-

Hana Makhmalbaf

Hana Makhmalbaf -

Hana Makhmalbaf

Hana Makhmalbaf -

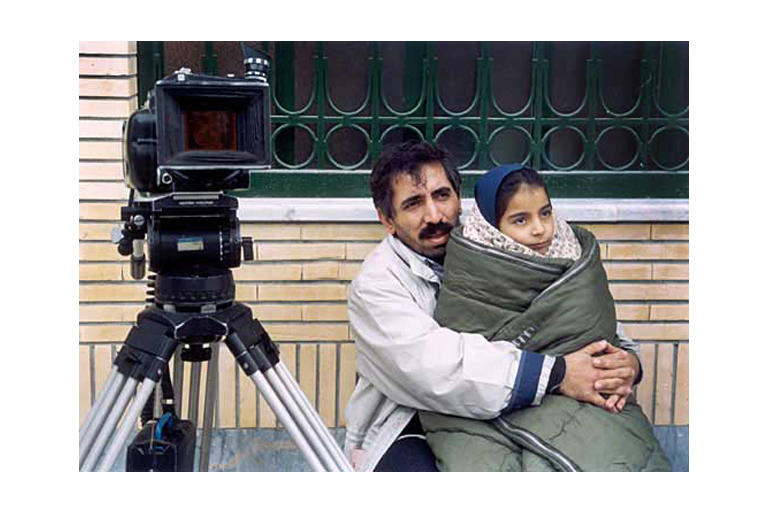

Hana with her father Mohsen Makhmalbaf on set

Hana with her father Mohsen Makhmalbaf on set -

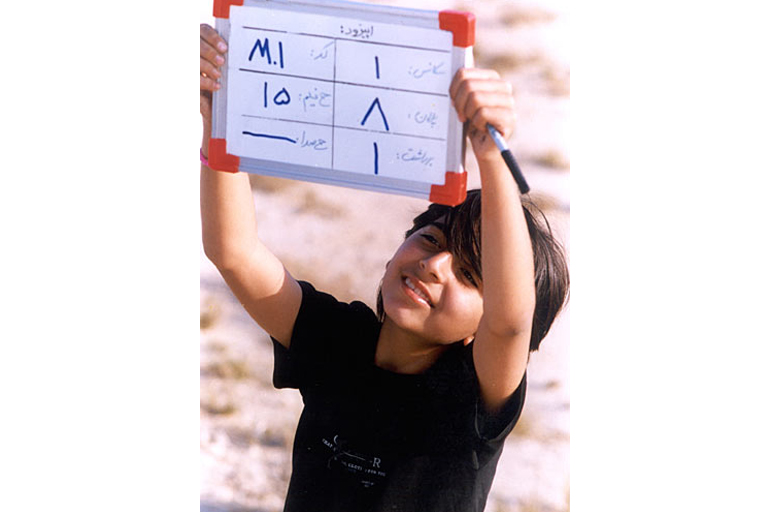

A young Hana holds up the clapper on the sets of her father's film

A young Hana holds up the clapper on the sets of her father's film -

Poster for The Day My Aunt Was Ill, directed by Hana when she was 8

Poster for The Day My Aunt Was Ill, directed by Hana when she was 8 -

A still from Buddha Collapsed Out Of Shame, Hana's first feature

A still from Buddha Collapsed Out Of Shame, Hana's first feature -

A still from Green Days

A still from Green Days -

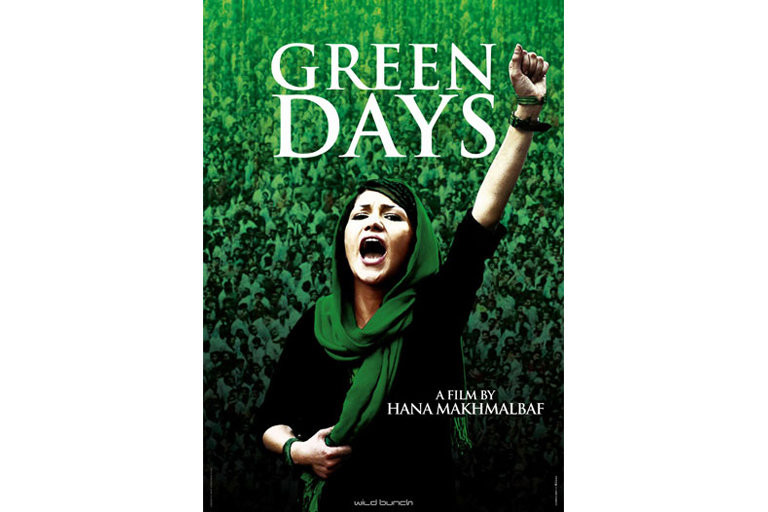

Poster of Green Days

Poster of Green Days

Hana Makhmalbaf, 24, wears her conviction on her sleeve quite comfortably. Her ‘manto’, or Iranian overcoat, is a constant reminder of her homeland and, consequently, the suffering of her countrymen. And yet, she is equally interested in places and people outside of her country’s borders. Her films reflect the emphasis she places on looking at people of various nationalities as “humans first”.

Born in a family of filmmakers, daughter of acclaimed Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Hana’s career in filmmaking began early. Some would say too early. At the age of seven, she acted in her father’s film ‘A Moment of Innocence’. When she was eight she started studying films at the fabled Makhmalbaf Film School. The same year she made her first short film, ‘The Day My Aunt Was Ill’. Her documentary, ‘Joy of Madness’, made when she was 14, premiered at the Venice International Film Festival and won the Special Jury Prize at the Tokyo Filmex, 2003. Her first feature, ‘Buddha Collapsed Out Of Shame’, was also critically lauded, winning the Special Jury Prize and the TVE La Otra Mirada Award at the San Sebastian International Film Festival. The film also won the Crystal Bear for Best Feature Film and the Peace Film Award at the Berlin International Film Festival. In 2009, Hana filmed the protests in the run-up to the Presidential elections in Iran and went on to make the docu-fiction ‘Green Days’.

What was it like growing up in the Makhmalbaf family. You are all filmmakers. What is it like, with all of you working around films? Do you discuss your work often?

