-

A panoramic view of the interior of the Virginia Theatre (Photo Credit: David Jordan)

A panoramic view of the interior of the Virginia Theatre (Photo Credit: David Jordan) -

Attendees queuing up for Ebertfest

Attendees queuing up for Ebertfest -

The Virginia Theatre by day

The Virginia Theatre by day -

The Roger Ebert Boulevard (next to the Virginia theatre)

The Roger Ebert Boulevard (next to the Virginia theatre) -

Chaz Ebert

Chaz Ebert -

Chaz Ebert and Tilda Swinton

Chaz Ebert and Tilda Swinton -

Tilda Swinton

Tilda Swinton -

An Ebertfest Panel Discussion

An Ebertfest Panel Discussion -

The Virginia Theatre's front entrance at night

The Virginia Theatre's front entrance at night -

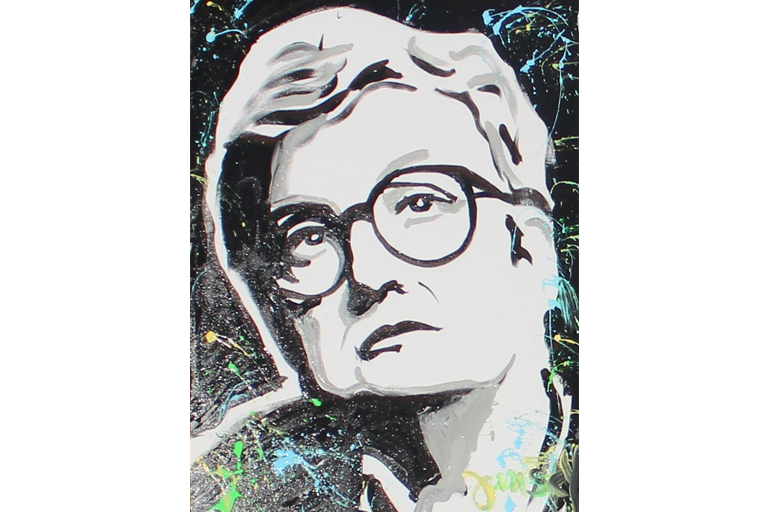

A painting of Roger Ebert by John Chansky

A painting of Roger Ebert by John Chansky

The 15th Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is the first to be held after the passing of its founder. Here is an account of the legacy of a man who was one of the most important voices on cinema ever

My only connection with film critic Roger Ebert is tenuous and insignificant— we both graduated from the same university: the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. However, his love for movies, and the fact that Urbana is also his hometown, has made that connection a tad more tangible. For 14 years Ebert visited his hometown every April to host a film festival which was originally known as Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival, then Roger Ebert’s Film Festival or simply: Ebertfest.

Like countless other cinephiles, my movie watching experience was incomplete if I did not Google ‘Ebert <insert movie name>’, after watching a film. Ebertfest was a chance for me to see the man whose exhilaration, disappointment, anger and anguish I had experienced only through his words. I wanted to know how he was in person. Would his disappointment with a movie be visible on his face? Would he furrow his eyebrows or shake his head? Was he as compassionate as his writing showed him to be? Was he really as enthusiastic about the movies as his monumental archive of writings would have us believe? How could he be? How could anyone be?

But, in my two years at the University, I did not attend Ebertfest even once. The first year I missed it because of my unrelenting academic workload and, in the second, because of my indolence. “Next year,” I had said. “Roger Ebert isn’t going anywhere.”

This year, in March, I finally decided to redeem my promise to myself and began making travel plans. On April 2, 15 days before the festival was scheduled to begin, Ebert wrote on his blog: “Last year, I wrote the most of my career, including 306 movie reviews, a blog post or two a week, and assorted other articles. I must slow down now, which is why I’m taking what I like to call ‘a leave of presence’.”

Did this mean he wouldn’t be at Ebertfest this year? I grew anxious at first but was relieved to read further on: “Ebertfest, my annual film festival, celebrating its 15th year, will continue at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, my alma mater and home town, April 17-21.” Things were in place. I would travel, watch films, watch Ebert watching those films. Maybe meet him even.

Two days later, Ebert was dead, at the age of 70, at the end of an 11 year long battle with cancer.

***

The 15th annual Ebertfest would go on as scheduled, announced the organizers. I did not cancel my plans to go.

On most days of the year, travelling from Denver (where I live) to Urbana takes five hours. Yet on this occasion it took me 37— thanks to multiple flight cancellations due to a turbulent snowstorm, and torrential rain. I was two days late for the festival. Two years too late for Ebert.

