“Life’s like a play; it’s not the length but the excellence of acting that matters.”

Sulabha Deshpande, 76, has been a founder member of the Marathi theatre groups ‘Rangayan’ (with theatre director Vijaya Mehta and her husband Arvind Deshpande) and ‘Awishkar’. Sulabha and Arvind Deshpande and playwright Vijay Tendulkar were also at the centre of the ‘Chhabildas Movement’ in Marathi experimental theatre during the 1960s and 70s. Her most memorable theatre performance has been that of Benare, the protagonist of Tendulkar’s landmark Marathi play Shantata! Court Chalu Ahe. She essayed the same role in its film adaptation. Deshpande went on to act in several other mainstream and parallel Marathi and Hindi movies, during the seventies and eighties, such as Shyam Benegal‘s Bhumika: The Role (1977) and Kondura (1978), Saeed Akhtar Mirza‘s Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyoon Aata Hai (1980) and Govind Nihalani’s Vijeta (1982), and Tezaab (1988), Ghar Ho To Aisa (1990) and Raja Ki Aayegi Baaraat (1997). Her last appearance in a Hindi film has been in English Vinglish (2012). Deshpande is soft spoken and she says her memory isn’t as sharp as it once was. Yet, as we go over the past at her Mahim flat, with the rain falling hard outside, she recounts the most amazing stories.

How did you begin acting?

My father (Vasant Rao Kamerkar) was a recordist with HMV. So, in a big hall at our home, we used to have rehearsals for songs and plays, which he would record. From when I was four years old, which is when I had begun to speak, I would enter that space and perform after the rehearsals. But my first ‘proper’ role was in school, in the seventh standard. There was a play written by a teacher in which I was cast as a small child. After this I did a play in my first year of college, for a festival.

Did you do only Marathi theatre, when you started out, or Hindi theatre as well?

Both. At first I worked in Marathi theatre. My first work in Hindi was Andha Yug, with (theatre director) Satyadev Dubey in 1964. That was for the theatre group Nandikar’s theatre festival in Calcutta. Four days before the play the actress who was playing Gandhari (a character from the Mahabharata, also in this play) left it, so P. L. Deshpande suggested my name to Dubey. That was the first time I met Dubey. He came to my house and said, ‘You have to do it in four days. You have to leave today.’ I said no at first, because my four year old son was ill. At that time Arvindji (Arvind Deshpande), my husband, used to work in experimental theatre too, which there’s no money in. This was reformist theatre, in a way. He said, ‘Go, because Nandikar’s is a very big festival in Calcutta and this team is representing Bombay and that too in Hindi.’ He would take leave from office to take care of our son. So, in four days, I prepared myself for the role of Gandhari. There was tremendous applause at the festival. After this I did two or three more Hindi plays with Dubey.

What was your first professional play— in Marathi or Hindi?

That was in Marathi: Shantata! Court Chalu Aahe. I had done work on two state level plays before this, but they were for amateur competitions. Even they happened quite late, because I was a teacher for 15 years in the Chhabildas Girls’ School, where I had studied as well. Incidentally, this was one of the reasons why our group was later able to get Chhabildas Hall, for 18 years, to rehearse our plays. That’s how our theatre movement came to be called the Chhabildas Theatre Movement.

Coming back, 1967 was when work began on Shantata… (Vijay) Tendulkarji’s play. It was supposed to contest in a government competition (the State Drama Competition, Maharashtra). It was an unusual play for its times, but it won an award for best play and I won one for my role as Benare, the central character. In about four months, appreciation flowed in from all over the country.

Shantata… has a story behind it. After Vijayaji (Vijaya Mehta) left the theatre group Rangayan because of her marriage, Arvindji eventually came to be in charge of it. He did two or three plays and this was the last one. He said to me, ‘There’s no money, in this field, but there is this government competition. We have good actors. Our writer is also good. So if we win a place in the competition, we will get award money and with that we can do more work.’ There were 77 people (in the group) in all, and their finances weren’t in a good state. Vijay (Tendulkar) wasn’t in a good state of mind then either. His elder brother was ill. But everyone insisted that he write and send in something, so he wrote the first act. There wasn’t much to it— no drama.

So in the 21-22 days the show was supposed to take place in, Tendulkar would write all night and Arun Kakde, who stayed next door to Tendulkar, in Vile Parle, would come in the morning, before the milkman arrived, to deliver bits of the script to Arvindji. Arvindji would work on these bits in the evening after his office hours, make notes, prepare them for the next day’s rehearsal. At night he would explain the characters to me. By the end of it I remembered everyone’s lines and knew all the characters. I wasn’t scared of doing the main role.

But what I found really challenging was that Benare, my character, doesn’t say anything throughout the play. She is not heard. She just sits there. In fact, in the final courtroom scene, the judge says: ‘You have 20 seconds. Say whatever you want to say.’ And even then, for twenty seconds, Benare says nothing. Yet Arvindji said that just one look would explain everything about Benare’s history and her life. It’s okay if she doesn’t speak, he said, she can speak with her mind.

Tendulkar, however, didn’t like that she didn’t say anything even at the end. So there was a big fight between them (Tendulkar and Arvind), because 21 days were nearly up and everything had to be ready. And, with two days left for the play to open, he had nearly finished the third act but still hadn’t given in the end. The way things stood then, the play would have had to end after Benare’s 20 seconds of silence. So, when Tendulkarji came to see the rehearsal, everyone shut him in the hall in which we were rehearsing in. Arvindji said, ‘Write the end and only then come out. Till then we’ll do the rehearsal outside.’ After half an hour, or 45 minutes, Tendulkar came out and gave it to him, and left without saying a word. We thought he was angry, but that wasn’t the case. The truth was his elder brother had passed away, and he was grieving. Even then he wrote it. In fact, I also knew the play really well by the date of performance because Tendulkar had explained everything to us as well, right down to the movements…

Shantata! Court Chalu Aahe went on to be translated into 13 languages. We made it in Hindi. And then someone took on the play for 100 shows. Then we did 150 shows. And then Rangayan shut down and a new theatre group called Awishkar was begun by us. I had suggested the name, in fact.

What was the first film you did?

