-

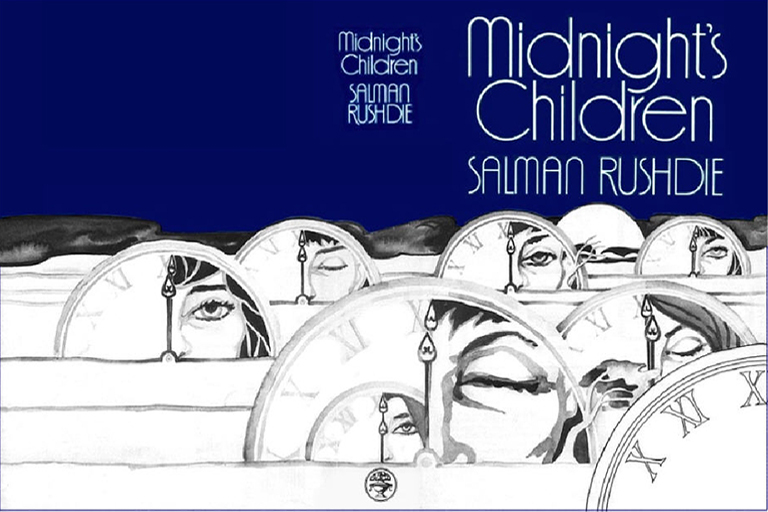

The Midnight's Children first 1981impression (Jonathan Cape publishers) book-cover

The Midnight's Children first 1981impression (Jonathan Cape publishers) book-cover -

Poster of Midnight's Children, the film (2012)

Poster of Midnight's Children, the film (2012) -

A still from Midnight's Children

A still from Midnight's Children -

A still from Midnight's Children

A still from Midnight's Children -

A still from Midnight's Children

A still from Midnight's Children -

A still from Beasts of the Southern Wild

A still from Beasts of the Southern Wild -

A still from Chariots of Fire

A still from Chariots of Fire -

Artwork with the original 1981 book cover and poster art from the 2012 film

Artwork with the original 1981 book cover and poster art from the 2012 film

Closing The Universe

On the 6th of May, 1954, a young doctor took a train from London to Oxford and ran a mile in 3 minutes, 59.4 seconds. He had trained for 8 years and given the Olympics a shot before he became the first man in recorded history to run a mile in less than four minutes. The record he made that day has had a strange history. Roger Bannister didn’t run much after that and spent his life as a self-effacing, highly successful neurologist. 46 days after he first did it, his arch rival John Landy ran the mile in 3 minutes 58 seconds. Sport records have an odd way of making commonplace the superhuman. Since Bannister over 1100 male runners have run the sub-four minute mile. His best has been lowered by 16 seconds. Schoolboys have done it and so have forty-year-olds. While no woman has yet broken four minutes for the mile, the current record stands at 4:12.56 by Svetlana Masterkova in 1996. Like in the Cole Porter song, birds, bees and educated fleas all have an eye on that mile.

Do those in the arts have similar burdens and compulsions of constant variation on elegant themes? Certainly there seems to be truth, universally acknowledged, in that Shakespeare can only be staged with radical political intervention and, preferably, in Croatian blank verse. On the other hand, no one seems to mind Austenian heroines come as they are, as they please. Filming Pride and Prejudice is treated like sponge cake— a classic challenge for the expert. The arts have a way of allowing the artist to amble along at the ten-minute mile if s/he has a respectful expression.

One might argue that the record-breaking athlete is powered by something more internal, not the gaze of the spectator. Even if this is taken as wholly true, the spectator of sports is powered by a desire for excellence, by that Daft Punk refrain for more. The spectator of the arts though is a tolerant creature, easily charmed and sometimes actively hostile to surprises. What would we do if Subodh Gupta stopped tossing stainless steel bartans in the air?

