-

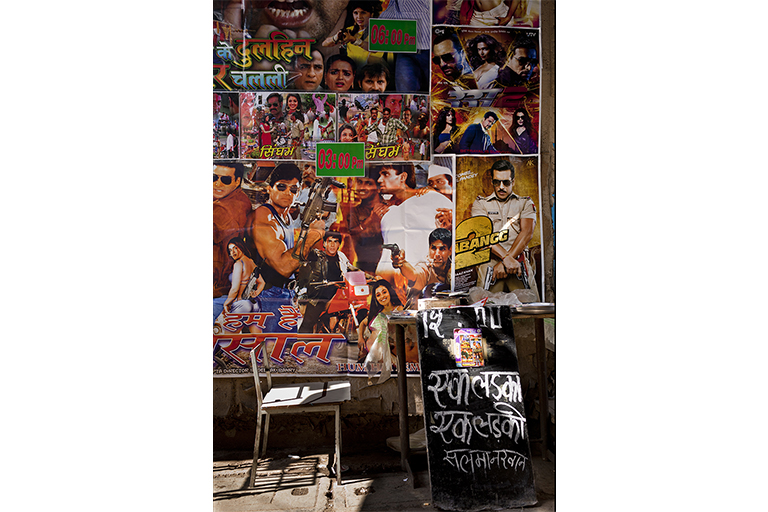

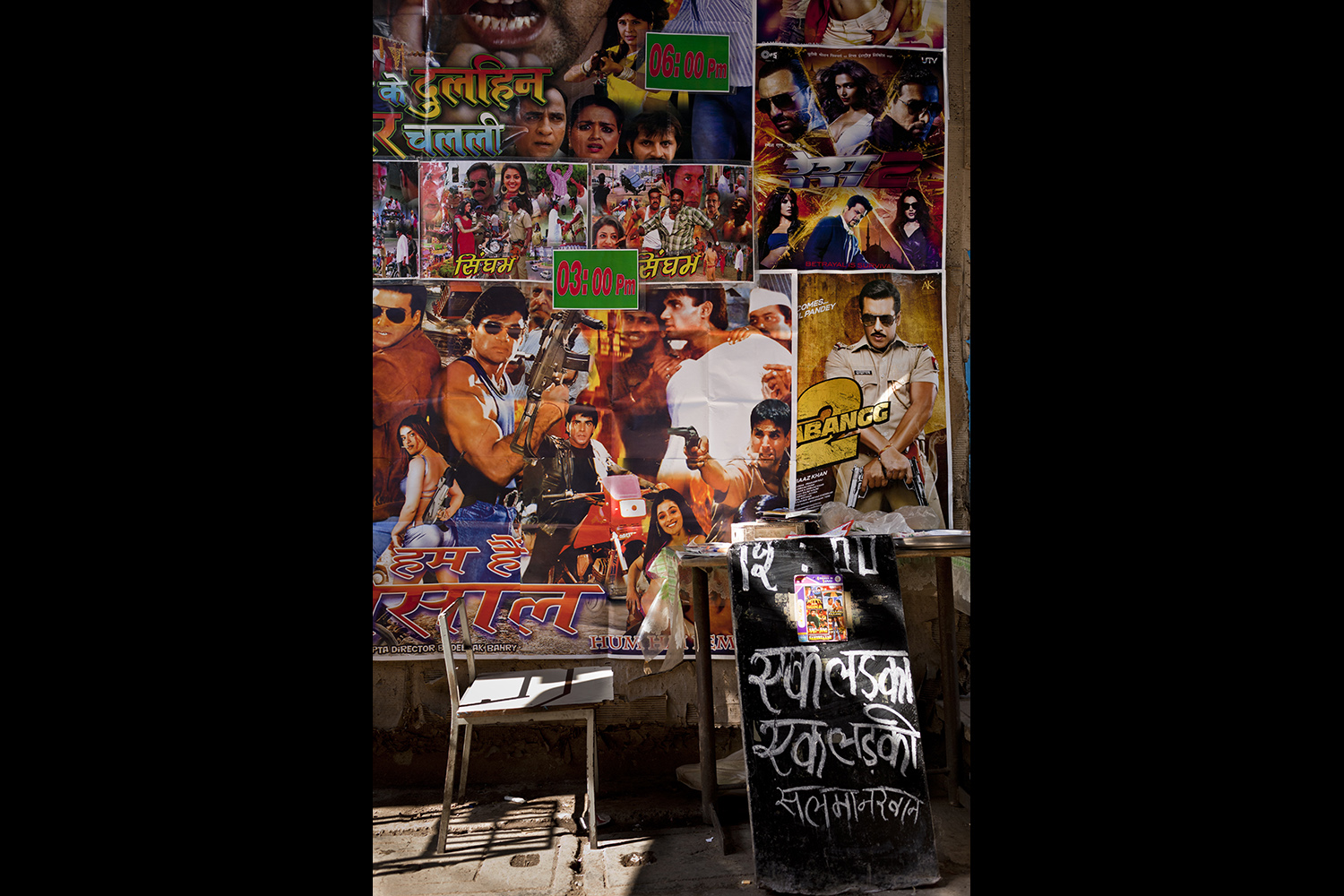

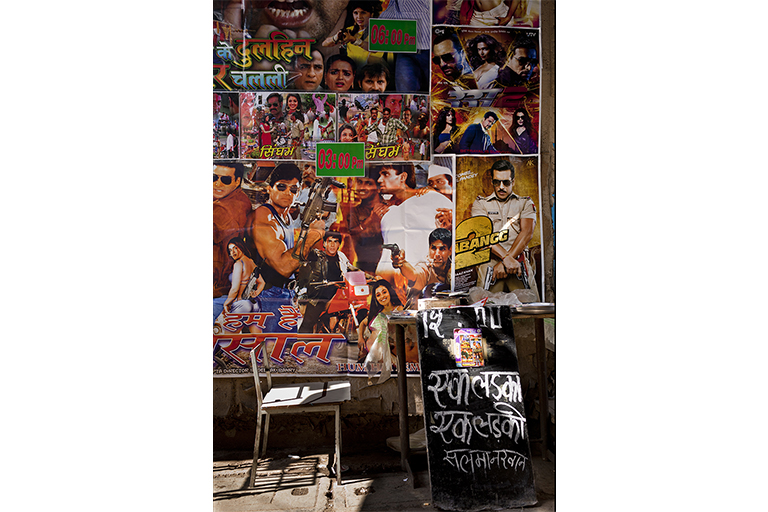

The wall outside Mahesh Video Centre, plastered with posters of the day's films | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture

The wall outside Mahesh Video Centre, plastered with posters of the day's films | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture -

Tickets sold at Kishore Stores | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture

Tickets sold at Kishore Stores | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture -

The ticket counter for Mahesh Video Centre. Behind the curtain is the room for the Rajshree Lottery | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture

The ticket counter for Mahesh Video Centre. Behind the curtain is the room for the Rajshree Lottery | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture -

The lane on which Mahesh Video Centre and Kishore Stores stand | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture

The lane on which Mahesh Video Centre and Kishore Stores stand | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture -

Patrons watching a cricket match at Mahesh Video Centre | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture

Patrons watching a cricket match at Mahesh Video Centre | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture -

A Tamil film playing at Kishore Stores' theatre | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture

A Tamil film playing at Kishore Stores' theatre | Sheetal Mallar for The Big Indian Picture

The story of ‘Chhota Dharavi’ and its unique cinematic culture.

In the early afternoon in Orlem, Malad, a few construction workers are walking home for lunch. Children in white and blue uniforms are on their way back from school. Amidst the regular sounds of traffic one can hear snatches of conversation in Tamil. Along this road are small eateries with giant sizzling griddles set up at their entrances; churning out dosas. Up ahead is a tiny building with a banner announcing it to be Velankanni Church, a replica of the famous basilica of Our Lady of Good Health located in a small town called Vailankanni in the Nagapattinam district of Tamil Nadu. Along with Hindi and English, the signboards on shops have the squiggly lines of Tamil letters. This street could be anywhere in Tamil Nadu, except it is not. Orlem, Malad, is a small lower middle-class neighbourhood in the Western suburbs of Mumbai. On Google Maps, Orlem is yet another mass of tiny grey squares that the arterial Link Road, linking, as its name suggests, some of Mumbai’s largest suburbs, melts into at some point. Walking along the path that turns off Link Road, the grey clusters reveal themselves to be a densely packed colony with many narrow lanes lined with small shops, and one-room houses stacked one on top of the other.

