-

DVD case cover of Small Wonder

DVD case cover of Small Wonder -

Poster for Small Wonder

Poster for Small Wonder -

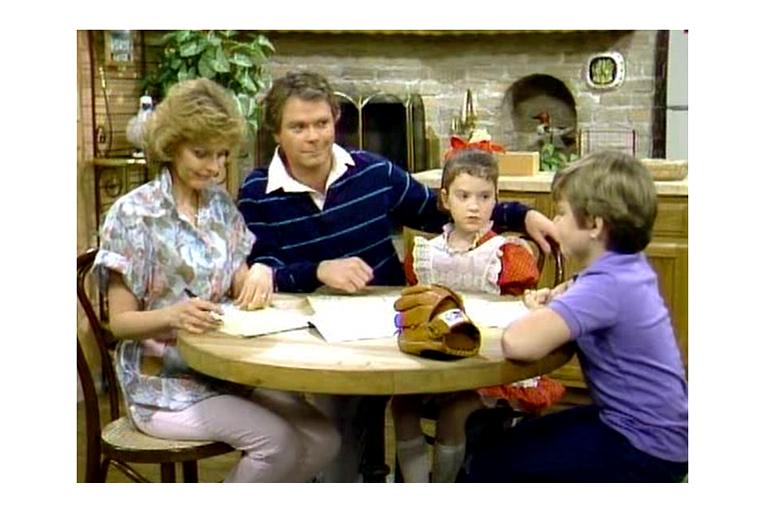

A screenshot from Small Wonder

A screenshot from Small Wonder -

A still from Friends

A still from Friends -

A Span cover

A Span cover -

A Soviet Life cover

A Soviet Life cover -

A still from Mahanagar

A still from Mahanagar -

A still from Mahanagar

A still from Mahanagar

Nakul Krishna on the American Dream, Indian values, a touch of lipstick and what we and our movies have made of such ideas.

When I was eight years old, I came home from school every day to an American sitcom called Small Wonder. I have never yet met an American my age who has seen it; I have never yet met a middle-class Indian my age who hasn’t. If you belong to that second category, you’ll probably know what I mean. I for one saw every episode twice, first in English, and later dubbed in Hindi. You probably did too. You might remember its opening music— “She’s a small wonder / Lovely and bright with soft curls… ”

Small Wonder is set in an unnamed American town, in the suburban home of the Lawson family. Ted Lawson is an engineer at United Robotronics, married to Joan, who is, when the show starts, a housewife. In the first episode, he brings home a robot he calls V.I.C.I. It stands for Voice Input Child Identicant, but they call her Vicki, and pass her off, for reasons too complicated to explain, as a member of their family.

Over the show’s four seasons, she is legally adopted after the social services get suspicious, and even gets to go to school. Even for a work of ‘soft’ science fiction (in other words, one with little interest in making the science believable), Small Wonder is full of implausibilities. How does no one notice that Vicki, who speaks in a robotic monotone throughout, is, well, a little strange?

For this but not only this reason, there are television critics who’ve declared it to be the worst ever show on American television. This can’t be strictly true: where American television is concerned, there are always lower depths to plumb. But even if it is, it doesn’t matter. Small Wonder got to me long before my inner critic could think about whether it was any good. And it is perhaps the mark of something in the show, an earnestness, a kind of naïve integrity, that its absurd premise soon comes to seem the most natural thing in the world.

I love bringing up Small Wonder in conversation with Indians of my age and background. It is, along with the opening music of Doordarshan News and that image of Sushmita Sen as Miss Universe with her hands to her mouth, part of that set of collective memories that make for the materials of future nostalgia. But it interests me in a different capacity as well.

I am interested—it is one of the subjects of my academic work—in what goes into the making of our sensibilities. The little things—an image, a story, a turn of phrase—are often the most important. They come to us before we are able to subject them to rational scrutiny. They go into how we perceive the world, into recesses of the mind so deep that it is an impossible task dislodging them afterwards. There are places no argument can reach.

Small Wonder was my first glimpse of (what I did not then know was called) the American Dream. If there is a part of me that still believes in that dream, it is the one schooled on the images of suburban happiness I first encountered in the house of the Lawsons.

The Lawson house is a stereotypical ‘sitcom’ house, full of stereotypical sitcom furniture. But it presented my eight-year-old self with the image of a nuclear family in a home of their own. The children, if not so much dad, helped with the chores and things were discussed at the dinner table. It was an image of family, the American family, not the province of indiscipline and disrespect I had been told it was—an old Indian cliché—but a quite familiar mix of humour and tough love, full of soppiness and teachable moments.