Yes I was born in a family of filmmakers. My father is a filmmaker. My mother was always helping him make films. So most of the time, in my family, we’re talking about cinema. Even when I was a child. Even my games were about cinema. So it was always like that.

What kind of games?

I remember, for example, when I was 8 years old I made a film. The name was The Day My Aunt Was Ill, which was kind of a game because my family, they left me at my aunt’s house. So I started directing my cousins and it became a film because it was, kind of, all the games I knew.

How much of an influence has your father been in your personal journey as a filmmaker?

I was born in this family. I’ve lived with him for 24 years. I worked with him. He was my teacher. He has been my favourite filmmaker. I became a lover of cinema because of my love for him. Sometimes when I talk, I think it’s him inside my head talking. But of course, everyone has their own way of… I have been so influenced by him but it’s not like I am totally him. It’s like two different people, but of course I learned a lot from him.

When you are making your own film, do you consciously work towards achieving your own style?

It’s not that you decide to have your own style. I’m a different person. I don’t everyday decide to look like Hana, but it’s how I have been created. It’s me. I didn’t decide for a different face from my father but it is different. So my character, the way I make a film, the way I write, the way I talk, they are all different but there are some similarities at the same time. It’s not something you decide. Say, you give the same script to me, I’ll make it differently, my father will make another film from the same script and my sister (Samira) will make another. Because we are different. For example, I have grown up in a family with my sister (Samira) and brother (Maysam), we have all learnt the same classes, we have lived in the same atmosphere, but my sister, my brother and me we are completely different people. My sister is much more philosophical. My brother is more technical, more ‘new generation’. I am somewhat in the middle of both of them.

Did you study at the Makhmalbaf Film School? What is the style of filmmaking that is taught? I have read that it is different from what normal film schools teach. How is it different?

