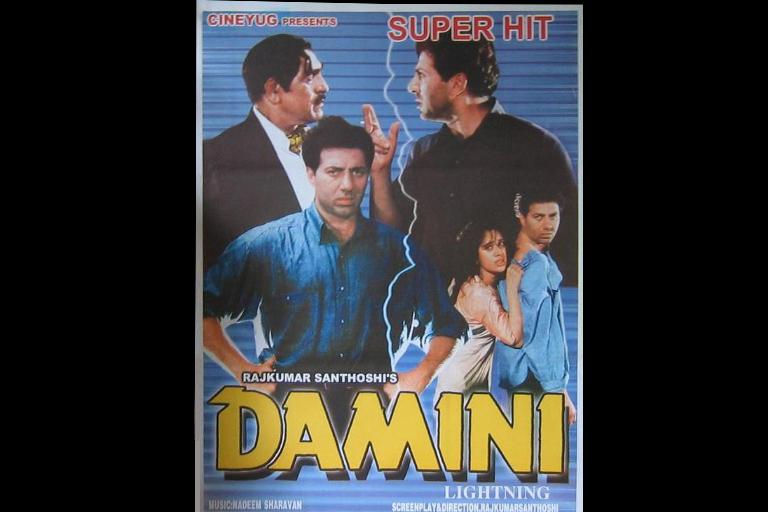

Poster for Damini

Poster for Damini -

Mahie Gill as Paro and Abhay Deol as Dev in Anurag Kashyap's Dev.D

Mahie Gill as Paro and Abhay Deol as Dev in Anurag Kashyap's Dev.D -

Kalki Koechlin as Chanda in Dev.D

Kalki Koechlin as Chanda in Dev.D

The Rape Kit

1.

Words make our world. Which is why she has become Nirbhaya, Amanat or Damini. While the first two names fall into the catch-all meaningless deep soundingness (such as every three-year-old Aryaman who has ever bumped into your knee) the name Damini made me pause.

It’s odd that in the frantic and embarrassing rechristening of the Delhi rape victim someone alighted on Damini. Will it stay Damini even now that the father of the young woman has named her in a foreign newspaper not liable under Indian laws? I don’t know yet.

In 1993 Damini came to us as filmmaker Rajkumar Santoshi’s compulsive truth teller who tries to seek justice for the housemaid she saw being raped by her brother-in-law and pals. Damini (Meenakshi Seshadri) was not raped herself. She was a stand-in for rape victims as much as Asha Parekh was a stand-in for young widows in Kati Patang. Damini’s crime was parrhesia. And she was punished with the loss of her marriage and comfortable life, imprisoned in a mental asylum, humiliated in court.

I re-watched Damini recently and was surprised by how much power it still held, in its set-piece courtroom drama, in Damini’s operatic breakdowns and in the moral dilemma that her husband Shekhar (Rishi Kapoor) faces. Will he stand up for the truth, for Damini, against the status quo evil of his family? To watch Damini’s lawyer’s big speech against the injustice of the courts is to understand why old Bollywood worked. No matter how we cheapen it by making it the stuff of our costume parties and the kitsch on our walls.

Words make our world. And we needed to go back to 1993 to find a heroine even vaguely for our times. New Bollywood has little space for rape. Made as it is by laddish types for laddish types, it largely has space for sex positive girl heroes, from a Chanda and a Paro to that bizarre creature played by Esha Deol in Yuva whose idea of jolly teasing of boyfriend is to cry: “I will tell your parents I’m pregnant”. They are fun, fearless, female types sprung wholly out of the wish-fulfilling loins of intelligent male writers. Look past the clutter of landscape, patois and cool dialogue (“permission lena chahiye” is the kind of amazing, hoot-worthy line that makes it hard to look past the clutter). Stripped down, what remains in New Bollywood are mostly narratives in which the leading ladies are hostage to the male protagonist’s multi-coloured compulsions whether in Wasseypur or Delhi or Bombay.

So we return to Damini where a woman’s absolute obsession with truth-telling drives the plot. While the same claim can’t be made for most movies of the 80s and the 90s this is what you will remember they had. A whole lot of rape. Clunky, gross, titillating and often ridiculous rape attempts featuring villains tugging at some woman’s sleeves and cackling. And if it was a successful attempt (usually the hero’s sister), you know the victim would promptly go kill herself.

