-

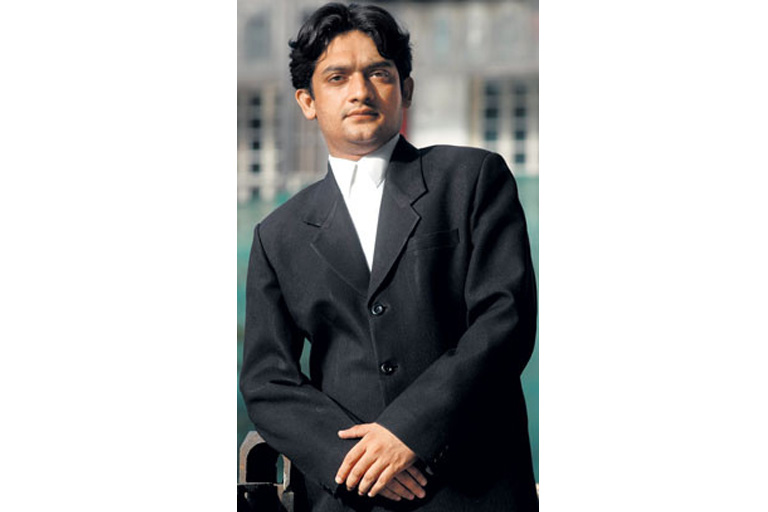

A photograph of Shahid Azmi

A photograph of Shahid Azmi -

A still from Shahid

A still from Shahid -

A still from Shahid

A still from Shahid -

A still from Shahid

A still from Shahid -

Hansal Mehta on the sets of Shahid

Hansal Mehta on the sets of Shahid -

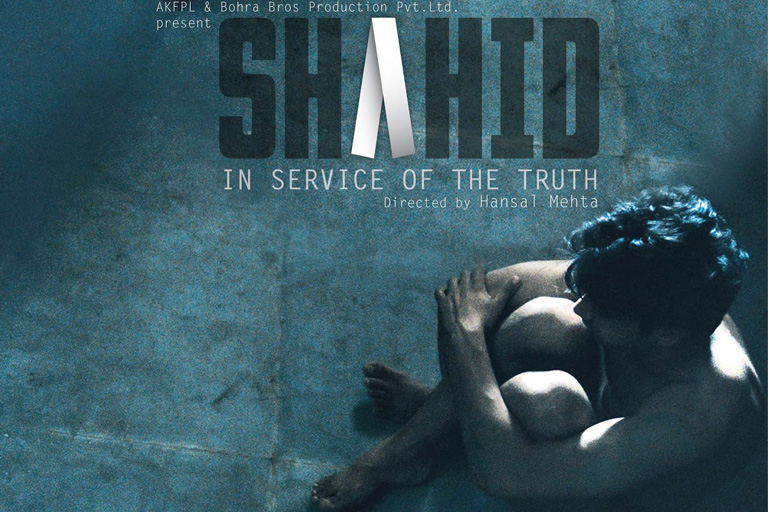

Poster of Shahid

Poster of Shahid

A murder, a movie, and the man in between the two

What’s in a name? The name ‘Shahid’ could mean ‘witness’ or ‘martyred’ in Arabic. In Urdu, Shaheed means martyred, Shahid— witness.

On February 11, 2010, 32 year old lawyer and activist Shahid Azmi was gunned down by four men in his office at Taximen Colony, Kurla, Mumbai. He left behind a wall riddled with bullet holes and splattered with blood.

Next day morning, filmmaker Hansal Mehta read of Azmi’s killing in the front page of The Times Of India. A photograph of that wall, with blood and bullet holes, is all he can remember of the article today. An hour later, Mehta had tweeted: “I have found the subject for my next film.”

It had only been a few days since Mehta had moved into a new flat in Oshiwara, Mumbai. Two years ago, his last film, a Bollywood potboiler called Woodstock Villa, had led Mehta to claim he was “creatively dead”, and move to a house in Lonavla, a hill station a couple of hours away. But the distance from the city wasn’t allowing him to “do justice to his work”. “Also, I was getting very retired with my whole approach to life.”

So Mehta bought his first house (he had lived with his parents before this) in Bombay, the city he had been born and brought up in, or Mumbai, the city it had become. Mehta claims the reason Azmi’s story appealed to him was “a growing concern about the polarized world we live in. Mumbai’s second largest community is that of Muslims. And yet Mumbai is so deeply polarized, that the attitude towards Muslims is that they should be bracketed. They’ve also begun to take this bracketing very seriously— to live in this bubble.”

