-

Nargis - Image Courtesy - SMM Ausaja (Private Collection)

Nargis - Image Courtesy - SMM Ausaja (Private Collection) -

Nargis in Humayun

Nargis in Humayun -

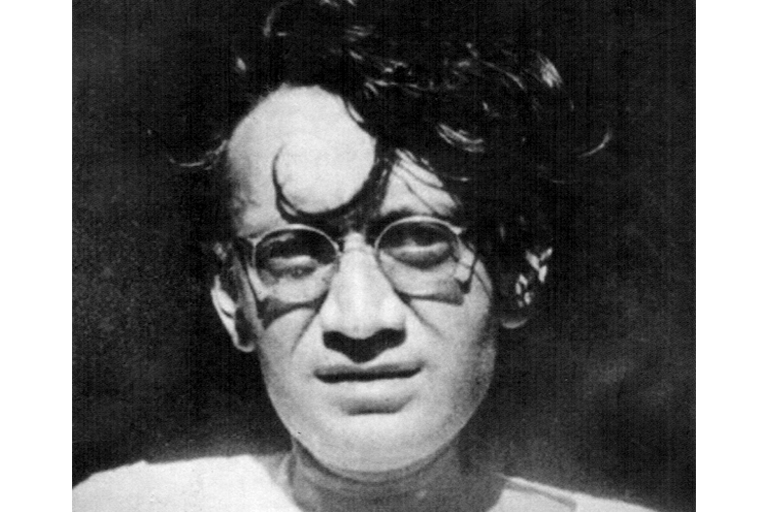

Saadat Hasan Manto

Saadat Hasan Manto

Saadat Hasan Manto was one of the greatest Urdu writers of the last century. He led a rich life, the last years of which, sadly, were given to trials for obscenity, financial troubles and, finally, a liver cirrhosis that was the cause of his death at age 42, in 1955, in Lahore, Pakistan.

In happier years in Bombay, Manto was also a film journalist and a radio and film scriptwriter. As an insider in the Bombay film industry he had a ready window into the lives of the brightest stars of those times.

Here is a translation from the Urdu, of Manto’s account of Nargis— one of Indian cinema’s greatest actresses. Of when her ascent to stardom had just about begun, and of her slow yet studied metamorphosis as an actress.

It was a long time ago. The Nawab of Chattari’s daughter Tasnim—later Mrs. Tasnim Saleem Chattari—had written me a letter: “So what do you think of your brother-in-law, my husband? Since his return from Bombay, he has been talking ceaselessly about you, much to my delight. He was apprehensive of meeting you, my unseen, unmet brother. In fact, he used to tease me about you. Now for the last two days he has been insisting that I should come to Bombay and meet you. He says you are a fascinating person. The way he talks about you, it would seem that you are his brother rather than mine… in any case, he is very happy that I choose people carefully. My own brother got here before Saleem did and lost no time in telling me of his meeting with you. Nargis he never mentioned, but when Saleem arrived and spilled the beans, including your fracas with Nakhshab, only then did everything fall into place. Saleem is apologetic about the second visit to Jaddan Bai’s house and holds his brother Shamshad, whom you have met, responsible for it… You do know, of course, that if Saleem was ever infatuated, it was with Leela Chitnis, which, at least, shows good taste.”

When Saleem dropped in to see me in Bombay, it was our first meeting, and he already was, as Tasnim put it, my brother-in-law, being her husband. I showed him what hospitality I could. Movie people have one ‘present’ they can always give: take their visitors to see a film being shot. So, dutifully, I took him around to Shri Studio where K. Asif was shooting Phool. Saleem and his friends should have been happy with that but it appeared to me that they had other plans, which they obviously had made before arriving in Bombay. So at one point, quite casually, Saleem asked me, “And where is Nargis these days?”

“With her mother,” I replied lightly. My joke fell flat because one of the nawabs asked with the utmost simplicity, “With Jaddan Bai?”

“Yes.”

Saleem spoke next, “Can one meet her… I mean my friends here are quite keen on doing that. Do you know her?”

“I do… but only just,” I answered.

“Why?” one of them asked.

“Because she and I have never worked on a movie together,” I said.

