-

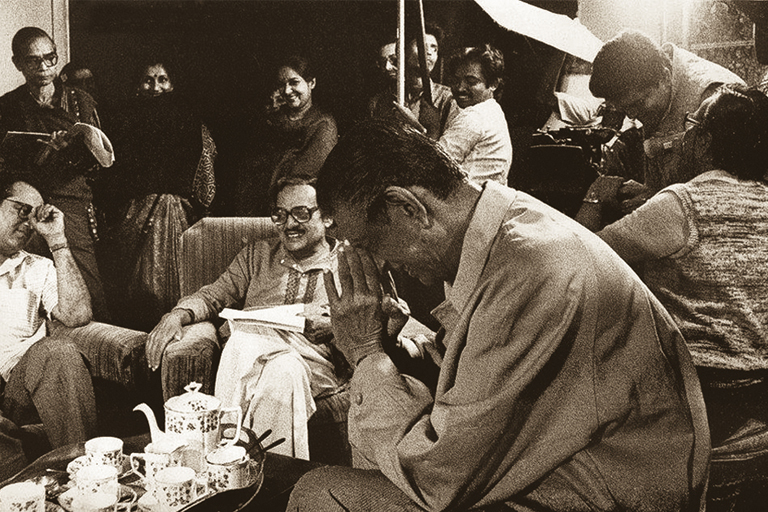

Utpal Dutt and Satyajit Ray on the sets of Agantuk | Courtesy S.M.M. Ausaja - Private Collection

Utpal Dutt and Satyajit Ray on the sets of Agantuk | Courtesy S.M.M. Ausaja - Private Collection

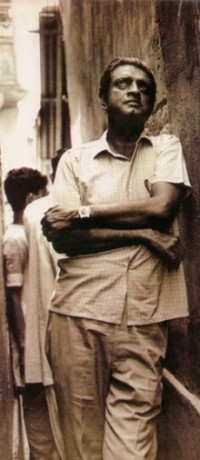

Satyajit Ray | Courtesy S.M.M. Ausaja, Private Collection

Every once in a while we like to flip a few pages and go back to a place in history which gives us a unique vantage point to reevaluate our shared perspective of us and our movies. Here is one such page from modern history.

Utpal Dutt, actor-director-playwright, was as committed to fusing his art with his politics as he was to his enviable zest for life. This is the text of a fiery address he delivered in a seminar on Satyajit Ray organised by Sahitya Akademi, Sangeet Natak Akademi and Lalit Kala Akademi in Delhi on May 15, 1992, three weeks after Ray passed away at the age of 70. The Ram Janmabhoomi movement to build a temple to Lord Rama in Ayodhya, to which he refers in the first paragraph, culminated seven months later, on the 6th of December 1992, with the destruction of the medieval Babri mosque by mobs backed by right-wing political parties. On August 19, 1993, Utpal Dutt passed away, aged 64.

RAY, RENAISSANCE MAN?

The latest labels they have found for Satyajit Ray are the Bharat Ratna and Renaissance Man. The paper distributed for this seminar also describes Ray as a product of the Indian Renaissance. While his body was lying in state in Calcutta, the Doordarshan commentator repeatedly spoke about Ray being a representative of the Indian Renaissance. What, pray, is the Indian Renaissance? History is quite silent about it. We once heard historians talk of the Bengal Renaissance, but an Indian Renaissance is a recent invention of the government in New Delhi. When did this mythical Indian Renaissance begin? And when did it end? Or perhaps it is continuing at this moment, secretly, within the movement for smashing the Babri Masjid and building a Ram temple in its place? Perhaps the Indian Renaissance is to be discovered in the recent widow-burning in Rajasthan or in the great Indian sport of burning brides for dowry? Or perhaps the mass poverty and illiteracy of India are the hallmarks of the great Indian Renaissance? Claiming Ray’s genius for something that is essentially Indian is a shameless bluff, and merely reminds one of how every Greek city claimed Homer after his death. The Government of India, as usual, woke up later, after a night of revelry, discovered a genius in Calcutta and hastened to confer something called the Bharat Ratna upon him– only because the Americans gave him the Oscar. Of course, Ray had previously won every prize the film world has to offer—at Cannes, at Venice, at Berlin—but they are merely European prizes and don’t count! Oxford University conferred a doctorate on him, but, of course, you have to be somewhat learned to realize its importance. The President of the Republic of France flew to Calcutta to pin the Legion of Honour on Ray’s jacket, but then France has no Seventh Fleet to prowl the Indian Ocean and we are not holding a joint naval exercise with her. But an American award is a different thing altogether. So the game of sharing in Ray’s glory began in great haste in New Delhi, and, since the man was already in a coma, it was safe to heap the Bharat Ratna on him. Men in coma cannot refuse awards.

The invention of this myth of the Indian Renaissance and making Ray its representative is similar to this late attempt to claim a share in all the honours the world has showered on him for so long. It is ironical that USA is the only country that has not yet shown any of Ray’s important films commercially. In fact, the American people remain ignorant of what his films mean. The Oscar comes from a small group of film specialists. The game is clear: we honour you, we worship you, but your creations are not wanted here. Our audiences will be fed on American trash, and trash only; we do not want a trade-rival in this country.

The Indian government’s hypocrisy is equally brazen. It is shameful that, while conferring its highest award on Ray, it has kept Ray’s film on Sikkim under a ban. We know only too well the antics of the corrupt coterie that controls Indian TV; they have suddenly woken up to their bosses’ belated appreciation of the ‘last representative of the Indian Renaissance’, and showed some of his films after his death— but after making arbitrary cuts and censoring bits of dialogue. Their miraculous intervention changed Ray’s Teen Kanya (Three Daughters, 1961) into Two Daughters, one story having been totally left out. They cut line after line of dialogue in Ghare Baire (The Home and the World, 1984), and wanted to stop Sadgati (The Deliverance, 1981) because the word chamar had been used repeatedly in the film. Please note: Sadgati is a film made specifically for the TV, and challenging its dialogue constitutes an attack jointly on Ray and Munshi Premchand, the writer– pretty bold of TV, one would think. No respect for persons.

Thus the Government of India has substantially the same attitude to cinema as the US Academy: personal adulation for the filmmaker but neglect for, even opposition to, his films. Ray’s films—as well as films by various young experimenters in the medium—need protection from the film-mafia of big tycoons who control distribution, production and every other aspect of filmmaking. The Government of India considers the film industry only a source of endless taxation, and believes a golden handshake with the dying Ray will exonerate it of all its sins. The Government of India appears to be a local branch of the IMF (International Monetary Fund) as far as India’s cultural world is concerned. It is at this moment inspired by ideas of a market economy, of free capitalist growth— in other words, surrendering the young filmmaker to the mercy of the big capitalists of cinema. It approves heartily when the young filmmakers are denied channels of release and driven away from the field. Free competition is the watchword, competition between millionaires and paupers. And if the paupers cannot survive— why, they can go and look for jobs elsewhere. This is the substance of an exit policy enforced on the cultural world, the forced exit of every serious filmmaker, thus leaving the field clear for an unending supply of trash. In the arts, trash always sells better than classics; penny dreadfuls always knock Tolstoy out. Herein is the role of the government— if it is interested in educating its people. There can be no free market in the arts. Just as the government cannot resign its responsibility to check and restrict the sale of heroin, similarly it cannot sit back and say: Ray must freely compete with Bombay. If the Government of India were not composed of a bunch of Shylocks, it would have realized that, given the opportunity to watch serious films for some time, people would reject the gruesome, mindless violence of the commercial cinema and demand more and more socially conscious films. It is a fact that Ray’s films were not originally patronized in Calcutta to the extent that could be considered socially significant. But as he began to pour out more and more films, Ray addicts grew fantastically in number, until the release of a new Ray film became a danger signal to commercial cinema in West Bengal. This is a lesson that the Government of India should have learnt: that classics have to have channels of release to the people; it is only then that they become irresistible. Of course, a government which consists of hirelings of money-bags cannot interfere with their free market and set up the new cinema as a rival to rubbish. Rubbish has therefore been ennobled by a new name— ‘mainstream cinema’, thus declaring to the world that the mainstream of Indian art flows in channels of imbecility.

All this began with Pather Panchali, which the highest executive of the Government of India saw in Calcutta and went red in the face. Fuming, he asked Mr Ray whether showing such poverty on celluloid would not bring India to disrepute in the eyes of the world. A typically Indian question: appearance is all the Indian rulers believe in. Mr Ray’s answer put the executive down immediately: if it is not disreputable for you to tolerate such poverty, why should it be disreputable of me to show it? This cry has been repeated again and again: that films should not present the stark reality of Indian life but must whitewash it, pretend—as in the mainstream cinema—that every Indian drives a Mercedes, that a taxi-driver goes home and routinely turns on the air-conditioner before going to bed and that every Indian girl sports an exotic hairdo. Thus alone can Indian honour abroad be enhanced. The cry has been heard from big capitalists as well as from disgruntled, frustrated actresses of Bombay. A prominent Calcutta newspaper while defending City of Joy—an American film being shot in Calcutta—wrote: ‘If Mr Ray can show the abject poverty of Calcutta, why should this foreign director be denied the right?’ It is like saying: why should Bombay films be denied the right to show violence and rape, since Shakespeare shows them freely? All these organs of big capital were spreading a scare about Ray and the new Indian cinema: that these films do not entertain but make you worry about problems— so avoid them at all cost. Go where the beautiful girl gets soaking wet in the rain while she sings a rollicking number and the macho boy singlehandedly knocks 10 toughs out. That is the real India, where there is no inflation, no unemployment, no suffering.

Ray has shown Indian artistes their responsibility to society: that they must be truthful, that it is not only their right but their duty to probe poverty and expose it, lay it bare for all to see and ponder over the inhumanity of it all. To mix Ray up with the maker of City of Joy is a low-down trick. The people’s objection to City of Joy was not because it showed the poverty of Calcutta, but that it was lying. Dominique Lapierre wanted to probe Calcutta’s underworld, without knowing a word of Bengali or Hindi; in the process, he discovered a tiger from the Sunderbans straying into Calcutta, spoke of Calcutta’s overcrowding being caused by refugees from the Himalayas who had fled the Chinese invasion of India in 1962, recorded a flood in Calcutta where all the ground-floors of all the houses—literally, all the houses—had been inundated and corpses floating so thick in places that you could not see the water. The people objected to the portraiture of a so-called mafia in Calcutta borrowed from the exploits of Amjad Khan and Amrish Puri in Hindi films, without any verisimilitude to Indian reality. City of Joy was crass imperialist propaganda calculated to malign India, and hence the peaceful movement in Calcutta against it.

Let us therefore drop the word ‘Indian’ before Renaissance when assessing Ray’s work. There has been no such thing in history. Historians for a time spoke of a Bengal Renaissance beginning with the rise of Henry Louis Vivian Derozio, the teacher, in the 1820s through the work of Rammohun Roy, Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar, Michael Madhusudan Dutt right up to Rabindranath Tagore. But historians have now withdrawn the word Renaissance from this upsurge of progressive ideas and call it simply the Bengal Reform Movement. They now argue, and rightly so, that a Renaissance ‘presupposes the existence of a revolutionary bourgeois class who through the upsurge of Renaissance ideas advance to capture of power and a democratic revolution’. The British imperialists prevented the rise of the Indian bourgeoisie and therefore ‘Renaissance’ is idle talk in India. But perhaps they have reached a governmental decision to use the word ‘Renaissance’ loosely, to describe certain qualities of Ray’s art, irrespective of historical context. History has never been a strong point of the bureaucrats in New Delhi. One remembers with horror the various histories of the Indian freedom movement compiled by them, where India appears to have won freedom because she dutifully wove khadi and drank goat’s milk, where the Naval Mutiny of Bombay does not appear to have happened, where Subhas Chandra Bose and the Indian National Army are given five lines of dubious prose, where Bhagat Singh is actually criticized for being a terrorist.