In 2000, after Mehta released his second film Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar!!, Shiv Sena workers stormed into his office to teach him a lesson for a dialogue from the film that they felt was ‘anti-Maharashtrian’, because it described Khar-Danda, an area in Mumbai, as a place where there was “loot-maar, chori (robbery, thievery)” and “ladkiyon ka adda (which implies prostitution)”. “They vandalized the office. I was thrashed,” is all Mehta says about the incident today. There is more in reports from the time and a blog post written by Mehta himself. His face was blackened with ink. He was summoned to Khar Danda to apologize to 20,000 people and 10 politicians and to kneel and touch his forehead to the feet of an elder there. (They threatened that such assaults would continue if he didn’t do this, they threatened to burn down the home of Kishore Kadam, who had acted in his movie). “There was no one to take up for me,” Mehta says. “(Mahesh) Bhatt Saab called me the day after this and said: We are with you.” The state government then was run by a coalition of the Indian National Congress (INC) and Nationalist Congress Party (NCP). NCP leader Chhagan Bhujbal called to say: “We will protect you,” to which Mehta replied: “The time to protect me has gone.” He felt “really let down by Bombay.”

***

A decade later, when Mehta read about Azmi’s murder, his only contact with the lawyer had been a phone call, where Mehta had asked him about an inmate who had been imprisoned at Mumbai’s Arthur Road Jail at the same time as Azmi. “He said he didn’t have time then, and to call him later,” Mehta remembers. “Perhaps he didn’t want to revisit those days.”

But Mehta has tried hard to revisit those days—that bridge the gap between two points in the life of a man that are on either side of the law, the gap in between witness and martyr—in the two and a half years after he read that report. In these years, claims Mehta, “I have lived with Shahid”.

***

In the beginning, for a few months, he read everything he could find on Azmi. “I wanted to stay with the idea. Nurture it to see if and how it could be a film.”

Sameer Gautam Singh, an aspiring screenwriter from Delhi, had asked Mehta to take a look at a script he had written during this time. “It was a twisted love story. I didn’t quite know how to respond to it.” When he didn’t, Singh sent Mehta a “strongly worded” email with lines like “‘you might not have time for me today, but one day you’ll have a lot of time for me’… or something like that,” Mehta recalls, laughing. When Singh visited Mehta’s office the next day and asked for his script back, Mehta met him and said he didn’t really identify with the script he had written, but asked him whether he would like to work on another idea.

Singh and Mehta’s son Jai did most of the initial legwork (“I felt that, in the beginning, if I went, the family would see me as a person with vested interest— especially since my last movie didn’t lend itself to this kind of film.”). They interviewed Azmi’s family (his mother Rehana and brothers Tarique, Rashid, Arif and Khalid) and colleagues and spent time in the milieu Azmi had lived and worked in. Then Mehta met the family himself. Conversations with each family member opened up a new window: “Each of them had a distinct personal relationship with him.” Khalid, a lawyer himself, provided them with legal papers and pleas his brother had prepared for key cases. “They were almost entirely devoid of any legalese,” says Mehta, whose first film, …Jayate, is based on lawyers as well. “They were written in simple English.”

Key cases such as those of accused arrested under POTA (the Prevention of Terrorism Act) or MCOCA (the Maharashtra Control of Organized Crime Act) which were legislations that allowed for confessions extracted from the accused in police custody—often through torture, deceit or other questionable means—to be admissible in a court of law. Such confessions, even today, result in the imprisonment of the accused in terrorism cases, for long periods, without bail. Accused like Arif Paanwala (2002 Ghatkopar Bus Bombing), later acquitted, or those accused in the 7/11 Mumbai local train blasts, the 2006 Aurangabad Arms Haul, the 2006 Malegaon Blasts. Azmi secured 17 acquittals in a short-lived legal career of only seven years. Acquittals of men who had emerged out of crazed media furors and shoddy investigation work by enforcement authorities under pressure to deliver, who would dish out mug-shots that would be plastered on TV and in print, to create our poster boys of hatred, to be hated, a few for every season of terror strikes. In defending these poster boys,Azmi became something of a poster boy himself. Standing steadfast as witness to their cries in the wild, he became their martyr. His last well-known and well-hated client was Faheem Ansari, accused of conspiracy in the 26/11 attacks. He was acquitted on 3 May, 2010. But his name was finally cleared of any complicity in the attacks by the Supreme Court on August 29, 2012, two years, six months and 18 days after Azmi’s death, and 11 days before Mehta’s Shahid premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Raj Kumar Yadav plays Azmi, an actor, not a star, even though not casting a star meant that Mehta had to compromise significantly on the budget of the film. Yadav was made a part of the research. He accompanied the team to lower courts, where they sat in on sessions and often surreptitiously clicked reference photographs from their phones to aid the authenticity of what they would create.