Shantata… in Marathi. That was the first Marathi film. The second film was in Hindi. And that was Shantata… as well. They had taken a loan from NFDC. Dubey was to direct it. In the beginning I refused to do the main role because I felt the heroine had to look good. ‘Who told you that?’ Dubey said. I said, ‘I’ve seen it in so many films. Heroines are chosen this way. And you have taken a loan for this play. Me playing the lead would be okay for an experimental play but not for a film because you’ll have to pay this loan back. I’ll give you some names, they do good work, and they look good too.’ But both the names I gave him said they wouldn’t do it and Dubey was in a fix. So I agreed.

Govind Nihalani was cinematographer on Shantata… and you’ve worked on other films of his later on. With him as well as with Shyam Benegal. How did those roles come about?

Govind Nihalaniji was a part of Arvindji‘s and my circle. We were close friends. We were all at a party, once, at Juhu Hotel. Govindji, me and Amrish Puri were talking so that both of them were looking at me and I was facing the buffet table. Now, when the waiter came he put paraffin into the fire under one of the dishes on the buffet, to heat it, and it exploded into flames. My face and Govind’s back were burnt.

Govind had just arrived in Bombay then and didn’t have anyone in the city. So he stayed at our home for one and a half months, recovering. Shyam Benegal’s Kondura had started filming, at a village near Madras and Govind was a cameraman on it. He left for the site once his back was okay. I was avoiding work still. Though my face was mostly fine, my eyebrows had been burnt and I was uneasy about getting back on stage or screen.

Shyam phoned, asking me to come there. Govind said, ‘Come. You can just enjoy yourself with us.’ Once I reached there Shyam said, ‘Call the makeup man.’ When I asked why, he said: ‘Did I call you here to eat for free? I’ve called you for work.’ I said, ‘You know, you can see my face, how it is… ’ Shyam still insisted on getting my make up done, and immediately after took a picture and showed me. ‘Can you see any difference? No, right? I need Sulabha just as she really is. Come. Let’s start work.’ So that’s how I ended up acting in Kondura. Shyam later said he had really wanted a very natural look anyhow.

You directed a children’s film called Raja Rani Ko Chahiye Pasina.

I used to direct children’s plays. This was one of them that Tendulkarji had written. It was a Marathi educational play that was later translated into Hindi. So V. Shantaram saw the play and said, ‘I want to make a film based on this play. Will you do it?’ But I had never directed a film so I took a month or so first, to figure how to adapt it from theatre to film. It had to be like the play, but it couldn’t be exactly like it. So Tendulkarji and I reworked the script. The story is that the king and the queen don’t have any children. And someone says it’s only when you sweat that you’ll have a child. So they want to sweat and to be able to do so they travel, search for the answer… in the end they learn that without work it’s not possible to sweat…

We went to Shantaram’s office. It had huge doors and there was his famous cage(a golden cage with a parrot in it)outside the office. Shantaram looked at the script and said, ‘However you want to do it, go ahead.’ And on the first day, when we took the first shot, he was watching us from his office on the first floor. It was very sunny and he had this flat hat which he sent down to me. So I wore the hat and began work. Someone took a photo of me in that hat. Someone also said, ‘You are wearing V. Shantaram’s hat. You are making his picture. So now we need to salute you too.’

You have worked with Smita Patil in several movies. What are your memories of her as a co-actor or as a friend?

Smita wasn’t exceptionally beautiful but she was very attractive. She was seedhi saadhi (simple) and didn’t really bother about how to be stylish, how to dress. But she was a fantastic actress. Her parents were social workers and right from childhood she wanted to help whoever she could. Her mother had told me of an incident from when she was a nurse and Smita was four or five years old. Smita had heard about a woman in the hospital in which her mother worked, who had had a third daughter and so no one was coming to see her (because she had given birth to yet another daughter, instead of a son). So Smita’s mother had made tea and Smita kept a portion of it separately. Her mother asked whom she was keeping it for and Smita told her about the woman who had given birth to a third daughter. She was crying about this. So she went to visit the woman with her mother.

In Pet Pyar aur Paap, she was playing a garbage collector. On set there was a hut and the garbage that piled up outside it was very dirty. Smita put her hand in it and I said, ‘Don’t do that. There’s no place to wash your hands. You want to do your work well, fine, but don’t put your hand in dirt.’ She said, ‘Sulabha Tai, do you know where the director is standing? Right in the middle of a puddle, because that’s where the camera is. He’s going to take a shot of me. I shouldn’t be complaining.’

The last film I did with her was Bheegi Palken. After my last scene in the movie with her was done, as I was leaving, I noticed Smita searching for something frantically. She said, ‘I had kept my mangalsutra here and now I can’t find it.’ Her shot was ready and waiting so I gave her my mangalsutra, saying she could return it whenever we met next. But after this she fell ill. I went to see her in the hospital and I remember there was a bottle there (near her bed). I asked her for what it was and she said, ‘Cough medicine.’ I said, ‘But you don’t have cough.’ She said, ‘I don’t have a cough, but I’m not getting any sleep that’s why I’m taking it. It’s good if I can get some sleep.’ I remember saying, ‘It’s not good at all. You’re having a child. Don’t do this.’ I knew there were personal problems she was going through, even though she didn’t tell me herself. She used to drink a lot of the cough syrup, and then sleep. Then her son Prateik was born. He was only 10 days old when she passed away.

After she was gone, I got a phone call from her mother. She said, ‘Smita has left something for you— tied in a cloth. And on that she has written your name.’ I had forgotten about the mangalsutra by then and said, ‘There was nothing of mine with her.’ But she said, ‘Your name is written on it, so it must be something.’ She gave it to me, I opened it, and in the cloth was my mangalsutra.

Your last Hindi film role was in English-Vinglish. How did that come about? Also, your character was different from the typical mother-in-law that we see in the movies. Do you feel women are getting more interesting parts in mainstream Hindi cinema?

There are lots of different roles nowadays for women. Gauri (Shinde, the director) just said: ‘I have faith in you, and there should be one Marathi (actor) in this film (because the central family in the film was a Marathi family). It’s a small role.’ But there’s no such thing as a small role. She never told me what to do. She just told me about the role and the scene. Everyone likes this film, I feel, because everyone relates to it in some way. And true— I’m a different kind of mother-in-law in the movie.

What has been your most challenging film role so far?

