-

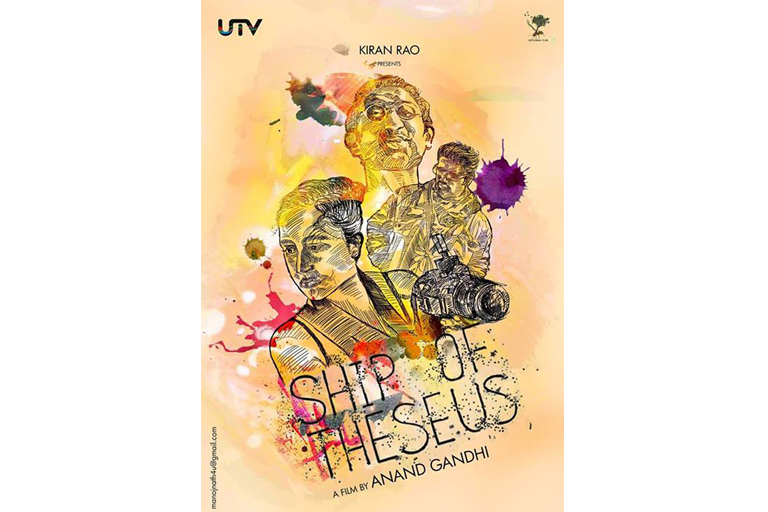

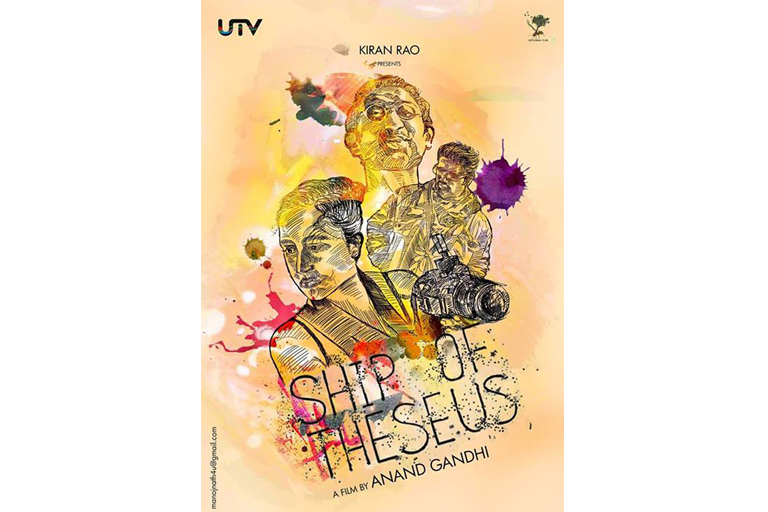

Poster of Ship of Theseus

Poster of Ship of Theseus -

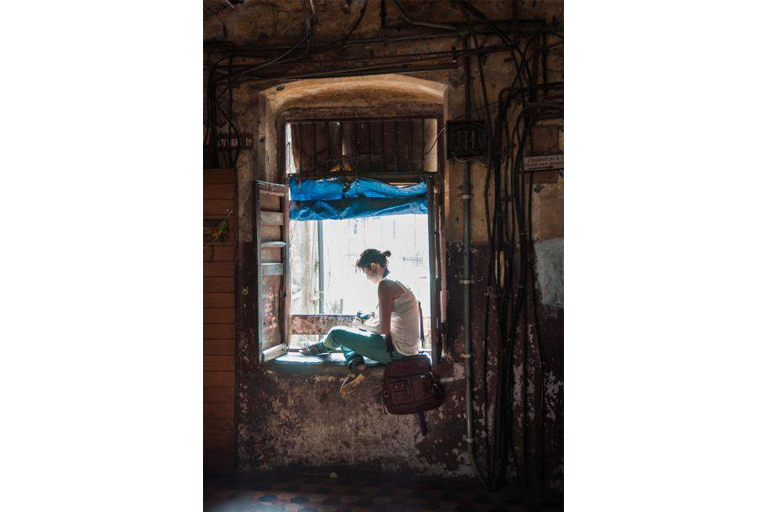

Aaliya in Ship of Theseus

Aaliya in Ship of Theseus -

Maitreya in Ship of Theseus

Maitreya in Ship of Theseus -

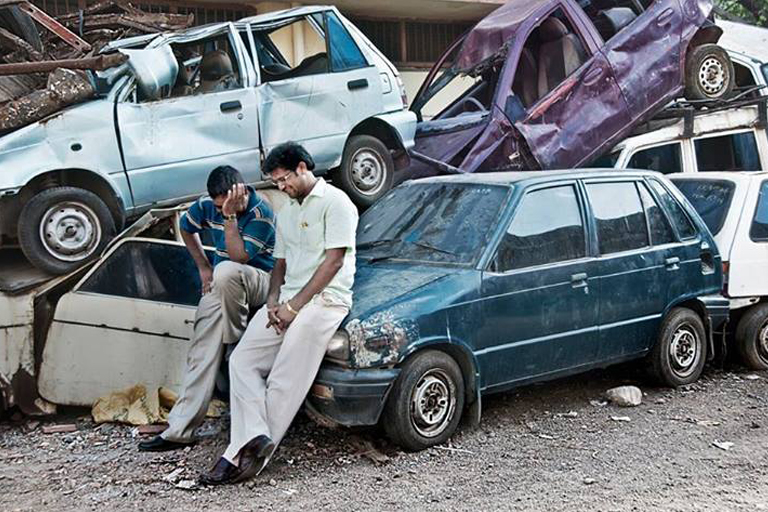

Navin in Ship of Theseus

Navin in Ship of Theseus -

A still from Ship of Theseus

A still from Ship of Theseus -

A still from Ship of Theseus

A still from Ship of Theseus

Ship of Theseus has a marked tendency: denouement by landscape.