Small Wonder was also a glimpse—though it is not the most obvious way of looking at it—of American capitalism. Ted Lawson, let us remember, works at United Robotronics, and we are on half a dozen or so occasions given episodes whose plotlines centre around its internal shenanigans. A memorable episode has the president of the company, Mr. Jennings, telling (evidently for the umpteenth time) his rags-to-riches story about building his company from nothing. For reasons again too complicated to explain here, Vicki has been pumping laughing gas into the room while this happens. Soon the point of the story is revealed: Mr. Jennings is about to announce the necessity of laying off workers to save the company. His sombre announcement is greeted with bellows of uncontrollable laughter— the writers and actors handle the irony nicely: all is not well in Reagan’s America.

Yet, American capitalism could have no better advertisement. This image of white-collar workers living their idyllic family lives supported by a regime of science and technological innovation is a compelling one, even if there is the further question of whether this was an accurate representation of American capitalism. But I wonder about what these images did to those of my generation watching them as the world was learning how to conduct itself now that the Cold War was over.

There is one episode in which the Cold War figures explicitly. A young schoolboy from the Soviet Union is touring the United States, taking on and intending to defeat American students in a series of one-on-one quizzes— proof, surely, of the superiority of the Soviet educational, and no doubt political, system. Young Vladimir seems a formidable opponent, until it is discovered, halfway through the episode, that he is, in fact, a robot.

The Lawsons, who had baulked at having Vicki compete against a real boy, even a Soviet one, now need have no such qualms. Vicki gets to compete against him, and things are neck and neck, until Ted decides that things have gone too far and gives Vladimir a bit of ‘old-fashioned American reprogramming’; the echo with ‘re-education’ was no doubt deliberate. Vladimir interrupts the quiz to announce that he is defecting and that he loves America, and breaks out into a robotic rendition of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’. Small Wonder is the sort of programme that could well have been made by the cultural wing of the CIA. It probably wasn’t, but the CIA couldn’t have produced a better piece of propaganda if they’d tried.

It is central to my experience of Small Wonder that what it depicted, its science fictional component apart, I took to be a portrayal of what American life was like. Other things people of my generation watched—the Wonder Years will certainly ring some bells and, five or six years later, Friends—were presenting us with appropriately smoothened, comically inflected pictures of somebody else’s way of life, lives people somewhere far away were leading. And the crucial thing is that these were not, as generations of Indians before mine had thought, lives fundamentally without values except those of materialism and technological efficiency, but values of a more straightforwardly moral kind: liberty, individualism, and the pursuit of happiness.

Neither America, nor the West more generally, nor capitalism, come out well in the Indian cinema on which my parents’ generation grew up— I’m thinking of the long lineage of films from Purab aur Pachhim (1970) through Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), and their descendants: Pardes (1997), Aa Ab Laut Chalen (1999), Dhan Dhana Dhan Goal (2007), Namastey London (2007) to Luv Shuv Tey Chicken Khurana (2012). With their images of Indians abroad either full of nostalgia for the old country, or full of contempt for it until they have a sudden epiphany. Then the boys cut their hair, girls cover their legs, everyone gives up smoking, and all is well with the world again.

It is a common trope in this genre of cinema that the West—that undifferentiated continent—is a place without values. Only the lure of money makes it worth an Indian’s while to be there, such is its unmitigated racism, greed and licentiousness. The old here are refuse, to be emptied into old-age homes, and women, who spend their days smoking in louche nightclubs, are mere objects. And so on— the images are too familiar to need rehearsing. The point is that only India, the old country, has values.

Against this, there were the images on television where the West spoke for itself every day. The images on television were ones of autonomy: the suburban nuclear family not as a cruel rupture from some purer and more organic way of life but an ideal in its own right. And they were images of freedom: living alone in a big city not as a tragedy to be avoided with an early marriage but as an adventure, at least while it lasted. The relationship of children with their families, especially their parents, was presented with a mixture of irony, awkwardness, indulgence and love, a good distance away from the solemn and sentimentalized images of these relationships our cinema had given us. It is, again, a further question whether these were ‘better’ values than the ones our cinema had been defending. Still, it was a help to be shown that these things were values, even if they were not our own.

