-

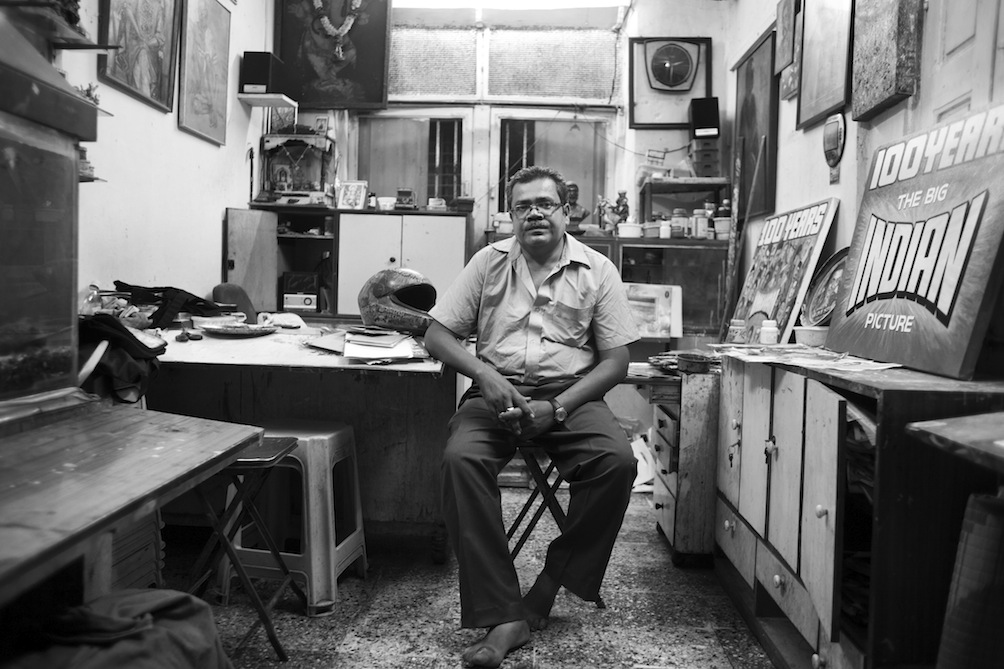

Ramakant Fadte (C) Vidura Jang Bahadur

Ramakant Fadte (C) Vidura Jang Bahadur -

Ramakant Fadte (C) Vidura Jang Bahadur

Ramakant Fadte (C) Vidura Jang Bahadur -

Ramakant Fadte (C) Vidura Jang Bahadur

Ramakant Fadte (C) Vidura Jang Bahadur -

Hand Painted poster by Ramakant Fadte

Hand Painted poster by Ramakant Fadte -

Hand Painted poster by Ramakant Fadte

Hand Painted poster by Ramakant Fadte

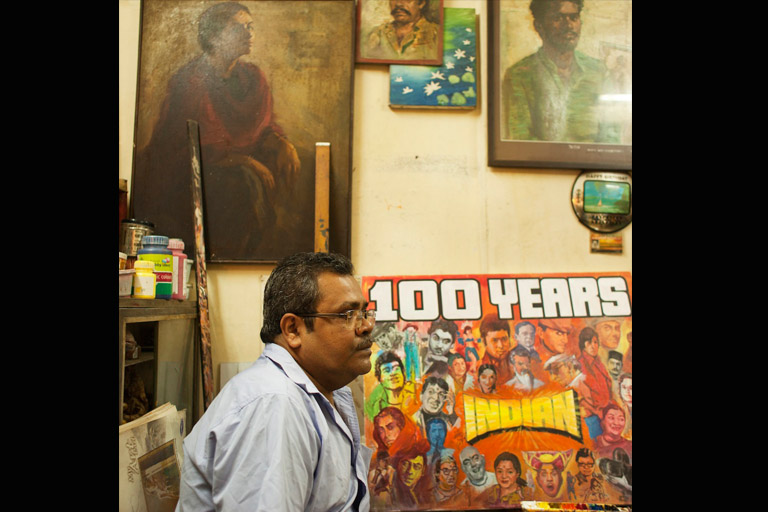

When I looked for ‘Ramakant Fadte’ on Facebook I found a painting of Kishore Kumar and a bespectacled E.T. peering back at me from a profile picture. His previous profile picture had Fadte looking as if he had been photographed at gunpoint, wearing a brown silk shirt, his greying hair combed back, with a pair of rimless eyeglasses and a moustache. His wide eyed expression is understandable. In the five years that I’ve known the 48 year old artist I have always seen him dressed casually, in a plain cotton shirt, a pair of dark trousers and sandals. His hair has always been tousled. But there is nothing I have seen him wear more easily, on his chubby demeanor, than a shy smile. It was only natural that he chose to replace this photograph of his with a painting of ET and Kishore Kumar, so at home with one another. The former profile picture also portrayed a miniscule section of the room that Fadte lives and works in in Mahim, Mumbai. There is a portion of wall, and a strip of an old bulletin board that has some of Fadte’s paintings pinned on it: an impressionistic portrait of Akshay Kumar and the photographs of boxes Fadte had painted with images from Bollywood posters for a client, cut abruptly out of frame.

This is as much as the 160 by 160 pixels of space given by Facebook for a profile photo will allow him to show. Here, as in the room itself, Fadte has struggled to fit himself and his work in. The 16 by 8 feet room is one of 47 in a decrepit seventy year old building whose name spares no irony: Roopwala (Beautiful) Terrace. It seems to end even as you enter. On the other end are 2 showcases crammed with images of Hindu Gods, fifty odd bottles of fabric paint, a medley of Ganesha idols, toy cars, trinkets and curios. On the walls are the bulletin board, impressionist landscapes, abstract art, a black and white photograph of his grandfather Tatu Fadte, a large garlanded portrait of Ganesha and other portraits Fadte has painted himself: a worker he found reclining on the pavement near Mumbai’s Opera House, wearing a shirt and a lungi; a bearded friend whom he painted wearing a bottle green kurta, which won Fadte a state award; an unsmiling portrait of his wife’s sister, painted many years ago.