Mehta remembers that, while researching …Jayate, it had occurred to him that courtrooms were almost exactly “like fish markets”. But in the film itself he had shown the proceedings as sanitized and respectful, as they are in Bollywood, or even Hollywood, legal dramas. In Shahid, Mehta has tried to undo this. Lower court arguments, even those involving terrorism cases, often culminate in spats between advocates, on the court floor, that you cannot help but laugh out loud at. The fact that this laughter distracts you momentarily from the fact that a human life hangs in balance, makes the trial all the more horrific when you return your attention.

Khalid also provided the team with material that his brother and he had studied from for their LLB exams. Not thick law books, but printed and stapled ‘notes’, that sell faster than AIRs (All India Reporters that record the judgments for each and every case) at legal book stores. These notes concise each subject into 50 odd pages. Most students around India are familiar with them, many swear by them. Mehta filmed Yadav reading these notes diligently, when he wanted to show Azmi preparing for his law exams. He filmed Yadav in the same room that Azmi had once studied in, and he filmed him in other real locations, like the Dongri office of the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, an NGO providing legal aid to poor accused in terrorism cases, that Azmi fought many of his cases in consultation with.

***

The other side was trickier. Azmi is said to have joined a training camp in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir after the 1992 riots. “I had seen policemen killing people from my community. I have witnessed cold-blooded murders. This enraged me and I joined the resistance,” a 2004 report inThe Times Of India quotes him as saying. He was arrested by the Govandi Police on charges of communal violence, under TADA or the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (which was finally repealed in 1995) when he was 16 (this was despite the fact that he was a minor). Additional charges framed against him, after he was arrested, were that he was conspiring to assassinate Shiv Sena supremo Bal Thackeray and J&K Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah. He was in jail for over five years, till 2001, when the Supreme Court acquitted him. It was in prison that he completed his graduation, as well as a post-graduate degree in Creative Writing. It was after Azmi was released that he studied law.

“The details about his time in Kashmir are very sketchy,” says Mehta. “No one (among his family and colleagues) talks about it.” Still, Mehta found one person, whose name he does not wish to disclose, who spoke about this time. “Especially about him missing his home, and his disillusionment with the movement,” Mehta says. Similarly, there were not many people who could recount the details of Azmi’s time in jail, though Mehta says he knows from what he has gleaned that it “transformed him”. Mehta says: “A lot of the film is based on what I imagined his journey to be.”

There is a scene in the film where Azmi has his face blackened by right wing goons. There is no account of this ever actually happening, though he did receive endless death threats for the cases he took up. But as Azmi saw himself in so many young men he was trying to save from unwarranted torture and imprisonment, so did Mehta see himself in Azmi. “That incident, in the film, was fiction. It was my connection with Shahid, who was persecuted in different ways,” Mehta says. “The truth of the matter is that that incident, what happened with me in 2000, has never left me. And that the violation of our basic right to expression has become even more deep-rooted today. When I see someone being violated, I go back to that incident.”

Mehta is happy with the fact that Khalid said, after watching the movie, that it was “95% accurate”. “When you see Raj Kumar, you do not remember him, you remember the character,” says Mehta about why he thinks Yadav has been an excellent choice for Azmi.

But there might be another reason. “As I listened to his words, I couldn’t help but fear for his future,” Letta Tayler, a researcher in the Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism program at the Human Rights Watch (HRW), had said about how she felt when she met Azmi in 2009. “The light he radiated seemed impossibly bright.” Perhaps the truth of the matter is that no actor, nor star, could have played Azmi. Even the best method actor would be at a loss as to how to recreate an aura that emerges out of a lifetime of pain, grit and inconceivable optimism (Azmi was not, as many self anointed saviours try to be, the light at the end of the tunnel. He was the light in it). Yadav, in his studied portrayal, has done the next best thing— paid a simple, wholehearted tribute to the man who is no more.

In a similar vein, Mehta’s script, which was initially non-linear and complicated (“When I showed people a linear script they felt it would be too long and boring”), was returned at the editing table to an unbroken storyline by his editor Apurva Asrani (who also has writing credits on the film). “He started a non-linear cut, then stopped, because he felt it wasn’t working,” says Mehta. “So, like with a documentary, we built the narrative on the table.”

Shahid‘s producer, Sunil Bohra, came to the shoot one day and asked Mehta: “What kind of director are you? There are no top-angle shots, no dolly, no rig. I’m telling you— you can take these things.” Mehta didn’t need to. “When he (Bohra) saw the film, he got it,” he says. To have stylized Shahid, this rare narrative of our times—not Gandhi, not Jodhaa Akbar, but a narrative that has been woven by us, that we continue to endure—would have been inappropriate. Mehta has played it straight. “I did not want to show off,” he says. “I did not want to manipulate the audience.” Thankfully. How much of life do we see through top-shots anyway?