On one such lane stands Mahesh Video Centre, run by 37 year old Mahesh Chelladurai Nader. Approximately 40 years ago, it was set up by his father Jeyaraj Chellaya Nader. Although his family hails from Tirunelveli in Tamil Nadu, Mahesh was born and brought up in Orlem. He saw the colony grow from a largely desolate area to the densely packed community that it is today. A new film poster is going up on the outside wall of his theatre. People stop by to see which film is going to play in the evening. The man putting up the poster pats Akshay Kumar’s face into place. Khiladi 786 at 6:30 pm. At his theatre, Mahesh usually screens Hindi and Bhojpuri films to cater to his usual audience: migrant labourers from Uttar Pradesh—or the bhaiyya log as they are called in these parts—who live and work in the area. The theatre is a large room with a six by eight feet projection screen at one end. At a time, an audience of up to 40 people can seat themselves on the two rows of wooden benches in this theater. The wall outside the theatre is plastered with posters of the films playing at various times. “This is the oldest video parlour in the area,” Mahesh claims. Every once in a while, he also screens cricket matches. On these rare occasions, the bhaiyya log and the anna log (the Tamilians) sit in together. A match is on today. India is playing Pakistan in the third match of the One Day International series. Arun Kumar, 22, a young call centre employee and frequent patron of the theatre, stands outside, bored. “They won’t play a film till the match is over,” he says.

Kumar walks down to Kishore Stores to buy a cigarette. Standing a mere 20 metres away, Kishore Stores is run by Ravi Raman and his older brother V. S. Ponpandi. The hole in the wall selling tobacco and candy leads into a video parlour of its own. Ponpandi, 55, came from Madurai to Bombay when he was 16. He first worked in a steel company near Borivali station and lived in Kajupada in Borivali East for a while before coming to Orlem. “We heard that our people are here, so we came here.” Ponpandi started Kishore Stores to cater to the settlement’s need for Tamil entertainment. “We thought there is no cable here and our people are here, so we could show them Tamil films.”

In a tacit agreement with Mahesh Video Centre, Kishore Stores shows only Tamil films, switching occasionally to a Telugu or Malayalam film when they are running low. But, he says, he never screens new films running in the multiplexes or big theatres. Instead, he waits for the ‘master print’ to come out. In the parlance of video parlours, a ‘master print’ is a legal, non-pirated DVD of a film.

Their theatre is a room behind the store. Ravi, 35, manages the store out front and monitors the film playing on the five by six feet screen through a hole in the back of his store. While he claims his theatre can accommodate 50 people, it is a smaller space with around 20 plastic chairs. Appu, 25, a frequent viewer at Kishore Stores, works at a construction site nearby and comes to catch a film whenever he can. When asked if he frequents Mahesh’s video parlour as well, he says: “They (Bollywood) copy everything from us, then why watch them?”

Ponpandi of Kishore Stores also helped Padma Theatre set up its business. Padma Theatre is on a parallel street further down the road, a little removed from these two video parlours. The lane leading to it is very narrow, barely allowing for two people to walk side by side. The video parlour is named after the owner Chinna Durai’s wife. The owner’s family rented their business out to a man named Thirumani, 32, a short, stocky man with paan stained lips and a red tilak on his forehead, and went back to their village in Tamil Nadu. Thirumani has been running the theatre for about a year now. At Padma, films are screened in two rooms, each seating 20 to 25 people. It shows both Tamil and Telugu films. With a business-like demeanor, Thirumani insists on shaking hands at the beginning and end of every meeting but when it comes to talking about the running of his business he is wary. “I show only master prints, never the films running in theatres,” he says. “We have to be careful because if they (the multiplexes) hear about it, there will be raids.” He is not as concerned about the legality of his business as he is about riling up the big guys who run multiplexes.

***

Ravi may have an understanding with Mahesh Video Centre about the kind of films each one runs but he quashes claims that it is older than Kishore Stores, insisting theirs is the oldest video parlour in the area. He remembers how in the early years the area was deserted, like a “jungle”. “From the main road, there was one narrow path that came till here and only one person could walk on it at a time. In the beginning there was nothing here. We would go to the Somwar (Monday) Market near Chincholi Bunder.” Or they would frequent the Tamil stores in Dharavi—Mumbai’s vast and famous slumland that is known for its Tamil ghetto—for masalas, magazines, film DVDs and food. “There was only vada pav in this area. Now there are three to four South (Indian) hotels.” Shops in the area provide for everything Tamil. Kishore Stores alone sells four to five different Tamil magazines. Pointing to the string of plastic packets of a popular South Indian fried snack called murukku in his store, he says, “Now we get everything here.”