***

The venue, the Virginia Theatre, is located on the outskirts of the University town. It is quiet outside. There are a couple of tents selling refreshments and street lamps with small signs saying ‘Welcome to Roger Ebert’s Film Festival’, but the grandeur on the inside belies this modest exterior. Opened in 1921, the theatre is expansive— offering a seating capacity of more than 1500. The architecture is traditional and ornate and intricately painted canvas murals with extensive stenciling adorn the ceiling. Parts of the sidewall give way to small balconies, embellished by ornamental iron railings, and strategically placed lightning fixtures bathe the room in elegance.

Unlike other film festivals, Ebertfest does not accept submissions; the movies screened used to be personally selected by Ebert— particularly from amongst movies that had not got their due (hence the initial tag of ‘overlooked’ to the festival’s title, which was later changed as current and even unreleased films were chosen). Films at Ebertfest don’t compete for awards or deals from distribution companies. But the festival does give them one thing they have usually been denied— an appreciative audience.

This year, every movie at the festival is introduced by Ebert’s wife Chaz, followed by the filmmaker speaking for a while about the movie, and its making. As I take my seat for my first screening, I overhear a lady say, “Just look at the number of people present here. Today is Friday. How many people would have taken time off from work to be here?” Her friend replies: “I have met many people who have come from out of state.” The theatre is full.

The experience of Ebertfest is sacrosanct not just because it is hosted by a legendary movie critic, or because the festival truly celebrates the indie spirit, but also because of the people who support the festival— its audience. The movie watching experience is not just about the people on the screen, or the ones behind it, it is also about the people in front of it. The Ebertfest audience not only loves movies, it reveres them. The audience here is focused and participatory. At opportune moments during a film the laughs are raucous, the applause deafening and the sighs audible.

Every day at the festival begins with panel discussions held in one of the rooms of a student activity centre— the Illini Union. Once the panel discussion concludes, people head towards the Virginia Theatre, which is a mile-and-a-half away. For an audience that’s both eclectic and well informed, there are as many opinions as the number of people at the festival. “To me, Ebertfest is like Roger sitting in his living room and saying – ‘Hey! These are the movies that I really want you to see.’ In this case, his living room happens to be the Virginia Theatre. It’s a wonderful way to remember Roger’s taste; it’s a reminder of what good taste he had. Most film festivals don’t have that feeling of one person’s curatorial vision,” says Michael Phillips, the Chicago Tribune’s film critic.

This is the first time ever that Ebert is not at the festival. But his absence makes itself felt as grace, not melancholia. This has a lot to do with Chaz. When on stage, she reminisces about Roger Ebert with palpable joy and playful excitement. During one of her introductions she laughs about how, of late, she has become foolhardy; she speaks first and then thinks about what she has said: “And I am getting a lot and lot like my husband, who would spring a new surprise every day. He would just say anything. He was so enthusiastic about life that he didn’t care.” Chaz looks up at the ceiling here, smiles a little, shakes her head indulgently and says, “Roger, you’ve had a great influence on me.” And in this moment you feel, suddenly, that you are listening in on what is actually an intimate conversation; as though Ebert were actually listening to her. Chaz must feel this too. In a later speech, while speaking about how Ebert’s team of far-flung correspondents came together, she says, “As you know, if you write to him, he writes back.” She still uses the present tense for him.

The movies this year span many different genres, countries and themes but as, an Urbana local at the festival, who introduces himself only by his first name, Michael, notes: “It’s interesting, how a lot of movies at the festival deal with death.” In the Family, (directed by Patrick Wang), is about a homosexual couple and their six-year old child, and when one of the partners dies, it leaves the other to grapple with the meaning and purpose of his new solitary life. In Blancanieves (a Spanish film directed by Pablo Berger), an excellent silent movie, different characters deal with the deaths of their loved ones in different ways. In a particular disturbing-yet-heartbreaking scene, one character refuses to come to terms with the fact that his lover is no more and sleeps next to her dead body. And then there is Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1958 Japanese classic, The Ballad of Narayama, a bleak movie based on a Japanese folk legend that is about sending 70-year-olds to the mountains to die, especially in times of food scarcity, so that the younger generation has enough to eat. David Bordwell, a film historian at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, concludes his introductory note about this movie with these lines: “You probably know that this essay, which is in the [film festival’s] catalogue, is Roger’s last essay for his great movies series. And I am told by Nate Kohn [the festival director] that three weeks before his death, Roger asked that this movie be added to our schedule.” At the movie’s Q & A session, someone from the audience asks Bordwell: “After both watching the film and listening to the discussion I keep thinking about Roger, and his being 70, about the tension in the film between the sort of rage against the light and this acceptance and grace on the other side, and I wondered if there’s a possibility that there’s any message for us in the selection of this film, in the addition to this film, at the last minute, to the schedule.” Bordwell, who’s usually very articulate, struggles to answer this question. “Your points are quite valid, but I can’t go further,” he says. “Probably… he wanted us to think about that.” The grief of Ebert’s death and the joy of cinematic brilliance mingle bafflingly at the venue. Ebert, who was said in a 2010 Esquire profile by Chris Jones to be “dying in increments”, is no more, but he has left us handpicked movies that interpret his final departure; enable us to mourn it, as only art can.

