-

In Sivaji, the 'Vaaji Vaaji' song sequence Courtesy AVM Productions

In Sivaji, the 'Vaaji Vaaji' song sequence Courtesy AVM Productions -

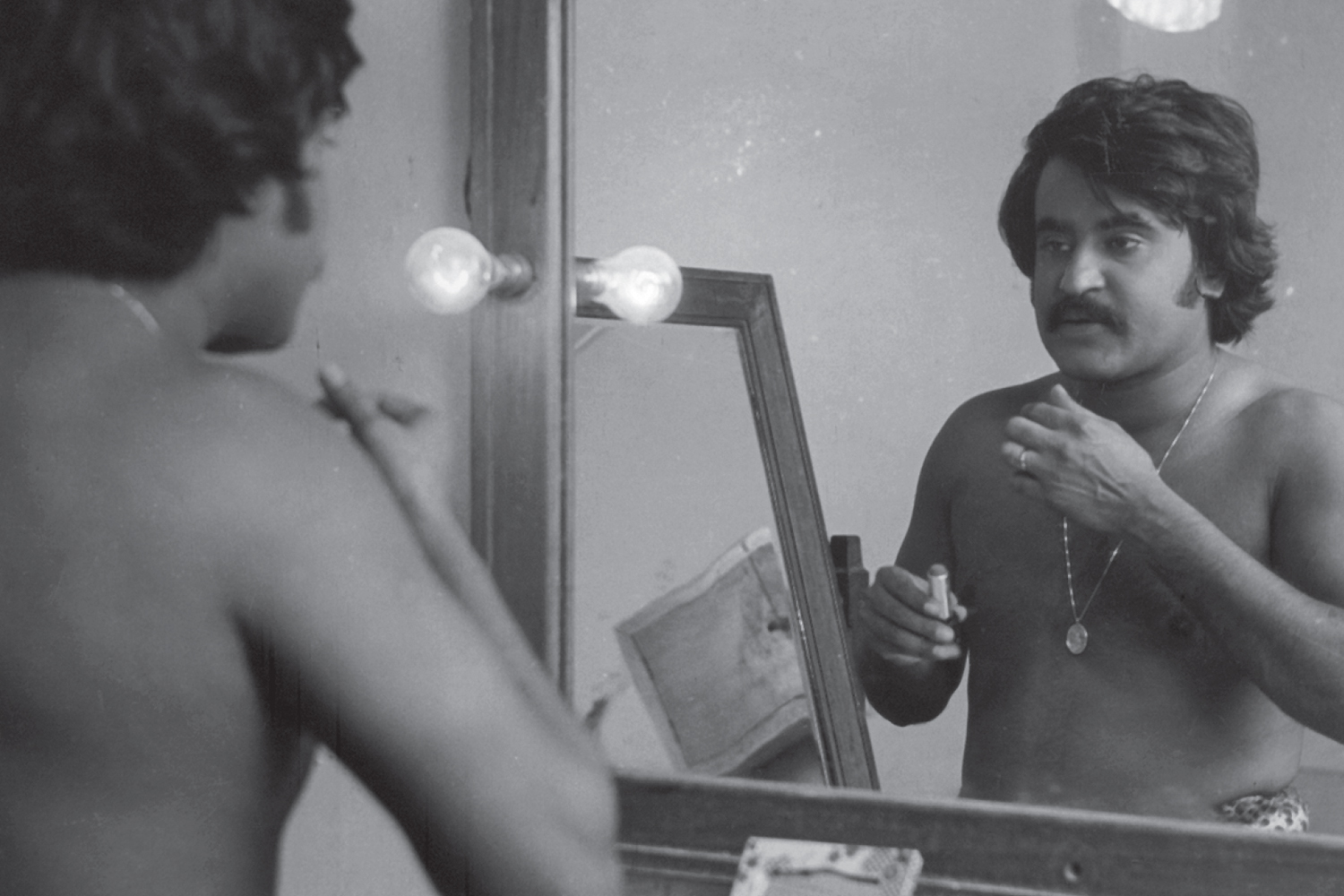

In the make-up room Courtesy E. Gnanaprakasam

In the make-up room Courtesy E. Gnanaprakasam -

