-

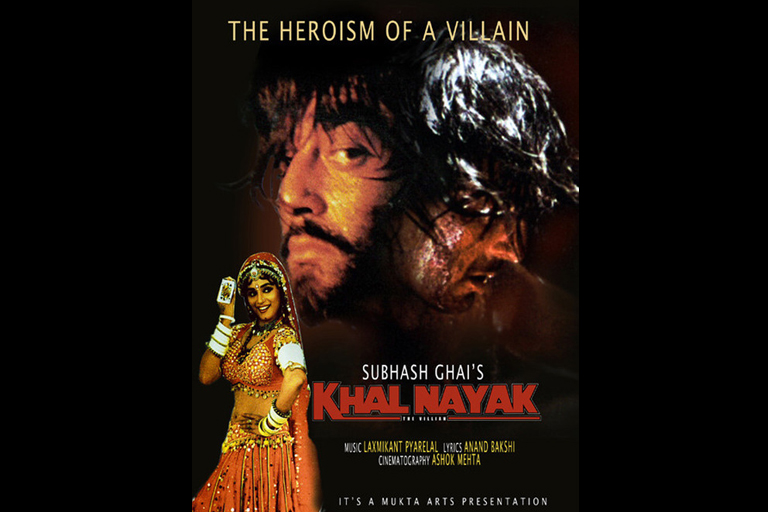

Poster of Khal Nayak

Poster of Khal Nayak -

Screenshot from Thaanedar

Screenshot from Thaanedar -

Still from Munnabhai M.B.B.S.

Still from Munnabhai M.B.B.S.

Dilip D’Souza on the lessons learnt from a two decade old case and why it is not really an accurate measure of law and justice in India

Let’s get a few things out of the way right at the start.

First, I have no sympathy for Sanjay Dutt. He violated the Arms Act in 1993 by his purchase and possession of a gun. He was arrested, tried and sentenced for that offence. Yes, the process took years. But that’s the way trials go. It took a few more years because Dutt appealed his sentence— which the Supreme Court has just upheld. That his time behind bars will result in losses for Bollywood, that other Bollywood stars are saddened by this news, is so much irrelevant gravy.

Second, let’s remember that Dutt was not found guilty of involvement in the bomb blasts of March 1993. The crime he has been convicted for is the possession of a deadly weapon. Period. Of course, a hundred others were found guilty for the blasts after a lengthy trial. The two prime accused, Tiger Memon and Dawood Ibrahim, were never even arrested, because they are “absconding”.

Third, Dutt is a rich and famous man. But being so, he only feeds the shibboleths we like to mouth even knowing how empty they are— “nobody is above the law”, and “the law will take its own course”: you know, corny stuff like that. He’s a scapegoat for the truth we simply don’t want to face up to and accept: the really powerful people in this country never get punished for their crimes. Never.

Those three done and dusted, here’s a short recap of what has brought Sanjay Dutt to where he is today and his curious fandango with a political party called Shiv Sena.

On March 12, 1993, a series of bombs went off in Bombay, killing over 250 people. While investigating that atrocity, the police arrested and questioned two film producers and distributors, Hanif Lakdawala (also referred to in various reports as Kadawala and Kandawala) and Samir Hingora. They told the police that they had sold an AK-56 assault rifle to Dutt.

This is why Dutt was arrested in April that year, why his home was searched, and why he was tried over the next dozen odd years.

Immediately after his arrest, the Shiv Sena’s leader, Bal Thackeray, declared a “ban” on his films and his party activists began disrupting their screening, especially the just-released and ironically-named Khal Nayak (Villain). The ban did not last long. In May, theatres resumed screening Khal Nayak. Naaz, on Lamington Road, did so with a sign in front acknowledging the “kind permission of Shri Balasaheb Thackeray.” Two years later, when Dutt was still behind bars and under trial, Thackeray attacked the CBI for being “vindictive” and keeping this “innocent young man” from a family of “patriotic Indians” in jail. There had, after all, been reports of visits by members of the Dutt family to Thackeray’s home. Thackeray was also worried about the loss—Rs 20 crore, he said—the film industry had suffered because of Dutt’s incarceration (as you can see, this trope of loss has a long pedigree). Soon after, Dutt was released on bail. From his jail cell, he went straight to Thackeray’s home to pay his respects. But the renewed bond was also temporary. In 2002, transcripts came to light of Dutt’s phone conversations with the gangster Chhota Shakeel. Thackeray now pronounced that the actor should not be defended “at any cost”.

But the fandango goes beyond this on-again, off-again game of footsie between the Dutt family and the late Sena supremo. Let’s go back to April 1993, and Hingora and Lakdawala. Here are two excerpts from news reports that month:

* “Top stars, MLAs got arms from Dawood” (Afternoon Despatch & Courier, April 12, 1993): “The Bombay Police have stumbled upon the names of several film personalities, MLAs and corporators, who owned illegal arms allegedly supplied by the underworld don, Dawood Ibrahim. The arms were either gifted by Dawood or sold to these persons at cheap rates. Interrogation of suspects… has thrown up names of film personalities such as Sanjay Dutt [and also] Shiv Sena MLA Madhukar Sarpotdar among nine politicians who acquired arms from the D-gang or his henchmen. The arms were mainly sophisticated revolvers.”