“Then we should really not bother you with this,” Saleem remarked.

However, I did want to visit Nargis. I had decided to do so several times but I had not been able to bring myself to go there. These young men whom I would be taking to see her were the kind who just stare at women with their eyes practically jumping out of their sockets. But they were an innocent lot. All they wanted was to catch a glimpse of Nargis so that when they went back to their lands and estates they would be able to brag to their friends that they had met Nargis, the famous film star. So I told them that we could go and meet her.

Why did I want to meet Nargis? After all, Bombay was full of actresses to whose homes I could go any time I wished. Before I answer that question, let me narrate an interesting story.

I was at Filmistan and my working day was long, starting early and ending at eight in the evening. One day, I returned earlier than usual, in fact, in the afternoon, and as I entered my place, I felt there was something different about it, as if someone had strummed a stringed instrument and then disappeared from view. Two of my wife’s younger sisters were doing their hair but they seemed to be preoccupied. Their lips were moving but I couldn’t hear a word. It was obvious they were trying to hide something. I eased myself into a sofa and the two sisters, after whispering in each other’s ears, said in chorus, “Bhai, salaam.” I answered the greeting, then looked at them intently and asked, “What is the matter?” I thought they were planning to go to the movies but it was not so. They consulted one another, again in whispers, burst out laughing and ran into the next room. I was convinced they had invited a friend of theirs and since I had come in unexpectedly I had upset their plans.

The three sisters were together for some time and I could hear them talking. There was much laughter. After a few minutes, my wife, pretending that she was talking to her sisters but actually wishing me to pay attention, said, “Why are you asking me? Why don’t you talk to him? Saadat, you are unusually early today.” I told her there was no work at the studio. “What do these girls want?” I asked. “They want to say that they are expecting Nargis,” she answered. “So what? Hasn’t she been here before?” I replied, quite sure they were talking about a Parsi girl who lived in the neighbourhood and often visited them. Her mother was married to a Muslim. “This Nargis has never been here before. I am talking of Nargis the actress,” my wife replied. “What is she going to do here?” I asked.

My wife then told me the entire story. There was a telephone in the house and the three sisters loved to be on it whenever they had a minute. When they got tired of talking to their friends, they would dial an actress’s number and carry on a generally nonsensical conversation with her, such as, “Oh! We are great fans of yours. We have arrived from Delhi only today and with great difficulty we have been able to get your phone number… We are dying to meet you… We would have come but we are in purdah and cannot leave the house… You are so lovely, absolutely ravishing and what a wonderfully sweet voice you are gifted with—” although they knew that the voice which was heard on the screen was that of either Amir Bai Karnatiki or Shamshad Begum.

Actresses had unlisted numbers; otherwise their phones would never have stopped ringing. But these three had managed to get almost everyone’s number with the help of my friend the screenwriter Agha Khalish Kashmiri. During one of their phone sessions, they had called Nargis and they liked the way she talked to them. They were the same age and so they became friends and would talk on the phone often, but they were yet to meet. Initially, the sisters did not let on who they were. One would say she was from Africa while the other was from Lucknow who was here to meet her aunt. Or she was from Rawalpindi and had travelled to Bombay just to catch a glimpse of Nargis. My wife would at times pretend to be a woman from Gujarat, at others, a Parsi. Quite a few times, Nargis would ask them in exasperation to tell her who they really were and why they were hiding their real names.

It was obvious that Nargis liked them, although there could have been no shortage of fans phoning her home. These three girls were different and she was dying to know who they really were because she did very much want to meet them. Whenever these three mysterious ones called, she would drop everything and talk to them for hours. One day, Nargis insisted that they should meet. My wife told her where we lived, adding that if there was any difficulty in locating the place she should phone from a hotel in Byculla and they would come and get her. When I came home that day, Nargis had just phoned to say that she was in the area but could not find the house, so they were all getting ready in desperation to fetch her. I had entered at a very awkward time.

The two younger sisters were afraid I would be annoyed, while my wife was just nervous. I wanted to pretend I was annoyed but it did not seem right. It was just an innocent prank. Was my wife behind this madcap scheme or was it her sisters’? It is said in Urdu that one’s sister-in-law owns half the household and here I was, not with one but two. I offered to go out and fetch Nargis. As I walked out of the door, I heard loud clapping from the other room.