Latha Rajinikanth visiting her husband on set Courtesy E. Gnanaprakasam

Latha Rajinikanth visiting her husband on set Courtesy E. Gnanaprakasam -

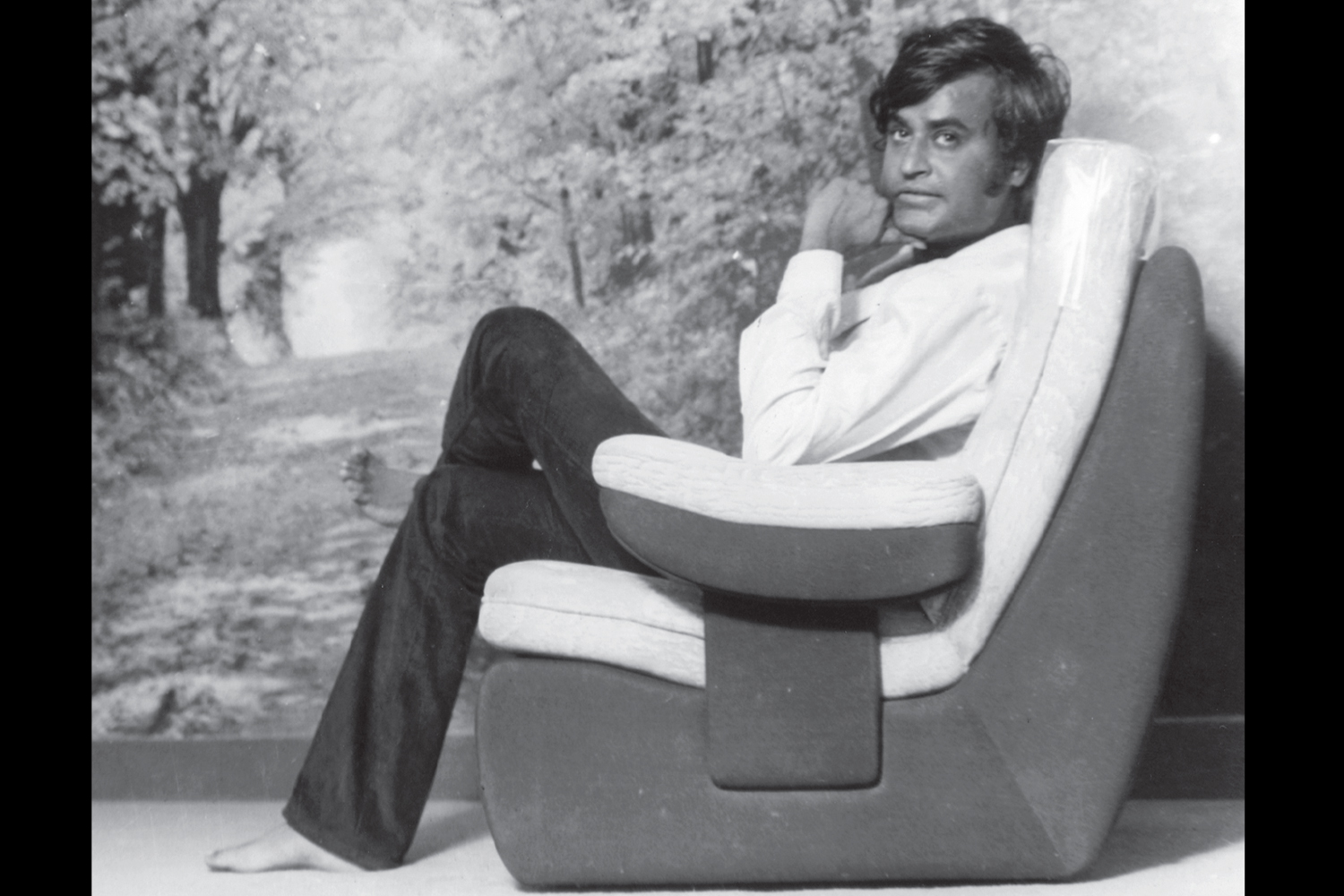

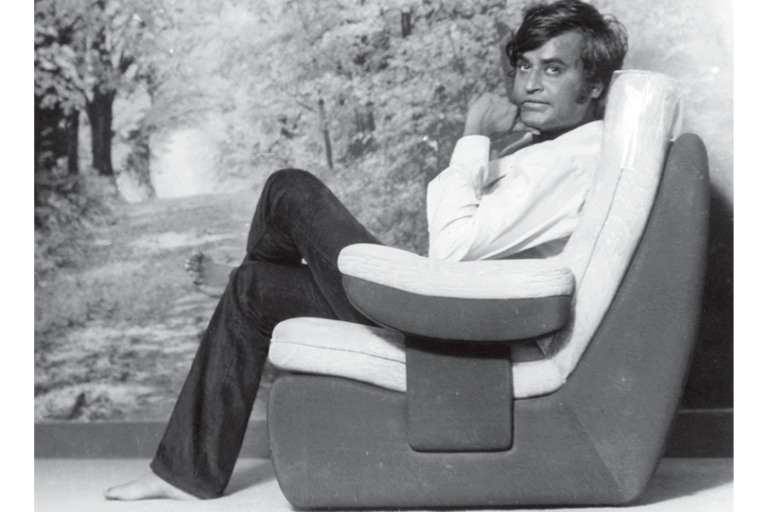

Posing for a photo shoot for a Tamil magazine Courtesy E. Gnanaprakasam

Posing for a photo shoot for a Tamil magazine Courtesy E. Gnanaprakasam -