As clunkily as it dealt with everything that makes us realism junkies wince today, it featured rape centrally. Unlike any movie from New Bollywood you can think of. Rape featured as acts of revenge, power-play and punishment, just as it is often in real life. It rarely was stranger rape of the kind that came as a many-headed monster careening in a bus on a winter night. It was an uncle, a brother-in-law, a neighbor, the rich dude from your village, your employer, your aunt by marriage’s creepy younger brother. Just as it is, most often, in real life.

In the last month, Bollywood stars too succumbed to that compulsive opinion-offering we are all susceptible to. Some of them have been quite chance pe dance in using the Delhi gang rape to promote their movies or themselves. Where else were they going to turn to express their opinions about rape though? Not in the new movies where the rural exists for colour and the urban for gloss. Just real life. And Damini.

2.

Here is a new party game. Start a conversation about rape or sexual assault and count the seconds till some swaggering man about town or concerned ladies-log bring up the word ‘repression’. What repression meant in another time, in a small town called Vienna, we won’t go to here. What it means to us in our party conversations, our Facebook status messages, is not about a very specific pathological condition. It is the imagined effect of not being allowed to do what we think we want to do. “Our society is so repressed, yaar.” This is a framework of understanding that anthropologist Saba Mahmood mocked (in quite another context) as a ‘hydraulic’ theory. The genius of Saba Mahmood is that she has seen the exact image that many of us unquestioningly carry around in our heads to explain all manner of human behaviour from rape to riot— hot steam escaping a too-tight vessel.

Words make our world. Half-baked Freud and this weird slippage from repression to pressure have done rather severe damage to our understanding of who we are. The hydraulic theory leaves us with some unquestioned beliefs. At the crudest level here is how it operates. Principals of colleges, police officials, politicians make pronouncements of rape as they see it. Pressure (short kurti, skirt, sleeveless blouse, urbanization, alienation, living in Bharat versus India, Vidya Balan, Poonam Pandey, Yo Yo Honey Singh) on Steam (male sexual desire) plus Time = Rape.

Study after study has shown us that there is no evidence to show that television causes violence or rape. Why do those who have listened to Honey Singh and are revolted by his songs assume that others will listen to those songs and be driven to rape? Did they worry about these things when Osian and every half-way ambitious film festival in the country screened Korean and Japanese cinema of eye-popping sadism and misogyny? Does misogyny only have a legitimate space in the complex spectrum of ‘high’ art? Is a misogynist necessarily a rapist? Does the possession of books by Bhagat Singh make us bomb-flinging seditionists?

Why are we then calling for bans or boycotts of Yo Yo Honey Singh? It is because some of us are consumed by apocalyptic visions of the world, of an India teetering on the edge of barbaric chaos, waiting for the nudge of a rap song or a skirt?

When I was younger I assumed that all men are of course potential rapists. At 20 I lay awake with the worry that someday I will be that paranoid mother who does not allow her husband to cuddle her daughters. Today, I’m less consumed by such ideas about men, even after reading the papers everyday. It must be my false consciousness.

Today, I’m more concerned about what the decent thing for me to do in a situation is. I do not want to be the principal who now insists that his women engineering students get permission from their parents before going on college trips. I do not want to be the politician insisting on video camera-wielding policemen in parks or overcoats for girls in Pondicherry. I do not want to be the parent preventing her daughter from being a clumsy, absent-minded creature if that is who she is. I do not want to be the government official or the khap panchayat member blaming cell phones for all ills.

I certainly do not want to be the person telling people what music to listen to. I do not want to assume that Yo Yo Honey Singh plus men equals rape or that Kill Bill plus women equals samurai murder. I do not want to sign a petition banning Yo Yo Honey Singh.

Not listening is certainly a legitimate and ethical way of going about expressing your displeasure. If you want to remain at the level of a consumer that is.

What a more robust, less fearful culture we would be if we responded otherwise. Thoughtful essays are great. Angry Facebook updates are great too. You can’t dance to a thoughtful essay or a Facebook update though. But wouldn’t it be so much better if we, in the tradition of the mushaira, the qawwali and YouTube loving Koreans, made our own damn responses to Yo Yo Honey Singh. We have nothing to lose but our Saturday evenings. Watch this space for my attempt.

TBIP Take

OpinionJanuary 2013

By Nisha Susan

By Nisha Susan

Nisha Susan is a writer and critic based in New Delhi. She was Features Editor at Tehelka magazine and has worked for several non-profits. Her short fiction has been published by Penguin and Zubaan and she's currently working on a novel and a book on Malayali nurses. Her expectations of cinema were permanently raised from watching pulp films as a three-year-old in her grandfather's village theatre.