In the main Byculla square, I saw Jaddan Bai’s huge limousine— and her. We greeted each other. “Manto, how are you?” Jaddan Bai asked in a rather loud voice. “I am well, but what are you doing here?” I asked. She looked at her daughter who was in the back seat and said, “Nothing, except that Baby has to meet some friends but we can’t find the house.” I smiled. “Let me guide you.” When Nargis heard this, she drew her face close to the window. “Do you know where they live?” “But of course!” I replied. “Who can forget his own house!” Jaddan Bai shifted the paan she was chewing from one side of her mouth to the other and said, “What kind of storytelling is this?” I opened the door and got in next to her. “Bibi, this is no story, but if it is one, then its authors happen to be my wife and her sisters.” Then I told them everything that had happened since I returned home. Nargis listened with great concentration, but her mother was not so amused. “A curse be on the devils… if they had said at the start that they were calling from your home, I would have sent Baby over right away. My, my, for days we were all so curious… By God, you have no idea how excited and worked up Baby has been over these phone calls. Whenever the phone rang, she would run. Every time I would ask her who it was at the other end with whom she had been carrying on such a sweet conversation for hours, and she would reply that she did not know who they were but they sounded very nice. Once or twice, I also picked up the phone and was impressed by their good manners. They seemed to be from a nice family. But the imps would not tell me their names. Today Baby was beside herself with joy because they had invited her to their place and told her where they lived. I said to her, ‘Are you mad? You don’t know who they are.’ But she just would not listen and kept after me, so I had to come myself. Had I known by God that these goblins lived in your house—”

“Then you would not have come personally.” I did not let her complete her sentence.

A smile appeared on her face. “Of course, don’t I know you?” Jaddan Bai was well read and always read my writings. Only recently, one of my pieces, ‘The Graveyard of the Progressives’, had appeared in Saqi, the Urdu literary magazine edited by Shahid Ahmad Dehlvi. God knows why, but she now turned to that. “By God, Manto, what a writer you are! You can really put the knife in, as you did in that one. Baby, do you remember how I kept raving about that article for the rest of the day?”

But Nargis was thinking of her unseen friends. “Let’s go, bibi,” she implored her mother impatiently.

“Let’s go then,” Jaddan Bai said to me.

We were home in minutes. The three sisters saw us from the upstairs balcony. The younger two just could not contain their excitement and were continually whispering in each other’s ears. We walked up the stairs, and while Nargis and the two girls moved into the next room, Jaddan Bai, my wife and I sat in the front room. We amused ourselves by going over the charade the girls had been playing all these months. My wife, now feeling calmer, got down to playing the hostess while Jaddan Bai and I talked about the movie industry and the state it was in. She always carried her paandaan with her because she could not be without her paan, which gave me an opportunity to help myself to a couple as well.

I had not seen Nargis since she was ten or eleven years old. I remembered her holding her mother’s hand on movie opening nights. She was a thin-legged girl with an unattractive long face and two unlit eyes. She seemed to have just woken up or about to go to sleep. But now she was a young woman and her body had filled out in all the right places, though her eyes were the same— small, dreamy, even a bit sickly. I thought she had been given an appropriate name, Nargis, the narcissus.

In Urdu poetry, the narcissus is always said to be ailing and sightless. She was simple and playful like a child and was always blowing her nose as if she had a perennial cold; this was used in the movie Barsaat as an endearing habit. Her wan face indicated that she had acting talent. She was in the habit of talking with her lips slightly joined. Her smile was self-conscious and carefully cultivated. One could see that she would use these mannerisms as raw material to forge her acting style. Acting, come to think of it, is made up of just such things.

Another thing that I noticed about her was her conviction that one day she would become a star, though she appeared to be in no hurry to bring that day closer. She did not want to bid farewell quite yet to the small joys of girlhood and move into the larger, chaotic world of adults with its working life.