That same night, after the last screening, I see a group of people crowding around something, taking pictures. It is close to midnight and the temperature has dropped to below zero. As I go closer I see an easel with a beautiful hand painted portrait of Roger Ebert in black and white. “I painted everything right here,” says artist John Chansky as he struggles to hold on to the canvas, against the ferocious wind. “There was no plan. I just wanted to come out and pay my respects, and wanted to say thank you for all the years of great entertainment.” People come forward to shake his hand but he can’t as it is soiled with paint. They bump their fists instead.

On an average, there is a gap of an hour or two between the films. In the intervals, most people prefer to lounge in or around the theatre, participating in question and answer sessions with filmmakers, chatting up other attendees or grabbing a quick lunch. They leave whatever they can on their seats— scarves, jackets, handkerchiefs, so the theatre never really feels empty. Most people tend to know one another here. If they don’t, they get to know each other during the festival. Not long after the first screening, faces begin to become familiar. They smile and acknowledge you. The ushers begin recognizing you too; the feeling of being a stranger dissipates quickly. “What I love the most about Ebertfest is that there are no parallel screenings and everything happens at one place. I went to a film festival at Vermont, and they had a total of 85 screenings at three to four venues; it felt very fragmented. On the contrary, Ebertfest has this community feel to it,” says Robin Shelly, who travels from New England every April to attend Ebertfest.

At Ebertfest, movies are not about glamour. There is no red carpet, no paparazzi hounding celebrities. At the last panel discussion of the festival I spot, sitting a few chairs away from me, in the last row, Academy Award winning actress Tilda Swinton, whose film Julia (directed by French filmmaker Erick Zonka, the film is in English and Spanish) was screened at the festival. She seems to be taking notes. It is a luxury for someone like her to watch movies without being hounded in the hallways. “Everybody comes here in this state of security, trust, and company and it’s a community,” she says. “And that’s the best thing about this film festival. He [Ebert] was, and he still is, great company. He knows that cinema is all about company, community, communication, and conversation between people.”

What further strengthens the feeling of community is the fact that people have come together here not only from the different states in the US, but also from different parts of the world— Canada, Norway, Mexico, Brazil and so many other countries. Krishna Shenoi, from Bangalore, India, came to Ebertfest for the first time two years ago, when he was 17 years old. The student and amateur filmmaker’s relationship with Ebert began in the way Ebert’s relationships with so many others began: he wrote to Ebert. “The second I would finish any movie, I would send it to him, because he would tell me something about the movie that would make me want to go out and make the next movie. He was very encouraging, more encouraging than even my parents or my best friends,” says Krishna. A few months ago, he created an animated tribute to Spielberg. Ebert loved it, wrote about it, which resulted in Krishna receiving a hand written reply from the filmmaker.

Everyone at the festival recounts a different Roger Ebert story. Some remember him as a generous colleague, as Phillips does: “My first time at the Cannes film festival, I had no idea what the hell I was doing – where to go, what line to get in, I was getting no sleep, I wasn’t eating regularly. And he just helped me out. He would tell me, ‘These are the people who will fix your tickets, these are the people who will arrange your interviews, you don’t have to go to this screening, don’t leave this event to go to that screening— you can catch it when it plays at 11 o’clock at night.’ A marvelous mentor figure for a lot of us.” Others recall his extraordinary enthusiasm for the movies. People discuss the times gone by. Times when Ebert was healthy. There used to be a midnight movie screening on Saturday. After this, film viewers would stay back to discuss the film at a local diner called Steak ‘n’ Shake. I hear that he would lead all these discussions, till well past 2 am, and be up for screenings early in the morning.

***

The golden days are over but golden moments are still up for grabs at every screening. Moments in which flickering images in a dark theatre stun us; exhilarate us; deliver us. Moments in which Ebert found himself. Moments in which we will continue to find Ebert. Because there is only so much death can take away.

Finding Ebert

ArticleApril 2013

By Tanul Thakur

By Tanul Thakur

Tanul Thakur graduated from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign with a degree in electrical engineering. He prefers watching movies alone and spends most of his free time in a local indie theatre scouting lesser known movies. He is based out of Fort Collins, Colorado.