Also thankfully, Mehta claims he hasn’t had to make any cuts to the film to have it passed by the Central Board of Film Certification (though a crew member reveals that the refusal to remove a scene that shows Azmi being tortured on arrest may have gained him an A certificate). Of course the moral police may come knocking on his door again, but “this time,” says Mehta: “I am not afraid. I will not take it lying down.”

So, unlike in so many other cases, once Shahid releases we may just see the same film that was lauded at so many festivals. Festivals where, in front of cinema theatres full of people, Azmi has been shot, right at the beginning of each showing. The film goes on for a gripping two hours, at the end of which the scene plays out again leaving, each time, a wall ridden with holes.

Who were the men who shot Shahid Azmi? Who sent them? These are the first questions Mehta has been asked by audiences at each festival. “The sad part of our investigation processes is that you never know what really happened,” he says. “There is only speculation. And there are vested interests (that misdirect the investigation).” He also says: “For me, who killed him is irrelevant. It angers me enough that someone walked into his office and killed him.” He adds: “There are mainstream films, like Kurbaan, that provide you with both the problem and the solution— often a half-baked solution. What do you take back from the theatre? Nothing!”

***

Perhaps it is just as well that Mehta didn’t delve into who killed Azmi. Doing so could have been read as a filmmaker commenting on a subject that was sub judice by the Court and, like Black Friday (directed by Anurag Kashyap, one of this film’s co-producers), Shahid’s release might have been delayed endlessly. Mehta, however denies that this was a consideration. He claims his decision was purely creative. And it pays off well. The identity of his killers, like the proverbial elephant in the room, begins to bother the viewer. The blood stained wall looms large and follows you out of the theatre. Perhaps this is Shahid‘s greatest strength. By not telling you, it makes you want to know.

In February, 2010, the month in which Azmi was murdered, four accused were arrested under MCOCA in connection with the case. They were Devendra Jagtap, Pintu Dagale, Hasmukh Solanki and Vinod Vichare. The police claim the accused were members of a gang run by Bharat Nepali. Four months later, in June, Azmi’s peon Inder Singh, the only key witness in the case who was present at the office, received a threat call that was traced to Gujarat. In November, the same year, a gangster was gunned down by suspected Chhota Rajan henchmen in Bangkok. The police have now confirmed this was Nepali.

On January 20, 2011, a MCOCA Court dropped its special charges against the accused because it found no evidence of the fact that “pecuniary gains were made in the crime, a mandatory aspect for MCOCA charges.” Then, on April 8, 2011, Crime Branch officials apprehended a man, named by the press only as ‘Munna’, with a gun and a few live cartridges at the Kala Ghoda Court. Munna had allegedly arrived there, with an accomplice, to free the four accused who were in a hearing at the Court then.

On July 23, 2012, the Bombay High Court granted bail to Vichare, against a personal bond of Rs 50,000, because he was not “shown to be present” during the assassination.

***

“Do you think Mohamed Atta is a big terrorist? The guy who flew the plane into the World Trade Centre?” asks Mehta, when speaking of who could have killed Azmi. “Or Kasab? The real perpetrators, who gave the orders, are sitting pretty.”

Azmi’s death has been clouded by its share of conspiracy theories. There is a theory that he had received phone calls from underworld dons who were Muslim, congratulating him on his work, and that this angered Hindu gangsters such as Bharat Nepali, or Chhota Rajan, who got him killed. Another rumour is that intelligence agencies weren’t happy with the way he was blowing holes into the State’s cases, and making the enforcement look bad. And that he was aware of some greater conspiracy underfoot, that they wanted to hide. And so they wanted him out of the way.

Unlike Oliver Stone’s JFK, Mehta’s Shahid isn’t an investigation into any of these theories. Perhaps because, unlike JFK, which was released 28 years after the president’s assassination, it has only been three years since Azmi passed away, and there is no District Attorney called Jim Garrison asking the tough questions.

Or maybe there’s the irony. That Azmi was our Garrison, our witness, now martyred. “Human rights are violated by the most powerful,” says Mehta. “And the people who fight it have no protection.” Shahid is not a whodunit, but about a larger picture, he says. “If you ask me,” he says. “I think we killed Shahid.”

Shahid Azmi Haazir Ho

ArticleApril 2013

By Rishi Majumder

By Rishi Majumder

Rishi Majumder is Senior Editor at The Big Indian Picture