It was different. It doesn’t exist anymore. It was there for six, seven years. There were three kinds of classes in our school. The first group of classes was on how to live better, because my father believes that a good filmmaker is a person who can live alone for a long time and can live well. In those classes there were cooking, riding, bicycling, swimming— everything to make ourselves stronger. Like, I remember, my mom couldn’t bicycle at all on the first day. After the seventh day, she bicycled 52 km around an island. So a filmmaker should be strong because he or she has to stand on his or her knees from 5 am to 6 pm. We don’t sleep. So it is something to make us strong.

The second set of classes was all towards becoming a better human being; because being a filmmaker, it’s not just to make films, it’s to make films that change the world, it’s to be a better human. So those kinds of classes we had, like philosophy classes, psychology classes— it was also to find subjects and ideas from these classes. We had sociology and also we had Sufism, which I remember was in the beginning of these classes. We started to learn that these people (the Sufis), they had nothing. For example, they were forsaking everything they had. And then, at the end of the class, we were even giving away our own books, to learn how to give away.

So the third kind of classes, they were about cinema. We learnt everything about the technical parts of cinema, analyzing cinema, editing, photography, cinematography, being a DOP (Director of Photography), everything which is involved.

Do you think this style of learning filmmaking is something that can be taken out from amongst the family and given to others to learn as well?

Actually when my father started this film school, he asked permission from the government of Iran to allow him to open the school publicly. But they said, the government said, “One Makhmalbaf is enough for the whole country, we don’t need one hundred like him.” But, anyway, some of our friends, some of our family, and our relatives started with us. But they were such difficult classes. We were working, sometimes, for 16 hours per day, we were studying for 16 hours per day. I remember I was 10 years old… I was in the philosophy class eight hours a day and everyone was telling my dad, “She doesn’t understand it.” My dad was saying, “Even if she gets 20 percent of this class, or 10 percent, at this age… if she gets it, it will stay here (indicates her head) like the structure of her mind. But if she studies it later, even if she gets 100 percent, it will only be a part of her mind.” So it was so difficult, the classes. Some of the students left, later. Some of them attended only some classes, like scriptwriting— and they became scriptwriters. Some of them attended composition class and became photographers. A few students came along with us (her and her family), to be filmmakers, and are now filmmakers, like Mohammed Ahmadi and some other friends. But the first rule that my dad put for this ‘university’ was that no matter what you do, it doesn’t matter, the only rule was that everything you want to do, even swimming, you have to do it eight hours per day minimum and for a minimum of one month. So even if you didn’t know how to swim in the beginning, if you did it for eight hours a day for one month, after one month you were a trained swimmer. So you became professional. That was the only rule that we were following.

The first film (The Day My Aunt Was Ill) you made was when you were eight. What were you thinking when you came up with the idea? Did you have a conscious thought?

Filmmaking for me is not like a job. It’s not like a business. It’s love or passion. And when I was eight years old of course it wasn’t the way cinema is now for me. It was a pure love. But for that, I remember, the main idea came from a photo that I saw in an exhibition. There were a bunch of children painting on the floor and the photo was taken from up, from a top angle while the children were painting. And the next day, my parents, they left me at my aunt’s house to visit some festival… I don’t remember. And then my aunt got ill and she went to the hospital and we were with my grandfather. So we started to play and the idea I gave was this painting. But little by little, my cousins that were there as well—my brother was my cinematographer—they started to become jealous of each other. So because I was influenced by films from my dad’s kind of cinema, I said let’s bring it all in front of camera and, as you can see in the film, I’m directing them in front of the camera and the ‘behind-the-scene’ and the ‘scene’ itself is mixed, and it’s shot that way because my brother was shooting all of us.

You shot the making of your sister Samira’s film.

I made a film called Joy of Madness. It’s a documentary film about her casting in Afghanistan. It was the casting of At Five in the Afternoon. But actually, though it was supposed to be a behind-the-scenes, it turned out in another way because, when she was trying to cast people, for one month everybody was afraid of her, everybody there didn’t want to act in the film. They were afraid of cinema, they were afraid of everything— their burqa, the Taliban, everybody. So I decided to change the subject of the film to the fear of Afghan women in general.

Because of the acclaim you get as a family of filmmakers, and for your own work, do you feel that somewhere you are representatives of your country politically, outside of the country?