I got a call from NFDC about a Kannada film where the director (Vasant Mokashi) wanted me for the main role. That was Gangavva Gangamayi. It won 16 awards. The character I played, the lead, was an old woman. I didn’t know one word of Kannada and I wasn’t comfortable. I said I couldn’t do it in the beginning. After four days the director came to my house. He said, ‘Please do it.’ I said, ‘How can I do it? I don’t even know the language, and you want me to do the main role.’ He said, ‘This story has been written by my father. It’s won an award. My mother said, ‘Give this role of Gangavva, to this Marathi actress that I’ve seen. She should do it.’ I don’t know why my mother said that and what work of yours she’s seen. But I’m doing this for her. How many days will you take to learn to speak the language?’ I told him it would take me two months, but first I would need the script and to find a lady who can speak both Marathi and Kannada.’ So they found a professor who knew Marathi and Kannada very well. The crew wrote my lines in Devanagari and they recorded them for me so I knew how to say them. I, on my part, worked hard at all of this for one and a half months. But I still didn’t have any confidence. I told them during the shoot, ‘Next to the camera, there must be a light cutter (a black sheet on a stand, to cut out excess light while shooting) with my lines and cues written in big letters. I won’t read it, but I need the confidence of knowing that that is there.’ They agreed to this.

I remember there was a big scene, where my character says something very angrily. While talking, I looked from left to right, and the camera was on a trolley. It was moving from a long to a close to an extreme long shot. After I had finished, the cutter had to be moved between shots. But while doing the next shot I realized that there was no cutter there. And so I got nervous and forgot my lines and began to speak in Hindi. And the people who were watching started laughing because they didn’t know that I was Maharashtrian. Whatever they had heard till then was in Kannada— so they thought I knew Kannada. Then the director made everyone get out and did a tight close up.

I had said to the director at first that I’d do it but they’d have to get a good artist to do the dub. So they had arranged for a big Kannada actress to do it. But then I tried to do the dubbing myself. After listening to it for one or two months they said, ‘Sulabhaji’s done very well. Her voice can be used.’

Now, I did another film and there was a Kannada actress working on that. And she said to me, ‘Haven’t you heard, a Maharashtrian actress has won an award for a Kannada film. I haven’t seen the film but the actress who played the role of Gangavva, she’s Maharashtrian. And still I got second place.’ She didn’t know I was the same actress.

Gufi Paintal, 70, is best known as the scheming Shakuni from B.R. Chopra’s lavish adaptation of the Mahabharata into a TV series. He was also casting director, associate director and production designer on the show. His portrayal of Shakuni was so popular that he appeared in Paisa Phenk Chunav Dekh, a satirical news show on Sahara Samay Rashtriya as the character, where he analyzed political trends. He played Shakuni again in 2011, in the TV serial Dwarkadheesh – Bhagwaan Shree Krishn for the now defunct channel Imagine TV. Prior to this he had essayed another villainous role, that of Britisher Charles Metcalfe, in the historical series Bahadur Shah Zafar on Doordarshan.

The brother of comedian Kanwarjit Paintal (often referred to and credited as just ‘Paintal’), Gufi has also done character roles in several Bollywood movies of the eighties and nineties, such as Kranti (1981), Dahleez (1986), Heer Ranjha (1992) among others. He now seems focused on direction. He has directed Shree Chaitanya Mahaprabhu a film on the 16th century saint by the same name and a Chhattisgarhi movie called Mahatari. The interview takes place in the living room of his Andheri flat, over cold drinks. There is a large fish tank next to us. Sunlight streams in. The sound of his cook bustling about in the kitchen merges with that of morning traffic. Gufi answers each question in a relaxed, yet brisk manner.

What was your journey into the movies like?

Paintal (Kanwarjit Paintal), my younger brother, the comedian and me were always working on little plays, among ourselves during our childhood. We used to enact small shadow plays based on what we saw in the movies, because my father was a veteran cameraman of his time, way back, in Lahore. So it was a fascination and we were always dreaming of getting into films. But in those days the rules were very different because the kids used to never select their own careers like they do today. My father, after I finished school, thought I should study engineering. So after graduating as an engineer I joined the Tatas in Jamshedpur, Bihar, when there was a defence emergency because of the China war. So I served with the army, from Bihar, for a few years, and then went back to working with the Tatas. I was transferred to the Tata Engineering & Locomotive branch here in Bombay from Jamshedpur. And by the time I had arrived my brother had already graduated from the Film Institute (Film and Television Institute of India or FTII). He had got his first break and had begun to establish himself. He knew of my fascination for films so he said, ‘Forget it, you’re just doing it (engineering) because dad wanted you to do it. So now, since I am here, you join my line only.’

While I am four years older than my brother he’s actually senior to me, in this line, by four years. He and Asrani had been accepted, in a big way, at that time by the industry and that was a big help. First I joined as an assistant director, at the age of 24. I was behind the camera. Then I began getting character roles. Then I joined as one of the technical heads in B.R. Films and I started looking after the ads division. I used to direct ads also for B.R. Films, under the banner of ‘B.R. Ads’. And then it so happened that we did Mahabharat and the rest is history.

You’ve said your most memorable role is that of Shakuni, in Mahabharat. How did you get the role?

I was the technical head, associate director, production designer and casting director of Mahabharata. So I selected actors after interviewing and auditioning about 3500 people. I would select three to four persons per character and then show it to my seniors, especially B.R. Chopra, Dr. Rahi Masoom (Raza, an Urdu poet) and Ravi Chopra. And we would sit together and decide who was the best one for a particular role. I also suggested people for Shakuni, but they had already me in mind. So it came on a silver platter. Actually I had played the villainous Britisher Charles Metcalfe for them, opposite Ashok Kumar in Bahadur Shah Zafar, a TV series on the last Mughal Emperor. They were impressed by that performance.

Is there any other role, that you enjoyed playing apart from Shakuni?

There is a role in Sauda that I enjoyed. That was the role of a patriot who was being hanged by Britishers. This man is being hanged, his mother comes to meet him in jail and he says, ‘See I’m perfectly alright, I’m not nervous.’ And she says, ‘Dekho, jab se tumko phasi mili hai, toh mera ghar nahin hai, mandir ban gaya. (See, since you have been condemned to hang, my house has become like a temple.)’ So I still remember that role. Then I remember Metcalfe’s role. There was a picture called Suhaag (1994) with Akshay Kumar and Ajay Devgan. I played Akshay’s uncle. I enjoyed that. And then I enjoyed Heer-Ranjha (1992). I was the villain— Kazi. And then most recently I’ve acted in a Punjabi film. I play the father, a sardar. Then there’s another film in Chhattisgarhi, Mahatari. Then there was one with Dharmendra— Maidan-e-Jung. I feel all my roles have had something to say.

What was it like to work with Mr. B.R. Chopra? What was he like as a person?

He was a very deep thinker and he would give a lot of importance to the screenplay and the story. Of course, dialogues and lyrics as well. He was a very well educated man, a double MA in his time and a renowned journalist. He started his career as a film critic in Lahore. And he was really ‘forward thinking’. He used to make pictures which were 20 years ahead of their time. All the films, if you take them, right from olden times… Sadhna was a film in which he wanted to say that even a prostitute has got a right to marry, or get settled. Then there was Ek hi Raasta, about widow remarriage. Then there was Nikaah, which was about talaq (divorce) by women. Insaf ka Tarazu was about a woman being raped, which is now a major issue, but which was made 30 years back. He used to always have something socially relevant to say.

What were some of the reactions to your role as Shakuni?

It was great. They used to hate me on television but they loved me otherwise. I still get invited to places as Shakuni mama, but they love me and they’ve given me a lot of respect and a lot of memories, so I’ve got no regret. In fact, a very big Hollywood actor said that good, bad or ugly, whatever role you get, every actor must get one role to be recognized with. So once he’s recognized, label lag jaata hai (the label will stick). People have got faith that you can give him any character, he’ll be able to perform. So that was one good thing that happened with Shakuni, that people started relying on me, thinking that I can do a good role and a bad role.

Did you face the risk of being stereotyped as a villain after playing Shakuni?

I am always experimenting. I do very, very different roles. I am not copying Shakuni at all. Apart from 20 years after Mahabharat when they called me for Shakuni (for the serial Dwarkadheesh) again, when I accepted. In between lots of people wanted me to do it but I used to say no, because I knew that I cannot surpass it (his performance as Shakuni in Mahabharat), so it was useless trying. This time because they really wanted me and because it had been a long while, I accepted. Also because it was a good production house— Sagar Films.

You have done a lot more of TV than mainstream Hindi films. I’ve seen a lot of other character actors working more in TV too. Is there a reason why TV is a preferred medium?

It’s just to vent your desire to act. At least you are busy. Also because you have to wait for films for a longer period before the films release. In this case you don’t have to wait and you’re being seen in a more regular way. And it pays well.

Is there a difference in the medium— how actors perform in TV and film?

Performance wise I would say no. But we actors tend to give our best to cinema and definitely there’s sustainability in films. I would say cinema is like a mother. TV will never be able to compete with it. TV can adopt cinema into its medium. You can see a movie on TV. But you cannot watch a TV serial on the big screen. Also actors now are freer to do little bit more of their stupidity—what they would like to call ‘acting’—on TV. But in cinema they are more controlled because that is only two hours and those two hours are being looked after by the director and his team. But in TV nowadays, once you give an actor a character, no one really bothers about what you’re doing. You’re just doing your job the way you think best. I’m also very disappointed because the directors very often change in the course of shooting a serial. In some cases they change in a matter of hours. So directors don’t always know what you’re doing, so whatever you’re doing is okay. That is not so in films. In films there is one captain— it’s he who sails or sinks the ship.

You’ve directed a film on Chaitanya Mahaprabhu…

Yes. Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. It was produced by people who made Abhimaan, Ambitabh’s (Bachchan) film. And we had very powerful actors like Sachin Khedekar, Madhu and Saheb Chatterjee from Calcutta who played the main lead. There was Sushmita Mukherjee also. The film was about the life of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, who was supposed to be a reincarnation of Lord Krishna. How he took birth, who he was, his journey. I can’t really call it a biopic because, like the Mahabharat, there are many versions of his story. So this is a fictionalized account, in a way.

I’ve also directed another one called Mahatari in Chattisgarhi, which is yet to be released. I’ve directed it with the local cast and local technical crew from Raipur. Also, I did a lot of assistant or associate directorial work with B.R. Films, from 1978 till 1997, when I resigned. Mostly during those years Mr. Ravi Chopra used to direct the films or TV serials. And some major films, when he was healthy, Mr. B.R. Chopra would.

Do you feel that character actors get due recognition from directors, or the audience?

Not in the way they used to. Because now if you throw a stone it’ll land on an actor somewhere. And it is very sad that today the scene has changed so much, because the casting directors and coordinators function in such a way that a 25 or 16 year old boy or girl is cast as a father or mother, or a 30 year old is cast as a grandfather— so it’s not authentic. In our times the heroes were a little too old, and they would still be playing college boys. But today it’s the reverse. Now the older characters are being done by youngsters.

Is there any incident from your shoots as a character actor that keeps coming back to you?

For my first film, a film called Dimple, I was playing a villain. I was shooting for it in December in Mahabaleshwar. It was Bhagyashree’s father’s film— Mr. Vijay Kumar Sanghvi, Prince of Sanghvi. Satish Kaul and Rita Badhuri were the hero and heroine. So I was supposed to be boating in the lake and it was freezing. It was foggy all over. I remember it must have been around four in the evening. I was supposed to be rowing the boat, with the heroine in it. After sometime the hero was supposed to come with his friend and his boat was supposed to ram my boat and he was to take the heroine into his boat and overturn mine.

Now I hadn’t told anyone I didn’t know swimming at that time. I was very young and was scared that I will be taken out of the film. This kind of fear is there sometimes, in new actors. So I didn’t mention this till he hit the boat and it overturned and I fell into the water and began shouting, ‘Help me, I’m going to die, I’m sinking.’ They thought I was acting while I was actually getting frozen. It was almost 4 or 5 degrees. Finally they thought, ‘Why isn’t he coming out?’ So people dived in and took me out of the water. I was half dead. And then they poured some brandy in my mouth and that’s how I survived. Then I told them, ‘I didn’t know yaar. I’m sorry. I was scared you would take me out of the film.’