If the word Renaissance has been loosely attached to Ray, one expects an analysis of his works to trace Renaissance thought in them, what these ideas are and how they have appeared in his films. But alas, for that one requires not only a knowledge of film art but also extensive reading in Renaissance literature, neither of which, one is sorry to note, is available to the numerous secretaries who run the actual work of governing. When Mr Ray was dying, they were busy discovering the identity of the gentleman who used Mr Solanki as a courier to Mr Felber, and even more busy trying to conceal it. Renaissance literature does not fit into this routine. The only explanation of the expression we have heard over the TV is Mr Ray’s amazing versatility. That a man can be a filmmaker, designer, painter, writer of note, music composer, songwriter, book-illustrator and an acknowledged authority on the art and history of printing is inexplicable to them, and therefore they seek to explain it all by a convenient label—as if versatility is the principal characteristic of Renaissance men. But Leonardo da Vinci is not a universal model of Renaissance genius; he was an exception in his time. The other great exponents of Renaissance ideology were men who specialized in just one field, and yet moulded the thoughts of their age. One has never heard of Michelangelo doing anything but paint and sculpt, or Shakespeare doing anything but write plays, or Machiavelli taking time off from political pamphlets to sit down at the harp and compose a sonata. Single-minded devotion to a single art does not negate their claim to being Renaissance men.

The Renaissance released a deluge in Europe which changed social relations, struck a blow at the dictatorship of the Church over man, released the creative energies of men, drove the aristocrats and feudals from positions of social dominance, and generally laid the foundation of a revolution. The ideas that rose from this storm will have to be painstakingly traced and related to their relevance in Ray’s films before such labels can be stuck to him. Time does not permit us to do it on the spot. All we can do is identify certain general trends in Ray’s films and see if they conform to the ideas of the European Renaissance— not Indian, of course, because no such thing exists.

The Renaissance brought man to the centre of attention. Before the Renaissance, man was merely a Christian— oppressed by the Original Sin and a toy in the hands of God. The Renaissance freed man from this intellectual slavery and portrayed him as one who shapes his own destiny by his own will and passion. If there had been anything called an Indian Renaissance, Indians would have been freed by now of belief in kismet, in the pantheon of gods directing man’s destiny and in the burden of a past birth and sins committed therein.

Already in Pather Panchali, Ray’s protagonists suffer not because gods have willed it so but because of poverty created by men. They are evicted from their home by a power that is stronger than gods— a social system that condones exploitation. And this revolt against a concept of gods who crush human beings reaches fruition in Devi, where a girl, a common housewife, is declared a goddess incarnate and is expected to heal and cure every sick villager, until the boy she loves more than her life is dying and is placed before her so that she can touch and heal him. She dare not play with this boy’s life and tries to flee, her sari torn and her mascara running all over her face. One has merely to compare this film with dozens churned out from the cinema-machine of this country, where a dying child, given up for dead by medical science, is placed before the image of a goddess—and, of course, there is a lengthy song glorifying the goddess—be it Santoshi Ma or some such forgotten local deity. Then the stone image is seen to smile, or to drop a flower on the boy’s corpse, and lo and behold, what the best doctors could not do, the piece of stone achieves in a second! The corpse opens its eyes, even sits up. This is followed either by another unending song of thanksgiving, or the boy’s parents weeping and rolling on the ground to show their gratitude. This kind of brazen, shameless superstition is peddled by film after film in this country every year. Are they any less dangerous than drugs? If drugs destroy the bodies of our young men, these films destroy their minds. A proper tribute to Ray would have been to make it impossible to make such filth and, instead, to make arrangements for Devi to be shown all over the country at cheaper rates. Devi is a revolutionary film in the Indian context. It challenges religion as it has been understood in the depths of the Indian countryside for hundreds of years. It is a direct attack on the black magic that is passed off as divinity in this country. Instead of the vulgarized Ramayana and Mahabharata, the Indian TV could have telecast Devi again and again; then perhaps today we would not have to discuss the outrages of the monkey brigade in Ayodhya.

Renaissance ideology was mainly a bourgeois-democratic ideology and therefore had to herald the death of feudalism and the suicidal excesses of the aristocracy. Ray’s Jalsaghar (Music Room, 1958) is a masterpiece in this sense— the lonely, drunken aristocrat, living alone in a massive palace, alienated from life and his fellow men. Doom appears to be written across the tortured face of the landlord, whose pride equals his financial bankruptcy. The history of overturning social relations has been captured in this film with the same unmistakable certitude as in the chronicle plays of Shakespeare. And the social question is emphasized when the little bourgeois visits the lord, a philistine towards art and beauty, but rich and arrogant. He even tries to toss money to the lord’s dancing girl and is prevented by the lord’s stick touching his arm. One can only compare this to the usual portrayal of landlords in Indian commercial films, which not only consistently glorify the lord’s kindness and charity but even where the young hero is shown as a poor boy from the village, you can bet it will be proved at the end that he is actually the lord’s long-lost son. His pedigree has to be established, damn it; a peasant’s son fighting for justice cannot remain a peasant’s son at the end. That would be propaganda for the Mandal Commission.

Shatranj ke Khilari (Chess Players, 1977) does the same thing with Mughal feudals who are so devoid of love of country that they play chess while English imperialists imprison and drag away their master, and their country is enslaved. They could not care less. Where Ray goes way beyond Renaissance ideology is when he chooses to chronicle his own time, such as in Sadgati. We see the heavily lined face of the Indian working man perhaps for the first time in Indian cinema. We have been given glimpses of the Indian proletariat, usually as a slogan-shouting union man in the background, waiting for an Amitabh Bachchan to use his fists to knock the exploiters out. Mainstream films have consistently portrayed the workers as tame middle-class types who wait for a messiah to come and liberate them. Sadgati is the first Indian film to capture the real Indian worker who is doubly exploited: exploited as a worker and exploited as a lower caste. In fact, Sadgati is the prehistory of the present Indian proletarian movement which began in an atmosphere of brahmanical scorn and contumely. The Ray of Sadgati is certainly not a Renaissance thinker but a poet of the contemporary world, confronting the elements of class struggle.

We can extend our study to his last films and see the same political process working in his active, superbly contemporary mind. Ganashatru (An Enemy of the People, 1989), based on Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People, does not end as Ibsen ended his play, with Dr Stockmann standing alone against the world and declaring that the individual is always right and the majority always wrong. Ray knows this is no longer true in today’s world where the masses have advanced to a political role in society. Ganashatru ends with a procession of working men who have arrived to help Stockmann (Dr Ashok Gupta, played by Soumitra Chatterjee in the film) fight his battle. Or take Shakha Proshakha (Branches of the Tree, 1990), where Ray flays the immorality of a middle class that is wedded to the capitalist ideal of making money. Or Agantuk, where Ray indicts so-called civilization which can wipe out a city by pressing a button and at the same time showers contempt and hatred on the tribals of the world who have not learnt the art of murder.

One has a sneaking suspicion that all this talk of Renaissance ideas may well be a ruse to remove from sight the living contemporaneity of Ray’s ideas and relegate him to a museum of ancient statuary which has ceased to bother us now. This suspicion is strengthened when we consider a film like Ray’s Hirak Rajar Deshe (Kingdom of Diamonds, 1980) which was his response to Mrs Gandhi’s Emergency decree. This film in the guise of a fairytale is a blast against all forms of dictatorship which believes in thought-control, prison for the workers, arrests and deportations but which all the while is preparing its own ultimate destruction.

Renaissance is an inadequate term for Ray. He was a moment in the conscience of man.

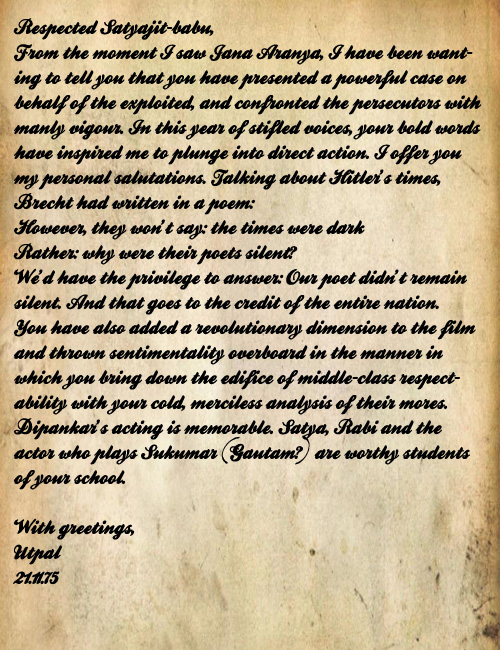

ON JANA ARANYA – A LETTER TO RAY FROM DUTT

Translated from the original Bengali by Samik Bandyopadhyay.

Excerpted from On Cinema by Utpal Dutt, courtesy of Seagull Books. You can purchase the book here

A Moment In The Conscience Of Man

ArticleOctober 2012