According to Mahesh, the first group of Tamil migrants came to Orlem around 30 years ago when they were rehabilitated from Sion-Koliwada, a locality that lies on the fringes of Dharavi. They were resettled, says Mahesh, because of “road cutting”, or the construction of a road that would require the partial or complete demolition of their houses, which stood in its way. Once the migrants settled here, the community grew rapidly. While the address on the signboards of the stores read Jay Janta Nagar, Orlem, Appu says the area is also known as ‘Chhota Dharavi’ or ‘Small Dharavi’. “Ask anyone in the area,” he says. “People know this is Chhota Dharavi.” A.M. Kennedy, 42, another Tamil migrant who owns a DVD store on this street, which sells the latest Tamil and Hindi film releases, vehemently disagrees. “That’s not at all right,” he says. “This is Orlem.” Kennedy himself does not live in this cluster but in “an apartment building on the main road”. At least, that’s how he tries to distinguish himself from the inhabitants of the area. Perhaps, for similar reasons, for the fear of being equated with those living or working in slums—at the bottom of the city’s food chain—or for the fear of being viewed as someone who still lives in a ‘ghetto’, Kennedy is adamant about “Orlem” not being called Chhota Dharavi. Yet, his objections notwithstanding, the title seems to have stuck and the analogy is not completely off the mark either. Urban researchers Matias Echanove and Rahul Srivastava, who have worked in Dharavi for several years say that the fishing village of Koliwada is one of the oldest parts of Dharavi, and Tamil migrants were one of the first to settle there. Some of these settlers, twice-migrants now, eventually moved to Orlem.

All three video parlour owners insist that their viewership also includes families of the neighbourhood, but their assertions do not check out. Women and children are hardly to be seen in these rooms crowded with men. Since the advent of TV and the internet in the neighbourhood the numbers of those frequenting the video parlours have been considerably reduced. Families in the neighbourhood say they now go to Cinemax, a multiplex that is part of a chain, not far off, to watch movies. The video parlours’ audience comprises mostly labourers like Appu from the nearby construction sites who come to catch a film during their breaks from work, or young men of the neighbourhood like Arun Kumar, who works night shifts at his call centre and has free time during the day. Laxmi, 39, a housewife who lives in a one-room house close by, says that the parlours are “for men” and not family places. Her family watches films on TV or goes out to the multiplexes. A huge Rajinikanth fan, Ravi, despite owning a video parlour, himself goes to PVR Goregaon, another multiplex, to watch the star’s latest films. Muthukumaran, 26, who works the ticket counter at Padma Theatre, watches the films of his favourite actor Vijay at whichever multiplex it is being screened at in the city, sometimes travelling for hours to as far as South Mumbai, the area known as ‘town’, to catch them. The larger-than-life world of Tamil cinema may not bring back memories of their life in Tamil Nadu, but it forges a bond between disparate lives. For most of these migrants, the state is now more an idea of home than home itself. It is this sense of place and identity that they seek to recreate. The video parlours have been an integral part of this recreation of a community— far away from its place of origin.

Despite the many years behind them, the struggle for survival now haunts the parlours. Thirumani admits that he can barely make ends meet and is just about managing to pay rent. Ravi insists that dividing the language market between them has meant that his business is not affected by Mahesh’s. But the crowds of people inside and outside Mahesh’s theatre are significantly higher than those at Kishore Stores and Padma Theatre. This is partly due to the vada pav seller and the tea seller who have set up station there, who serve customers on the street and in the theatres. But that is not the only reason. In a bid to survive Mahesh has adapted, creating other avenues to expand and stabilize his business. He has rented out the room next to his ticket counter to let someone run the Rajshree Lottery (an internet-based lottery scheme that is licensed out by the Arunachal Pradesh state government) there. Also, his screenings of cricket matches draw customers who would not usually go to the video parlour to watch films. A few months ago, Mahesh Video Centre switched to paying for non-pirated film prints provided by United Mediaworks (UMW) which seeks to provide small video theatres with legal prints of new releases. When asked why he switched, Mahesh says there was no particular reason. He just wanted to try it. But he is happy about the decision. The difference, he says, is in the quality of the films and also the quicker access he gets to newer films. While earlier he would have to wait a few months for the DVDs of a film, now UMW lets him get his hands on a new film within two weeks of its release. Despite the hike in ticket price, from Rs 10 a ticket to Rs 20, patrons continue to flock to his theatre. The switch has also eased his worries about raids, although he claims he was “never worried in the first place”. The migrants of Orlem are used to living on the edge.

Moving Images from the Ghetto

ArticleJuly 2013

By Meryl Mary Sebastian

By Meryl Mary Sebastian

Meryl Mary Sebastian is Junior Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture

By Sheetal Mallar

By Sheetal Mallar

Sheetal Mallar has been one of the country's leading models, having worked with design-houses like Armani, Fendi, Rohit Bal, Sabyasachi and Manish Arora, and brands like L'oreal, Maybelline, Damas and Grasim. As a photographer she has been working on a project called 'Alone Together' which is about urban youth in big cities. She is also interested in documenting urban subcultures. Her photographs have been published in publications like Motherland magazine, Vogue, GQ, and Conde Nast Traveller India.