Fadte and his wife are separated now, but her traces abound. A loft above Fadte’s door is stuffed with canvas frames—some broken, rolls of wire, and pieces of natural wood art that his wife’s uncle made, by way of a hobby, and left here for Fadte to try and sell. Three of these wood art pieces are inside a 5 by 2 feet aquarium that takes up more space than anything else in the room. This has 15 fish, from among 5 species in hues of red, orange, silver, grey and black, along with a tiny white plastic fisherman with a Thai hat. Fadte had bought 6 aquarium sharks to keep in this aquarium. Once the first shark seemed about a foot long Fadte had to give them away to an acquaintance with a larger fish tank.

The room seems exactly as I had seen it first, five years ago. The only change I notice is the presence of an 11 inch Acer laptop. The only change I notice in Fadte is an occasional swelling of his right foot, caused by water retention, due to severe diabetes.

Almost every night, at 10, Fadte begins to watch a film on his laptop with a glass of Prestige gin and water. Sometimes he watches only half the movie. Sometimes he watches the same film over and over again. The two movies he has watched the most are Splash and The Invisible Man. Fadte says he doesn’t know why he likes these movies. His favorite scenes from them are “the scene where the woman becomes a mermaid in the middle of New York (in Splash)” and “the scene where the invisible man dresses up in his clothes, shoes and gloves, wraps his face in bandages and wears a pair of dark goggles so he can leave his room”.

But I think I know why he likes these scenes and these movies: it’s because they’re about trying to fit in. The sharks couldn’t fit in. Fadte has tried to.

An only child, Fadte moved into this room with his parents when he was eight. They moved from an even smaller residence near Ruparel College, less than a kilometer away. When Fadte was 11 his father Narasinha Fadte, a signage painter, took him to a poster painting studio called Visual Arts, just a block away, so he could apprentice there after school. Visual Arts, one of the city’s most popular studios for poster painting, was spread over 6000 square feet of space. “Artists would work on eight banners at a time,” Fadte remembers. “Each 20 by 10 feet in size.”

Fadte would be at the studio from 8 to 12 every night, five days a week. The head artist at the studio was Manohar Gawde. But Fadte was assigned to Narendra Dewulkar, who did the first sketches for the posters. Fadte remembers poster painting being divided into “sketching, the wash and fill-up (done by junior artists) and the finishing”. Dewulkar made him practice sketching the faces and bodies of actors on a notebook. After a month he sketched his first figure for a small poster of Amar Akbar Anthony. “I sketched Amitabh (Bachchan),” he says. “He was 3 feet tall.”

There were 6 artists at the studio who did the finishing, each of whom were known for their ability with specific aspects of what is now called Bollywood poster art: “such as a shade of green or blue applied to the villains face, or a psychedelic effect juxtaposed on a figure”. Fadte says he learnt from each of these finishing artists. The first movie banner that he finished entirely on his own was that of Tere Mere Beech Mein, Dada Kondke’s first Hindi film, in 1981. It was 2 and a half feet broad, and 20 feet long. “It stretched across Imperial Theatre.”

This was also the last thing Fadte painted at the studio. “I realized this art didn’t have much of a future,” he says. He had enrolled in a 5 year diploma course for the Fine Arts at L S Raheja college back then. One of his teachers, Shirish Midbawkar, owned a studio where he created smaller posters out of photographs. Fadte foresaw that only photographs would be used for film posters once technology made it feasible to do so. He felt he should pursue a career in portraiture instead. He can’t remember why he thought portraiture would not die out too. Maybe because portraiture had been around for so much longer than film poster art? He doesn’t have an answer. Fate did. A cruel one.

Fadte had started painting portraits when he was 16. In 1988 he graduated with a Master Of Fine Arts degree, with a specialization in portraiture, from the JJ School Of Arts—one of India’s finest art schools. Through the 1990s he became a fairly successful portrait artist. He would ask for as much as Rs 5000 as advance for every assignment. He had 10 such assignments in a month. He had employed three artists to work under him so he could meet deadlines.

Then, towards the end of the nineties, the assignments dried up. Apparently most people didn’t want their portraits painted anymore. “Maybe it was because photographs are so much quicker,” says Fadte. “Maybe because with the new technology it’s now possible to photoshop oneself into looking good – which earlier only a portrait could do? I don’t know.” He had to fire his assistants. “Things had become so bad that I wondered if I would ever be able be able to see Rs 1000 in one place again,” he says. Things got worse. He separated from his wife, who retained custody of their daughter. “I would drink from four in the evening, till I passed out,” says Fadte. “Whiskey or rum. That’s why I don’t drink whiskey or rum anymore. They bring back painful memories.”

In 1999 Fadte received a strange request from an old client. Studio Plus, a studio in Worli whom he had done portraits for before, commissioned him to paint boxes like old Bollywood posters – for a show that fashion designer Abu Jani was planning in London. A photograph of one of the boxes, uploaded by Fadte on Facebook, shows Hindi movie poster style paintings of actors Madhubala, Nutan and Raj Kapoor and Nargis alongside names of the movies they were in. Ironies escape Fadte mostly, or he refuses to recognize them. His life’s most crucial irony has been that the art that he thought would die came back to save him– albeit in a new avatar. These boxes signify a trend that was only picking up when Fadte was commissioned to paint them, but which has gone on to explode in the decade since: the kitschisization of Hindi films, and India. The viewing of our cultural history—that also comprises the work of all those artists at Visual Arts—though the campy lens of the West.

Fadte, is unaware of the term ‘kitschisization’. He’s aware of art (his favorite artist is American painter and illustrator Norman Rockwell, whose work was also categorized as kitsch by contemporaries) but hasn’t really analyzed his own to see where it fits in– as long as it does. All he understands is that this trend has enabled him to earn up to Rs 15,000 a month. This has paid for, among other things, his visits to the doctor, his laptop and his gin. The second assignment of this kind was to paint another set of boxes, similarly, for a student’s college project in the United States. A photograph of one of the boxes shows an image of Nargis Dutt from Mother India next to one of Rekha from Umrao Jaan. The name of the movie alongside these is Kaante, which neither of them have acted in. Fadte believes it is interesting to mix and match things. Like the mermaid in love with a New Yorker in Splash. Like the invisible man, wearing dark goggles and bandages, trying to be inconspicuous in the English village of Iping.

As the trend caught on more work followed. On the bulletin board, next to portraits of a middle class Maharashtrian woman seated on a wooden bench, a model wearing an Arab keffiyeh and a turbaned farmer smoking a chillum, there is a snapshot of a large signboard that Fadte was asked to paint by hair stylist Sapna Bhavnani for her new salon Mad-o-Wot, at Bandra, in 2004. The board has Hrithik Roshan from Krrish, Sanjay Dutt from Mission Kashmir and Vidya Balan from Parineeta.Then there is Bhavnani, who seems to have sauntered into the middle of all this as David Livingstone would, in knee-length boots, hoop earrings and a white sun hat. She allowed him to sign his name and write his phone number on the painting and this led to a ‘poster’ being commissioned by VJ Anusha Dandekar. Also on the board, the name of the movie on this poster reads “Mere Yaar Ki Shaadi” (my friend’s wedding)’. It has portraits of Dandekar and her friends, the bride and groom, drawn from campy movie references. The art that Fadte had learnt as an eleven year old has lost its former glory of spreading across the city, as a marker of grandeur and fascination. It has reinvented itself to fit in with a new idea of cool that everyone wants a piece of.

But Fadte isn’t complaining. He doesn’t know why some people want their faces on certain movie posters, in the place of certain movie stars. “They don’t tell me,” he says. “I don’t ask”. Some of his customers ask him to paint them as if satisfying a guilty urge, on condition of absolute confidentiality. A couple wanted themselves painted in place of Shahrukh Khan and Deepika Padukone on a poster like that of Om Shanti Om. The wife of one of the city’s leading industrialists got Fadte to paint her children’s room. Another prominent business family from Pune asked him to paint their patriarch on a poster like that of Mani Ratnam’s Guru. Fadte cannot name these clients, as he cannot name a new hep lifestyle brand that took on his services to paint their products—coffee mugs, hand bags, linen and toiletries—with Bollywood kitsch, before switching to a cheaper artist later. He is not allowed to sign his name on the paintings he does for most of his clients. “Dhanda ka usool hai (these are the rules of the trade),” says Fadte about this. “Customer bolta hai to sambhaalna padhta hai (If the customer asks for this we have to comply)”. Like the New Yorker in Splash who had to plunge in to the sea with his mermaid to try and find a world where they could be together, like the invisible man who had to die before we saw his body again, Fadte is trying to fit in, but it’s not always a happy story.

In 2007, however, Fadte came closest to showing his work as his predecessors used to. For a movie. In a movie. He was commissioned to do hoardings for Sudhir Mishra to shoot for Khoya Khoya Chand, a period film about the yesteryear Hindi film industry. “It felt nice,” is all Fadte says about watching his work, in a movie, on a television he had back then. “But I didn’t see the entire film.” He was not invited to the premiere. Asked whether such things bother him, Fadte remains characteristically noncommittal. He recalls a Facebook chat he had with Vilas Tonape, an old college mate with a studio at Lakeland, Florida, whose portraits have exhibited at Chicago, New York, LA and Ontario. “We spoke about how he’s really moved on in life, and I’m still in the same room I started out from,” says Fadte. “We laughed about that.”

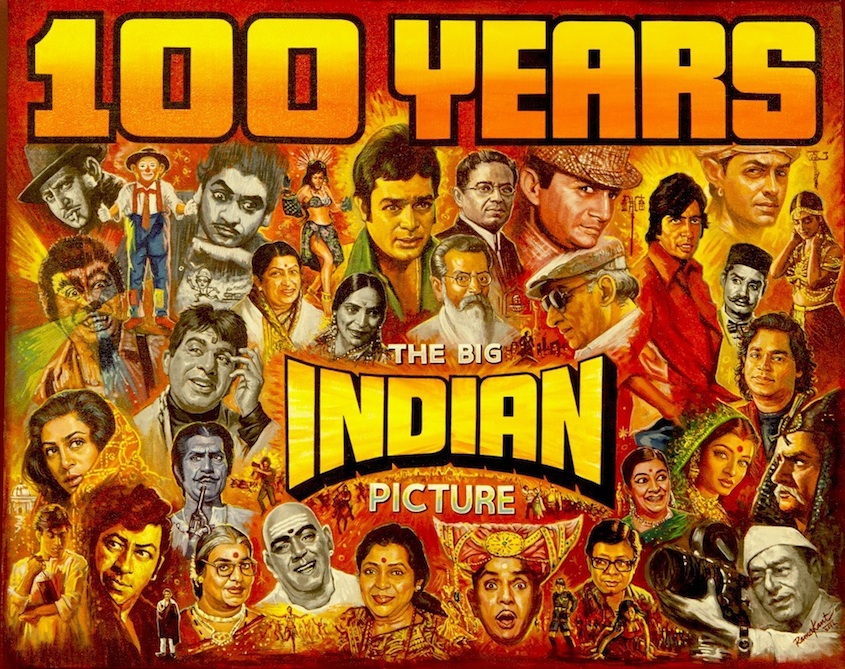

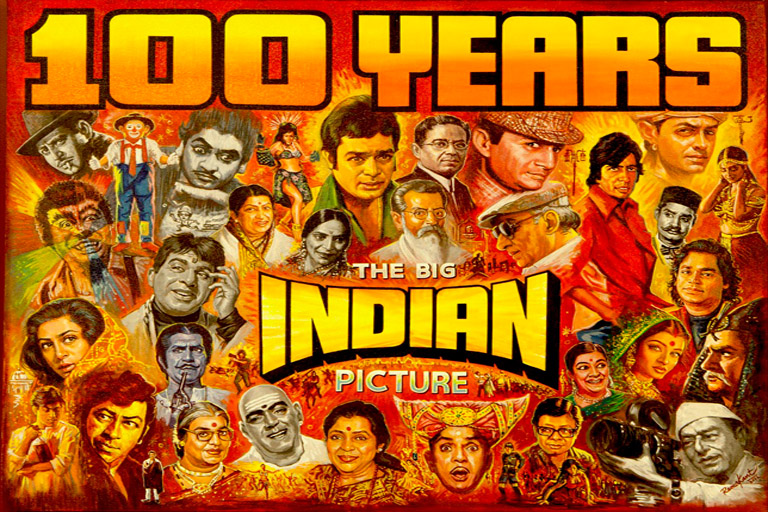

Fadte had drawn up a list of hundred names he wanted to feature in his 24 by 30 inch canvas for The Big Indian Picture: “I wanted to include the regional cinemas. Especially those from West Bengal, Kerala, Tamil Nadu. But I had to settle on 31 names because there was no space.” He feels particularly bad about having had to leave out “Rajnikanth, and important technicians of cinema”. But there is one person Fadte did fit in. He is a white-bearded man few will recognize. His name is Baburao Painter. Fadte remembers visiting his son’s studio in Kolhapur, when he was at art school. One of the reasons he chose to place him at the centre of the canvas is because he is one of the country’s earliest filmmakers. Also, Baburao Painter is India’s first known film poster artist.

A Portrait Of The Poster Artist As A Middle-Aged Man

SpecialsSeptember 2012

By Vidura Jang Bahadur

By Vidura Jang Bahadur

Vidura Jang Bahadur is a photographer. His projects seek to create a better understanding of individuals and communities by exploring the twin ideas of home and identity.

By Rishi Majumder

By Rishi Majumder

Rishi Majumder is Senior Editor at The Big Indian Picture.