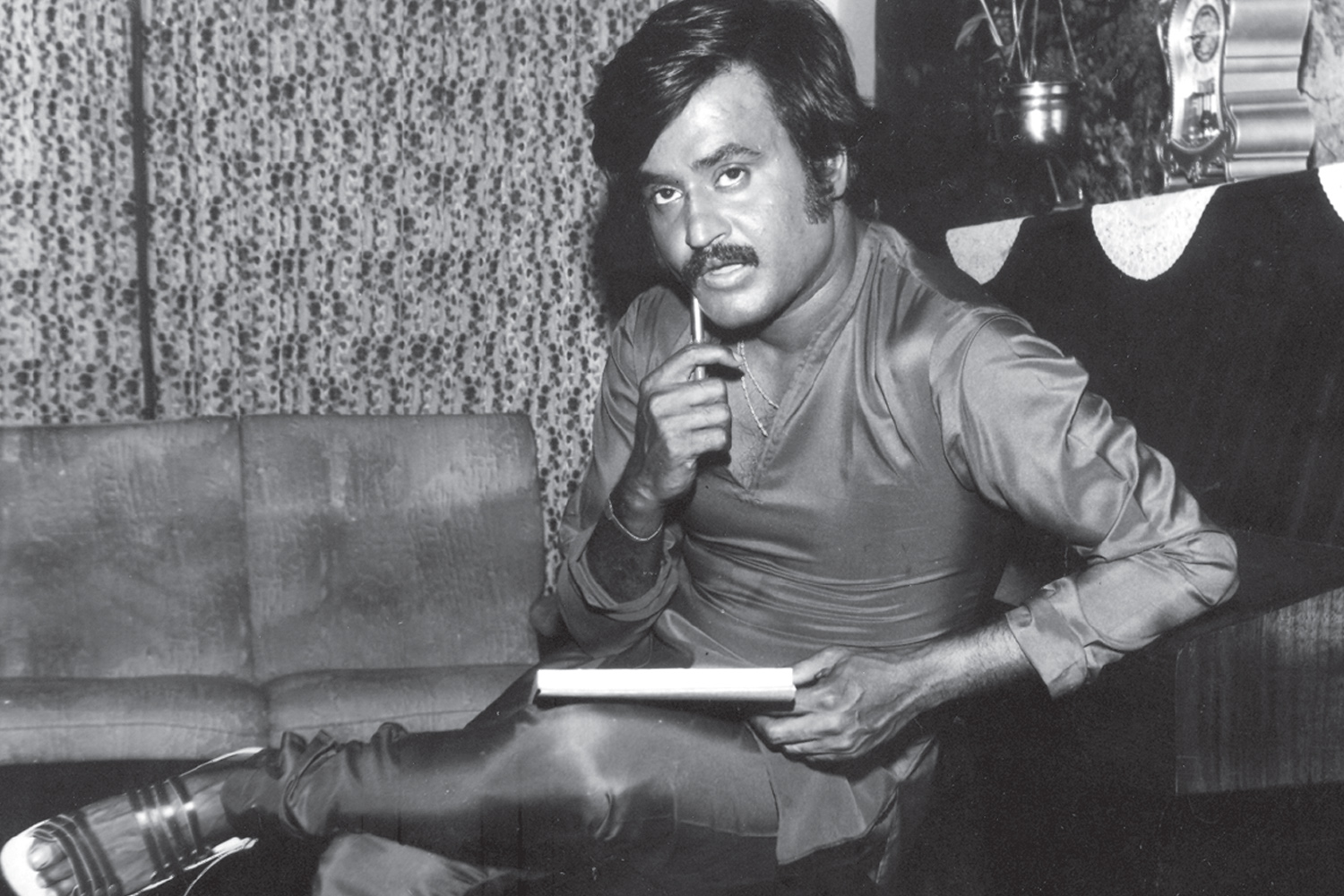

Rajinikanth sans moutstache, during the making of Thillu Mullu Courtesy E. Gnanaprakasam

Rajinikanth sans moutstache, during the making of Thillu Mullu Courtesy E. Gnanaprakasam -

Rajinikanth with Nagma in the 'Style Style Than' song in Baashha