It depends on what film I’m making. If it’s on Iran, of course I’m representative of Iranian people. But before anything else, I think I’m representative of human beings— whatever pain they have that I’m talking about. Then I’m representative of that. Of course, I will never forget my people in my country and the suffering they have. I always wear my manto, even when I’m outside of Iran, not to forget their pain. But I think we have to take off these borders that we put mentally for ourselves and think of the human being first and then think of women… then anything else that comes after.

But do you feel, when you go around making your film, that somewhere people expect you to explain the politics of Iran to them? Be a representative of that side of Iran to the world outside?

Actually I have made Green Days which is a docu-fiction film on the election in Iran. It was about exactly the same problem because, some of the people— they wanted to vote but they weren’t political people. American people, Indian people, they go to vote and none of them get killed for what they voted for. But people, normal people, very ordinary people, they went to vote and then the next day they got killed. They weren’t political but they got killed because of political reasons. That’s why in my country, everything at a point became political. The government brought politics inside people’s houses and it’s not something you can forget. You have to manage to live within it every day. Even the religion is political, is something that the government puts on you. Even my clothes… it’s something (clothes) that the government puts on people. So yeah.

Personally, what are you trying to explore as a filmmaker?

Everything you do in life, you are exploring it and going deeper and deeper. At first it’s a question for yourself, and then it becomes an idea, then it becomes the script, then it becomes the film. But when you go all the way back, it was a question that started it, and you want to put this question clearly in front of the society. That’s why you start to make that film.

For example, Buddha Collapsed Out Of Shame— it was a question for me at the beginning: What will happen to these children who are all in front of us? Then I was going and staying with my mother, who was a scriptwriter. Staying in the middle of Afghanistan in Bamiyan city. Then, little by little, I was seeing what was happening and that was the journey you can see in the film. This thing that you see in the film is the journey that I went through and that is the fruit of all the exploration. (The film is the story of a five year old Afghan girl attempting to attend school. It is set in the Bamiyan valley where the statues of the Buddha were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.)

A scene from Buddha Collapsed Out Of Shame:

Are you working on anything right now?

I edited a short film of my dad’s and I produced a film for him. But making a film, as I said, is not a business for me. So I don’t make anything unless it touches me. It has to be something that I want to say. There is a pain that I feel and I say, “Oh my god I want to say this, and I know I can say it.” So I’m looking for that pain that I want to show to the world.

Iranian cinema has become very prominent in the world. How aware do you think the people of Iran are, generally speaking, of the significance their cinema?

Actually, 30 years ago, before the (Islamic) Revolution, we were making about 70 movies a year. Because of the Hollywood cinema in our country, because of the competition between Iranian cinema and Hollywood cinema, Iranian cinema was losing out, because people wanted to watch those (Hollywood) films. Then, after the Revolution, they banned the Hollywood films. Then Iranian cinema had to make its own films for its own people. So again the industry produced almost 70 films per year. And when the films started going around the world because of the New Wave in Iranian cinema, the poetic realism that was inside them, Iranian cinema won some two thousand awards, one hundred of them being won by just my family. All the Iranian people, they were interested in this even though they weren’t very interested in artistic cinema. They were saying, “Let’s see what we are proud of. Let’s see why we are attracting attention.” So they started watching such films and then they realized, later on, what this cinema was.

A lot of these films, including your family’s films, are banned in Iran, or censored. How do you see filmmakers combating that? How do you get those films across to your own people?

Eight years ago, eight films from my family were banned and six years ago all them were banned. Everything. Even our name is banned in Iran. But all our films are in the black market and they are available in the best quality. For example, my last film Green Days, the day it was shown at the Venice Film Festival, on its premiere, I decided to show it on BBC Persia to the Iranian people as a gift, so they could see it at the same time as the world premiere, on BBC Persia. So that’s the other way at this point. And the black market. Because of the people’s interest they go and look for it and find it.

A scene from Green Days:

“Even our name is banned in Iran.”

InterviewAugust 2013

By Meryl Mary Sebastian

By Meryl Mary Sebastian

Meryl Mary Sebastian is Junior Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture