-

Shenky at the weekly Daryaganj Book Bazaar, waiting for his elusive 'VIP' customer

Shenky at the weekly Daryaganj Book Bazaar, waiting for his elusive 'VIP' customer -

He sells hand painted posters for Rs. 200 to Rs. 300. Here he is showing off a poster of Manoj Kumar's Shor to a potential customer

He sells hand painted posters for Rs. 200 to Rs. 300. Here he is showing off a poster of Manoj Kumar's Shor to a potential customer -

Carrying his posters back home in the backlanes of Daryaganj

Carrying his posters back home in the backlanes of Daryaganj -

Sifting through his 3000 odd posters in his house. The posters are a legacy left to him by his father

Sifting through his 3000 odd posters in his house. The posters are a legacy left to him by his father -

Too precious to sell : A rare Maratha Mandir Mughal-e-Azam ticket which he doesn't want to part with

Too precious to sell : A rare Maratha Mandir Mughal-e-Azam ticket which he doesn't want to part with -

Shenky hopes to move up the social ladder through his hand painted poster business

Shenky hopes to move up the social ladder through his hand painted poster business -

Sharing a light moment outside Delite cinema hall, where he watches a film every week

Sharing a light moment outside Delite cinema hall, where he watches a film every week -

He wants to move out of Daryaganj and set up shop in New Delhi

He wants to move out of Daryaganj and set up shop in New Delhi

Shenky, a film poster seller in Daryaganj, sees the film memorabilia collection his father left him as an inheritance that is his ticket to a better station.

“Rakh de rakh de wahin pe bhai, tere kaam ka nahin hai. Aage jaa.”

At the Sunday Book Bazaar in Old Delhi’s Daryaganj, where everyone is desperate to sell, Mohammad Suleiman dismisses a prospective customer who has stopped at his Hindi film poster collection. “It’s not for you, move on,” he says to the young man leafing through a booklet of songs from the 1982 Dharmendra starrer Teesri Ankh. It has been an uneventful day so far for Suleiman. He has not sold anything.

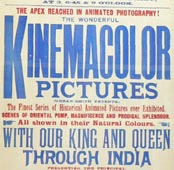

Opposite a board announcing the availability of ‘Sabse Sasti Magazines’, next to a heap of ten rupee second hand books, Suleiman has set up shop on the pavement, like everyone else in this bazaar. He sits on a stool, surrounded by film booklets and A2 size posters. “This is made by hand,” remarks a passerby, referring to a poster of Boot Polish at the centre of it all.

Suleiman, who sells posters, song booklets and film memorabilia, is looking for a particular kind of customer. “My customer is royal,” he says. “He is a VIP. He is one who is a lover of the old and the antique.”

This rules out most of those who pause before his collection at the bazaar— students interested in cheap school textbooks or simply those out for a Sunday stroll. Suleiman’s visiting card calls him a ‘Cinema Poster Historian’. Also, ‘Shenky’, a name he has adopted because his own is “too heavy” for New Delhi’s “high society”, a society Shenky aspires to sell to.

It was, in fact, on a visit to a regular haunt of this society two years ago—an expensive poster store in Hauz Khas Village—that Shenky, now in his forties, discovered he had had “a treasure” back home all along.

***

Shenky’s family hails from Nainital originally, but his father, Ali Hassan, was born and brought up in the nearby locality of Chandni Chowk. He was a factory supervisor. In the picture Shenky paints of him Hassan appears to have had three interests above all else: his work, smoking beedis and Hindi films.

Almost every day, after work ended at 5 pm, Hassan and his friends would be at one of the single screen theatres in the Old Delhi area. “Such as Excelsior, Jagat, Novelty or Jubilee. Raj Kapoor and Rajesh Khanna were his favourite actors,” Shenky says. Cinema halls used to be different back then. Says Shenky, “There was no other entertainment at that time. We did not have the hausla to go anywhere else.” Hausla, or courage, which was needed even for leisure in a society that remained feudal in its outlook. Connaught Place, nearby, was “hi-fi” in Shenky’s words. He recalls the apprehension they felt in visiting such localities where one would have to be mindful of what one wore. The single screen cinemas of Old Delhi provided for a kind of parallel space, a shield of sorts from the harsh class divisions in society.

Hassan was also a collector of film memorabilia. By virtue of his close association with cinema hall owners, many of whom he did odd jobs for, and because of his friends being on the staff of these theatres, he was able to eventually build a collection of 3,000 posters. “He would not show the collection to anyone.” Not even to Shenky, even though he was the only one from the family Hassan took along to watch films. “He would collect whatever he could lay his hands on.” Those days song booklets would be sold during the intermission, as part of the heavy print publicity distributors relied on. So these too found their way to Hassan’s home. Shenky has added steadily to this personal collection, which he sees as a legacy of his father’s Hindi film “deewaanaapan”, by frequenting kabadiwalas and cinema halls to look for more collectibles.

But till that fateful visit to Hauz Khas Village Shenky had never thought of these as having business potential. Perhaps because they didn’t, for a long time. Ranjani Mazumdar, in an essay on the Bombay film poster, writes that in a “strange twist”, the “once ordinary” hand painted poster acquired the status of an “art object” as it disappeared from streets and public places. Once, it had been “seen plastered on walls in various parts of the country and available for a price of five rupees in the streets till the early 1990s”. With its disappearance, it has “acquired the status of an ‘art’ form as collectors enter the field of preservation, display and sale of the traditional poster”.