I mentioned CIA propaganda, in part because such a thing did exist— the Cold War was, as we now know, in part a struggle for the proverbial ‘hearts and minds’ of the non-aligned. I have the vaguest memory of issues of Span—an American attempt to disseminate images of American superiority across the third world along the lines of the Russians’ Soviet Life—on an uncle’s coffee table. But really, it was the Soviets who had, from the fifties through the eighties, invested in the hearts and minds of India’s young. Pankaj Mishra has an affecting memoir of these years in an essay published in the magazine n+1 some years ago:

Mobile bookshops toured the towns offering subscriptions to Soviet magazines and organising book fairs where you could buy two hardback editions of Russian classics for five rupees (at a time when one dollar equalled 18 rupees). … The mobile bookshops came to our town without warning, often appearing in a field where gypsies from Rajasthan set up their black tents. Inside the long truck, books stood in open dusty shelves, monitored by thin young men in glasses. There were many Soviet translations of Russian classics, in addition to the works of Marx, Lenin and Plekhanov. … My earliest purchases were collections of Russian fairy tales, and I now wish I still had, or could recall the titles of, the beautifully illustrated volumes that enlivened much of my childhood.

There is much in Mishra’s memoir that I can recognize, just about, but mine is the last generation to have any memory at all of the sort of thing he is talking about. Cousins born a few years after me know little of the mixed economy and even less of the non-aligned movement. They did not grow up, as I did, however briefly, on Soviet-subsidized books of lavishly illustrated Russian folktales, and the drawing-room politics of the nineties were not disposed to the same reflexive anti-Americanism of previous decades. Instead, in those drawing rooms sat colour televisions, with cable, broadcasting American propaganda that did its job precisely because it was not made to be propaganda.

In the early 1990s, few people had any coherent idea of the kind of brave new world into which Manmohan Singh’s economic policy was dragging us. Still less did we know what kind of society it would create. Our popular culture has responded in its way to the transition, with both television and cinema in the nineties full of scenes of sinister tycoons signing ten-crore-rupee contracts. But I am thinking about the daily life of capitalism, its effects, good and ill, on ordinary human beings: what does it do to family, what does it do to friendship, what does it feel like to live under it? Here, our popular culture has been of less help.

Twenty years later, we are getting the hang of freedom, that ambiguous value— or rather, the peculiar variety of freedom the American Dream represents. It is a powerful idea, powerful enough to command the loyalty of serious and intelligent people. But I am hardly the first person to point out that the dream always had its dark side— violence and exploitation on the one hand, alienation and loneliness on the other. Yet, the idea can have a hold on some of us.

We should be honest enough not to deny the part of us that believes, sometimes despite itself, in that dream, even if we believe this only because the fairy tales we grow up with were not Russian but American. The immigrant’s New York is going to look nothing like Friends, but the fantasy of New York is part of what brings some of its immigrants there. The half-truth that dares not speak its name in our cinema is the possibility that it is not just the desire for money that attracts Indians to the West— it is also the promise of freedom and the responsibility that comes with it, however seldom that promise is realized.

It is tempting, too tempting, to think the impulse a Western one. But India has always had the ingredients of that impulse– the renunciant in the Sanskrit tradition seeks freedom of a sort, as does the ancient Tamil poet who complains that “living / among relations / binds the feet”. Within the terms of such a worldview, the American dream is a paradox: the householder whose feet are still unbound.

There is a winsome moment in Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963) where Madhabi Mukherjee’s Arati, a housewife unexpectedly successful in her job as door-to-door saleswoman, is offered a lesson in applying lipstick by her (inevitably) Anglo-Indian colleague Edith. Arati protests at first, then blushes, then checks that the door is locked, insists that Edith put “not much, just a little”. Edith reminds her of the “Indian book on sex, you know, the famous one, that said that Indian girls used to paint their lips and eyebrows and fingernails and everything, in the old days. So why shouldn’t you?” Arati looks at herself in the mirror shyly, preens for a moment, then wipes it all off.

Things come to grief for both Edith and Arati soon enough, but the moment stays with you, a brief moment of daring, a little experiment in being free. Not much, just a little.

Lovely and Bright with Soft Curls

ArticleDecember 2013

By Nakul Krishna

By Nakul Krishna

Nakul Krishna has lived since 2007 in Oxford, England, where he studied Philosophy and Politics and now teaches the works of Plato and Aristotle to students at the University of Oxford. He is writing a doctoral thesis on the idea of ‘common sense’ in the history of Western philosophy from Socrates to the present. His writings on history, literature, politics and culture have been published in the The Caravan, The Hindu, New Statesman, The Indian Express and Livemint.