Aanjjan Srivastav, 65, became a household name after he played Srinivas Wagle in the popular Doordarshan sitcom Wagle Ki Duniya, from 1988 to 1990. The show, based on characters created by noted cartoonist, R. K. Laxman and inspired from his ‘common man’ was rebooted in 1999 as Wagle Ki Nayi Duniya and once again, last year, as Detective Wagle. Srivastav also acted in several other TV shows, among them Tamas and Nukkad. In mainstream Bollywood, he has acted in movies like Hrishikesh Mukherjee‘s classic comedy Gol Maal (1979); Mr. India (1987), Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa(1994) and Chak De! India (2007). He also acted in Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay! (1988) and Mississippi Masala (1991).

However Srivastav is committed, till this day, to his first love—theatre. He is a longstanding member of IPTA (the Indian People’s Theatre Association) of which he is currently the Vice-President. Dedicated to his craft, Srivastav holds strong views on what really constitutes an actor. We are in his living room. His youngest daughter, a college student, darts in and out, bringing us refreshments, or simply listening in.

You had studied law and you were working in a bank before you got into acting full time. What was your journey into acting like?

I had never really thought about acting as a career. In my childhood I had started writing, imagining things… I visualized things and imagined, say, Dilip Kumar—in those days Dilip saab’s films were running—if Dilip saab was to play Yudishthir’s role (in the Mahabharata), then how would he do it? I’d come up with my own version of Yudishthir. In this way I would write a script.

The music composer Salil Chowdhury was my mama’s (uncle’s) friend and he used to come every Saturday in the evening with his wife and they used to talk about the IPTA theatre movement. We used to wonder what they were talking about. When we’d try to come close, to listen, the grownups would tell us to get out. Still, these ideas entered my subconscious.

But my dad wanted me to focus on my studies. I was not very interested in Maths, but he wanted me to do Maths. I managed to pass, but it was torture for me. During my higher secondary exams I met a teacher with the NCC (National Cadet Corps) who was making a film with Balraj Sahni in Calcutta, where I have been born and brought up.

I was in class 11 when I met Balrajji at the Technician’s Studio. It was then that I really understood what an ‘actor’ is like. I didn’t understand what being an actor entails, much, before that. In childhood I would sit with my mother, listening to the actor Shombhu Mitra’s radio plays and, while listening, I think, a culture of appreciating good acting developed within me. I don’t know exactly when or how that happened, but it did. I was very impressed by how he modulated his voice, which is especially important on the radio because people can’t see you.

So, now, in class 11, I decided to begin by doing some radio plays and began practising for this. Then I gave an audition and got selected. My voice was better then. It was softer, a more ‘romantic’ voice. I did a radio play called Lapata. Shombhu babu’s wife Tripti Mitra and a theatre director, Krishna Kumar, were performing in it with me. They advised me to do theatre and I said I would, but my dad would not allow me to go on stage. So I became very cynical. Then my mother said, ‘For now, do whatever he says. Get a job at a bank. After that do whatever you want to do.’

Still, I was very inspired in those days by actors like Motilal and Balraj Sahni. And then I read about them. Then when I saw Balraji’s background… He was an actor from theatre as well as a social worker. Balraj Sahni was one of the few actors whose films my father allowed the family to see.

Which actors and films did you watch growing up?

We got ‘licence’ to see Balraj Sahni, but we couldn’t see Shammi Kapoor because my father thought of him as a ‘hooligan’. Rajendra Kumar too we couldn’t see. Dilip Kumar— yes. And I saw Om Prakashji, and I understood from him what a great character actor was and his characters remain in my mind till date. As a result of these influences, even when I began acting, I never thought about whether I was playing a hero or another character. I never thought about doing a lead role or singing songs. Instead, I thought: If I am that character, then how will I feel? There was always a wish to do something new with acting.

And that’s why I felt that theatre was a place where I should ‘make myself’. I wanted to be one of the best actors on stage in Calcutta. Whatever I am today, is because of that background in Bengali theatre and then Hindi theatre. For 10 to 12 years in Calcutta I was doing plays. After that I came to Bombay. I had already done one film because I was already playing lead roles in leading theatre units— with Sangeet Kala Mandir Alakar, Anamika Kala Sangam… So naturally those who wanted a Hindi speaking actor, especially the Bengali directors, quickly chose me. Chamelee Memsaab was one such film, which had Mithun (Chakraborty) and Tom Alter. But I was not really mad after cinema, I was keen to follow after what Balrajji did instead. I had thought that when I went to Bombay I would join IPTA. And that’s what I did. From then till today I’m in IPTA. Since 1978.

You are Vice President at IPTA today. How did your association with it begin exactly, and what has it given you in all these years?

I’m also the treasurer for IPTA Mumbai. In 1968, after I got a job at Allahabad Bank, I was free to do anything. But since I wanted to go to Bombay, I needed to have a reason to be here, in case I didn’t get a job at the bank branch here. So I thought that I’d try and get a job in the bank but also study law— and that would be another reason for my being in Bombay. But the job worked out. So then, in the morning I would study law, in the afternoons I did my job, and then I did theatre in the evening. I went on to do theatre for a record 46 years— despite my father’s great distaste for it, I never left it.

I was lucky to get into IPTA and to learn there from theatre director and actor R. M. Singh— he would give us new entrants many lectures on acting. He mentored many important directors like M.S Sathyu. The IPTA inter collegiate (competition) used to have a R. M. Singh Trophy, for Best Direction. And he truly was one of the best directors, and a great coach. I remember being scared of him.

R. M. Singh opened the doors of IPTA for me and began giving us some work. He used to teach us how to act realistically and about the things an actor needs to pay attention to, like characterization. An actor should know not just acting, but lots of things— he should read, write… This isn’t nautanki (folk theatre). It’s a very serious job. You are giving something to society and you should be very serious about your job, about what you’re delivering, how you are delivering it, what impression it makes on the audience. That’s what the theatre is. You need to engage the audience. Acting isn’t only about delivering lines. It’s a kind of discipline.

Singh and M. S. Sathyu got me a part in a play called Bakri. It is political satire by Sarveshwar Dayal Saxena and M. S Sathyu turned it into a play. I played Mrs. (Indira) Gandhi in it. It was a super hit at that time.

Sathyu was the head of Bombay IPTA at the time and he was President of IPTA for all of India and he headed the ‘acting branch’ of IPTA as well. It was because of him that I went to Bombay initially. There were many people in IPTA, who aren’t well known. Another person who used to inspire me was A. K. Hangal. And also Balraj Sahni, naturally— my guru.

Your father, who was against you becoming an actor, finally changed his mind. Why?

He allowed my theatre after my uncle said, ‘Arrey baap re, Dharani Ghosh has praised Aanjjan! He has never praised anyone in theatre.’ Dharani Ghosh was a very tough critic, a very important journalist, in Calcutta. He used to write in The Statesman. Every group was so scared of him that they would only call Dharani after four or five shows. He used to trash plays and even very senior actors. He was very learned about theatre. He had said that Aanjjan and Suresh Sharma could do well. Then my dad said, ‘Ok, do theatre, but alongside your job.’ But after Wagle… he wrote to me here in Mumbai saying, ‘Your character should be your main goal and success should only be your stepping stone.’ It took me sometime to understand what he wrote. I understand it now.

Did you ever think of acting full time? When did you finally decide to quit your job?

I wasn’t able to make it a career for a while. When I started out there wasn’t any institute as such. NSD (the National School of Drama ) and FTII (the Film and Television Institute of India) had just begun. When I asked Dad about joining FTII he said, ‘We cannot afford it. Go work and whatever you’re doing, in terms of acting, already, keep doing that. I cannot afford to send you to FTII.’ So I worked. I kept gaining experience in theatre and film, slowly.

As a result, I was busy with my work and theatre and whenever a shoot was convenient I did it, but whenever it wasn’t— I didn’t. So I didn’t look at how I would make a career out of acting. My job was carrying on fine. My house was running. Money was not a big criteria to me, it was not really necessary beyond a point. It was only necessary that I didn’t ask my dad for money. As time passed, however, I realized that I needed to do better roles, charge more, because only then would people see my value.

Finally, at one point, I felt, I needed to leave the bank job. When I left, the bank people asked me not to leave. Even the chairman said to stay, though finally he said, ‘The one thing I ask is that, when you go for an interview for your profession, please mention Allahabad Bank.’

See, unlike Paresh (Rawal) or Anupam (Kher), who were doing films full time, I was into banking full time. After that I did theatre and after that film. But when I did Wagle, I became Wagle to everyone.

Also you had worked with Mr. Hrishikesh Mukherjee in Gol Maal, which was one of your first Hindi film roles. How did you get the role? What was he like, to work with?

Rishida was the first man whom I knew in Mumbai. Pallavi Mehta, who’s a Gujarati actress, and her husband J. K. Mehta, who was a director, were both with Miyan (theatre) group, in Calcutta, while I was in Adhakaar. When I came to Bombay, Pallavi said, ‘When you go there, write a letter to Rishida.’

When I met Rishida, both his films Alaap and Chupke Chupke had flopped. Before this, Rishida’s films hadn’t flopped as such, so he was disheartened, and he started making Gol Maal. He did it to continue supporting his staff. But I didn’t understand that the style of filmmaking was changing. While Gol Maal was happening, I went to Rishida’s house. I hadn’t got a job yet. I remember the first thing he had asked me was: ‘Have you eaten?’ I said, ‘No.’ ‘Give him some food,’ he had said.

This way Rishida gave me Gol Maal, then Bemisal, then Rang Birangi. He gave me work in Rang Birangi and paid me but that scene is cut so it was like a guest appearance ultimately. The scene had an actor being filmed during a shoot, when the police catch him. He told Raj Babbar to do the same role instead as at that time I wasn’t well known and he realized he needed an actor who everyone knew for the role.

But we kept seeing each other over the years. When I got married, one of the first places I went to was to Rishida’s house, with my wife. In his last years when he was in Lilavati (Hospital) I went to visit him.

Your role of Wagle had made you a household name. How did that come about?

I got the role because I had worked with Kundan Shah and Kundan Shah himself was pitching something to R. K Laxman. Doordarshan requested Laxman to do an adaptation of his cartoon (The Common Man). They said he could shoot the cartoon that’s in the book or animate it. But he didn’t want to do that. After two and a half years, he said, ‘On the basis of my cartoons, I will create some stories.’ He narrated some stories to them. Then Durga Khote produced these via her production house, Durga Khote Productions, which was one of the first ad production houses in India. Durga Khote’s daughter in law, Christina Khote, was Laxman’s friend, so she said, ‘Chalo, we’ll make it.’ Then he said, ‘Show me who are the best film directors?’ So that’s how he got Kundan Shah and Ravi Ojha. Laxman saw all the actors himself too. He called everyone and he would react outright to them.

Kundan had asked me to audition. I said to him, ‘Arre yaar, why do I need to give an exam?’ He said, ‘No, I myself am giving an exam, my friend. You are my test. Read for me. It’s a big cartoon, and so what if it’s a cartoon? They don’t want to do just a cartoon.’ So I read.

After one month, it was decided to let me do one episode. It was first called ‘Laxman’s World’ not Wagle’s World. So Mrs. Khote and Laxman sat at her residence. They took out the Times of India and started comparing me to the character. In the evening they were discussing it and Kundan went there and they called Ajay Kagti, for the writing. They made the first episode. After that everybody appreciated me— but not Laxman. He said, ‘No, he’s up to 90%, but he’s not 100%.’ He was quite a critic and he had conceived an idea of Wagle that was exceptional. He had thought of 6 episodes to begin with and 13 episodes later. The impression was so strong. I just entered into character and played the role in a realistic way, which he liked. Humour doesn’t require caricature. If you portray real life then humour emerges from situations. Life is like a taunt. There is humour in everything. So, after a few episodes, Laxman said, ‘Aanjjan is the barometer of this serial but Kundan needs to change.’ He always balanced the serial in his own way. Kundan also said he’s learned lot of things from Mr. Laxman.