But back to that afternoon. The three girls were now busy exchanging their experiences of convent schools and home. They had no interest right now in what happened in movie studios or how love affairs took place. Nargis had forgotten that she was a film star who captivated many hearts when she appeared on the screen. The two girls were equally unconcerned with the fact that Nargis was an actress who was sometimes shown doing rather daring things in the movies.

My wife, who was older than Nargis, had already taken her under her wing as if she were another of her younger sisters. Initially, she was interested in Nargis because she was a film actress who fell in love with different men in her movies, who laughed and cried or danced as required by the script, but not now. She seemed to be more concerned about her eating sour things, drinking ice-cold water or working in too many films as it could affect her health. It was perfectly all right with her that Nargis was an actress.

While the three of us were busy chatting, in walked a relation of mine whom we all called Apa Saadat. Not only was she my namesake, but also a most flamboyant personality, a person who was totally informal, so much so that I did not even feel the need to introduce her to Jaddan Bai. She lowered herself, all two hundred plus pounds of her, on to the sofa and said, “Saffo jaan, I pleaded with your brother not to buy this excuse for a car but he just wouldn’t listen. We had only driven a few yards when the dashed thing came to a stop and there he is now trying to get it going. I told him that I was not going to stand there but was taking myself to your place to wait.”

Jaddan Bai had been talking of some dissolute nawab, a topic Apa Saadat immediately pounced on. She knew all the nawabs and other rulers of the states that dotted the Kathiawar region because her husband belonged to the ruling family of the Mangrol state. Jaddan Bai knew all those princes because of her profession. The conversation at one point turned to a well known courtesan who had the reputation of having bankrupted several princely states. Apa Saadat was in her element. “God protect us from these women. Whosoever falls into their clutches is lost both to this world and the next. You can say goodbye to your money, your health and your good name if you get ensnared by one of these creatures. The biggest curse in the world, if you ask me, is these courtesans and prostitutes… ”

My wife and I were severely embarrassed and did not know how to stop Apa Saadat. Jaddan Bai, on the other hand, was agreeing with all her observations with the utmost sincerity. Once or twice, I tried to interrupt Apa Saadat but she got even more carried away. For a few minutes she heaped every choice abuse on “these women”. Then suddenly she paused, her fair and broad face underwent a tremor or two and the tiny diamond ornament in her nose sparkled even more than it normally did. She slapped herself on the thigh and stammered, looking at Jaddan Bai, “You, you are Jaddan. You are Jaddan Bai, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” Jaddan Bai replied soberly.

Apa Saadat did not stop. “Oh you, I mean, you are a very high-class courtesan, isn’t that so Saffo jaan?” My wife froze. I looked at Jaddan Bai and gave her a smile, which must have been a sheepish one. Jaddan Bai did not flinch, but calmly and in great detail continued her story of this most notorious courtesan. However, the situation could not be recovered. Apa Saadat had finally realized her faux pas and we were too embarrassed to say anything. Then the girls walked in and the tension evaporated. When Nargis was asked to sing, Jaddan Bai told us, “I did not teach her to sing because Mohan Babu was not in favour of it, and the truth is I too was against it. She can sing a bit though.” Then she said to her daughter, “Baby, sing something.”

Like a child, Nargis began to sing. She had no voice at all. It was not sweet nor was the timbre good. Compared to her, my youngest sister-in-law was a thousand times better. However, since Nargis had been asked and asked repeatedly, we had to suffer her for two or three minutes. When she finished, everyone praised her, except Apa Saadat and I. After a few minutes Jaddan Bai said it was time to go. The girls embraced one another and promised to meet again. There was much whispering. Then mother and daughter were gone.

This was my first meeting with Nargis.

I met her several times after this. The telephone was kept busy; the girls would phone her and she would get into her car without her mother and come over. The feeling that she was an actress had almost disappeared. The girls met as if they were related or had known one another for years. Many times, after she had left, the three sisters would say, “There is nothing actress-like about her.”