Rajinikanth with Nagma in the 'Style Style Than' song in Baashha -

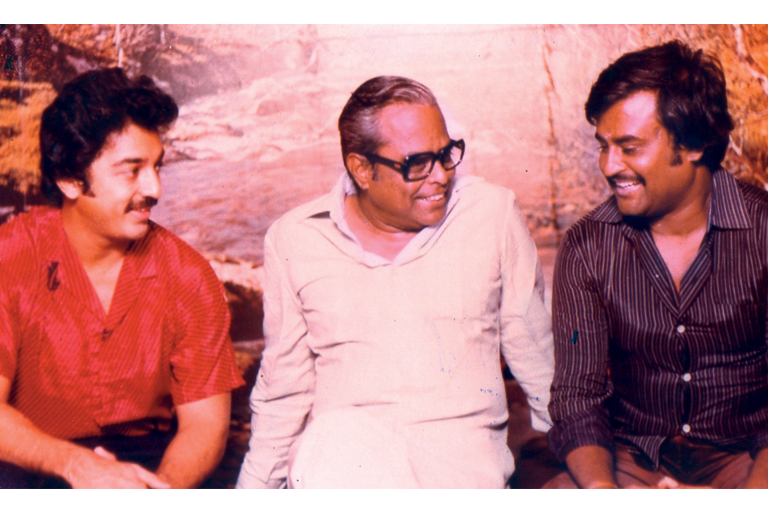

Sharing a lighter moment with Kamal Haasan and K. Balachander Courtesy Kavithalayaa Productions

Sharing a lighter moment with Kamal Haasan and K. Balachander Courtesy Kavithalayaa Productions -