* “Sanjay Dutt arrested” (Indian Express, April 20, 1993): [Chief Minister Sharad Pawar told the Maharashtra Legislative Council that] “the suspect who named Sanjay [also] revealed several other names including that of Madhukar Sarpotdar. But we have not pressed charges against all.”

Writing in When Bombay Burned, the Times of India compendium of reports from the 1992-93 riots and blasts, the film critic Khalid Mohamed also recounted Pawar’s statement, adding: “Sarpotdar’s house was also not searched.”

Digest this: the same investigation—the very same one—that implicated Dutt, also implicated the prominent Shiv Sena politician Madhukar Sarpotdar, and in precisely the same way. No less than the head of the state government announced this, and in the state’s Assembly. Dutt has spent twenty years on trial for his offence. Sarpotdar? No charges under the Arms Act. Not even a search of his home.

Tell me about nobody being above the law.

There is more. On January 11, 1993—possibly at the height of the carnage during the Bombay riots, and two months before the blasts—the Army stopped a car that was roaming the city streets. Also from When Bombay Burned, here’s how journalists Clarence Fernandez and Naresh Fernandes reported this incident:

* “[T]he Army detained the Shiv Sena MLA Madhukar Sarpotdar in the troubled suburb of Nirmal Nagar late on Monday night and searched his car to find two revolvers and several other weapons… Travelling with Sarpotdar was his son Atul, carrying an unlicensed Spanish revolver. Though [Madhukar] Sarpotdar had a license for his gun, he too was breaking the law by carrying it during the riots. Also [with them] was one Anil Parab. [T]he police commissioner [refused] to indicate whether this man was the notorious gangster of the same name, the hitman of the Dawood gang.”

More to digest: Dutt’s offence was the illegal possession of a gun. Sarpotdar was also found in illegal possession of a gun. So it’s not just that Hingora and Lakdawala sold guns to both Dutt and Sarpotdar. No, Sarpotdar openly toted guns during the riots, and he was captured doing so by no less an authority than the Indian Army.

Yet Sarpotdar was never tried for this offence. Far from it. In February 1995, he ran for election as MLA and won. In 1996 and 1998, he ran for election to Parliament, winning both times. As if to drive home the irony, he stood and won from the same constituency that Sanjay Dutt’s father, Sunil Dutt, represented, that his sister now represents; more appalling than ironic to me personally, this is my constituency.

Forget being tried for violating our laws. For years after 1993, this man was actually making laws for us all. (For what it’s worth, the Dawood hitman Anil Parab himself was sentenced to life imprisonment for murder and other crimes, only weeks before Dutt was convicted).

What was that again about nobody being above the law?

There’s plenty more to say about Sarpotdar, including his shifty appearance before the Srikrishna Commission that inquired into the riots. Unfortunately, delving into all that will need a book, not just several hundred words on TBIP. Let’s leave it at this: Sarpotdar died in 2010, gone to the great riot in the sky without having spent a day in jail. That, and not Dutt’s sentence, is the really accurate measure of how justice and law operate in India.

What do we learn, looking back at the two decades Dutt has spent in trial? In no particular order, here are some of my takeaways.

* This has little to do with left or right wing politics. Instead, it has everything to do with power. The Shiv Sena has grown into an entity that nobody can touch; this is itself the fount of its power and appeal in Maharashtra. Thackeray is now gone, but his legacy is not one, but two equally virulent Senas. Sarpotdar is also gone, but his party is filled with others with similar records of public service.

* Thackeray actively drew prominent film stars into his fold. Ever wondered why Amitabh Bachchan, for example, has never suggested that Sarpotdar be treated as Dutt has been?

* Sanjay Dutt will do his time. I now don’t doubt that. But I have no illusions that this punishment will rid us of terrorism, or even slow it down. Because as long as we hide behind shibboleths, as long as we shy away from punishing the guilty whoever they are, we nurture terrorism.

In a song in Sanjay Dutt’s Lage Raho Munna Bhai, listen for these words aimed at a certain Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi: “Jhoot ka badhta jaye raj, O Bapu/ Apne hi ho gaye dhokebaaz.”

Think of it as an entirely telling epitaph for the fandango of Sanjay Dutt, circa 2013.

The Sanjay Dutt Fandango

OpinionMarch 2013

By Dilip D'Souza

By Dilip D'Souza

Dilip D’Souza trained in engineering at BITS Pilani and computer science at Brown University. After years in software, he began writing because that was where his passion lay. His writing has appeared in Caravan, The Hindustan Times, Fountain Ink, Seminar, the Washington Post, Salon, The Daily Beast and Newsweek, among many others. He has published four books (most recently, 'The Curious Case of Binayak Sen' and 'Roadrunner: An Indian Quest in America'), and has won several writing awards/fellowships, including the Outlook/Picador nonfiction prize, the Wolfson College (Cambridge) Press Fellowship and the 2012 Newsweek/Daily Beast Prize. He lives in Bombay with his wife Vibha, children Surabhi and Sahir. Their cats Cleo and Aziz rule.