At the government awards created for the TV Industry (the DD Awards), in the first year of Wagle…, we won it for Best Actor and we were nominated for Best Comedy. In the latter years, we kept getting it for Best Comedy only. We were angry. ‘Why do they only give us an award for comedy?’ I asked Laxman, ‘Am I just a comedian?’ He said, ‘No you are very good actor. Go and say what you want when your time comes to speak.’ So I went up on stage and said, ‘An actor is a humourist, a tragedian and a comedian. Why have I only been categorised in comedy? I’m an actor, I portray a character called Wagle who is a complete character. Humour came out of the writings and the situations. For the first time, I feel convinced, inspite of the three judges sitting here, that a comedian is a greater actor than a normal actor.’ The judges were annoyed with me.

Do you feel character actors get due recognition for their work today?

There was a time when character actors were respected. Especially when television came, the character actors were the most sought after. People in the film industry would look down on TV in those days. But some actors like Satish Shah and Shafi Inamdar would be cast in some cinema, even in cameos, because the directors felt that they had a greater draw and recognizability than even some film stars.

But nowadays… I was talking to a big actor, at a Lions Club meeting, and he said, ‘See we have been in this line for 30-35 years. But today people become stars overnight. After some days we see that star actor make a guest appearance in serials. And after some days, consequently, this has a positive influence on their cinema too (in the film’s earnings).’ Television does that. And TV also pays them huge amounts. And, smaller character actors, who are in television, they give them trouble instead. Those character actors who give you a result, because of whom serials have been running well for over a year, are not taken care of. But then who is the loser? That’s why you don’t find good actors nowadays for TV. The creativity suffers.

Rohini Hattangadi, 62 shot to fame with her portrayal of Kasturba Gandhi in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi for which she won a BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role in 1982.

She has acted in several films in parallel cinema, working with directors such as Govind Nihalani (Party, Aghat ) Mahesh Bhatt (Arth, Saaransh ) and Saeed Akhtar Mirza (Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastaan, Mohan Joshi Hazir Ho, Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyoon Aata Hai). She has won a National Award for Best Supporting Actress for Party.

The acclaim for her performance in Gandhi, however, had an undesirable side effect. She was constantly offered the role of the hero’s mother in several mainstream Bollywood films during the eighties and nineties. Among the most noteworthy of these performances is Suhasini Chauhan, Vijay Deenanath Chauhan’s mother in Agneepath. Hattangadi was 39 at the time, nine years younger than Amitabh Bachchan.

Aside from her work in films, Hattangadi has enjoyed a prolific theatre career. She and her husband Jaidev, a theatre director, began their careers at the Marathi theatre group Awishkar and went on to found Kalashray, a theatre group and centre for research, education in arts and talent encouragement in Mumbai. In 2004, she won the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for her contribution to Indian theatre. Today, she continues to act across film, theatre and TV. This interview takes place at her house in Bandra.

What’s it like to be an ‘character actress’ in Bollywood, where there has been a limited scope for the kinds of roles women can play. For instance, in many films, one sees female characters only as the heroine, the vamp or the mother…

I entered mainstream Hindi cinema playing a mother because of Gandhi. I was some 27-28 years old, so it was quite late to be a heroine, maybe, and run around trees. So I was stamped with the mother’s roles or supporting roles. It was very rarely that I got to do the main character in a film. In parallel cinema I have done main characters but in commercial cinema it was very difficult to have a heroine’s role. Only once, for Saaransh I was nominated (for a Filmfare Award) in the category of ‘Best Actor, Female’ but I didn’t win. The term ‘heroine’ is associated with younger characters and I never did such roles. And my experience with getting a role is that while sometimes directors are adventurous, the producers never are. They are not willing to take a risk. Once they’ve slotted you in a category you stay there. So I never got out of the ‘mother’ slot, whatever the reason may be. So in between I began saying: ‘Please give me a negative mother!’

Also, my characters rarely had a husband present in the film. And when the husband’s character was there, my character was not very strong. Since I was portraying strong characters well I was mostly cast as a widow who had single handedly raised her sons and daughters. And then, a few times, I got to do negative characters or comic characters. Like, with Pukar, it was a comic character, an interesting character. Then in Lajja, though the character was very small, it had grey shades.

So that was it. They don’t want to take risks. And these people have not spared any actor. For that matter, even Amitabh Bachchan was slotted as the angry young man. Then he was the angry old man too. It was only very recently that he started venturing into different characters. Like his role in Black. Even Amjad Khan, after playing Gabbar Singh, was mostly a Gabbar Singh. Amrish Puri was almost always the villain.

The parallel cinema at least had a greater variety in female roles.

Yes, yes, it did, it did. I’ve done a lot of parallel cinema also, like Party. Party was a film that revolved around one evening and the characters— they are brought out very well. As the evening goes on you get to know more about those characters. My character is a has-been theatre actor and she has crossed 30, so she’s not a heroine anymore. She has left acting for the love for her spouse, who’s a writer and she’s with him. And now she is finding that he has lost interest in her. So she’s like, ‘What do I do now?’ She gets to know about the whole falsity of the relationship and she’s staying in that.

Another such film was Arth. Where you had a role as the maid.

Arth was towards the beginning, immediately after Gandhi. I never knew who Mahesh Bhatt was, or anything about the Hindi film industry. Only Kiran Vairale I knew from theatre and she said, ‘Mahesh is looking for you and I will give you his address and you should go and meet him.’ Shabana (Azmi) sent me a message: ‘Don’t say no to him, it’s a good role.’ So I went and met him and it was the maid’s role which I think I liked actually. I liked the whole soul of that character because— they are so near to our lives, such characters. I remember my maid when I was a child. She was not formally educated. Her daughter was two years younger to me, she was studying in the same school as mine. So my mother used to keep my clothes, my school books, my uniformsthat I had outgrown. She used to keep those and pass them to her. Then afterwards I came to know, when I left Pune for the National School of Drama (NSD), that my maid’s daughter, she went on to do the Montessori course and she was teaching in Montessori. So she had achieved something being a maid’s daughter. So I had that in mind. And when I got to do this role, I immediately related to that.

How did your character see the central relationships in Arth— the love triangle between the characters of Kulbhushan Kharbanda (the husband), Shabana Azmi (the wife) and Smita Patil?

She’s relating to her madam. She’s a silent spectator of the agony she’s going through. That’s why I like that one scene where I’m sent to give the keys to Smita. And that was I think the interval scene and I suddenly turn and tell her: ‘Aree roti chin lo, khana chin lo, mard kayko chinti? (Steal roti, steal food, but why steal someone’s man?)’ That was maybe society’s reaction and also a result of not knowing what the ‘other woman’ is going through. And that plays on her mind ultimately.

