-

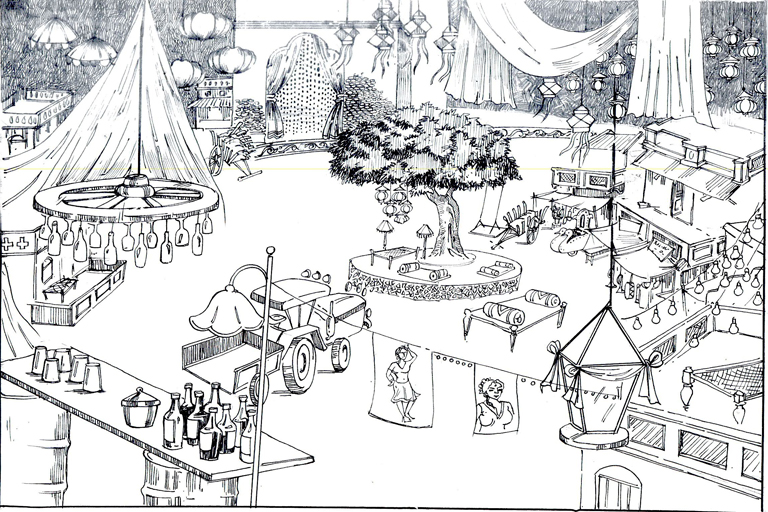

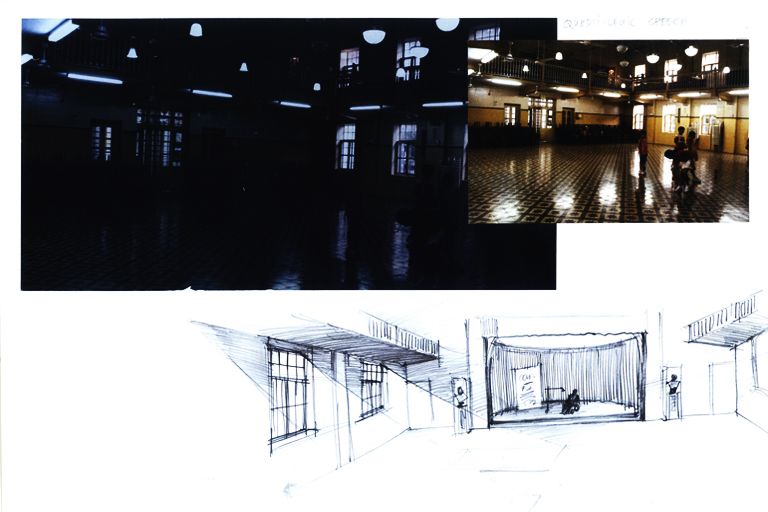

Visualisation sketch of a set from Dabangg, used in the Munni Badnam song, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan

Visualisation sketch of a set from Dabangg, used in the Munni Badnam song, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan -

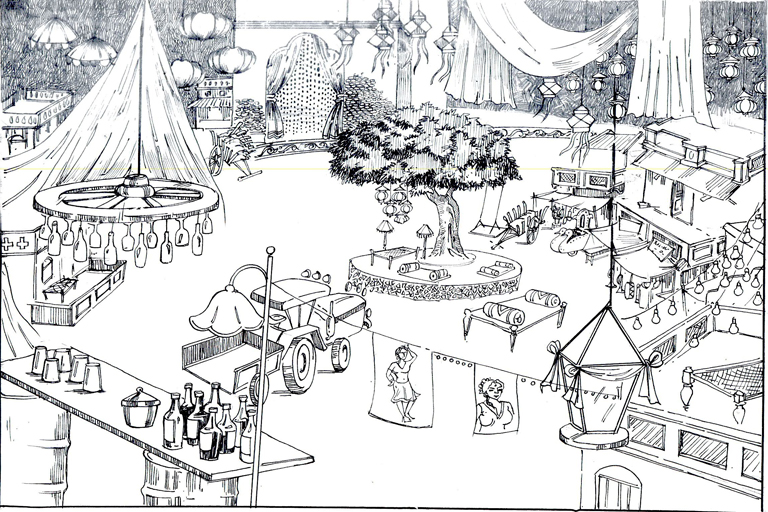

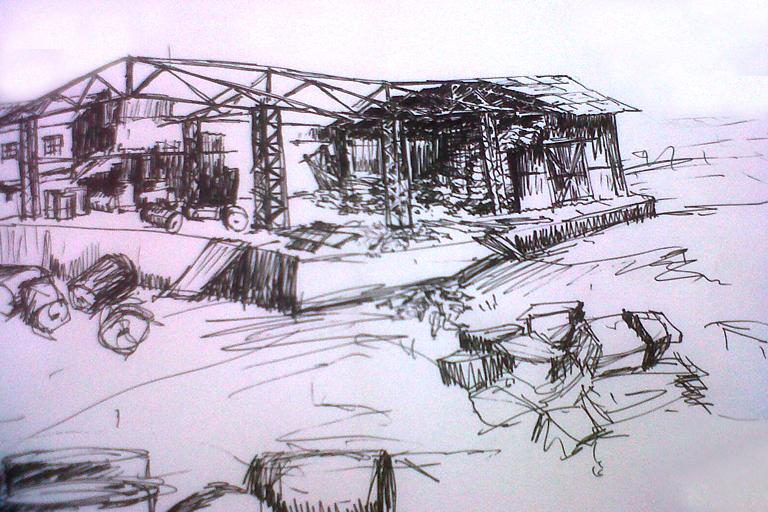

Visualisation sketch of a liquor factory set designed for Rowdy Rathore, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan

Visualisation sketch of a liquor factory set designed for Rowdy Rathore, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan -

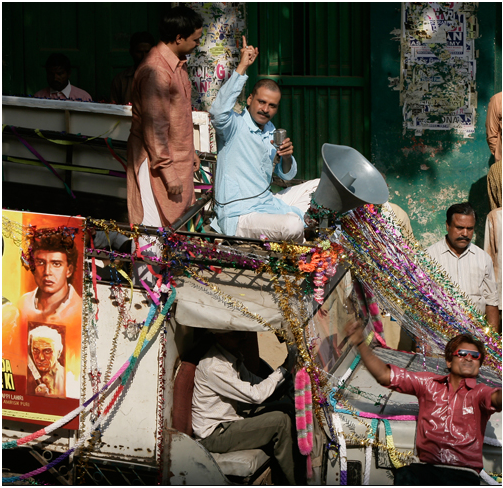

A set from Rowdy Rathore, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan

A set from Rowdy Rathore, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan -

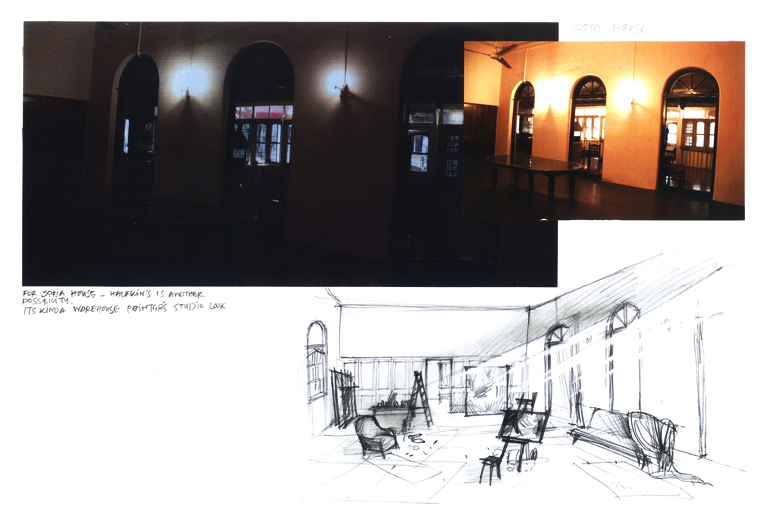

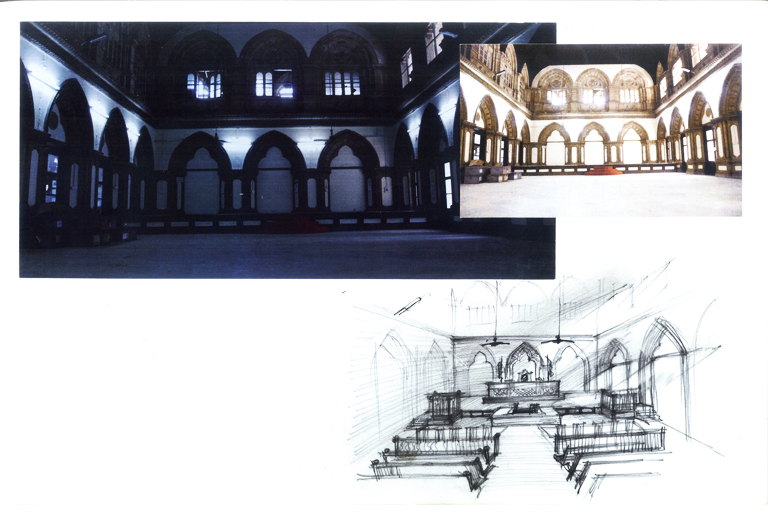

Visualisation sketches and a set from Guzaarish compared, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan

Visualisation sketches and a set from Guzaarish compared, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan -

Visualisation sketches and a set from Guzaarish compared, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan

Visualisation sketches and a set from Guzaarish compared, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan -

Visualisation sketches and a set from Guzaarish compared, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan

Visualisation sketches and a set from Guzaarish compared, Courtesy Tariq Umar Khan -

Visualisation sketch of a set from Lamhaa

Visualisation sketch of a set from Lamhaa -

On the sets of Lamhaa

On the sets of Lamhaa

Deepanjana Pal on the relevance of art direction in Hindi movies and trends in the profession, from the fifties to now.

On November 5, 2011, at the art gallery Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, set designer and filmmaker Aradhana Seth made her debut as an artist with a show titled Everyone Carries a Room About Inside. The gallery was turned into an imaginary house, but not one that would belong in the pages of a magazine. This was a house made up of rooms that were sketches. They filled the space with objects that had been flattened to fit into bold, wavering lines that had the unsteady quality of drawings done by hand. Every element— even the clutter—seemed artfully arranged. Despite the fact that Seth’s paintings were filled with everyday details, they felt entirely unreal. Perhaps Seth wanted her audience to be surrounded by artifice as they saw her show, but the paintings looked like clumsy representations of reality and the effect was to make the gallery seem like an awkward experiment. What Seth had created wasn’t a home; it felt like a set.

Ironically, when Seth designs films, the effort is to communicate precisely the opposite effect. No matter how removed from reality the story may be, it falls upon the art department and production designers to create a world that makes the film credible to the viewer. Would a train compartment ever look as plush as the interiors Seth created for Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited? It is highly unlikely, but for a film set in the off-kilter universe of Anderson’s stories, the rich colours and elaborate patterns (even the bunks looked like they were covered in hand-painted fabric) were perfect. This was an India crafted largely out of Anderson’s imagination: precious, beautiful, slightly retro, and about as similar to Rajdhani compartments as frozen yoghurt is to shrikhand. There’s nothing realistic about it, but the sets establish the reality in which the film is set.

Sacrilegious as it may seem to put Anderson and commercial Indian cinema in one sentence, the fact is that both of them sell you an alternate reality in the way their worlds are presented to the audience and how their stories play out. The first, most crucial step in that process is the production design. In the intensely collaborative world of filmmaking, the art department is like the group of nocturnal elves in the fairytale about the shoemaker who would wake up in the morning to find perfectly-made shoes that seemed to have appeared in his workshop magically. Few of us watch a film and applaud the people who created the sets in which the actors perform. Yet, before an actor has even entered the frame, the storytelling has begun as the camera shows you a space. A good art director lures us into the world of a film, persuading us to suspend our disbelief for the next couple of hours, as the most improbable events unfold on the screen before us.

For instance, few of us have questioned just what kind of architecture would allow Mogambo of Mr. India to have a bubbling pool of lava right below his floor. But art director Bijon Dasgupta made it seem perfectly logical that a sliding panel would be protection enough. Then there’s the staircase, which is a prominent architectural feature of almost every wealthy home in Bollywood. Disapproving fathers in shiny dressing gowns, and villains, need staircases to direct their glowering gaze at the hero or heroine at a suitably-sharp, downward angle. Many a character has stumbled to its death because of it. The staircase is also the site of whispered sweet nothings as the lead romantic pair make their way down to a party or a wedding. It is a silent but key player in so many stories, yet it doesn’t occur to us that few people choose to have staircases in the middle of their living rooms.

The production design team is key to rendering a director’s visual style distinctive. The elaborate grandeur that is Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s trademark can also be attributed to art directors Nitin Chandrakant Desai (Khamoshi, Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam, Devdas), Omung Kumar (Black, Saawariya) and the team of Sumit Basu and Rajnish Hedao (Guzaarish). The gritty glamour of Anurag Kashyap’s best work has been made possible thanks to Wasiq Khan in Black Friday, Gulaal, That Girl In Yellow Boots and Gangs of Wasseypur, Tariq Umar Khan in No Smoking and Helen Jones and Sukant Panigrahy in Dev.D. And the glossy gleam of a Karan Johar film has become synonymous with art director Sharmishtha Roy who has worked on every film of his. The aesthetics of these filmmakers are instantly recognizable because of their production design. The art department translates the director’s vision into the style of the film. It also determines its genre. Film noir, for instance, is a theme that ensues as much from the production design of a movie as from its camerawork or script. Small wonder then that director Biren Nag, who made two of the better known films in this genre in India—Bees Saal Baad and Kohraa—was art director for 1950s Indian noir movies like C.I.D., Kala Pani and Detective before he became a filmmaker.

On the other end of the spectrum, for Johar’s dramatic love story Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, released in 2001, Roy re-created Delhi’s Chandni Chowk in Mumbai’s Film City as a hygienic, sanitized and kitschy mohalla with old world charms to woo a nostalgic diasporic audience. For Delhi-6, Rakeysh Om Prakash Mehra’s production designer Samir Chanda created another type of old Delhi in Sambhar, a Rajasthani town that had similar architecture. It was just the right amount of clutter and chaos to make the sets seem authentic, but it didn’t overwhelm the frame. It provided a mix of realism and spectacle for a blockbuster attempting to deliver a message and a hit. “I created a background plate and punched Jama Masjid into the frame,” Chanda said in an interview. “In the old days, I would have called in a background painter and made a cut-out. Now there is this technology, which allows it to be punched in during editing.”

Back in the era before fancy special effects, to show the story has shifted to a hill station a painted backdrop with mountain peaks would appear on camera and sweater-clad actors would stand in front of it. A friend of mine remembers his parents’ house in Kolkata frequently being used to show the rich father’s den where the poor but idealistic hero would be invited, offered some alcohol, and then humiliated.

But, mostly, movies were shot in the studios. In 1958, for instance, when the tricks of the trade were far less sophisticated, director Shakti Samanta imagined Calcutta as a city of shadows and crime in Howrah Bridge. The film’s soundtrack had a number of memorable songs, including Geeta Dutt’s Mera Naam Chin Chin Chu. The song was one of Helen’s first hits and Art Director Sant Singh set it in a bar that has shiny, mosaic walls and fluttering white curtains. There are paintings on the walls to add richness to the ambience. The song actually begins with a shot of a light fixture—a revolving affair that dangles from the ceiling—and as Helen twinkle-toes her way across the room, singing the song, you can see European art-inspired sculptures of nubile women in the background. All the little details of the decor convey to us that this is a stylish place. The bar was probably an easier task for the art department than recreating the metallic pillars of the real Howrah Bridge and it’s unlikely that anyone even in 1958 believed that Samanta had shot on location or that a bar like the one in which Helen sang that famous ditty actually existed. For the duration of the film though, this fictitious Calcutta replaced the real one and this noir city felt as accurate as anything in a newspaper report.

Fourteen years later Samanta directed Amar Prem, a love story that called for a romanticized representation of Calcutta. The song Chingari Koi Bhadke appears to be sung by Rajesh Khanna to Sharmila Tagore on a quaint nouka, or boat, on the Hooghly, but was actually shot in Mumbai’s Nataraj Studios. A soulful and richly sentimental Kolkata was depicted by recreating the river, on which shimmered the reflection of the city’s night lights. As the nouka sways to the rhythm of the melody, Khanna reaches out, melancholically, to touch the water. Many years later, Tagore recalled in an interview that the water in the studio was stagnant and dirty and stank through the shoot. “It was horrible,” she said. “But on screen it looks like poetry.” But more than making the Hooghly prettier than it actually is, what Samanta’s Art Director Shanti Dass had captured was the ambience of the city and the setting in which the film was set.