With Hema Malini and Reena Roy in Andhaa Kanoon © Lakshmi Productions

With Hema Malini and Reena Roy in Andhaa Kanoon © Lakshmi Productions -

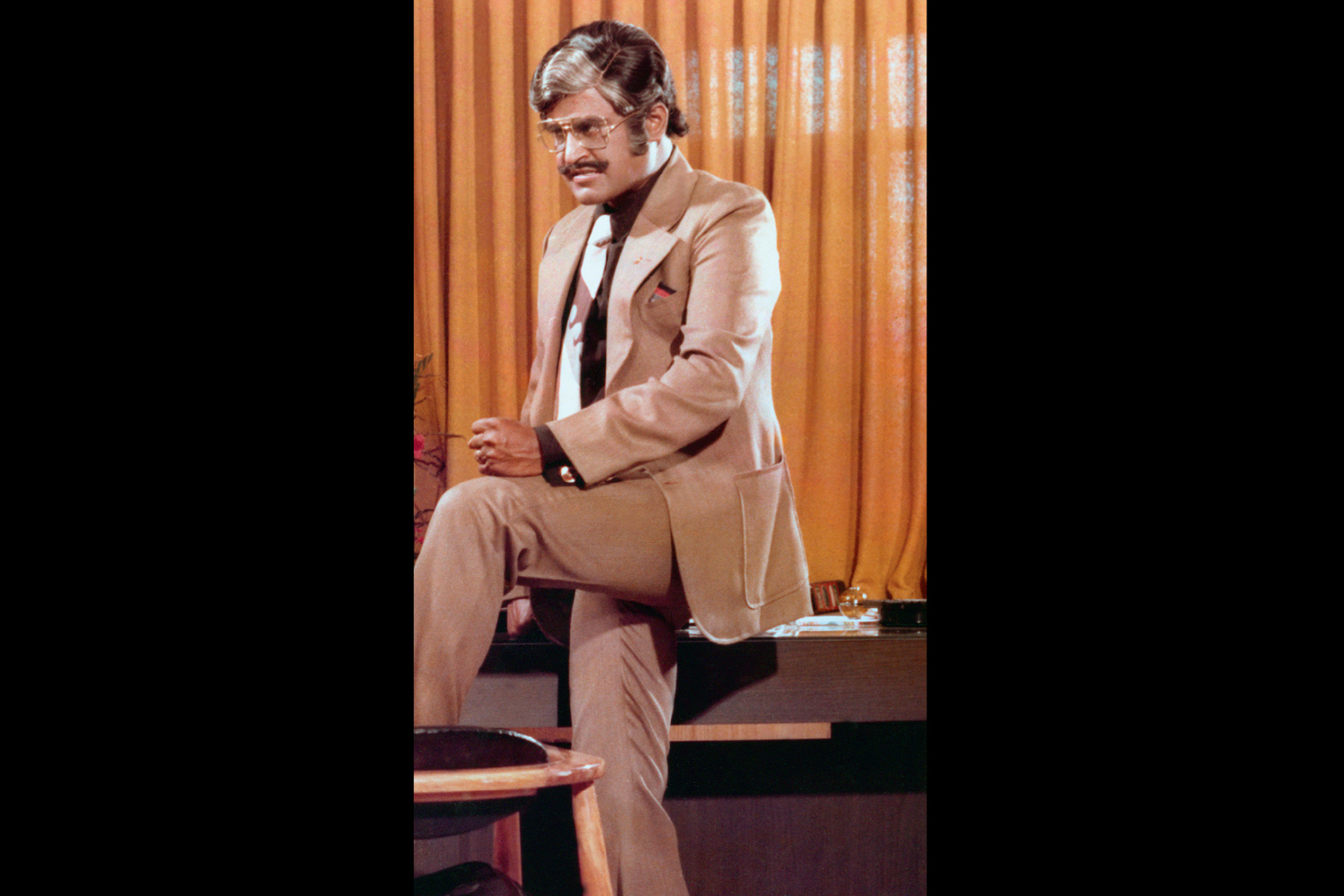

In Netrikkan Courtesy Kavithalayaa Productions

In Netrikkan Courtesy Kavithalayaa Productions -

In Geraftaar, © Raam Raj Kalamandir

In Geraftaar, © Raam Raj Kalamandir

Bus conductor, actor, deity, Rajinikanth has taken the meaning of Indian iconography to new heights. Here are three extracts from Rajinikanth: The Definitive Biography that give us a taste of his legend.

The Making of the ‘Superstar’

Bairavi opened on 2 June 1978. The man who orchestrated the film’s marketing campaign came from a tin-manufacturing background. Born and raised in Madras, ‘Kalaipuli’ (Tiger of the Arts) S. Dhanu used to excel in cultural activities like debates, elocution, poetry recitations and acting in his school days and won several intra and inter-school prizes for these. His family business was a cottage industry named Subramaniam Sheet Metal Works that specialized in supplying tin containers to snuff powder manufacturers. Dhanu joined the business right after completing his schooling. Soon, because of what he describes as his ‘thirst for the arts’, he got into the business of re-releasing old films that ran in morning shows. One of the first such was K.S. Gopalakrishnan’s 1962 film Sharada, starring Vijayakumari and S.S. Rajendran. Dhanu printed fresh posters for the film featuring a weeping Vijayakumari touching a pair of slippers; this was clearly aimed at the female audience, and triggered off a marketing campaign that outstripped the film’s original release publicity. The posters also had captions speculating on Vijayakumari’s fate. Dhanu released the film in 1974 at six Madras locations. The campaign paid off and the rerun ran to full houses. Dhanu then re-released film after old film with similar campaigns and they all worked at the box office. The clever part of this was that Dhanu had realized that in an era before home video and multi-channel television (the state-run Doordarshan available in Madras was a single channel with limited hours of broadcasting, begun in 1975), the audience with an appetite for older films had no source of getting them save for reruns. Dhanu even picked up, for a song as it were, films that had flopped on initial release; he would print posters focusing on interesting elements from the plot, and these became hits upon re-release.

