-

A still from Oonga

A still from Oonga -

A still from Oonga

A still from Oonga -

A still from Oonga

A still from Oonga -

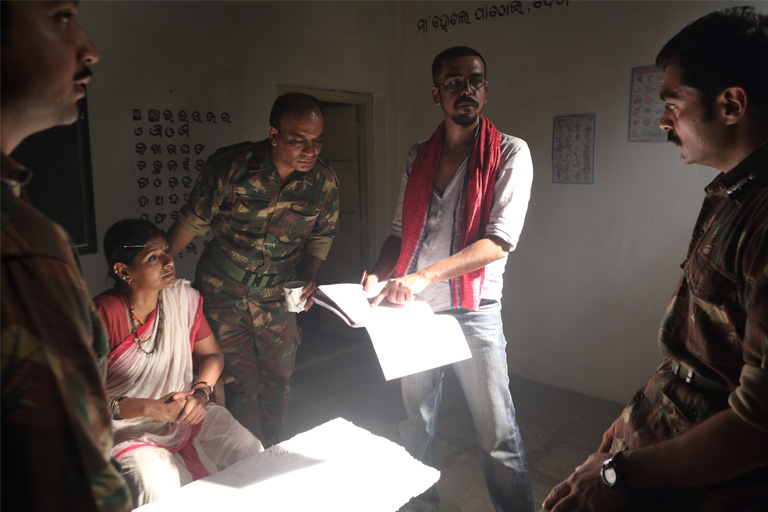

Devashish Makhija on the sets of Oonga

Devashish Makhija on the sets of Oonga -

A still from Oonga

A still from Oonga

A new film that tries to get to the heart of the crisis of the tribals, development and the Naxalite-Maoist insurgency.

In a dream that came to her about four decades ago, filmmaker James Cameron’s mother saw a 12 feet tall blue humanoid. In 1976 Cameron inserted this into his first screenplay, a science fiction spread across several planets. In 2009 we saw it on screen in his epic Avatar. “There’s a connection to the Hindu deities, which I like conceptually,” added Cameron, about why he decided that the Na’vi, a humanoid species indigenous to a fictional planet aptly titled ‘Pandora’, a more ‘primitive’ species in some ways—who, with just bows and arrows, fought the humans (equipped with powerful missiles) who wanted to displace them to plunder their land for a mineral—would be blue-skinned.

In 2010, when Devashish Makhija was in Koraput, Orissa, Sharanya Nayak, the local head of ActionAid (a poverty fighting NGO), told him about how she had taken a group of adivasis to watch a dubbed version of Avatar. “They hollered and cheered the Na’vi right through the film as if they were their own fellow-tribals fighting the same battles they were,” is what Makhija remembers Nayak telling him. This sowed the seeds of Oonga, Makhija’s first film, which will premiere in India at the Mumbai Film Festival this year.

Makhija “couldn’t get permission to use Avatar”. So he chose the Ramayana instead. The film revolves around the story of an eight year old adivasi boy, Oonga (Raju Singh in what will easily be among the best performances of the year), who has missed a school trip from his village to a nearby town to watch Sita Haran, a play based on the epic, and so he decides to undertake the journey himself. Ram, who Oonga has heard so many tales about, is his hero and his inspiration.

The only popular blue skinned ‘Hindu deity’ is Vishnu, whom religious texts describe as having the “colour of water-filled clouds”. One of his avatars, Ram, has had many an incarnation of his own. The god has travelled in time, from being the subject of India’s first great epic to lending his name to Mahatma Gandhi’s vision of an ideal state, or Ram Rajya, to, in more recent times, tragically, being reduced to a mascot for Hindu extremism. Oonga turns this last idea on its head. It resurrects Ram not as an emperor, but a forest dweller who had to fight, with an army of ill-equipped vanars—also forest dwellers—a powerful king who abducted his wife. A Ram who may have been more than a little upset with mobs demolishing other places of worship, ransacking homes and raping and murdering members of a minority community in his name.

While Oonga travels across the countryside to watch this Ram, parallel tracks play out. His village Pottacheru is in risk of being displaced entirely by a bauxite mining company. Naxalites camped nearby are ready to wage war on the state machinery once the villagers are on their side. They wish to use the village teacher Hemla (Nandita Das) to achieve this. She doesn’t wish to side with them but is suspected by the CRPF (Central Reserve Police Force) of being a Naxalite herself.

Most of what is shown in the film is based on real incidents Makhija has witnessed or heard or read of. The character of Hemla was “inspired in part by the case of Soni Sori (the adivasi school teacher from Dantewada, Chhattisgarh, who was arrested, on flimsy evidence, for being a suspected Maoist)”. About a fortnight before they were to film her abduction, in Koraput, Orissa, an adivasi MLA was actually kidnapped from a spot very near to the location for the planned shoot.