Over the years, the budgets for films have become bigger, and more attention is paid to production design because cutting costs in this area makes the entire film look amateur. The work of the art department now also determines how sophisticated the film will be deemed. Whereas in the past the frame would usually be tight, focusing on just a small patch of wall or a corner, now an entire area is created to allow for wider shots. Film sets no longer look like temporary constructions. Take the family home as seen in Rajshri Productions’ films. The two-tiered structure that housed the happy family in Hum Aapke Hain Koun, or the roof where Bhagyashree appeared before Salman Khan (but not the audience) in a nightie in Maine Pyar Kiya were almost theatrical. In the more recent Vivah, on the other hand, the homes don’t look like they’re made of plywood panels that were taken apart at the end of the shoot.

Today, much like the saying about Mohammed and the mountain, frequently the art department and production designers have the responsibility of creating miniature versions of entire cities in studio complexes like Film City which is spread out over 500 acres in Goregaon, Mumbai. For Lamhaa, a hard-boiled political thriller, Wasiq Khan brought in two truckloads of chinar leaves (among other things) to recreate Kashmir in Film City. Bhansali is known for creating beautiful but overwrought sets that are frightfully elaborate. His production designer Omung Kumar built parts of pre-independence Simla in Film City, Kamalistan and Mehboob Studios for Black. Then, for Saawariya, he created a faux-city, complete with lakes, streets, shops, signage and a clock tower, that was unmistakably but beautifully fake. Whether it be Devdas or Saawariya or Guzaarish, Bhansali’s vision is the stuff of spectacular fantasies, which must be realized by his art directors. When you see the gorgeous stills for Bhansali’s films and find yourself charmed enough to buy a ticket, it is the art director whose spell you’re under. It is he, or she, who creates a critical aspect of the spectacle that is film.

Mumbai’s Film City had setups built so that one could film everything from a temple scene to sequences set in a village or mansion within the radius of a few kilometres. These structures appear as recurring motifs in opuses of the past, but are dismissed today by modern Hindi filmmakers for being too tacky. A scene from Deewar, Yash Chopra’s 1975 release that had Amitabh Bachchan exhorting a statue of Shiva, may have immortalized the Film City temple, but it would be impossible to imagine Yash Raj Films shooting a scene there today. Nowadays Film City’s permanent sets are mostly booked either by Bhojpuri filmmakers or TV show production houses.

It’s not that the temple is no longer important, but that it’s been given a makeover now that Bollywood has become more ambitious in terms of its preferred locations. For Aditya Chopra’s Mohabbatein, Bachchan’s comeback vehicle in 2000, Sharmishtha Roy had to create a Shiva temple on the grounds of Longleat House, a palatial and stately home in the English county of Somerset. This is characteristic of another trend that followed the age of the studio set: that of shooting on location. Who can forget how much director K Asif invested into filming the song Pyaar Kiya To Darna Kya from Mughal-e-Azam at Lahore Fort’s spectacular Sheesh Mahal or filmmakers like Raj Kapoor and Yash Chopra’s fondness for shooting in exotic foreign locales?

Shooting on location didn’t mean the art department’s work lessened. For Kabhie Khushi Kabhie Gham, made by Karan Johar, one of Yash Chopra’s aesthetic successors, Amitabh Bachchan’s character’s family home was to be set in Waddesdon Manor. As in Mohabbatein, Roy had to install a mandir to recast the Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild’s chateau as the house of a mysteriously über-rich Indian industrialist. With shooting abroad becoming de rigeur, the art department’s task has become increasingly more elaborate. New York in Karan Johar’s Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006) has been described by The New York Times Critic Neil Genzlinger as the place where “rainstorms are a little rainier than real life; the wind machines are cranked up an extra notch.” It was also where Rani Mukerji, in an effort to be the average NRI housewife as imagined by Johar, vacuumed her house—which looked like a pristine service apartment—wearing a figure-hugging dress that would be perfect for a cocktail at a posh bar. Both Kabhi Alvida… and Rensil D’Silva’s Kurbaan, released in 2009, had scenes that were set in New York but actually shot in Philadelphia. It fell upon the production design team of these films to make sure the city known for cheesecake looked like the Big Apple to Indian viewers. Fortunately for most Indian audiences, one American city looks much like another. Those familiar with Philadelphia may have wondered how its 30th Street subway station popped up in New York City, but for most viewers, a picturesque cityscape with shiny high-rises and Caucasian pedestrians are enough. The art department’s role here comprised more of avoiding elements—such as signage—that were typical of one city rather, than inserting those typical of another.

Desai, art director for Bhansali’s earlier films, also created the village of Champaner for Lagaan, which was shot in Gujarat but was no less fabricated for being an outdoor shoot. He and his team enlisted the locals to build one temple and 56 huts for the film. Some of these huts were modelled upon ancient Kutchi huts, which were circular in shape. It’s another matter entirely that the film’s dialogues were all in Avadhi, which has no trace of Gujarati.

The latest trend in Bollywood seems to be rustic small town India. Vishal Bharadwaj set his Othello-inspired Omkara in India’s heartland in 2006 but the places we’ve seen in films like both the Dabanggsor Ishaqzaade or Rowdy Rathore or Barfi or even, in parts, in Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani are very different from Bharadwaj’s chosen canvas. Dabangg is part of a trend that celebrates camp in all its comic book glamour. A stylized small town by Wasiq Khan (a production designer who was till this movie known for gritty realistic cinema like Aamir and Black Friday, and who has since created sets for Rowdy Rathore and Ranjhanaa) adds to this effect. In contrast, Yash Raj Films’ Ishaqzaade production designer Mukund Gupta merely aggregates kitsch from the reality of small town India to stitch a technicolour dreamcoat for Habib Faisal’s love epic to flaunt. But in all these films small town India is a photogenic, doll’s-house-esque version of itself that can obligingly crumble and explode to make the hero look larger than life. Unlike Bharadwaj’s non-urban India, which seems to be densely-packed with problems, the new India shown on celluloid is depicted as a simpler world. It doesn’t have the chaos or the distractions of cities and is an idealized version of the B-town. The colours are warm, the setting is a mix of rustic and modern. Here, in its prettily-decayed buildings and modest homes, the problems of urban India are dealt with summarily. Fights that make walls cave in provide solutions. Systems can be put in place here and some properly old-fashioned ideas of love and romance can be enacted.

Till recently, to woo audiences, Indian films showcased, for the main part, an urban world that viewers could aspire to. This world was set in India and abroad, in cities like Mumbai, New York and London, across slumlands, Tudor houses and street cafes. The exotic was sought out in countries like Latvia, Morocco, Spain, Denmark, Sweden, Jordan, Russia, Peru, Brazil and Seychelles. Even Kenya, Namibia and Afghanistan. Tashan, set across small town India, had a song filmed in Milos. Ajab Prem Ki Ghazab Kahani, a campy love story at a hill station, had songs shot in various parts of Turkey.

Today our gaze seems to have turned towards the great Indian hinterland. This means that now the art director must fashion this other India as a slick, photogenic product that can be served up as ‘cult’ for an urbane audience that would like to believe it has more in common with Quentin Tarantino than Karan Johar. Consequently, there’s a quality of wink-wink-nudge-nudge cleverness in the design of these films. For example, the poster for Gangs Of Wasseypur showed another film poster— that of a 1984 Mithun Chakraborthy film (with the name misspelt), Ksam Paida Krne Waleki. These quirks are ‘in’ jokes for those who get the genre. For those that don’t, these films are masala potboilers, straight out of the 1980s, and can be enjoyed all the same. Some of these films are made by and intended for those who regard the audiences that create box-office hits with a degree of contempt, while trying to appease them all the same. Perhaps the divide between the haves and have-nots has become so wide that it cannot even be bridged in the escapist fantasies of cinema.

Places Other Than This

ArticleSeptember 2013

By Deepanjana Pal

By Deepanjana Pal

Deepanjana Pal is an author and journalist based in Mumbai. She has written a biography of the artist Ravi Varma, titled The Painter. She’s a Senior Editor with Firtspost.com. Previously, she handled the Art section of Time Out Mumbai and was Books Editor at DNA. Her writing has appeared in a variety of publications including Wallpaper*, Caravan, Time Out London, Frieze Magazine, Business Standard, Tehelka, Mint Lounge and ArtSlant. The first film she saw in the theatre as a kid was Silsila. Apparently, she watched the whole thing without saying a word and, when leaving, told her parents that the ending wasn't very good.