-

Illustration by Amrita Bagchi for TBIP

Illustration by Amrita Bagchi for TBIP -

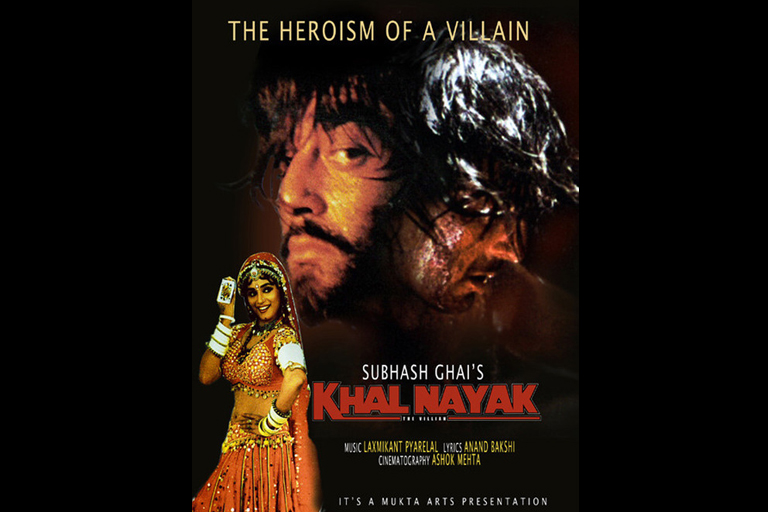

Poster of Khal Nayak

Poster of Khal Nayak -

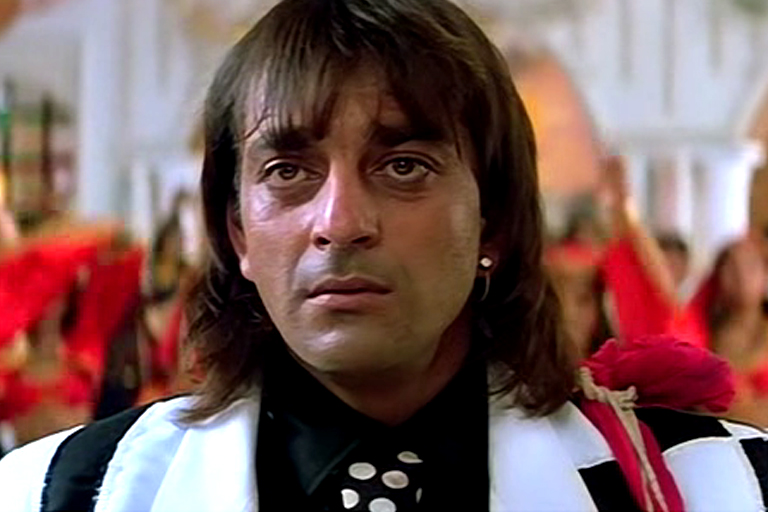

A screenshot from Khal Nayak

A screenshot from Khal Nayak -

A screenshot from Khal Nayak

A screenshot from Khal Nayak -

A screenshot from Khal Nayak

A screenshot from Khal Nayak -

The Maruti Omni

The Maruti Omni -

The Katta or country-made pistol

The Katta or country-made pistol

Palash Krishna Mehrotra on Khal Nayak, Sanjay Dutt and the Bad Boys of Allahabad

Received wisdom says that Hindi cinema is fantasy-laden and escapist. Growing up in Allahabad in the 1980s and nineties, my experience of it was vastly different. Bombay films were, for the young men in that town, so real that the cows and motorcycles and colonial bungalows outside the theatre could have existed in a world of make-believe. What happened in the darkness of a single screen hall in the old part of town was what the world was really like— the world as it was.

Young Allahabadis copied the hairstyles of their favourite film stars. Anil Kapoor, Sanjay Dutt and local boy, Amitabh Bachchan, were the most popular ones at barbershops. Rahul Roy’s foppish hairdo was considered too wimpy for macho eastern Uttar Pradesh and never took off, even though Aashiqui was a super hit. They mugged up dialogues from these films, played film music from loudspeakers mounted on electricity poles, and fantasized about Bollywood heroines in wet saris. But then, this could have happened anywhere in north India. There was something else that made this connection with Hindi cinema unique and vital for Allahabadis in their teens and early twenties. It was the violence. There was plenty of it in films of that period.

Allahabad (and eastern UP as a whole) was known for gangsters and low-grade violence. Getting access to crude bombs and kattas (country-made pistols) was easy and people made use of this. In a town with few opportunities in pre-liberalization India, there was really nothing to do. Everyone had a big provincial ego (matched by a paranoid provincial imagination). The thing to do was to pick fights, often over imagined insults. “He was staring at me.” “I saw him talking to a girl I fancy.” “Who does he think he is?”

Being a gangster was glamorous. They came in different shapes and sizes. To do anything in the town you needed the ‘backing’ of a goonda. If you were a crow, you needed a friendly buffalo on whose back you could hitch a ride. Some buffalos were modest, while others claimed the backing of bigger hoodlums— those who were part of the university students’ union, or the youth wing of a political party. Your stature was decided by the number of followers (muscle power), access to bombs and kattas (firepower) and how much ‘area’ you controlled. As one of the small-time gangsters explained to me, his area ran from the cycle repair shop in Rajapur to the cycle repair shop near Boys’ High School. A bigger fish would, say, control all of Attarsuiya, a large neighbourhood in the Muslim part of town.

The police were held in contempt. They were there to be made fun of. There were stories of skirmishes between the two sides where the gangster always came out on top. In some, the policeman would fall at the gangster’s feet and beg for mercy. Much of this was apocryphal, mere bravado, but it was certainly the way people spoke about cops. The allure, for us, was always to be the goonda who exercised feudal control over an area, in complete contempt of the organs of the state. The cop’s only hope lay in being a gangster’s stooge.

It was an absurd, desolate and violent landscape. It was not all talk. People actually did get their arms blown off in crude bomb attacks. And in this landscape, violent Hindi films about angry young men who lived on their own terms, and cocked a snook at the police, had an immediate connect. The celluloid world put together in faraway Bombay was palpably real, more real than the hot winds that blew through the streets of the town every May and June.

* * *

Subhash Ghai’s Khal Nayak released in the summer of 1993. I was 16. The film went on to become one of the biggest blockbusters of Hindi cinema. It was also the year that Sanjay Dutt was in and out of jail in connection with the Bombay Blasts case. In the days leading up to its release, anticipation had reached fever pitch in Allahabad. After all, the movie was about a real life bad boy who played a reel life bad boy. The bad boys of Allahabad couldn’t wait to enter the theatre; the film promised to tell their story.

By 1993, Palace and Plaza, the two theatres in downtown Civil Lines had gone to seed. They’d been reduced to showing re-runs of Bollywood films; the projection was shaky and the audio muffled. As a child, I’d gone to Palace with my parents and watched The Godfather, Kramer vs. Kramer, 36 Chowringhee Lane, The Jungle Book and Bugs Bunny. Now, if one wanted to see a new Hindi film, one had to make the trek to Chowk, the ‘black’ town.

One afternoon, Aditya, a friend from school, turned up at my place with two tickets for Khal Nayak. He’d bunked school, stood in a long queue, been lathi-charged by the police, and finally emerged with two tickets bought in black. There was little time to lose. I decided to bunk tuition, hopped on his Luna, and off we went to Chowk, zigzagging through the usual traffic of cycles, cycle rickshaws, Bajaj scooters, TVS Suzuki motorbikes and Maruti 800s.

There was a huge crowd of men outside the theatre, some holding hands, some walking around with their arms slung around each other, everyone greeting everyone with a cordial “Kas be bhosdi ke!” There was a posse of policemen with lathis standing on the sidelines and watching this gathering of aspiring gangsters. It looked like a riot would break out any moment.

We entered the lower stalls in a frenzy of pushing and shoving. It was like boarding a Borivali slow train at Dadar, Mumbai, at 8 pm. You did nothing. You just went with the flow of the crush. The hall was packed to beyond its capacity. Men walked in and out at will, their narrow chests puffed out. Some had seen the film earlier and only wanted to watch a particular song or catch a dialogue again. Sunlight streamed in through the open doors. Mongrels squatted in the aisles. And almost everyone was smoking a Capstan cigarette.

Sanjay Dutt’s entry was greeted with hooting, whistling and clapping. When Choli Ke Peechey (banned on Vividh Bharti) came on, they showered the screen with coins. There was a lot of noise in general and the conversations didn’t cease right through the film. People passed loud comments, scratched their balls and told the cop, Ram, (played by Jackie Shroff) to get out of their faces. The loudest cheers were reserved for the scene where Ballu (Sanjay Dutt), a gangster, escapes from jail.

Sanjay Dutt’s jail stints that year had been all over the papers. For the audience, what was happening on screen was like reality television. It might be edited and doctored but it was still very real. Sanju hadn’t just emerged from jail in the movie; he had done so in actuality. He had fooled the police and walked to freedom. He was once again in a world which he could control. The invincible Ballu could go back to doing what he did best: impose order on chaos or vice versa, depending on which side of the divide you were on. And do so on his terms. This called for celebration. Crackers went off in the theatre; loud bombs that filled the hall with thick smoke and momentarily obscured the screen. We didn’t know if the bombs were real or not. There was a stampede. Strangely, people giggled as they fell over each other. My friend and I clambered onto our seats and continued to watch the film. After all, we had bought the tickets in black, at a price that was way above our weekly pocket money. After a while, the celebrations subsided, the smoke cleared and everyone went back to watching the show, hooting, and puffing on their Capstans. Their man Sanju (not Ballu) was safe for the moment.

* * *

The next morning, back in school, we waited for assembly to begin. The only talking point was Khal Nayak. Those who had seen it wore a distinctly superior air. We were all terribly distracted. It took us two false starts to get the Lord’s Prayer going in unison. We’d just about reached “Give us this day our daily bread”, when someone at the far corner of the field caught our eye. As the looming figure came closer we recognized him to be our classmate, Rakesh Pandey. This was sensational.

Rakesh Pandey had seen Khal Nayak, first day, first show. We respected him for pulling that off, but that wasn’t the only reason we held him in high esteem. His father had recently bought a new Maruti Omni. After watching the movie, Pandey had decided to take the van for a spin, and in a moment of gangsta inspiration, had impulsively kidnapped a boy in his neighbourhood. Over the years, the Omni would earn itself a reputation for being the favoured vehicle of kidnappers in UP and Bihar, its sliding doors making it easy to pull the unsuspecting victim in. Pandey was one of the first in Allahabad to notice and tap this potential in the car. Unfortunately, the boy he’d kidnapped belonged to a powerful family, and his father promptly got Pandey arrested and thrown in jail. He’d managed to get out, just like Ballu, just like Sanju, and now he was nonchalantly making his way to the assembly, a full ten minutes late. He walked with deliberate slowness. He wasn’t carrying a bag, just a register to write in. He had emerged from a real prison while we were still imprisoned in a fake one.

At that moment several images merged in our minds. These were separate to begin with, but over the previous week had coalesced into one: reel had become real and real had become reel. Sanju Baba in and out of prison, Ballu, the khal nayak, in and out of prison, and now Rakesh Pandey. When we saw him in the distance, in our mind’s eye we saw that long shot in the movie when we see a clean-shaven Ballu walking, his silhouette framed against the sky, a free man again, a gangster in complete charge of his destiny. Pandey too saw himself in the same way.

Trackbacks

WHEN SANJAY MET PANDEY

ArticleMay 2013

By Palash Krishna Mehrotra

By Palash Krishna Mehrotra

Palash Krishna Mehrotra was born in Bombay in 1975, and educated at St. Stephen's College, Delhi, the Delhi School of Economics, and Balliol College, Oxford. His collection of stories, Eunuch Park, was shortlisted for The Hindu Fiction Prize and the Shakti Bhatt First Book Prize. He the editor of an anthology, Recess: The Penguin Book of Schooldays, and, most recently, the author of a book of nonfiction, The Butterfly Generation. He writes a fortnightly column for Mail Today Sunday, and is a Contributing Editor at Rolling Stone. He lives in between New Delhi and Dehradun. Photo Credit : Parikhit Pal

lunette carrera…

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an incredibly long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyway, just wanted to say fantastic blog!…