-

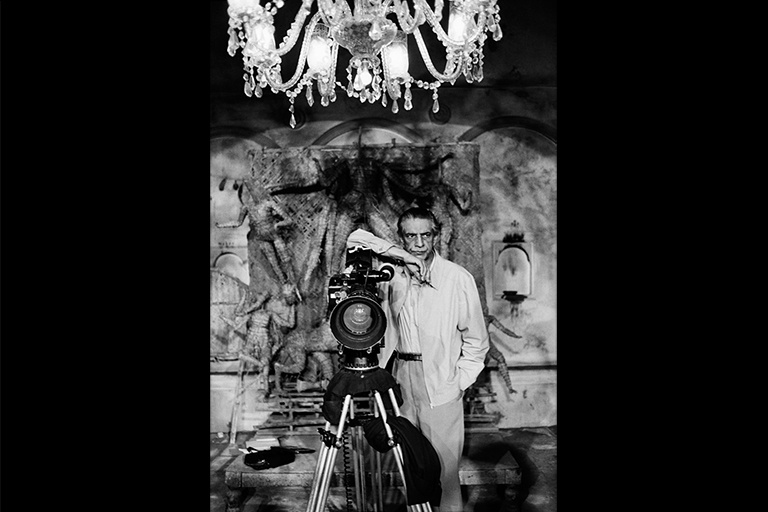

Ghanashatru, 1989

Ghanashatru, 1989 -

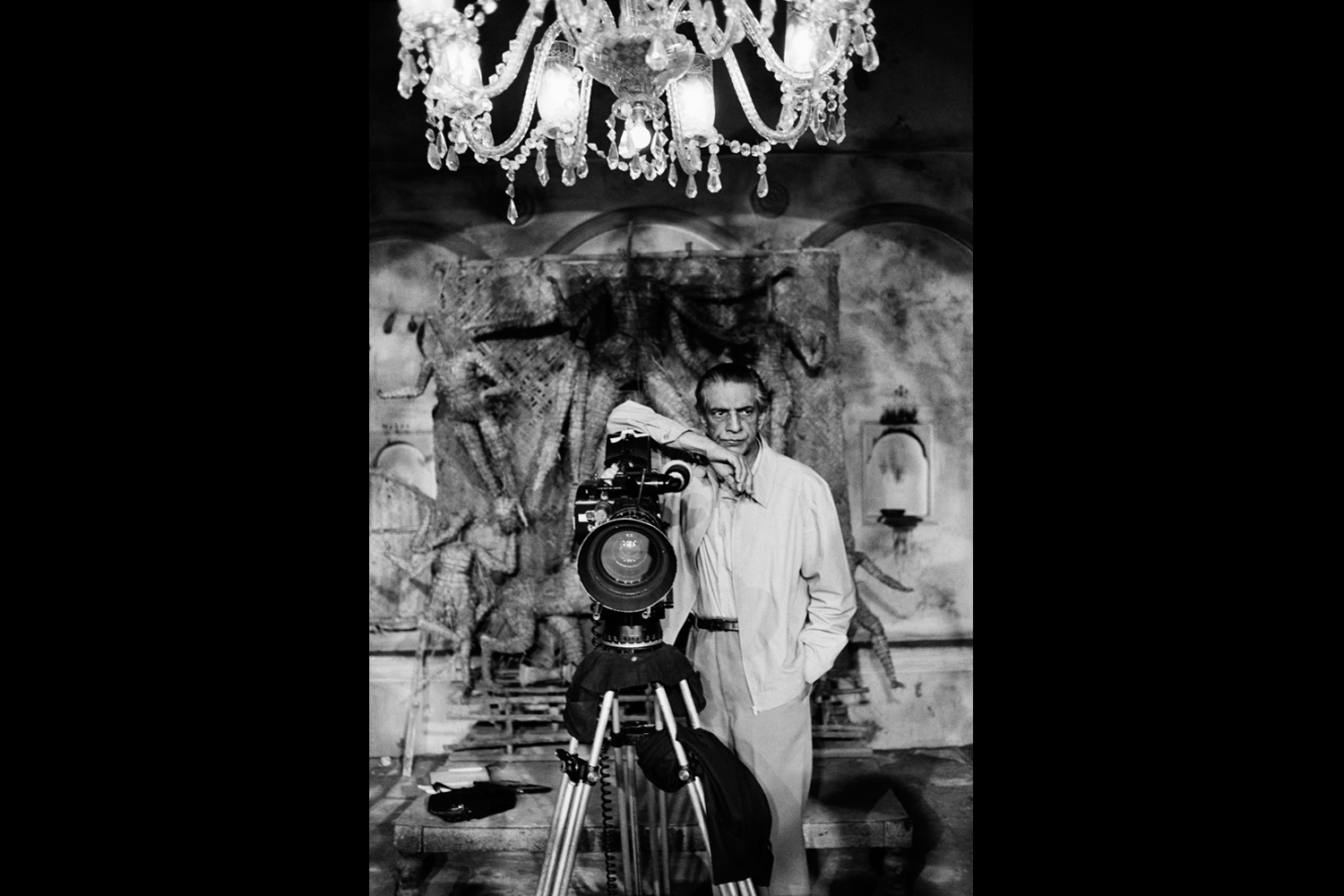

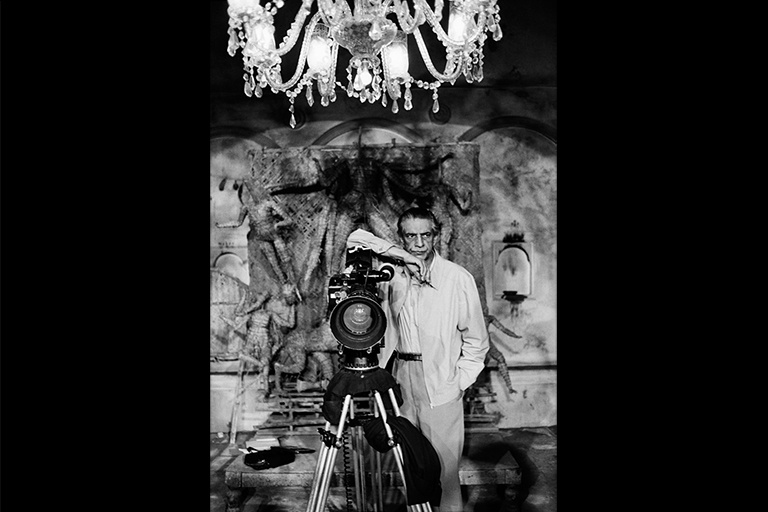

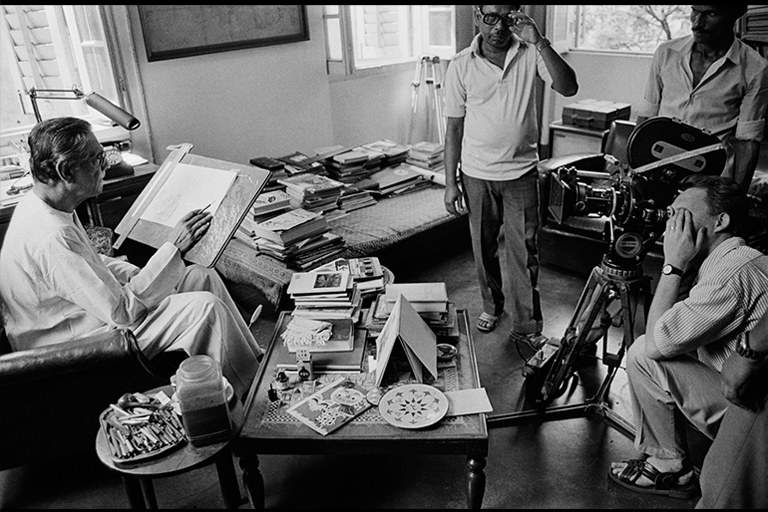

Ray in his study at Bishop Lefroy road, 1988

Ray in his study at Bishop Lefroy road, 1988 -

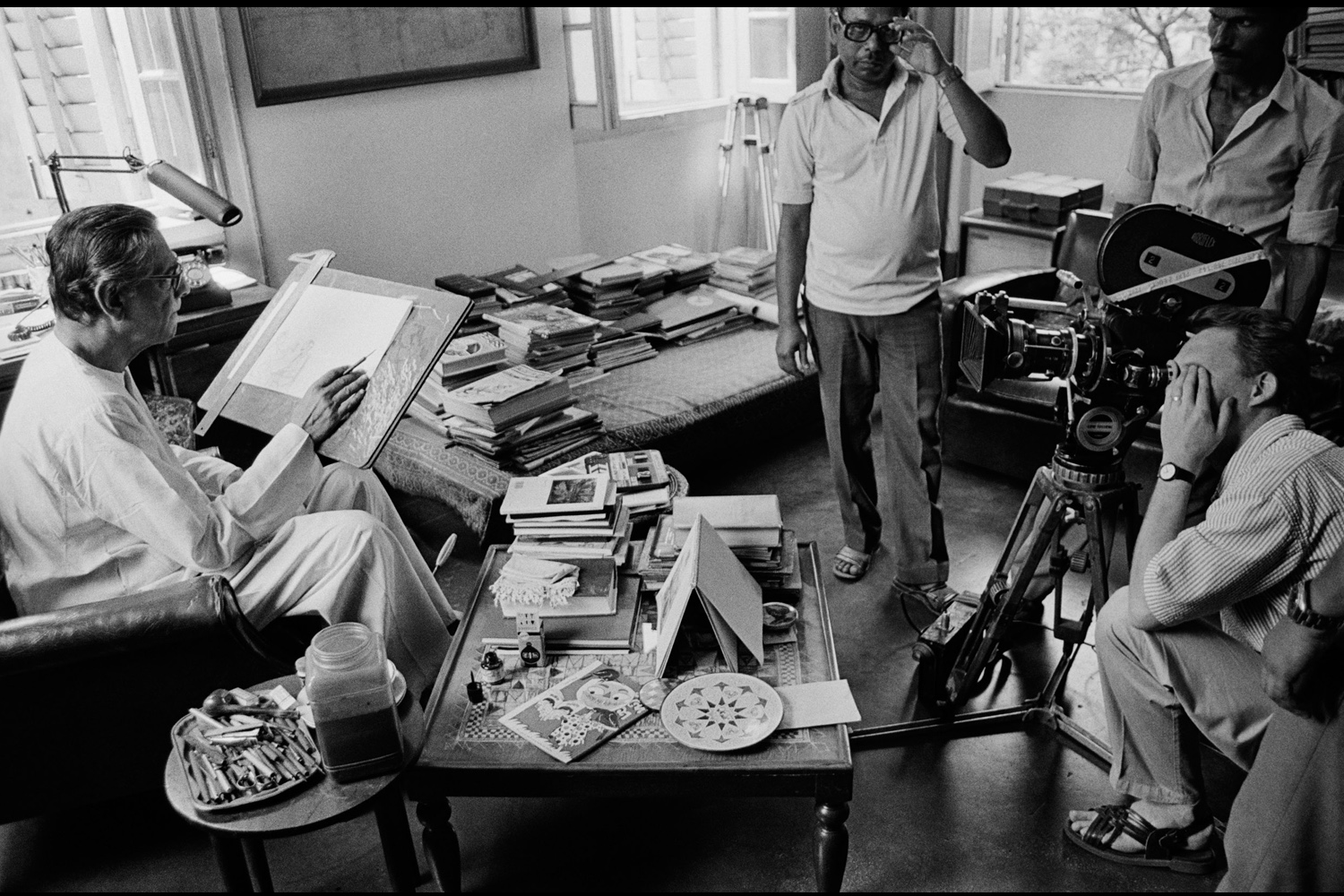

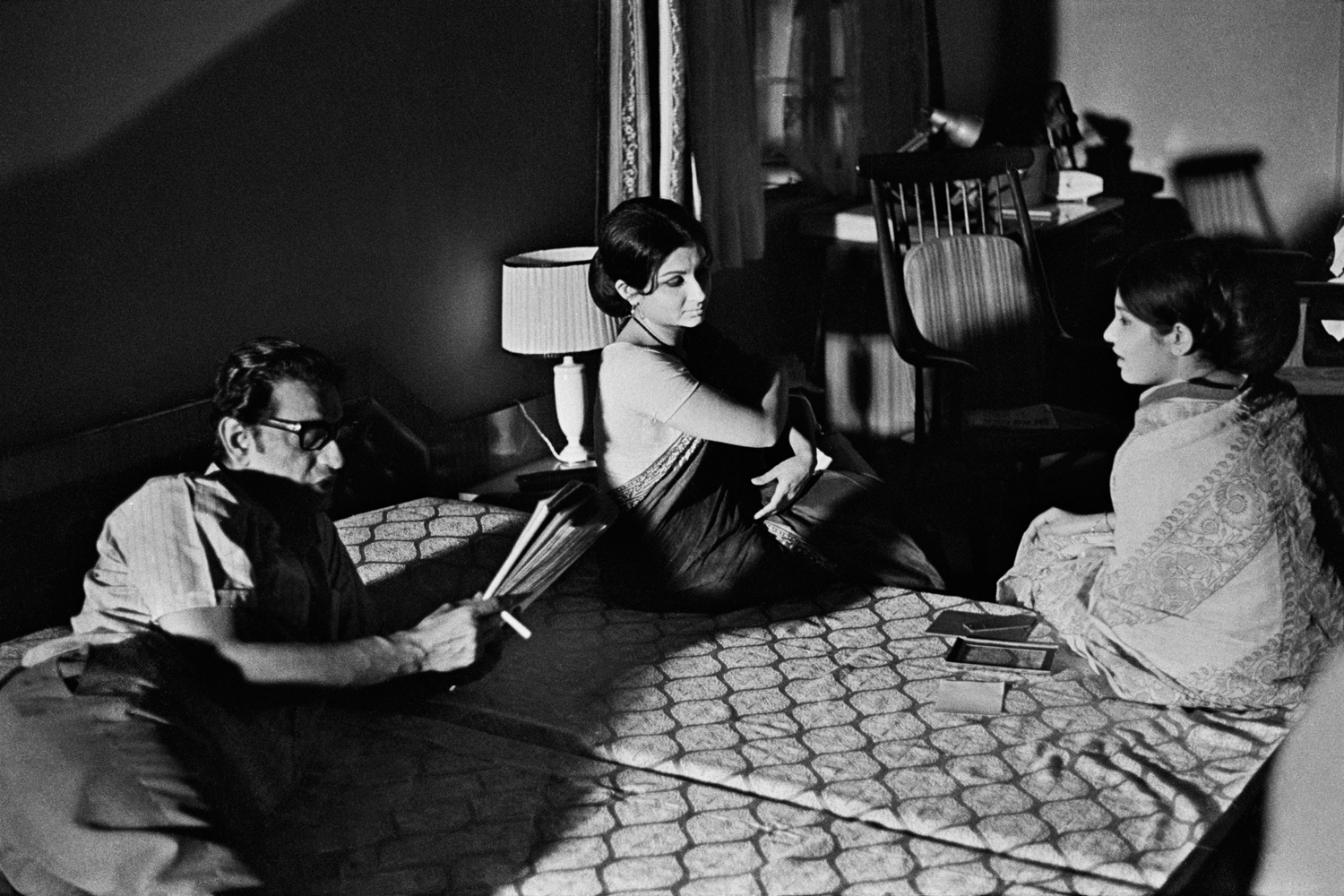

Jana Aranya,1975

Jana Aranya,1975 -

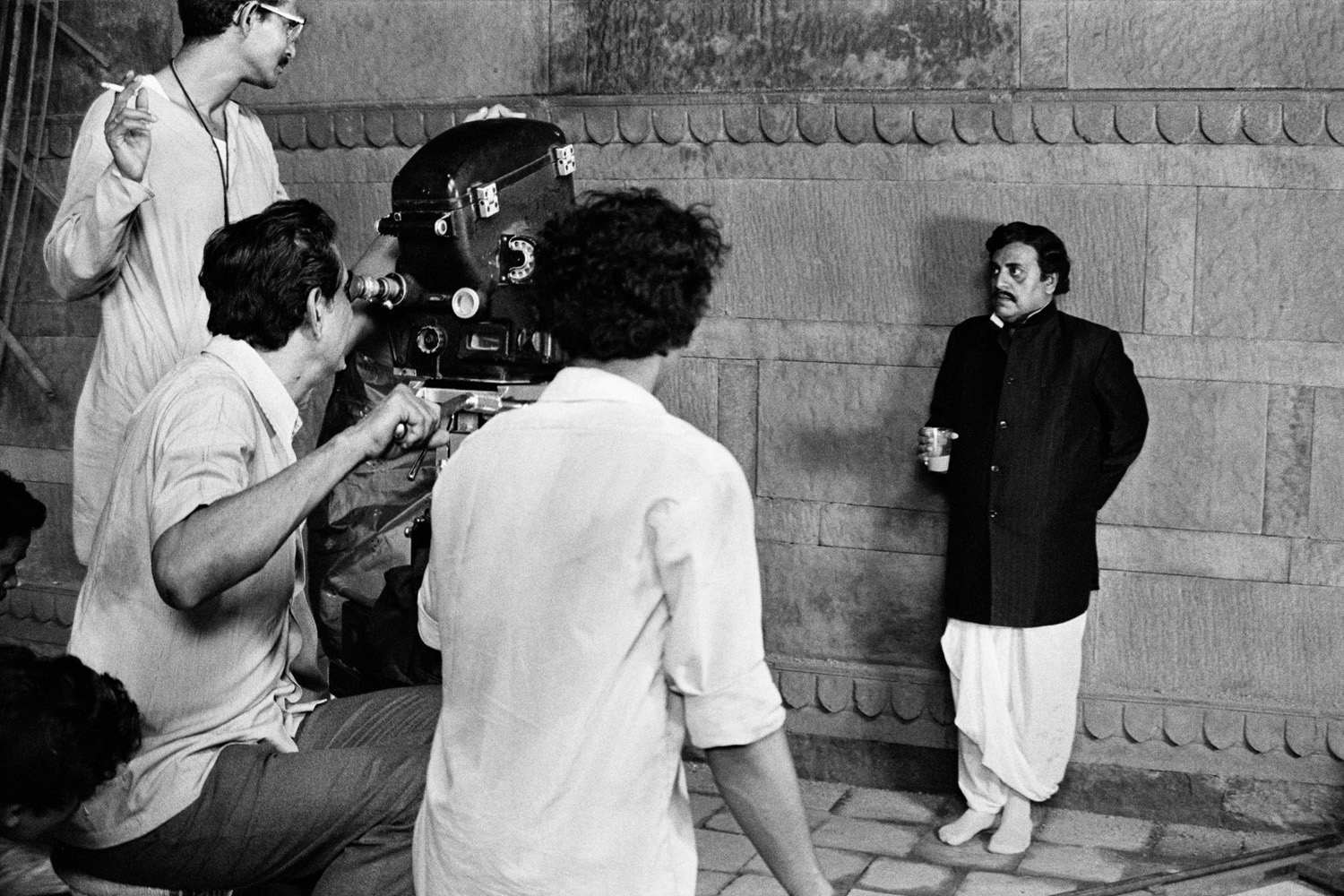