Bairavi was the first new film that Dhanu acquired for release. “Our publicity covered the entire city,” says Dhanu. “I put up a 40-foot cutout of Rajinikanth at Plaza theatre. As soon as I set it up, the city corporation officials asked me to take it down.” Unfazed, Dhanu got an influential friend to call up the corporation commissioner and explain that he was a young man trying to grow in the business. The commissioner’s main concern was that the cutout was unstable and might fall on unsuspecting passers-by and traffic. Dhanu agreed to reinforce the cutout and it remained, lording it over one of Madras’s busiest thoroughfares. Apart from this, Dhanu printed posters proclaiming Rajinikanth as “Superstar”. “The publicity caught on like wildfire across Tamil Nadu,” says Dhanu. The posters were larger than the normal six-sheet ones. They featured Rajinikanth engaging with a snake, standing with a whip, carrying a goat on his shoulders and so on. “All of Madras was stunned and the cinemas were bursting with people,” recalls Dhanu. “From the time I saw a still from the film, I realized that it was a Rajini that nobody had seen before. MGR and Sivaji have done many films, but that particular still did justice to Rajini in a way that no picture has ever done for any star since. And that’s why I called him Superstar.”

Rajinikanth, writer and producer Panju Arunachalam and others in their group travelled from cinema to cinema to gauge audience reactions. “That’s when Rajinikanth asked who the distributor was,” says Dhanu. “And that’s when he came and saw me for the very first time, wearing a rose-colour banian and black trousers. ‘Fantastic publicity, beautiful publicity,’ he said. He hugged me tight. The Rajini I saw that day is still the same today.” The next day, however, Rajinikanth sent writer/producer Kalaignanam and director Bhaskar to Dhanu with the message that when huge stars like MGR and Sivaji Ganesan continued to exist, it didn’t feel right to be called Superstar— could the publicity be toned down? Dhanu’s response was to print another set of posters that said “The Greatest Superstar Rajinikanth in Bairavi”. The new posters were sent to Rajinikanth’s hometown Bangalore and the film was a massive hit there too.

Hum, and fitting in with Bollywood

DeepaSahi has vivid memories about the Hum shoot. She came to know about the existence of an actor called Rajinikanth only when she signed Hum. “I didn’t know before about him, because in the ’90s the North and South were very divided,” she says. “So the North Indian people knew very little about South Indian cinema, except for those films like Swayamvaram (Own Choice, 1972) that were brought for festivals. One never knew about the mainstream cinema there.” Sahi was born in Dehradun and studied at the National School of Drama in New Delhi.Even after the shoot began, Sahi wasn’t aware of Rajinikanth’s stature in the south. “I didn’t know for a very long time,” says Sahi. “I had no clue that he was the Superstar and his market price was around (I don’t know exactly) three times what Mr. Bachchan’s market price was. I didn’t know that I was so privileged to be working with the Superstar. And I found him to be a lovely, innocent person.” Sahi’s very first scene for Hum, during the film’s Ooty schedule, was nerve-wracking for her. She had to deliver a one-and-a-half-page-long lecture to veteran actor Kader Khan, who plays a general, with Bachchan, Rajinikanth and Govinda standing behind her. “It was my first commercial venture and I was horrified. I was given the dialogue in the morning. I said, ‘Look at these stars standing behind me!’” The shot was done in one take, however, and Sahi says that all the experienced stars around her were very supportive. “I found Rajinikanth to be a very sweet person who is very modest,” she says. “He would never join us for the revelries after pack-up. After the shoot everybody would freshen up and then gather in Mr. Bachchan’s room. But he would never ever join us. He was very shy and quiet.” Sahi recalls that Rajinikanth would sit alone in his room and open a fresh bottle of Johnnie Walker, one of the most expensive blended Scotch whiskies in the world; he would have a couple of drinks and then give the bottle away to a unit hand, and open a new bottle the next evening. “It was his only gesture that pointed to his wealth—because he is not at all a show-off or an extravagant guy,” says Sahi. “For me what that gesture meant is that it’s like pinching yourself to say— Is all this true?”