What Shenky saw that day was the possibility of bridging the class divide he found himself on the wrong side of. “I initially sold to the Hauz Khas Village poster shop. But they were paying me too little, so I decided to start on my own.” He used to work at a shoe shop in Old Delhi. Now he could hope to work for himself. Shenky recognized, however, that this transition would rely on people of means willing to invest in his collection. To begin, he rented a flat in Daryaganj.

Two years later Shenky is at the weekly Sunday Bazaar, still trying to make that transition. “All this came to me because of my father, otherwise I would have been working at the mercy of someone else.” What started for his father as a hobby has become for Shenky an inheritance, the capital on which he hopes to build his future.

***

Among those selling at the bazaar, Shenky is the object of quiet envy. Even though most people walk by his collection, everyone is convinced he is making a lot of money. Rehan, who sells stationery next to him, is hesitant in disclosing his surname. He was intrigued when he first saw Shenky set up shop. “Initially, Shenky would distribute his visiting cards to whoever cared to give his collection a look and we would wonder why he is doing this,” Rehan says. Shenky knows he can’t take every old poster to the market so he puts on display a few samples from his collection and distributes his contact information to whoever expresses interest, hoping they are back sometime. If they are, he leads them to his flat, behind the market, where the posters are stored.

“Then we got to know he is famous,” Rehan continues. “He has been written about in the papers. There’s a lot of money in this. He doesn’t have to rely on everyday customers. People must be approaching him directly.” Shenky sells each poster for between Rs. 300 and Rs. 400. The song booklets are for Rs. 100. He says this is cheaper than what most people offer, that the karigiri (workmanship) of the posters makes them worth it. “Painting involved hard work and love,” says Shenky as he points to a poster of Night Club from 1958. He says he earns between “Rs. 6,000 to Rs. 7,000 per month”. Sometimes, for weeks, there is no buyer. Then, suddenly, there are orders for many posters. He has also begun to sell small antique items. He claims to be doing sufficiently well for his family of four— himself, his wife and two sons. His daughter is married.

On some days customers have specific requests, such as one who had insisted on a Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro poster. “These days people have also started gifting posters as wedding presents. DDLJ is very popular.”

In her essay, Mazumdar also speaks of the “power of nostalgia within modernity”, fuelled by the release of old films on television.

Advocate Sanjay Hegde, one of Shenky’s clients, has the poster of Zamaanat, an unreleased Amitabh Bachchan film, framed and displayed in his office chamber. “I have not collected with the intensity of a ‘collector’,” says Hegde. “But sometimes you want a film poster because of a certain memory associated with it.”

Today, a man and woman stumble upon Shenky and his posters while looking for books. The two posters they ask for—of the films Mughal-e-Azam and Kaagaz Ke Phool—are among the 12 he has chosen to bring to the market. “These are for my mother,” the woman says. “We think she’ll like them.”

Regular customers drop by as well. Syamantak, a designer, has bought three posters from Shenky. “I’m a regular at this market. One day I saw these posters,” he says. “I bought Shree 420, Shatranj Ke Khilari and Anand.” A NIFT student, he is interested more in the posters themselves, because they are “hand painted and old”, than in the cinema they advertise. Syamantak is unconcerned about where the posters come from. He says he couldn’t care lesser if “Shenky paints them himself”.

Accompanying him is his friend Aman Nigam, a software developer, who chances upon a song booklet of the 1990 Tamil film Anjali. “I have seen this film on television when I was a kid,” he says, humming a song from the movie.

There are also customers whose choices Shenky doesn’t understand. Leena, a Ukranian living in India, visits his stall every Sunday. She seems to be looking for something specific today but isn’t able to explain what it is to Shenky. She can’t speak English, only broken Hindi. She sifts patiently through two piles of movie song booklets, leaving out classics and picking out ones from more recent films. She doesn’t like the painted posters and prefers movie stills instead. Shenky shows her one of Amitabh Bachchan in Deewaar but she waves it aside. “A collector would pay so much for this,” he says. She ends up buying 10 song booklets of films she hasn’t seen.

***

“I am thinking of setting up shop in South Delhi,” Shenky announces suddenly. “Kaisa rahega?” Today “hi-fi” areas like Connaught Place aren’t half as intimidating to him as he said it was for his father.

Nevertheless, he will head to an Old Delhi favourite, Delite Cinema in Daryaganj, later this week, to catch one of the latest Hindi releases. He likes Delite, he says, because it caters to “both the old and new”, by which Shenky means audiences from Old and New Delhi.

Film scholars wonder whether technology will enable a reproduction of these posters from the yesteryears in greater numbers, as well as a more democratic distribution, freeing old movie posters from the clutches of collectors and galleries. But Shenky, who has built his dreams around the novelty of the vintage Indian film poster, would not like this to happen. At least, not till he has discharged his father’s collection of 3000. So far, he has only sold “about 300”.

On the Back of a Movie Poster

Article, Photo FeatureMay 2014

By Aakshi Magazine

By Aakshi Magazine

Aakshi Magazine is a freelance writer and film critic based in Delhi.

By Garima Jain

By Garima Jain

Garima Jain is a filmmaker and photographer. She worked with Tehelka magazine as a photojournalist where she photographed and wrote on emerging Indian culture. Her documentary film Running On Empty, is based on the life of a London taxi driver.