A lesser known story about the CRPF in these parts is that many of their recruits are tribal youth from states other than the one they have been posted in, who have themselves been dispossessed of their land due to industrial or mining activities in their native places. Makhija brings this out through the back-story of one disgruntled CRPF jawan’s character.

Then there are the details. “Do you know what Naxals make their moving targets wear during target practice?” asks a CRPF jawan of another when he’s about to travel around the area in his uniform.

But the film’s greatest strength, besides its cinematography (Jehangir Chowdhury’s camerawork explains exactly why the adviasis are so terrified even at the prospect of losing their beautiful land), is its language, or languages. Oonga is in Oriya and Hindi, and Oriya makes for a sizeable section. While this may make it difficult to market in the country (as bilingual films rarely, if ever, sell) it lends great authenticity to the film. This worked out especially well because the actors playing Naxalites and the CRPF, both of whom are usually the outsiders in such lands, were from Mumbai. Those playing the adivasis were from Orissa. And, in Makhija’s words, Nandita Das, “who speaks both languages, really bridged this gap”, as Hemla was meant to.

The significance of language in resolving what had been called “India’s greatest security threat” has been brought into full play through Taram Taram, which is inspired from a Telugu adivasi song that teaches children the ways of adivasi life. Hindi film lyricist Rajshekhar has written the songs using a mix of Hindi, Oriya and Telugu, with a smattering of Bengali and adivasi words.

“The primary source of conflict is miscommunication,” says Makhija. “Nobody wants to ‘listen’ to the other. The government / industry does not want to listen to the adivasi’s problems. The Naxalites, grown exceedingly mistrusting, do not, after a point, want to have dialogue.” And so, Manoranjan, the CRPF commander who calls the shots in the film (Alyy Khan), is partially deaf from a landmine blast. His suspects have to scream for him to be able to hear them during an interrogation, and even then barely so.

Oonga is not without the flaws a first film is often prone to. The background score is heavy-handed and overbearing in parts. In snatches, particularly in scenes set in the Maoist camp, the dialogue and performances are ridden with cliché. A climactic sequence has the imaginary emergence of ten heads on a character to reiterate the metaphor—Oh, look here is Ravana!—needlessly. There is a character of an adivasi seer of sorts, who predicts things and advises people, which—while such characters may well exist—does not add much to the narrative. And, really, there can be better depictions of urban greed than a fat old lady eating chaat in fast-mo.

Yet, despite these niggles, what endears you to Oonga is that it’s made by a filmmaker who, even after endless research and thought, isn’t afraid of admitting he doesn’t really know what to make of the Naxal situation (and who does really?). “Our primary concern in Oonga was to present a scenario where no one, apart from blind capitalistic greed, is really a villain,” says Makhija. “Everyone—from the CRPF troops, to the Naxalites, to the adivasi—are victims of a scenario where ‘development’ has come to mean industrialization at any cost, even that of human lives.” After a slew of films on the issue in the last decade (Red Alert: The War Within, Rakhta Charitra, Chakravyuh… for more read here) it is refreshing to find a director who does not view Indian Maoism as an opportunity for the next wild western or friendship saga.

Take an incident towards the end of the film, where Manoranjan decides that the children of Pottacheru, Hemla’s students, should be rounded up and brought to the CRPF station (incidentally, a school converted into a bunker) for questioning. While in Koraput, Makhija had tried to help Sharanya Nayak to free juvenile adivasis who had been housed in adult jails under the charge of ‘armed public assembly’. Their ‘arms’ had been bows and arrows, which the adivasi youth carry routinely. “The official papers had wrongly shown even a 12 year old to be 18,” says Makhija. “We got registers from the kids’ schools to prove their age. But when we landed up outside the jailor’s office, the man simply walked past us even as we spoke to him. We followed him for hundreds of metres, begging him to at least hear us out, only to have him walk silently in through a door and shut it on our faces.”

“I might be weaving conspiracy theories here, but it seems too convenient to me that such jawans are always posted in states where they don’t speak the local language,” he says. This alienates them from locals and their problems and it’s unlikely they will think twice before carrying out a brutal order. “Which brings me to Avatar,” Makhija says. “Pandora could have been Malkangiri or Koraput in Orissa. Earth could have been Rajasthan.” And Oonga could have been the Na’vi, or, closer home, Ram. But thankfully he is not. Instead, as the film progresses, he transforms into an idea of both, come despairingly alive: an angry eight year old boy, blue paint smeared all over himself, with a bow and arrow in his hands— not in the middle of a theme park or a Ram Leela maidan, but a battlefield.

Planet of the Natives

ArticleOctober 2013

By Rishi Majumder

By Rishi Majumder

Rishi Majumder is Senior Editor, TBIP.