Sahi would talk to Rajinikanth a lot without really realizing that he was a superstar in the south. She had seen a couple of his southern films and appreciated his style and noted some gambling scenes he had done. During the film’s Mauritius schedule, Sahi wanted to go gambling with Rajinikanth to see how he gambled in real life. ‘We all went to the casino and he had no idea how to play blackjack or roulette!’ she remembers. “But the fact is he was so lucky that he would always win. He would just place a bet and would win. He was just doing it for the fun of it—and suddenly there was this huge pile of money he had generated. The fighters who were with us in the unit, they were all losing like crazy. They all came and said, ‘Rajini Sir, we have lost.’ And he said, ‘Take take take,’ and gave away all the money to them. They hadn’t even asked him to. In a stroke he gave it all away. And it wasn’t a small amount.” During the shoot, slowly, Sahi drew the reclusive Superstar out and got to know him better. “One day he was telling me, ‘I don’t know if you know that I was a bus conductor before this,’” she recalls. “I said I’d heard. He said, ‘God has been so kind to me and I have so much money. I have a tennis court and I don’t know how to play tennis. I have a swimming pool and I don’t know how to swim.’” There was a scene in Hum where Rajinikanth had to rescue Sahi from drowning, but he didn’t know how to swim. “He was constantly, diligently there though his double was doing the shot,” she says. Rajinikanth eventually talked to Sahi about Latha. Sahi says, “He was very, very proud of this lady he had married. He was very proud that she was educated and spoke very good English.” She says that during the shoot, she didn’t really know the protocol and hence would ask Rajinikanth and Bachchan to give her cues for her scenes with them, even if they were not in the shot. Normally, in the case of senior actors, if they are not in the frame, an assistant director gives the cue to the actor in the frame. Here, actors of the stature of Bachchan and Rajinikanth gave Sahi her cues themselves, a fact that left her impressed. “They would stand behind the camera and give me my cue, like any professional would. Only great people have that kind of modesty,” says Sahi. “Both Mr. Bachchan and Rajinikanth had no pretences of being stars.” Sahi also remembers that Rajinikanth had to go away during the shoot to attend the charitable weddings sponsored by him and held at the Raghavendra Kalyana Mandapam, of several indigent couples. “Rajinikanth is somebody who you never forget,” she says. “I’ve never forgotten my meeting him and working with him, because he was so unique in his reactions. The modesty and the humbleness— it was not a put-on. As an actor you can see it if somebody puts it on. People do these things. But not him. It was completely genuine.”

How Muthu became the “Titanic of the art theatres” in Japan

In 1996, Kandaswamy was in Singapore’s Little India district at the Mohammed Mustafa shopping centre, every Indian tourist’s haven, and was choosing some DVDs when he noticed three Japanese standing next to him and conversing in their language. Kandaswamy didn’t know any Japanese but got curious because every thirty seconds the word “Rajinikanth” came up in their conversation. Interest piqued, Kandaswamy inched closer to the Japanese to find out exactly what they were referring to. Not knowing the language, he couldn’t follow a word. The Japanese now noticed Kandaswamy edging closer and looked at him with suspicion. “After three minutes and ten mentions of Rajinikanth, I couldn’t stand it any longer,” says Kandaswamy. He offered to help if they were looking for something related to the Indian Superstar. Kandaswamy did not introduce himself as a producer. The Japanese took him seriously and told him that they were looking for four films of Rajinikanth’s; among them was Muthu. Then Kandaswamy took them to a nearby restaurant to understand their fascination with Rajinikanth.

“God shows you an opportunity, it’s up to you to grab it,” says Kandaswamy. One of the Japanese that Kandaswamy met on that fateful day in Singapore was Jun Edoki, a film critic. Edoki took the DVD of Muthu back to Tokyo and watched it with his wife. “It was absolutely fascinating— even without subtitles,” remembers Edoki. “We became addicted to the point where we had to see at least part of the film at least once a day.” Edoki became obsessed with the idea of getting Muthu a theatrical release in Japan. He took the film around to distributors until Atsushi Ichikawa consented to release it via his distribution company Xanadeux. But the rights had to be secured first. Xanadeux wanted to secure Muthu’s distribution rights for Japan for five years for a one-off fee without any box office profit percentage, if any, going back to Kavithalayaa. Kandaswamy was in a quandary. He had no idea what to ask for as a fair price as there was no precedent. He didn’t want to discuss the matter within the industry in Chennai (the name of the city had changed from Madras in 1996) for obvious reasons. It was up to him to take the decision. So he called Tokyo and asked them to name a price. They were taken aback as they were used to dealing with Hollywood and its prices and legalese. Kandaswamy was keen to explore this new, unknown and exciting market. Similarly, the Japanese were keen to try out releasing an Indian film in their market. They liked the film and believed it would do well, but the price was something both parties couldn’t arrive at. Kandaswamy made up his mind and took a call. “I said, one dollar. Price, one dollar. Can you believe this?” he says. “They were shocked, they thought I was joking.”