A new movie starring Nargis was released around this time with quite a few love scenes which showed her whispering coyly to the hero, looking at him longingly, nuzzling up to him, holding his hand and so on. My wife said, “Look at her, the way she is sighing, one would think she really was in love with this fellow.” Her two sisters would say to each other, “Only yesterday she was asking us how to make toffee with raw sugar and here she is… ”

My own view of Nargis’s acting abilities was that she was incapable of portraying emotion. Her inexperienced fingers could not possibly feel the racing pulse of love. Nor could she be aware of the excitement of love, which was different from the excitement of running a race in school. Any perceptive viewer could see from her early movies that her acting was untouched by artifice or deception. The most effective artifice must appear to be natural, but since Nargis was callow and inexperienced, her performances were totally artless. It was only her sincerity and her love for the profession that carried her through her early movies. She was naive about the ways of the world and some of that genuine innocence came through in her performance. Since then, given age and experience, she has become a mature actress. She knows well the difference between love and the games she played at school. She can portray all the nuances of love. She has come of age.

It is good that her journey to acting fame was a slow one. Had she arrived there in one leap, it would have hurt the artistic feelings of perceptive filmgoers. If her off-screen life in her early years had been anything like the roles she was given to play, I for one would have died of shock.

Nargis could have become only an actress, given the fact of her birth. Jaddan Bai was getting on and, though she had two sons, her entire concentration was on Baby Nargis, a plain-looking girl who could not sing. However, Jaddan Bai knew that a sweet voice could be borrowed, and if one had the talent even the disadvantage of ordinary looks could be surmounted. That was why she had devoted herself entirely to Nargis’s development and ensured that whatever talent her daughter had was fully brought out and made central to her personality. Nargis was destined to become an actress and she did become one. The secret of her success, in my opinion, was her sincerity, a quality she always retained. In Jaddan Bai’s family there was Mohan Babu, Baby Nargis and her two brothers. All of them were the responsibility of Jaddan Bai. Mohan Babu came from a rich family and had been so fascinated with the musical web Jaddan Bai’s mellifluous voice had woven around him that he had allowed her to become his entire life. He was handsome and he had money. He was also an educated man and enjoyed good health. All these assets he had laid at her feet like offerings in a temple. Jaddan Bai enjoyed great fame at the time. Rajas and nawabs would shower her with gold and silver when she sang. However, after this rain of gold and silver was over, she would put her arms around Mohan because he was all she really cared about. He stayed by her side until the end and she loved him deeply. He was also the father of her children. She had no illusions about rajas and nawabs; she knew that their money smelt of the blood of the poor. She also knew that when it came to women, they were capricious.

Nargis was always conscious that my sisters-in-law, whom she came to meet, and spent hours with, were different from her. She was always reluctant to invite them to her home, afraid that they might say it was not possible for them to accept her invitation. One day when I was not around, she told her friends, “Now you must come to my home some time.” The sisters looked at one another, not sure what to say. Since my wife was aware of my views, she accepted Nargis’s invitation, but she did not tell me. All three went.

Nargis had sent them her car and when it arrived at Marine Drive, Bombay’s most luxurious residential area, they realized that Nargis had made special arrangements for them. Mohan Babu and his two grown-up sons had been asked not to stay around because Nargis was expecting her friends. The male servants were not allowed into the room where the women were. Jaddan Bai came in for a few minutes, exchanged greetings and left. She did not want to inhibit them in any way. All three sisters kept saying later how excited Nargis was by their presence in her home. Elaborate arrangements had been made and special milk shakes had been ordered from the nearby Parisian Dairy. Nargis had gone herself to get the drinks because she did not trust a servant to get the right thing. In her excitement and enthusiasm, she broke a glass, which was part of a new set. When her guests expressed regret, she said, “It’s nothing. Bibi will be annoyed but daddy will quieten her down and the matter will be forgotten.”

After the milk shakes, Nargis showed them her albums of photographs, which had stills from many of her movies. There was a world of difference between the Nargis who was showing them the pictures and the Nargis who was the subject of those pictures. Off and on, the three sisters would look at her to compare her with the movie photographs. “Nargis, how do you become Nargis?” one of them asked. Nargis merely smiled. My wife told me that at home Nargis was simple, homely and childlike, not the bouncing, flirtatious girl whom people saw on the screen. I always felt a sadness floating in her eyes like an unclaimed body in the still waters of a pond whose surface is occasionally disturbed by the breeze.