Warning: Spoilers Ahead

The protagonist of the first segment, the photographer Aaliya, finds some sense of content sitting on a bridge over a mountain stream. In the second segment the protagonist, the Jain monk Maitreya, finds the passage to death much harder than he imagined. After nights of suffering and delirium we are signalled his decision to seek medical help (and a greater decision to return to the world) through a screen filled with lush, green fields. The wind passes through the plants and the breath of self-preservation returns to Maitreya. The protagonist of the last segment, stockbroker Navin, is accused by his activist grandmother of deliberately turning his back to the beauty and grief the world can offer. The widening of his horizons are all signalled by landscape: the cramped spaces of a Mumbai slum, the desolation of rural Sweden, the cramped spaces of a Swedish flat filled with young immigrants. When he returns to Bombay, the narrative loops like the ribbons of a Christmas gift and offers us all three protagonists in Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum at a special screening. Aaliya, Maitreya and Navin sit alongside five other organ recipients. They all received their respective organs: eye, kidney and liver from a man who had been an amateur cave explorer. They are now seated to watch some of his footage from the caves. And for the first time (well, almost— the repetitive halo light effect over characters’ heads also was painful), I found myself thinking: Oh no. And indeed a few seconds later we are heading deep into the caves with the shadow of the dead explorer holding up his camera. Denouement by landscape.

The landscapes are splendid. One can only feel enormous satisfaction from a screen filled with windmills and Quixote-ish monks in white or the rapid Gandhi-in-old-news-footage speed of Maitreya as he walks through a Bombay so beautiful it makes you feel a little bit drunk. But even the splendid landscapes can’t really disguise the on-the-nose plotting, the too-easy deployment of paradox. The blind photographer gets her vision back but is convinced that her post-op photos are not as good as the ones before. The Jain monk is fighting a case against animal testing in drugs and falls ill. How can he now consume the drugs that will make him better?

The last segment—the widening of Navin’s horizons—resists this neatness a bit. He is politically conservative but not a prude. He helps his grandmother pee into a bedpan with brisk efficiency. What makes Navin charge along to help Shankar who had his kidney stolen— particularly after he realizes that the kidney within him is not Shankar’s? Why does he decide to go to Sweden? The film doesn’t tell you and by now you are a tiny bit grateful it doesn’t. (Navin does have a wee bit of that do-the-right-thing going and who is to say when it hits people?) What did baffle me in this segment is the choice of a comic resolution for the other ethical crisis in this film.

While the monk and the photographer are given whole sequences to deal with the betrayals of their bodies and minds, the labourer Shankar’s decision to keep the money the white man has offered is easy, quick, a punch line. Navin in Sweden is stumped in his desire to begin a legal crusade on Shankar’s behalf. Navin’s friend Mannu is stuck between the narrow walls of the chawl— doing a close imitation of the Biblical admonishment that a rich man is as likely to enter heaven as a camel is to pass through the eye of the needle. Shankar is a variation of the old, hoary tradition of the comic servant. As Kantaben is ha-ha astonished by the homoerotic antics of the boys of Kal Ho Na Ho, Shankar is ha-ha fed up with middle-class justice. Unlike even P. K. Dubey of Monsoon Wedding who is allowed pensiveness and Delhi skylines, there are no widening, meaning-filled landscapes for Shankar.

*****

The ‘art objects within art objects’ can often be tricky. You are told that the heroine of the book is a fantastic poet. You read the poem offered and you are embarrassed for the character and the novelist. How can you believe the novelist anymore? When characters in movies are artists I brace myself for embarrassment. Watch out for bad water colours and pulsing Pollocks.

First films and student films have a terrible inclination to pick sex workers and artists as their protagonists. What a pleasant surprise then to see in Ship of Theseus the reasonably interesting work Aaliya produces and her actual artistic dilemma: Should I stage my work? If I just press a button to record unstaged life, am I an artist? While not the most tortuous or original of dilemmas, it is still better than the ridiculous simulacrum of artistic lives cinema usually offers. Once I made the mistake of watching Frida with a leftie from Kolkata. The moment when Frida slides with a Salma Hayek slither into Trotsky’s lap was when my friend lost her mind and left the room.

This same friend also lost her mind when a visiting software engineer flirtatiously said to her: “Oh, you are studying philosophy? My favourite philosopher is Ayn Rand.” The ‘philosophical discussions’ of Ship of Theseus do have the charming adolescent enthusiasms of an 18-year-old Ayn Rand lover. It is disguised by framing it as conversations between Maitreya and his quasi disciple, the school-boyish lawyer. I decided that the filmmaker’s way of telling us that Maitreya is a truly great man was his forbearance in not swatting at him and saying: “This ain’t moot court, bro.”

*****

On the subject of Aaliya’s work, Bombay is home to a whole school of blind photographers trained by photographer Partho Bhowmik. Bhowmik was inspired, he told me once, by Evgen Bavcar whose elaborate, costumed and plumed work Aaliya was sure to have liked.

TBIP Take

OpinionJuly 2013

By Nisha Susan

By Nisha Susan

Nisha Susan is a writer and critic based in New Delhi. She was Features Editor at Tehelka magazine and has worked for several non-profits. Her short fiction has been published by Penguin and Zubaan and she's currently working on a novel and a book on Malayali nurses. Her expectations of cinema were permanently raised from watching pulp films as a three-year-old in her grandfather's village theatre.