Kandaswamy made them promise that if Muthu did well, they would take all the future Indian films from Kavithalayaa for Japanese distribution. The Japanese agreed and the film was released in Japan in 1998 as Muthu, Odori Maharaja (Muthu, The Dancing Maharaja). Japan was suffering from a crippling recession at the time. Japan’s economy had shrunk 0.7 per cent for the financial year that ended on 31 March 1998, the first time the country had experienced negative growth since 1974. The yen had fallen to an eight-year low against the dollar, and consumers weren’t spending as much as they used to. The cinema is usually a cheap source of entertainment, and Muthu’s air of happiness and full-on entertainment came at exactly the right time for the country. Kandaswamy says that in 1998, movie ticket prices in Japan were amongst the highest in the world at $15, but he was insistent that ticket prices not be reduced just because the film was Indian. Shinya Aoki, editor of a Japanese film journal, says, “Indian films are filled with the classical entertainment that movies used to offer.” Miyuki Shinogi, who was a twenty-year-old college student when Muthu released, agrees. She saw Muthu after reading a rave review. “That was it— I was hooked for life,” says Shinogi. “Muthu had everything a movie fan could ask for, from dancing and singing to love scenes and tears. Most of all, it made me feel good.” The film was a remarkable success with more than a million Japanese queuing up at the turnstiles to watch it. At the Cinema Rise theatre located in Tokyo’s Shibuya locality alone, Muthu played for twenty-three weeks and attracted 127,000 punters, netting $1.7 million, easily the cinema’s biggest hit of the year. “It was the Titanic of the art theatres,” says Ichikawa.

The distributor had employed a shrewd marketing strategy that included distribution of flyers that read: “Forget about the recession. Forget about the millennium. Get rid of your worries. This is the first page of a pleasant dream that will continue for the rest of your life.” Another flyer said: “Starring Superstar Rajinikanth ‘Muthu’, Meena and Elephants!” Upon Kandaswamy’s suggestion, Rajinikanth was billed as the Indian Jackie Chan and was promoted across Japan thus, feeding off the Hong Kong star’s immense popularity in the country. Kandaswamy and Ichikawa also followed the maxim that nothing quite sells like a pretty face and flew the actress Meena over to Japan. She made a surprise appearance on stage immediately after the first show of Muthu in one of the bigger theatres. The actress was armed with three lines in Japanese that she spoke before an appreciative audience: “I love Japan. I love the Japanese people. Just see my film three times.” Kandaswamy says, “And that’s what the Japanese did. They saw the film three times.” According to Kandaswamy, the Japanese people’s dress and food habits changed after Muthu, and some people began wearing salwar kameez and consuming masala dosas. He says that Muthu’s socio-cultural impact on Japan extended to Bollywood dance schools springing up all over the country. The Japanese brewery Godo Shusei also cashed in on the trend, using Indian dancers to replicate a dance from Muthu in a commercial for their alcoholic drink Chu-Hi. Even though the agreed price for the Muthu rights was $1, Ichikawa generously paid Kavithalayaa much more than that, following the success of Muthu at the Japanese box office.

Excerpted from Rajinikanth: The Definitive Biography by Naman Ramachandran, published by Penguin Books India, Viking (Penguin India) Rs 699. You can purchase the book here

Cover Image: Rajinikanth in Apoorva Raagangal, © Kalakendra Films

S-U-P-E-R-S-T-A-R

ArticleMarch 2013

By Naman Ramachandran

By Naman Ramachandran

Naman Ramachandran, 40, is the London based author of 'Lights, Camera, Masala: Making Movies in Mumbai' and 'Rajinikanth: The Definitive Biography'. He is a film critic with 'Sight & Sound', and works as a journalist with 'Variety' and 'Cineuropa'. He has contributed entries to the books 'The Rough Guide To Film' and 'Movies: From the Silent Classics of the Silver Screen to the Digital and 3-D Era'.