It was clear to me that Nargis would not have to wait long for the fame which was her destiny. Fate had already taken a decision and handed her the papers, signed and sealed. Why then did she look sad? Did she perhaps feel in an unconscious way that this make-believe game of love she played on the screen would one day lead her to a desert where she would see nothing but mirage followed by mirage, where her throat would be parched with thirst and the clouds would have no rain to release? The sky would offer no solace, and the earth would suck in all moisture deep into its recesses because it would not believe she was thirsty. In the end, she herself would come to believe that her thirst was an illusion.

Many years have passed and when I see her on the screen, I find that her sadness has turned into melancholy. In the beginning, one felt that she was searching for something but now even that urge has been overtaken by despondency and exhaustion. Why? This is a question only Nargis could answer.

But back to the three sisters at Nargis’s house. Since they had gone there on their own, they did not stay long. The two younger ones were afraid I would find out and be annoyed, so they took Nargis’s leave and came home. I noticed that whenever they talked about Nargis, it would come to the question of marriage. The younger ones were dying to know when or whom she would marry, while my wife, who had been married for five years, would speculate about what kind of mother Nargis would make.

My wife did not tell me at first about their visit, but when she did I pretended to be displeased. She was immediately on the defensive and agreed that it was a mistake. She wanted me to keep it to myself because, according to the moral and social milieu in which the three had been brought up, visiting the home of an actress was improper. As far as I know, they had not told even their mother that they had gone to see Nargis, although the old lady was by no means narrow-minded. To this day, I do not understand why they thought they had done something wrong. What was wrong with going to see Nargis at her home? Why was acting considered a bad profession? Did we not have people in our own family who had spent their entire lives telling lies and practising hypocrisy? Nargis was a professional actress. What she did, she did in the open. It was not she but others who practised deception.

Since I began this account with Tasnim Saleem Chattari’s letter, let me return to it because that is what set the whole thing off. Since I was keen to meet Nargis at her own place, I went along with Saleem and his friends despite being busy. The correct thing would have been to phone Jaddan Bai to see if Nargis was free or not, but since in my daily life I was no great believer in such formalities, I just appeared at her door. Jaddan Bai was sitting on her veranda, slicing betel nut. As soon as she saw me, she said in a loud voice, “Oh! Manto, come in, come in.” Then she shouted for Nargis, “Baby, your sahelis are here,” thinking that I had brought my two sisters-in-law. When I told her that I was accompanied not by sahelis but sahelas, and also who they were, her tone changed. “Call them in,” she said. When Nargis came running out, she said to her, “Baby, you go in, Manto sahib has his friends with him.” She received Saleem and his companions as if they were buyers who had come to inspect the house. The informality with which she always spoke to me had disappeared. Instead of “Sit down”, it was “Do please make yourselves comfortable”, and “Want a drink?” had become “And what would you prefer for a drink?” I felt like a fool.

When I told her the purpose of our visit, her rather studied and stylized reply took me aback. “Oh! They want to meet Baby? The poor thing has been down with a bad cold for days. Her heavy work schedule has taken the last ounce of energy out of her. I tell her every day, ‘Daughter, just rest for a day.’ But she does not listen, so devoted is she to her work. Even director Mehboob has told her the same thing, offering to suspend the shooting for a day, but it has no effect on her. Today, I put my foot down because her cold was bad. Poor thing!”

Naturally, my young friends were gravely disappointed when they heard that. They had caught a glimpse of her from the taxi when she had briefly run on to the veranda, but they were dying to see her from close quarters and were disappointed that she was ill. Jaddan Bai, meanwhile, had begun to talk of other things and I could see that my young friends were bored. Since I knew there was nothing the matter with Nargis, I said to Jaddan Bai, “I know it is going to be hard on Baby but they have come from so far; maybe she could come in for a minute.”

After being summoned three or four times, Nargis finally appeared. All of them stood up and greeted her in a very courtly manner. I did not rise. Nargis had made the entry of an actress. Her conversation too was that of an actress, as if she were delivering her given lines. It was quite silly. “It is such a great pleasure to meet you”. “Yes, we only arrived in Bombay today”. “Yes, we will be returning the day after”. “You are now the top star of India”. “We have always seen the opening show of every one of your movies”. “The picture you have given us will go into our album”. Mohan Babu also joined us at one point but he did not say a word, just kept looking at us with his big eyes before going into some reverie of his own.