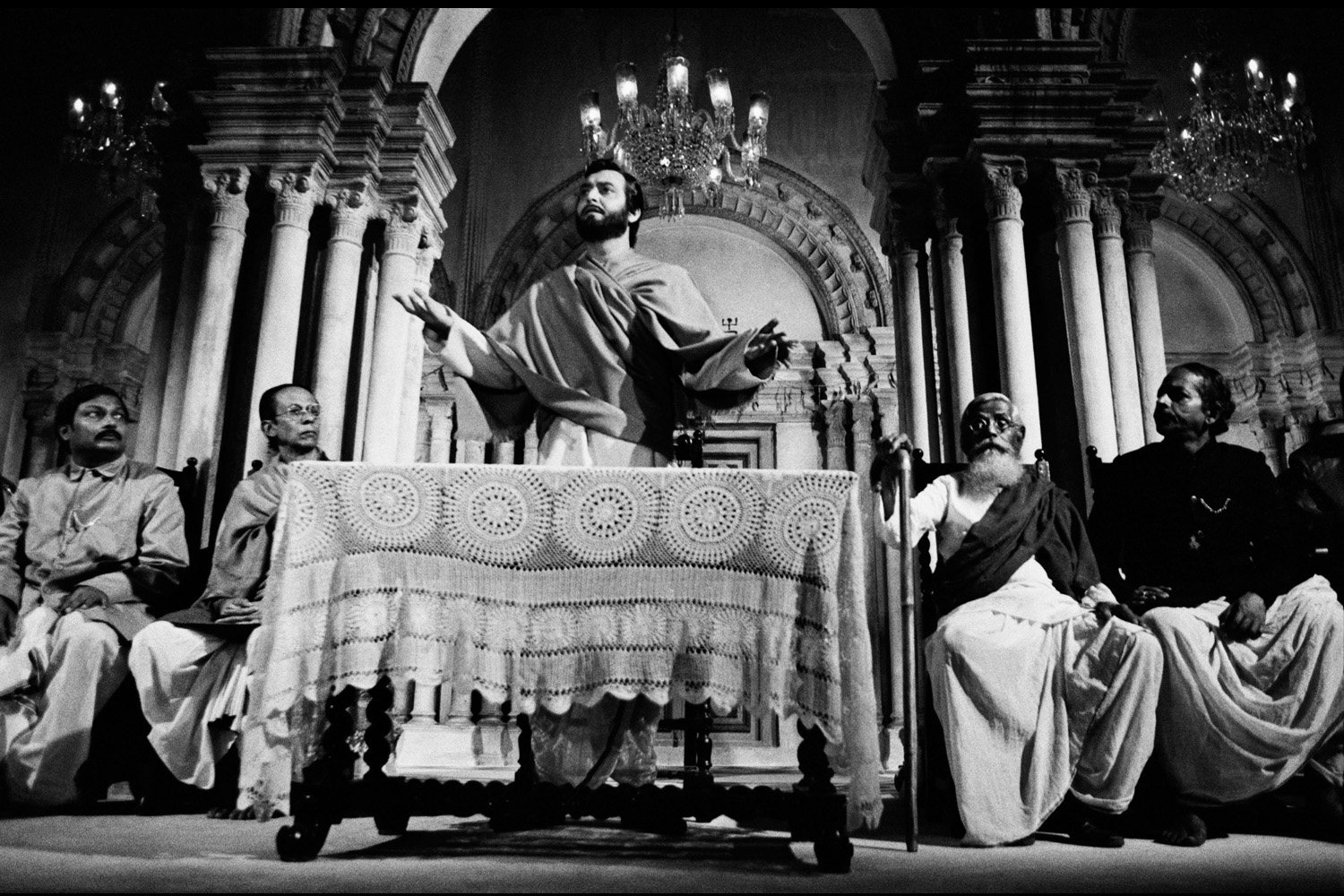

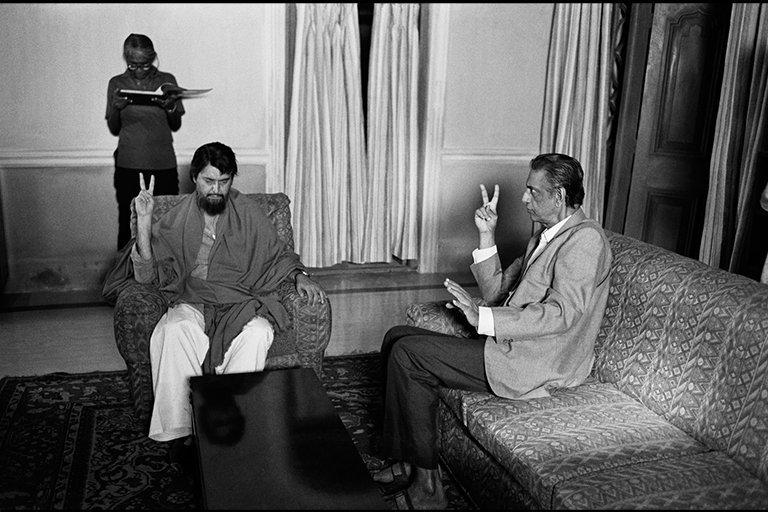

Pratidwandi, 1970

Pratidwandi, 1970 -

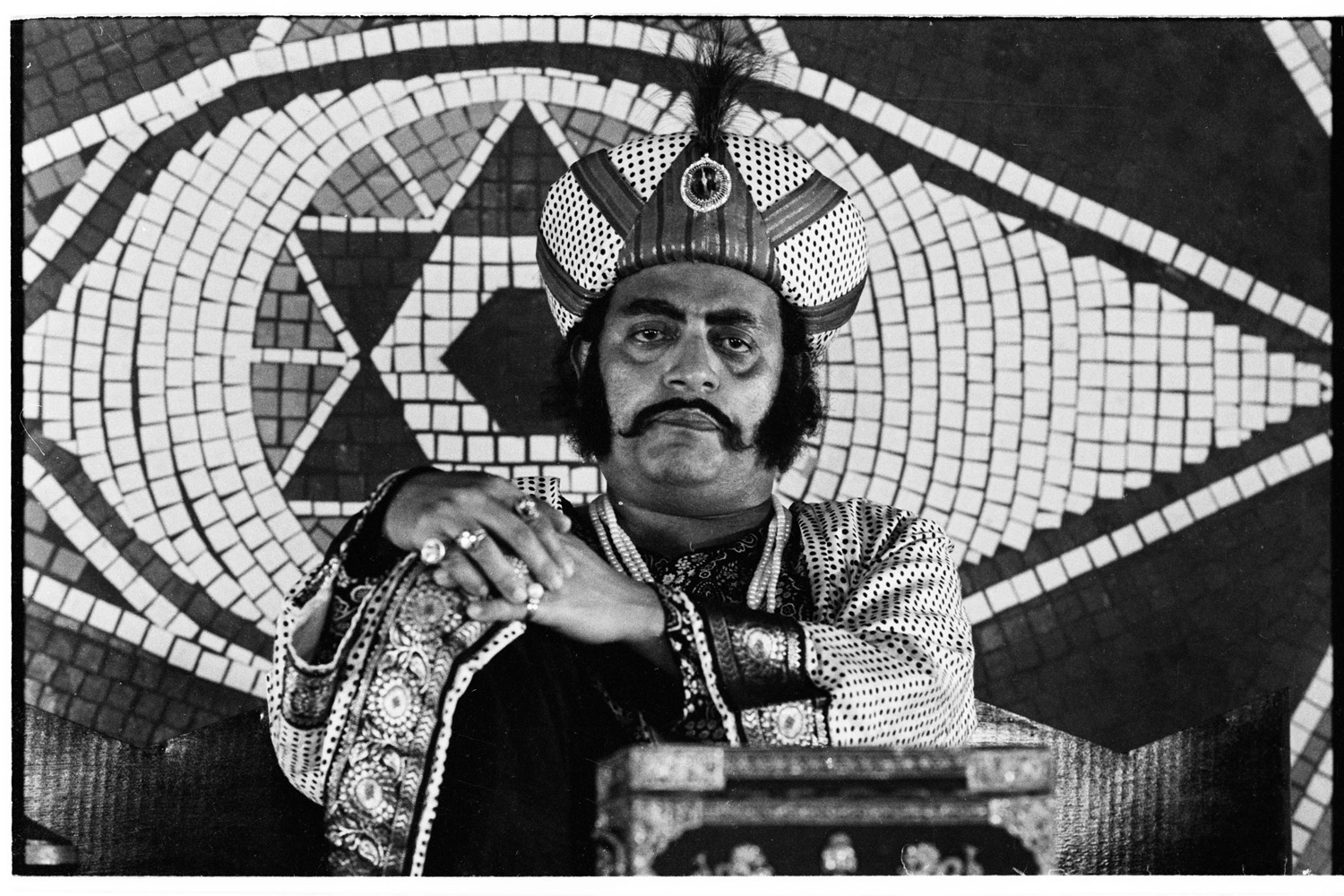

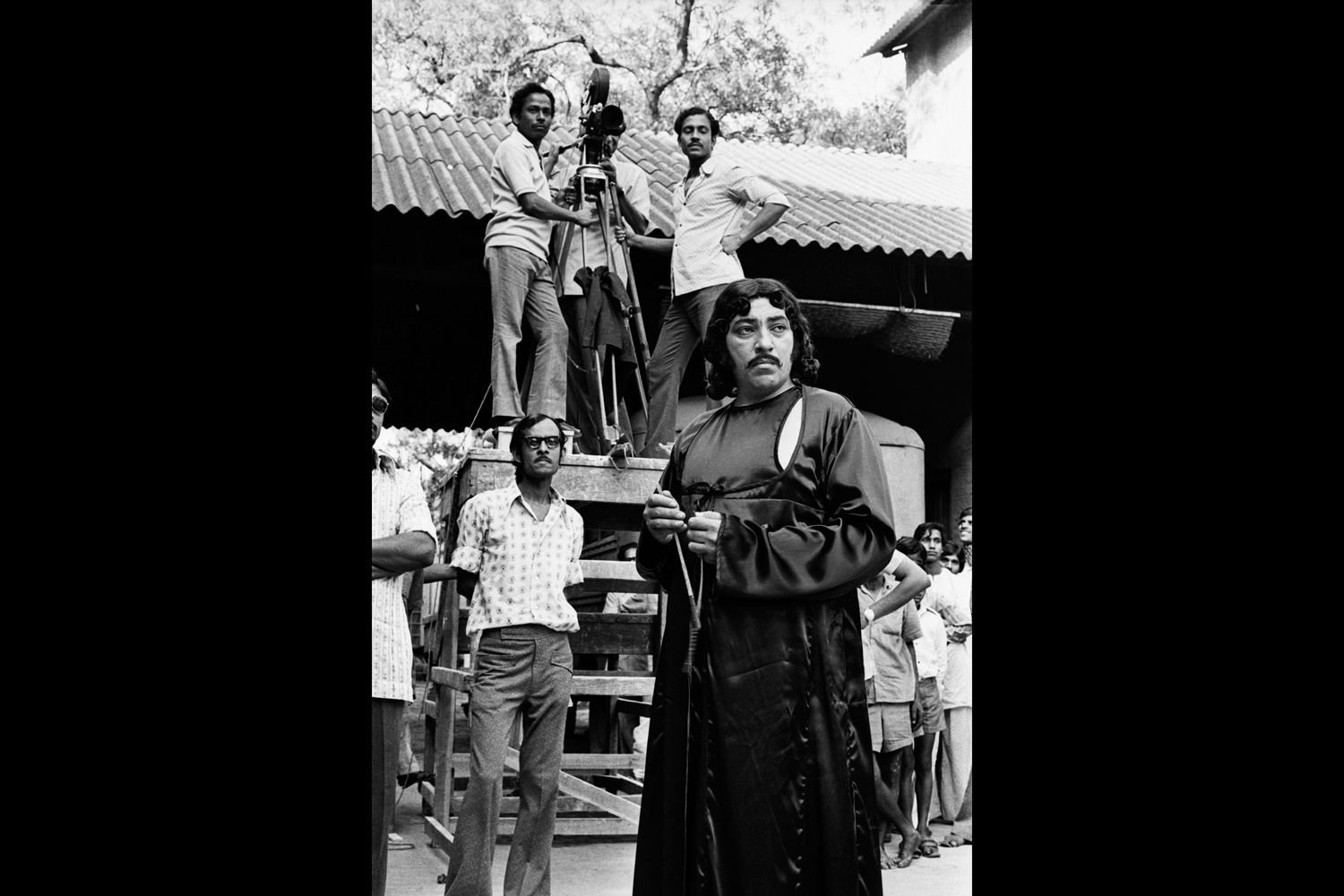

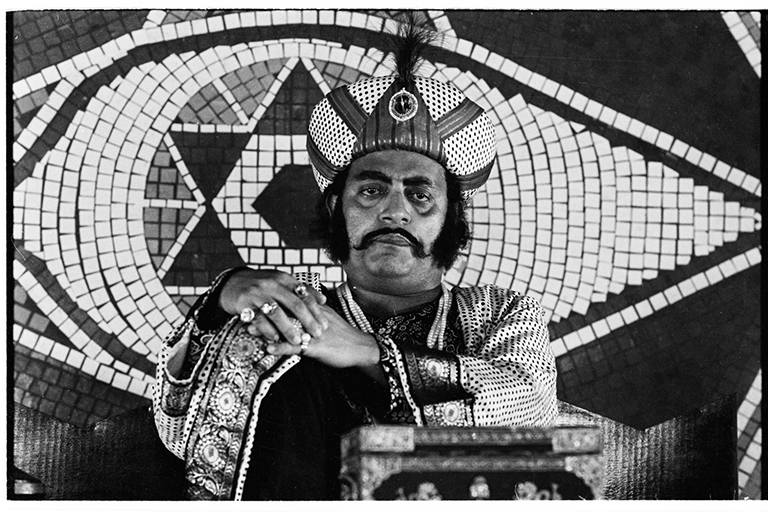

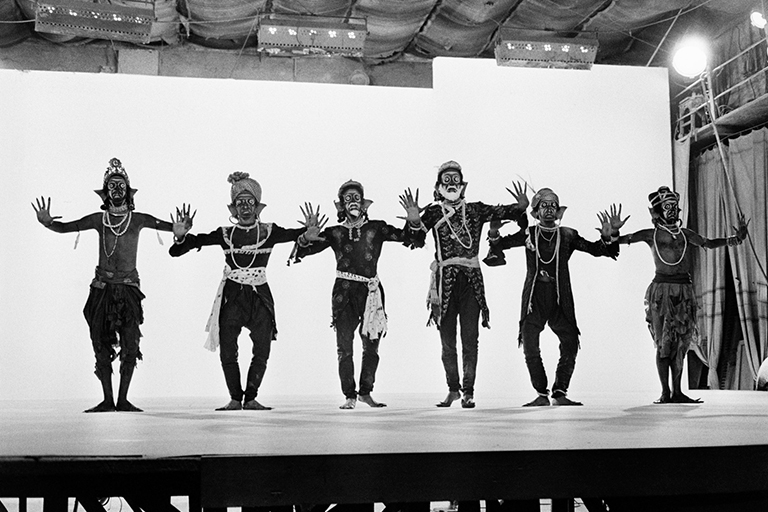

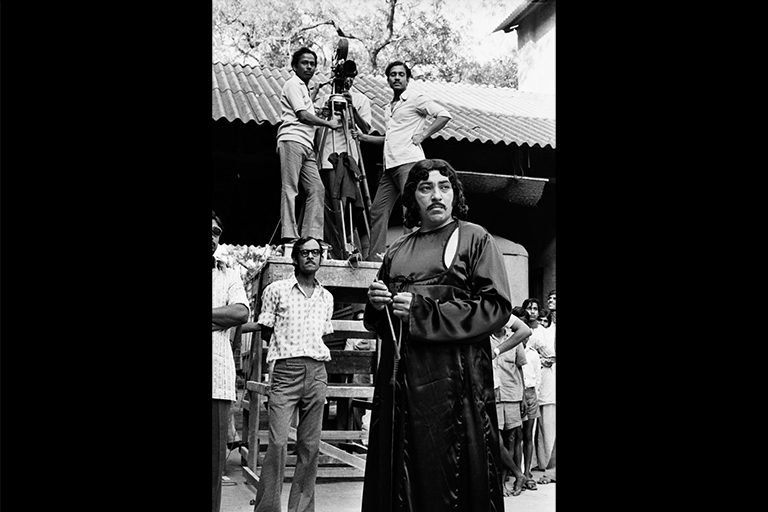

Hirak Rajar Deshe, 1980

Hirak Rajar Deshe, 1980 -

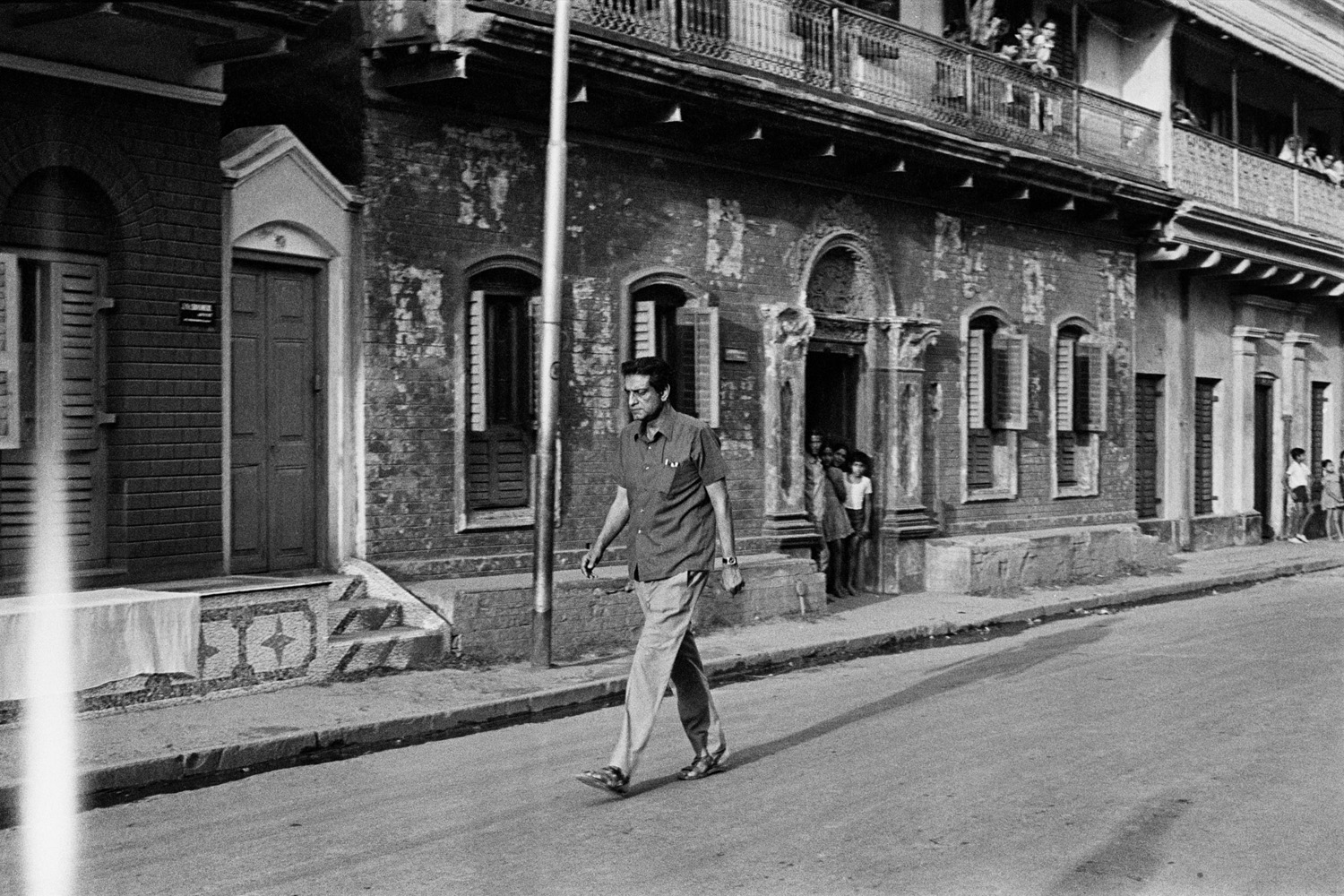

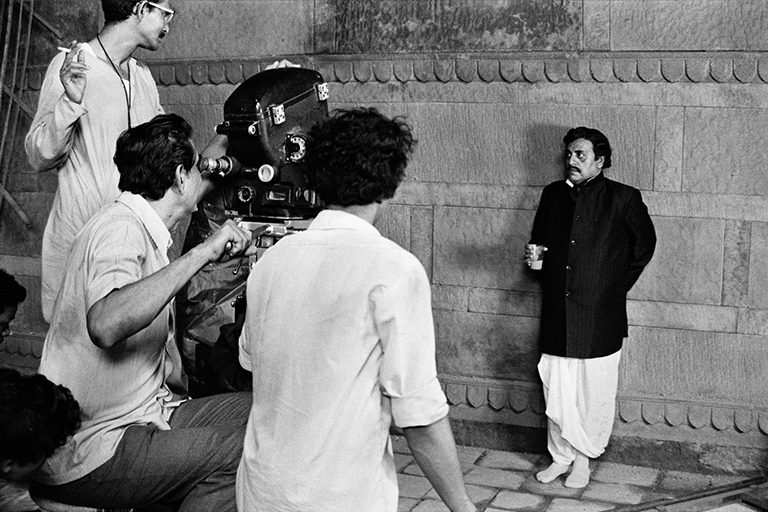

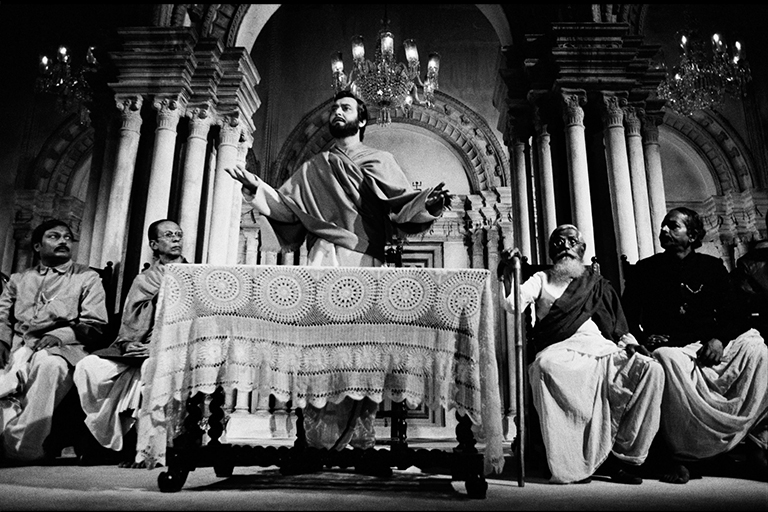

Joi Baba Felunath, 1978

Joi Baba Felunath, 1978 -

Shakha Proshakha, 1990

Shakha Proshakha, 1990 -

Hirak Rajar Deshe, 1980

Hirak Rajar Deshe, 1980 -

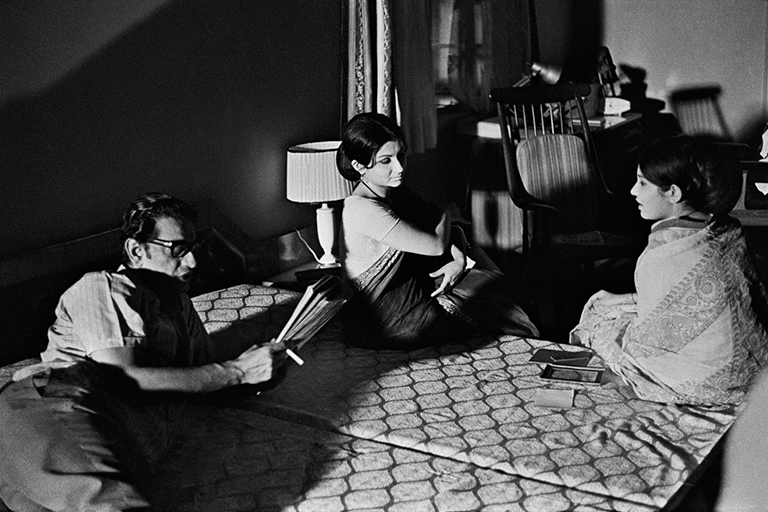

Seemabaddha,1971

Seemabaddha,1971 -

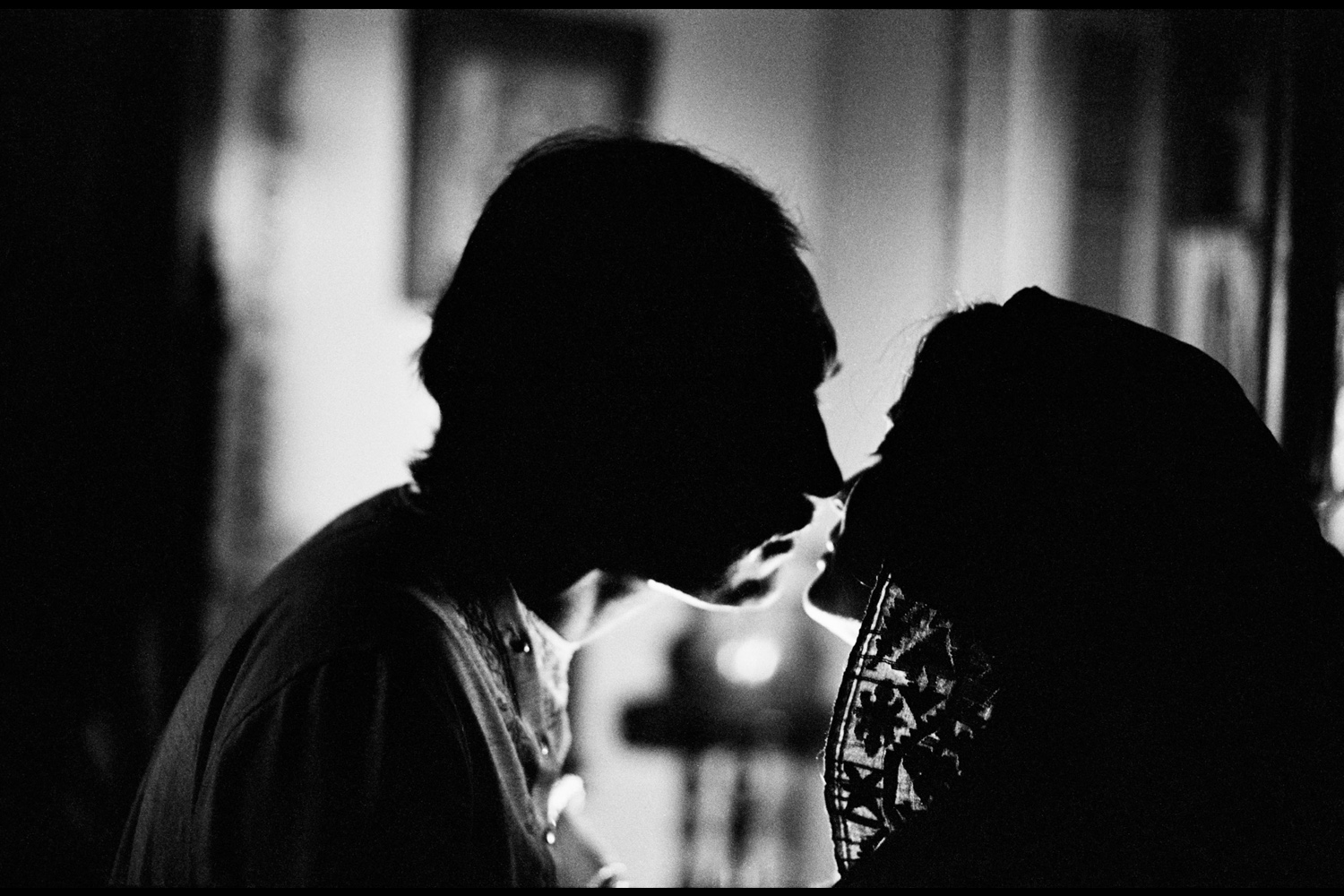

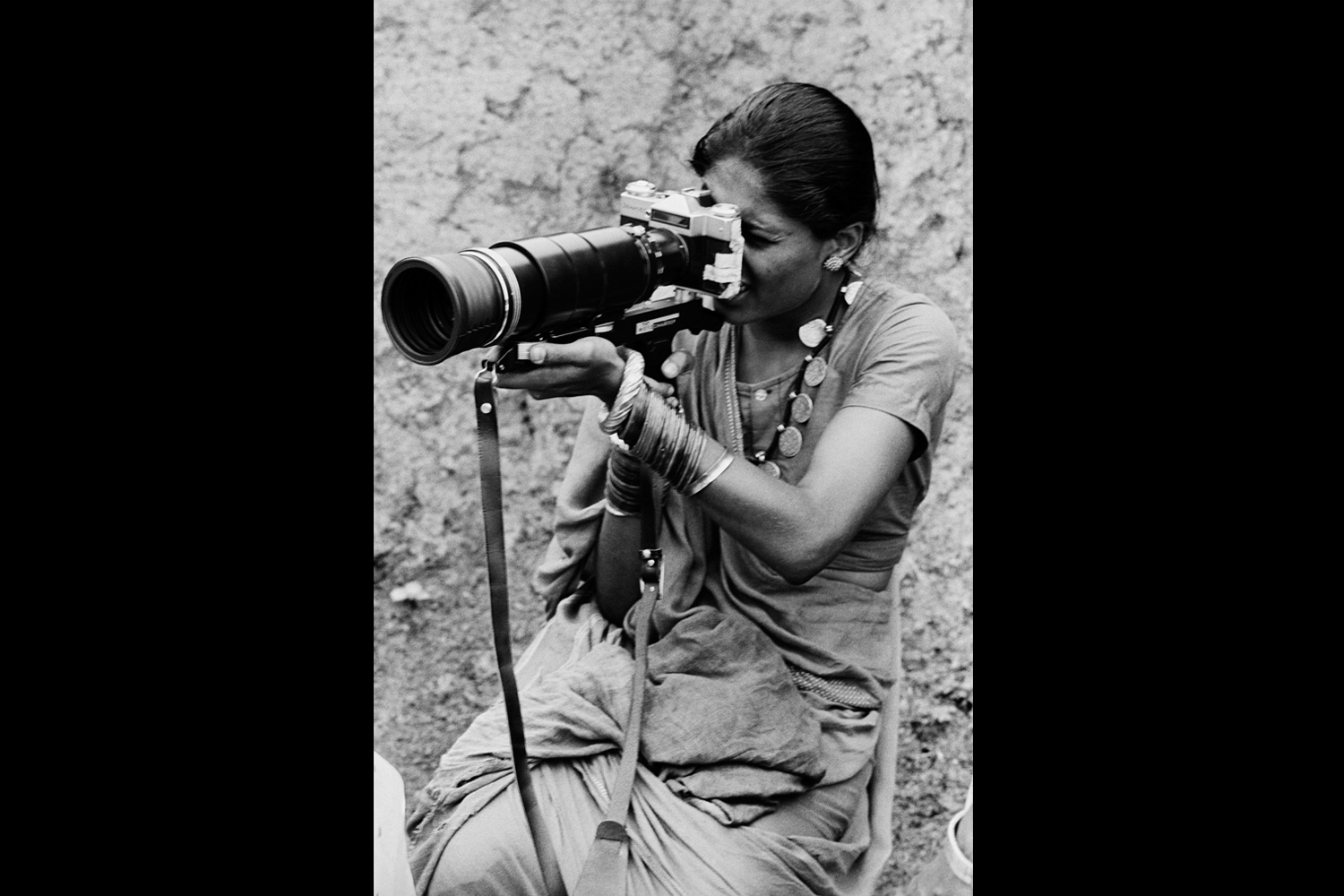

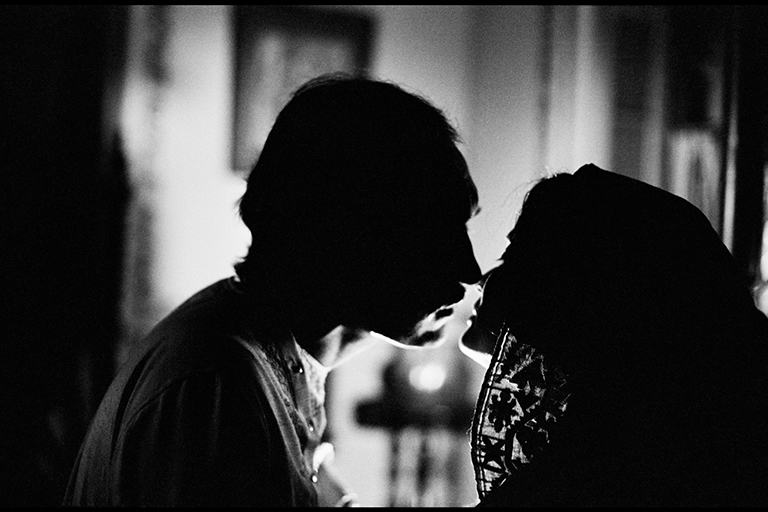

Ghare -Baire,1984

Ghare -Baire,1984 -

Ghare -Baire,1984

Ghare -Baire,1984 -

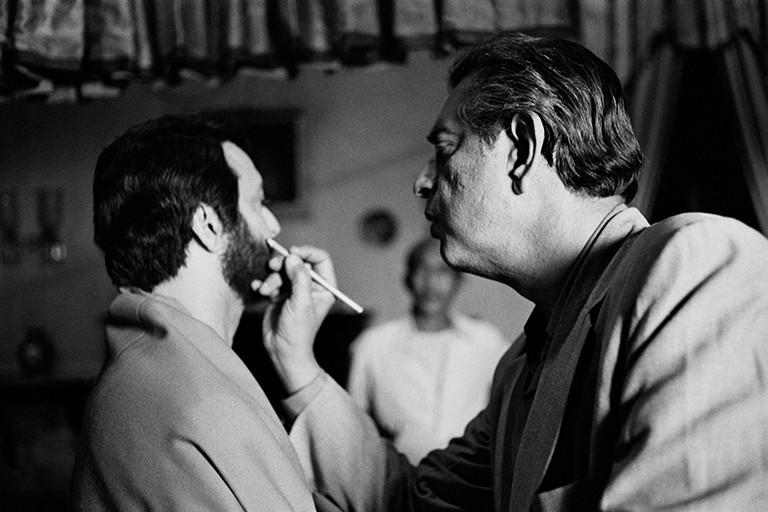

Joi Baba Felunath, 1978

Joi Baba Felunath, 1978 -

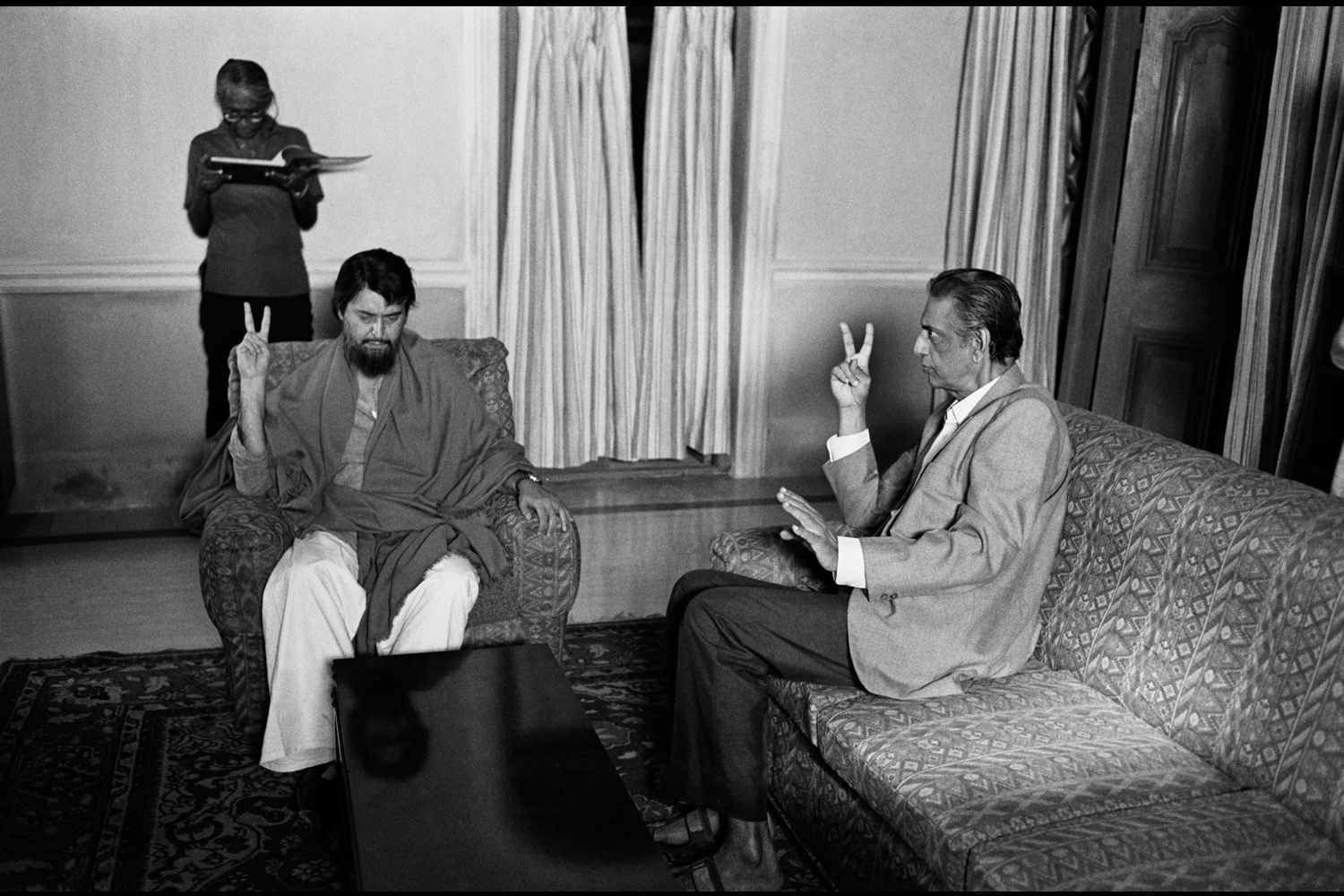

Pratidwandi,1970

Pratidwandi,1970 -

Seemabaddha, 1971

Seemabaddha, 1971 -

Storyboarding for Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, 1968

Storyboarding for Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, 1968 -

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne ,1968

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne ,1968 -

Ghare-Baire, 1984

Ghare-Baire, 1984 -

Ghare -Baire,1984

Ghare -Baire,1984 -

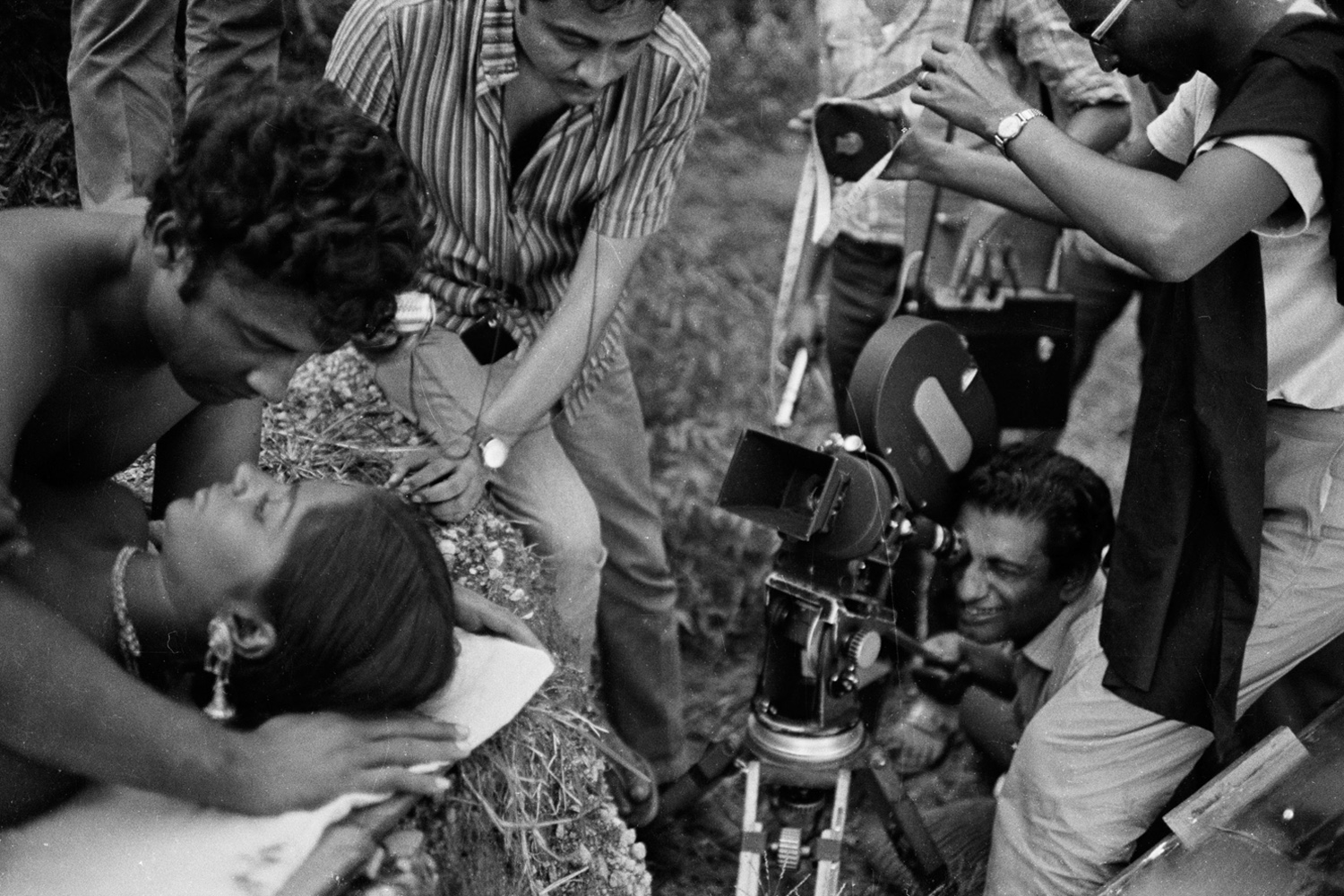

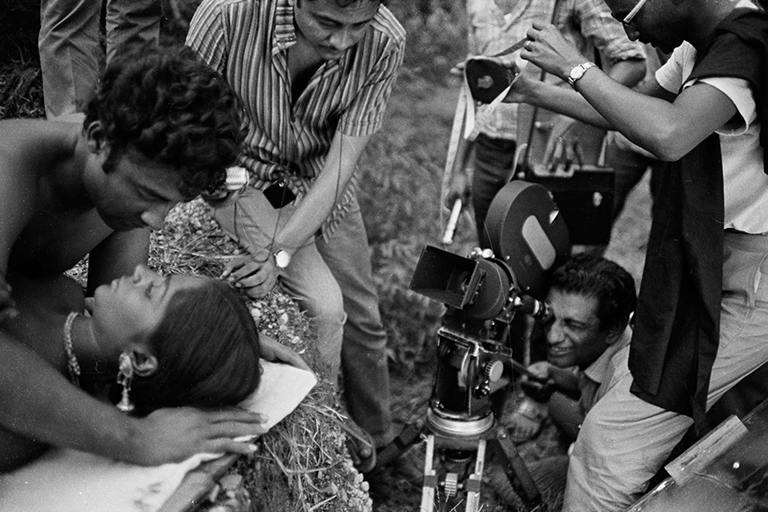

Aranyer Din Ratri, 1969

Aranyer Din Ratri, 1969 -

Seemabaddha,1971

Seemabaddha,1971 -

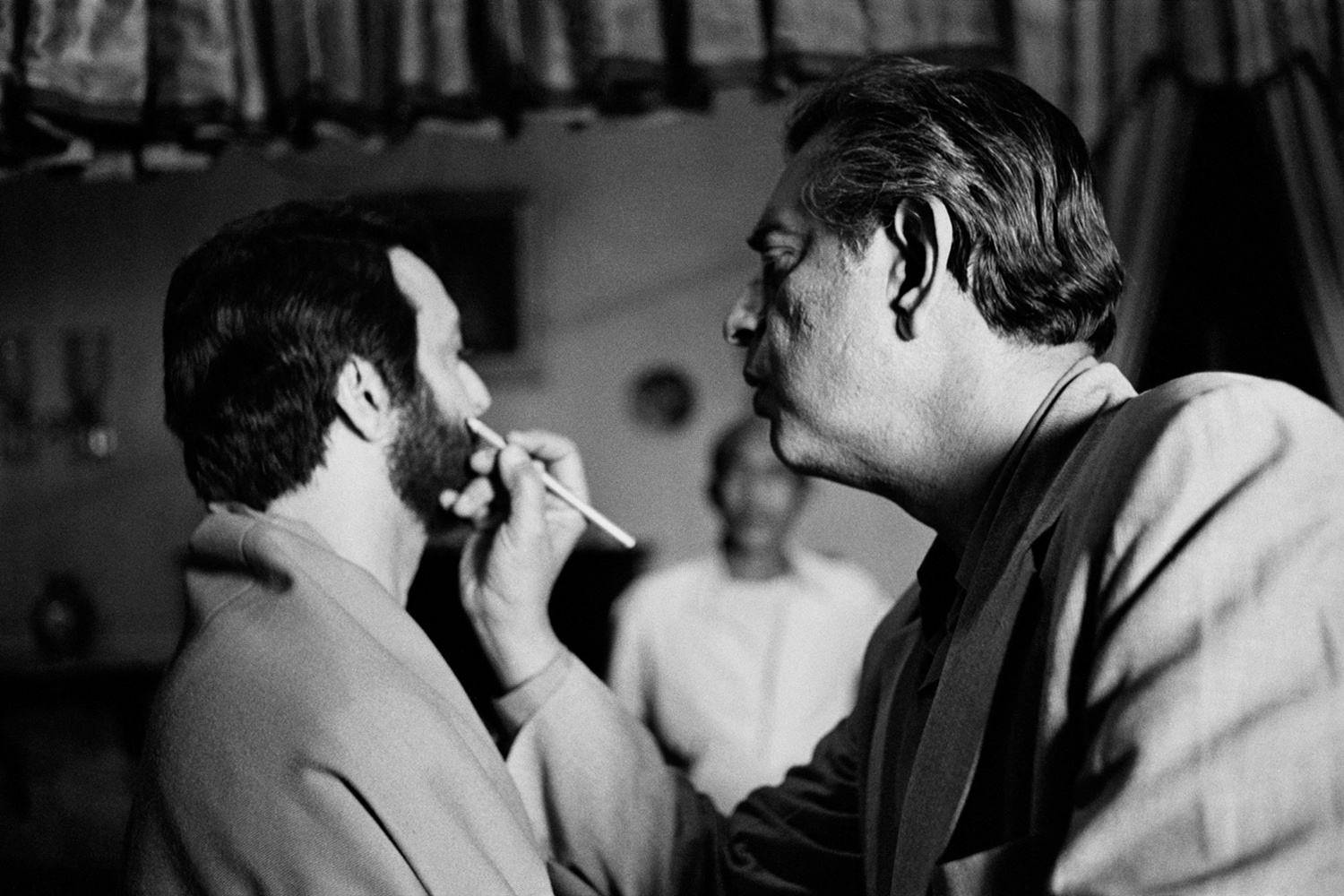

Shatranj ke Khiladi, 1977

Shatranj ke Khiladi, 1977 -

Sadgati,1981

Sadgati,1981 -

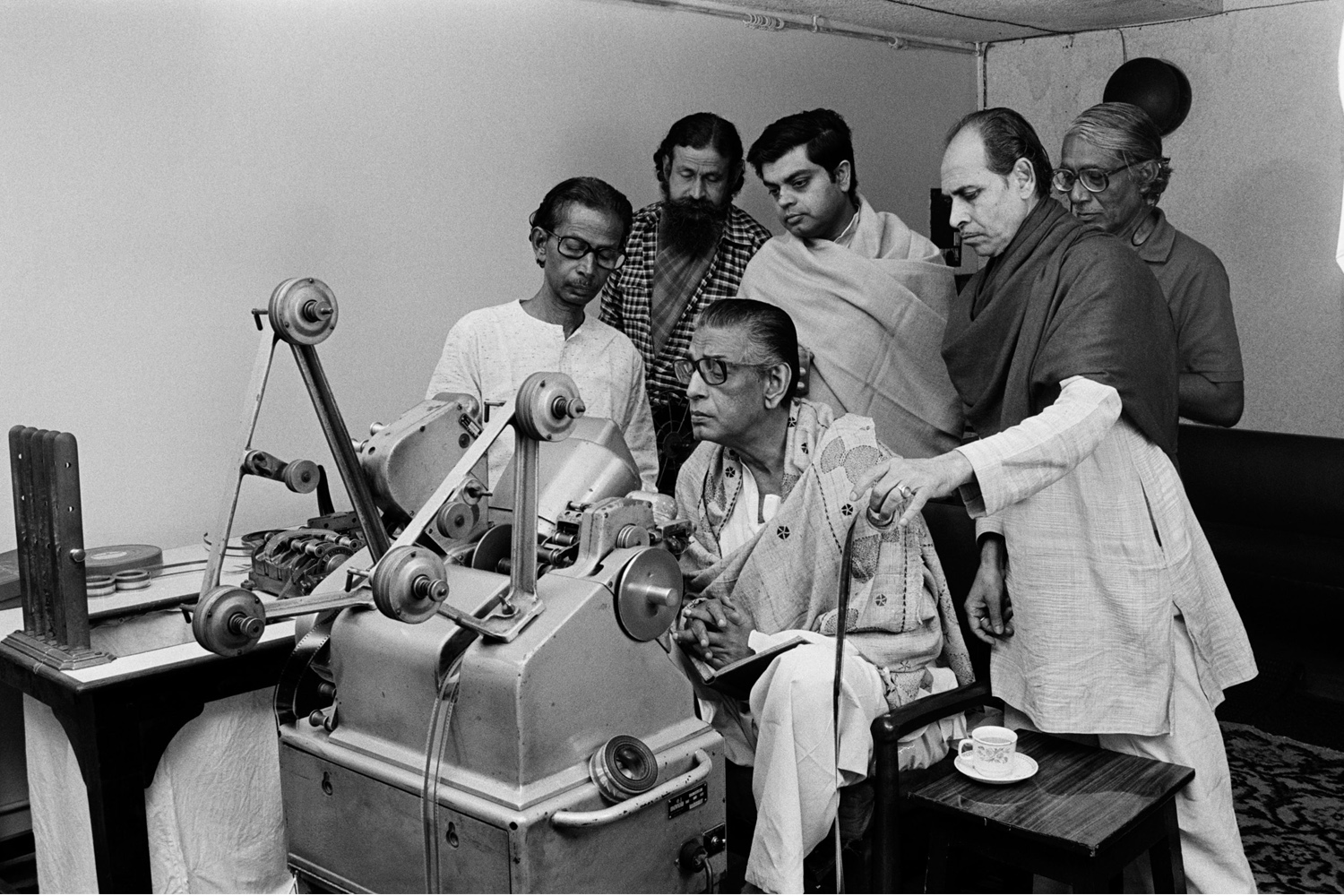

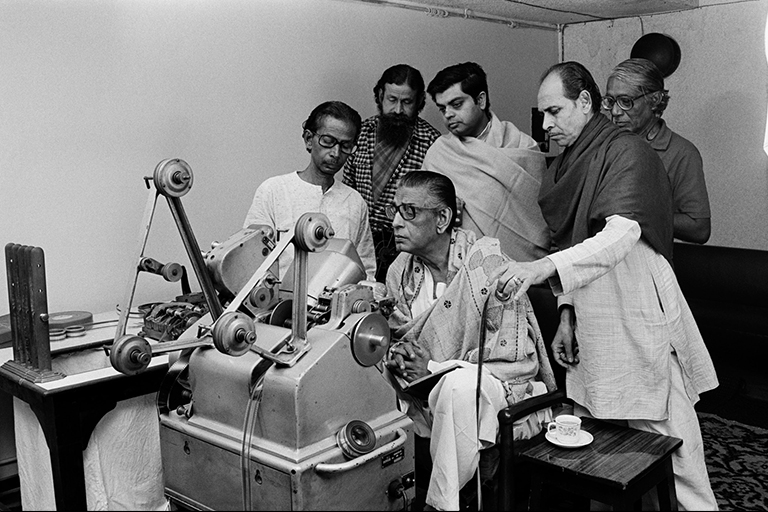

Ray as Editor, 1989

Ray as Editor, 1989 -

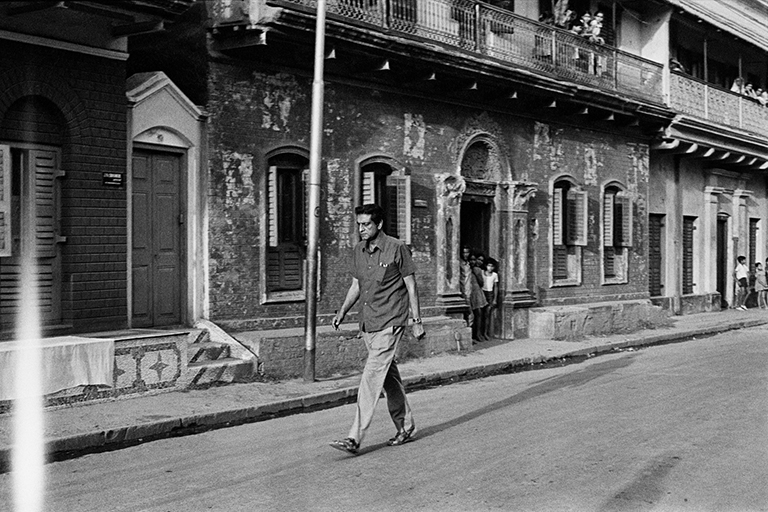

Sonar Kella,1974

Sonar Kella,1974

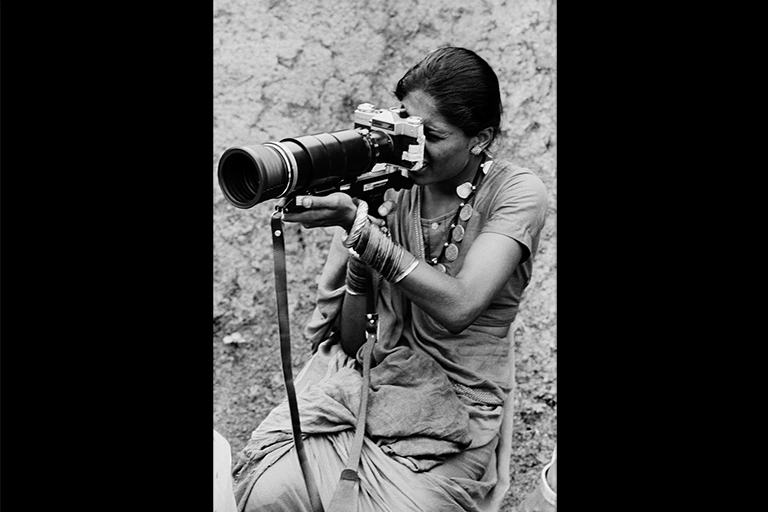

Film and theatre photographer Nemai Ghosh began his journey into the medium with photographs of the filmmaker Satyajit Ray and his movies, which he is best known for. Here is a selection of 24 of these photographs, and an extract from his book Manikda: Memories of Satyajit Ray where he talks of his first meeting with the auteur as well as his first tryst with the camera.

Certain episodes reshaped my life and changed its course entirely. I know not who makes such incidents happen. But whosoever he might be, I am eternally grateful to him. My tryst with the camera is one such episode. Let alone photography, I didn’t even know how to click a camera. It was probably 1967 or 1968. A card session was on in full swing in my house.

Most of my friends, Shubhendu (Chattopadhyay), Bhanu-da (Ghosh), Bansi (Chandragupta), were associated with films. I was never any good at cards. It was sometime in the afternoon. Snacks were being served— the card game and light refreshment going on together. I stood near the window and was munching some muri (parched rice). I was to leave for rehearsals a little later. I was completely immersed in theatre at that time. A friend of mine suddenly turned up and said that someone had left behind a fixed-lens camera in a taxi. Another friend of his had already offered him a sum of six hundred rupees for the camera. Something clicked in my mind, and I told him, “Look, you owe me two hundred forty rupees. You give me the camera and the loan is as good as repaid. Now, you better decide which to choose— business or friendship.” Sure enough, he left the camera with me. I examined it but could make nothing of it. Realizing my predicament, one of my friends, Jaipratap Mitra, an assistant cameraman, decided to help. Bhanu-da suggested he would arrange for film rolls. Thus, with the help of my friends, in a short span of time, I started viewing everything through the lens of my camera.

***

My friends and I were in the habit of spontaneous outings. Let me mention here that this habit has never left me, despite advancing age. To tell the truth, I have never devoted much time to any of my three children. But still they have been brought up well. The full credit for this goes to my brothers and my wife Sibani. In fact, we all lived together. And perhaps it is because of the benefits of living in a joint family that I could, and even now can, take such risks. I met Sibani only after our wedding and we have been together for over fifty years now. Meanwhile, I quit my job, stopped acting on stage, spent thousands on film. When fathers of other children escorted them to examination halls, I would perhaps be out on some outdoor shooting or, intoxicated with photography, on the lookout for some other shoot. My wife has never complained about such escapades. Even when I missed many social functions she took responsibility and made excuses for me. She has always demonstrated ample faith in me and my pursuits.

One Saturday, we boarded a train for Barddhaman— the Canon camera and two rolls of film with me. What awaited us there was beyond our wildest dreams. Our host at Barddhaman—a friend of mine—told us that Satyajit Ray was shooting for Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne at nearby Rampurhat. Robi-da, the director of our drama group Chalachal, was playing an important role in the film. I thought, well I could try killing two birds with a stone: see him on the job, and take his photograph also. We were all quite excited! But having reached there we learned that the shoot had been cancelled for the day. The unit was busy rehearsing a shot, one that later fascinated film lovers the world over— the shot in which drops of water drip from leaves and fall on Bagha’s drum. I don’t know what possessed me then. As if in a trance I felt my finger pressing the shutter on the camera. I finished both rolls of film. We returned to Kolkata the following day. I went straight to the then famous Studio Renaissance in Ballygunj, owned by Bhupendra Kumar Sanyal, more popularly known as Mej-da. Leading filmmakers and creative artists of the time like Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Tapan Sinha and Ravi Shankar used to frequent his studio in those days. Perhaps my association with theatre gave me the courage to go to the studio to develop my films, for there was no reason he would pay any heed to a small fry like me. It transpired that Mr. Sanyal had seen me on stage and liked my performance too. That is why I could gather enough courage to hand over the two rolls to him. He took them and with a grave face entered the darkroom.

I waited in eager anticipation, my heart thumping against my ribcage. Each moment seemed like an endless hour. Mej-da was sure to come out and say in his enigmatic voice, “Well, you were doing fine in theatre. Why then this sudden craze for photography?” Mej-da came out of the darkroom. The first thing he did was pinch me on the belly and then he kissed my forehead and said, “Go ahead, you will succeed in photography.” I couldn’t believe my ears. Had I heard it right? This, after just a few days of holding the camera in my hand for the first time. His words still ring in my ears. Praise from such an experienced man in the field gave me a lot of strength and encouragement.

My excitement knew no bounds. I went on showing those pictures to others. I still vividly remember my joy and surprise at the pleasant response to those photographs. Of course, I did not have the slightest inkling even then as to how the camera would change my life completely. It was then that Bansi Chandragupta, who used to address Satyajit Ray by his first name, suggested to me that I show Manik-da the photographs. “Whom?” I asked him in amazement. He replied, “Why! Manik, of course. He is shooting for Goopy Gyne… these days at Tollygunj. Just drop in sometime with these pictures.”

***

One afternoon a few days later, I dropped by at the studio at Tollygunj, Bansi-da took the packet and said, “Manik, have a look at these photographs.” While Manik-da looked at the photographs, I hid behind Bansi-da, nervously watching the six-foot-two-inch man as he attentively went through the photographs shot by an amateur like me. To say I was excited would be an understatement. He finally spoke. “Who has taken these photographs?” Bansi-da moved aside, pointed towards me and said, “This boy, he is Nemai, Nemai Ghosh.” Manik-da looked at me and in his deep baritone said, “You have done it exactly the way I would have, man, you have got the same angles!” I was ecstatic! I remember having gooseflesh out of sheer thrill and suspense. Much time has passed since then, but that excitement, I can still feel within me. Even today, when I write about that incident I feel that same excitement so palpably. Then he himself escorted me to the sets. And that was my initiation. Soon I found myself in the company of experienced people with modern cameras in hand. It took me a while to get used to the whole ambience. That I could, was perhaps because of the towering personality of Manik-da, which overshadowed everything around him. Completely overwhelmed by all that I saw around me, I was fascinated by my subject— the magnetic presence of the filmmaker as auteur. My lens captured various poses of that intense, self-contained man— the minute trembling of his fingers; the way he sat, walked, the poise with which he stood. I still held in my hand that Canon fixed-lens camera.

***

Some members of Manik-da’s unit used to meet in the evening at a shop in our neighbourhood. Present at such a gathering, were his art director Bansi Chandragupta, sound recorder Sujit Sarkar, production controller Bhanu Ghosh and many others. They usually discussed the minute details of the day’s shooting and also the artistic skills of the filmmaker. In time, I too became a part of the adda. I found myself drawn to it every day on my way back home from my rehearsals. It was like an addiction. However, to begin with, I was only a listener. I wondered when I would know enough to be able to discuss the nitty gritties of working with Manik-da. It used to depress me a little, but I would invariably gravitate to their adda every evening. In retrospect, I realize that this adda acted like an inspiration for me. It would remove the pain of being away from Manik-da. I could feel his personality radiate through his work and the various discussions on it. And that was what kept me going. It gave me a sense of confidence. Someday, I would also be able, like they were then, to tell his story.

***

Meeting Manik-da on the sets was like a dream for me. But there was a big gap between that dream and reality. I was the eldest of my brothers and was married about ten years prior to my first meeting with Manik-da. As the head of a joint family, married, and having children of my own, I had many responsibilities. I was always worried whether I would ever be able to devote myself fully to the fulfilment of my dream. On the one hand, there was my stable, ten-to-five job which would sustain my family, and on the other hand was my first love— theatre. Even in the face of such harsh realities, I visited Manik-da’s set whenever I had spare time. When Bhanu-da told me that Manik-da had framed the photographs I had taken and hung them in his bedroom, I was greatly motivated.

***

After that first meeting when I showed him my photographs, I met Manik-da again on the sets of Goopy Gyne... I was there for about seven or eight shoots. But even within such a short span of time, I saw the man in some of his lonelier moments. Usually, Manik-da never left the sets during lunchtime. Since I was not a member of the unit, I couldn’t accompany the others during breaks. As a result, I studied him from a distance, through my lens.

Once, I saw him standing alone and playing a dundubhi (a kettledrum). On another occasion, I saw him lying on the floor and looking at the ceiling; at times I would see him raising his hands above his head in deep contemplation. I noticed that a sign of his deep anxiety or serious contemplation was biting a handkerchief or the pipe. Sometimes, he would whistle a tune, oblivious to the surroundings. For my photographs of Manik-da which show him laughing heartily, I am deeply indebted to my actor friend Kamu Mukhopadhyay. While I would take different positions—sometimes sitting, sometimes lying, or even standing at precarious angles—Kamu would stand behind me and imitate my pose, making Manik-da break into a loud guffaw. One morning I came to know that he was leaving for Santiniketan the next day by an early morning train, travelling first class. I bought a third-class ticket and boarded his compartment. He was deeply engrossed in reading a book. I was sure he had not seen me. I clicked away. It was much later that I realized that he had seen everything. When the train halted at a station, he alighted, bought two earthen cups of tea and offered me one. Manik-da was an early riser. I used to visit him at his place at six-thirty in the morning. In fact, that was the only time he was free and did not have visitors. Later on, of course, there was no fixed time for me to visit his house. His door was always open. He was always at work. I hardly ever saw him sit idle. Manik-da would get ready by six and come to his drawing room where I would present him with all the contact sheets of my photographs. He would scrutinize these and mark the ones he liked. I still retain those contact sheets. There were occasions when Manik-da would not tick certain photographs that appealed to me. When I asked him, he would explain, like a teacher instructing a student, why those were not good in all respects. Some shots might have been good but the background was not proper. This is how I learnt the art of perfect photography from him.

One thing surprised me then and it strikes me even now. Despite all the name and fame he had attained, he had an uncanny ability to guide any newcomer towards his goal. But he used to get annoyed if someone wanted him to demonstrate how to do something. His mantra was ‘do it yourself’, though he would act as a guide every step of the way. He would judge a man through his attempts and then guide him in a manner that he could easily follow. In my judgement, he was one of the best actors in the world. I can prove it through my photographs.

Excerpted from Manikda: Memories of Satyajit Ray by Nemai Ghosh, courtesy of Harper Collins. You can purchase the book here

These photographs are part of Nemai Ghosh’s archive of nearly 1,20,000 images, built over a lifetime of work, now housed at the Delhi Art Gallery. The gallery is currently showing an exhibition titled ‘Nemai Ghosh: Satyajit Ray and Beyond’. The exhibition showcases Ghosh’s photographs of Satyajit Ray and his films, as well as his lesser known, but equally extensive documentation of both mainstream Hindi as well as Bengali cinema. It is on till January 28, 2013 at Delhi Art Gallery, 11 Hauz Khas Village, Hauz Khas, Delhi, from 11 am to 7 pm. The exhibition can also be viewed at www.delhiartgallery.com

Third Eye

Photo EssayJanuary 2013

By Nemai Ghosh

By Nemai Ghosh

Nemai Ghosh has been the distinctive Satyajit Ray photographer, recording the auteur and his films over thirty years. Besides his photographs of Ray and his movies he has worked extensively in cinema, photographing the films of several directors working in films and television. His passion for theatre has led to a large collection of photographs that forms a pictorial history of theatre in Kolkata over the last four decades, in both Bengali and English. He has also done extensive work documenting tribal life— in Kutch, Gujarat, Bastar in Chattisgarh and Bonda Hills, Arunachal Pradesh. The urban cityscape of Kolkata has also been an abiding photographic interest with him. He has published several books including Satyajit Ray at 70 (1991), with a foreword by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Satyajit Ray: A Vision of Cinema (2005), Barefoot Light (2002) with the NGO Sanlaap, Dramatic Moments (2000) and Manikda: Memories of Satyajit Ray (2011). He lives and works in Kolkata.