In 1981 a young Salman Rushdie gave the world a book of great beauty, of imaginative pleasures, a compulsive story. 1981 was the year of Chariots of Fire, the film that told the true story of two runners in the 1924 Olympics—Eric Lidell and Harold Abrahams, who incidentally was Bannister’s timekeeper when he ran the mile—but don’t be distracted. In the years since Midnight’s Children these are some of the things that have happened to the cinema and television viewer: Indiana Jones, E.T., The X Files, the Star Wars trilogy, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Twilight, the gargantuan Harry Potter empire, a whole lot of Almodovar, Terminator 2, Avatar, Rajinikanth, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Inception, Life of Pi and the internet. It is not clear that Deepa Mehta and Rushdie, as screenplay writer in the making of Midnight’s Children, have taken cognizance of the images already burnt into our brains.

Let’s not compare the beauty and strangeness of the five hundred-odd children who assemble in Saleem’s head from his tenth birthday, over 500 pages, with the poor sods who are extras in Midnight’s Children. By the time they started appearing (aside: what was that Bharatanatyam costume?) I had the uneasy feeling I was watching one of the trashier episodes of Heroes. Any minute Hayden Panettiere was going to turn up in Saleem’s room with her cheerleader costumer and a snotty (sorry, Saleem) attitude. When Satya Bhabha’s Saleem listed the ‘werewolf from Nilgiris’ people in the audience sniggered, so unthinkingly close (and yet so far) was it to the ‘assembling the A-team’ sequence of every caper movie. The pity of it was that, by staying in Saleem’s room, the movie didn’t give us the cheap thrills of showing us the gifts of the children either, in a way that this silly Hyundai ad does.

Midnight’s Children—the movie—ignores cinema audiences ready and ripe for the blurring of truth and magic. It’s an odd object, this movie— stiffly pedantic where the novel was fluidly cinematic. It ignores all the wild possibilities of flitting around the country (which the novel does bindaas from sentence to sentence) and when it does it is to show the tired old footage of Nehru making a tryst with destiny. Or to do embarrassingly saturated colour in a ‘Delhi slum’. Here I go, comparing it to the novel again. Ignore that. Let’s stay in cinema.

In 2009 a young woman called Lucy Alibar co-wrote the screenplay Beasts of the Southern Wild, an adaptation of her one-act play. In 2012 the movie has won everything in sight and been nominated for everything else. Its lead Quvenzhané Wallis is nine and the youngest actress to ever receive an Oscar nomination. Wallis plays Hushpuppy, a girl who lives in ‘Bathtub’, a southern Louisiana bayou community which is hit by a storm. Hushpuppy’s exteriors and interiors are full of the startling. She hangs with pigs and chihuahuas, lives in a shack of her own, a bell-ringing distance away from her father, and eats roast chickens whole. We hear the echoing heart beats of animals as she hears them. When we hear the noise of the approaching storm we could choose to think of this film as a response to Hurricane Katrina or just believe what Hushpuppy sees: the breaking of the polar icecaps and arrival of the aurochs. It’s a film that blooms magic realism at high speed like flowers in time-lapse photography. It allows, like Marquez’s Macondo, the space for both the ascension of Remedios the Beauty and the fear that the train is a frightful “kitchen dragging a village behind it”.

Rushdie once quoted an image of a dog barking in Saul Bellow’s The Dean’s December. “The central character, the Dean, Corde, hears a dog barking wildly somewhere. He imagines that the barking is the dog’s protest against the limit of dog experience. ‘For God’s sake,’ the dog is saying, ‘open the universe a little more!’ And because Bellow is, of course, not really talking about dogs, or not only about dogs, I have the feeling that the dog’s rage, and its desire is also mine, ours, everyone’s. ‘For God’s sake, open the universe a little more.’”

Midnight’s Children was Rushdie’s way of opening the universe. And like Bannister’s mile it lay open and luminous. This movie on the other hand has not even attempted to crack a window.

TBIP Take

OpinionFebruary 2013

By Nisha Susan

By Nisha Susan

Nisha Susan is a writer and critic based in New Delhi. She was Features Editor at Tehelka magazine and has worked for several non-profits. Her short fiction has been published by Penguin and Zubaan and she's currently working on a novel and a book on Malayali nurses. Her expectations of cinema were permanently raised from watching pulp films as a three-year-old in her grandfather's village theatre.