Jaddan Bai spoke most of the time, making it clear to her visitors that she was personally acquainted with every Indian raja and nawab. Nargis’s entire conversation was pure artifice. The way she sat, the way she moved, the way she raised her eyes, was like an offering on a platter. Obviously, she expected them to respond in the same self-conscious, artificial manner. It was a boring and somewhat tense meeting. The young men felt inhibited in my company, as I did in theirs. It was interesting to see a different Nargis from the one to whom I was accustomed. Saleem and his friends went to see her again the next day, but without telling me. Perhaps this meeting was different. As for my argument with the poet Nakhshab to which Tasnim Saleem had referred in her letter, I do not have the least recollection of it. It is possible he was there when we arrived because Jaddan Bai was fond of poetry and liked to entertain poets and have them recite. It is possible I may have had a tiff with Nakhshab.

I saw another aspect of Nargis’s personality once when I was with Ashok. Jaddan Bai was planning to launch a production of her own and wanted Ashok to play the lead, but since Ashok, as usual, did not want to go by himself, he had asked me to come along. During our conversation, we discussed many things but discreetly, things such as business, money, flattery and friendship. At times, Jaddan Bai would talk as a senior, at others as the movie producer and at times as Nargis’s mother who wanted the right price paid for her daughter’s work. Mohan Babu would nod his agreement now and then.

They were talking big money, money which was going to be spent, money which had been spent. However, each paisa was carefully discussed and accounted for. Nargis was pretty businesslike. She seemed to suggest, “Look Ashok, I agree that you are a polished actor and famous but I am not to be undermined. You will have to concede that I can be your equal in acting.” This was the point she wanted to hammer home. Off and on, the woman in her would come to life, as if she were telling Ashok, “I know there are thousands of girls who are in love with you, but I too have thousands of admirers and if you don’t believe that, ask anyone… maybe you too will become my admirer one of these days.”

Periodically, Jaddan Bai would play the conciliator. “Ashok, the world is crazy about you and Baby, so I want the two of you to appear together. It will be a sensation and we will all be happy.” Sometimes, she would address me. “Manto, Ashok has become such a great star and he is such a nice man, so quiet, so shy. God grant him a long life! For this movie, I have had a role specially written for him. When I tell you all about it, you will be thrilled.”

I did not know what role or character she had got specially written for Ashok, but anyway I was happy for her. It did occur to me though that Jaddan Bai herself was playing a most fascinating role, and the one she had chosen for Nargis was even more fascinating. Had this been a scene being shot with Ashok, she could not have spoken her lines with more conviction. At one point, Suraiya’s name came up and she pulled a long face and started saying nasty things about her family and pulling her down as if she were doing it out of a sense of duty. She said Suraiya’s voice was bad, she could not hold a note, she had had no musical training, her teeth were bad and so on. I am sure had someone gone to Suraiya’s home, he would have witnessed the same kind of surgery being performed on Nargis and Jaddan Bai. The woman whom Suraiya called her grandmother, but who was actually her mother, would have taken a drag at her hookah and told even nastier stories about Jaddan Bai and Nargis. I know that whenever Nargis’s name came up, Suraiya’s mother would look disgusted and compare her face to a rotting papaya.

Mohan Babu’s big, handsome eyes have been eternally closed for many years and Jaddan Bai has been lying under tons of earth for a long time, her heart full of unrequited desires. As for her Baby Nargis, she stands at the top of that make believe ladder we know as the movies, though it is hard to say if she is looking up, or if she is looking down at the first rung on which she put her tiny child’s foot many years ago. Is she seeking a patch of dark under those brilliant arc lights that illuminate her life now, or is she searching for a tiny ray of light in that darkness? This interplay of light and dark constitutes life, although in the world of movies there are times when the dividing line between the two ceases to exist.

Excerpted with permission from Penguin Books India from Stars from Another Sky by Saadat Hasan Manto (Rs. 250). You can buy the book here.

Also listen to:

The Narcissus of Undying Bloom

ArticleMay 2013