How did you begin acting?

Right from my childhood, in Pune. My mother was very fond of sending me for dance classes, on an amateur level. My guru Surendra Wadgaonkar was a kathakali dancer and his wife was a bharatnatyam dancer. So we learnt bharatnatyam and katahakali. Whenever somebody used to call, ‘Rohini dance karti ho na? Chalo aake naachke dikhao.’ (Rohini dances right? Come on show us how you dance), I used to get up and start dancing. I was in school then, in the 5th or 7th standard maybe. Then, because of my dancing, I got a role in a children’s play which our teacher was doing out of school when I was in the 8th standard. I had 3 dances and a character to play: the character of a prince’s friend. So that’s how I got into acting.

Also my father, Anant Oak, was an actor and theatre director himself. He had worked in Bombay theatre with Vijaya Mehta in 1955 and with Arvind Deshpande. But his involvement came much later. I had started doing theatre during the vacations. And I liked it— when I would to go on stage and render dialogues and when the children, the audience would react to it. So afterwards, when my father was doing a play for state competitions, and he was not getting an actor for a particular character, my mother pestered him to try me out.

Ultimately I did that role and things went well from there. I eventually won the regional silver medal for best actress. And that’s how I started doing theatre seriously, because of my father. He was my first guru, you can say, into theatre. He initiated me into parallel theatre. Commercial theatre came afterwards. I went to NSD in 1971.

And how did you decide to do films?

When I was back from NSD, I started doing commercial theatre in Marathi. Filmmakers were just beginning to explore a different kind of cinema at that time. At the same time Naseer (Naseeruddin Shah), who was one year senior to me, had graduated before me from NSD, went to FTII and then was in Bombay working with Saeed Mirza, his batchmate. So when Saeed Mirza was making his first film (Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastan), he got to know of me as an actor from NSD. So he asked me whether I could act in it. And I said ok. And then we did a second film, which was Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyoon Aata Hai. And then I went on to do Chakra. At that time I was doing theatre and films together. And then I got Gandhi. So my fourth film was Gandhi.

Which do you prefer— films or theatre?

Well my first love is theatre. And I love theatre because you’re constantly exploring the medium. Even if your script is the same you perform in front of different audiences, in different places, your mindset is different every day, you have to cope up with it also and it’s a live medium and you have to create a universe in a 40 x 40 space. That is so exciting and that’s why you constantly experiment and why theatre experiments so much. It experiments on scripting, on the style of plays, even the sets are so different. Sometimes the box set is there and sometimes only a lamp can, as if by magic, recreate the living room. So it is constantly changing. And while performing I get the insights of different people because you get to portray so many different characters.

How did you get your role in Gandhi?

It was out of the blue. Dolly Thakore was assisting Sir Richard Attenborough in meeting all the actors and actresses in Bombay. One fine day when I returned home after touring with my play I found a note, that Jaidev (Theatre person Jaidev Hattangadi, her husband) had left for me saying not to keep any work as we have to go and meet Sir Richard.

Jaidev was well read, well informed and I was completely the opposite. He had said, ‘Rohini, there is a film being made on Gandhi and Dolly called us to meet Sir Richard Attenborough. You’ve seen The Great Escape? He was in it.’

Then we met him and chatted for an hour or so over a cup of tea. And the next day I got a telegram from Dolly—I didn’t have a phone then—saying I should call her urgently. So I did and she said I would have to go for a screen test to England. And at that time my play was running so we hardly had two consecutive days free. So I said, ‘Mera play hai, yeh kaisa ho sakta hai? (My play is there, how can I do this?) I can’t go.’ Dolly said, ‘Rohini are you mad? Please go.’

And then I went to Kamala Kassara whose play I was acting in and he said he’d manage till I returned, but that I’d have to be back in a week.

At England, they gave us one scene, the cleaning the latrine scene, where Baa (Kasturba Gandhi) refuses to do it. And then I was made to act with Ben Kingsley because they had determined three pairs of six people whom they would decide from. They had screen tested and paired us themselves— me with Ben Kingsley, Smita Patil with Naseeruddin Shah and Bhakti Barve with John Hurt. They did screen tests for two to three days. I did my screen test and saw it when I was there and I was very unhappy with it. Still when I was back Dolly told me, ‘Rohini, they’ve said to cut down on your weight.’ I asked why. So she said, ‘Richard has asked you to cut down on your weight because you have to portray a character from the age of 27 to 74. So they want to see you really patla (thin).’ So the rest is history.

It was a big production and one of the first few international ‘crossover films’. What was that experience like?

Actually when I was selected for Kasturba I didn’t know Mahatma Gandhi’s life very well. So first thing I did was stop at Mani Bhavan and buy (The Story of) My Experiments with Truth and his autobiography.

The vastness and magnitude of the whole project didn’t dawn on me till I started shooting for it. When I started working on it, after they gave us the script, was when I began to understand— till then it was just another character. My theatre background helped hugely because in theatre you have to be very disciplined. If I had worked here, in Bollywood, first, it might have been a real problem but because of the theatre background, the discipline the role required came naturally.

They had called me on the 1st of November, whereas we were going on sets on the 30th of November. So I had one month to do two things to prepare the role. One was spinning, using the charkha, and the other was improving my English, because, I was from a Marathi medium school, in Pune. So I had to undergo elocution lessons.

Meanwhile Ben Kingsley was also taking the charkha lessons and he was doing yoga. And then we had to work on the script as well and research it well because there were so many different incidents which were clubbed together in a sequence of scenes. So we had to find out which year a certain incident was, what the age of the character was in that year was and, consequently, how things should appear in a scene. The makeup man, hairdresser and I worked that out together for my scenes. Because there had to be a slow transformation from young to old, to 74 years.

The whole thing began at the end of November and then I realized how organized it was when for my first shoot I was 5 minutes late for makeup and I got a call. We were staying at the Ashok hotel in Delhi and they had taken some rooms there and set up make up department, costume department… So I got a call from the makeup department, on the hotel hotline saying, ‘Rohini, you’re 5 minutes late.’ So I would be 10 minutes early from then on.

When you won a BAFTA for Gandhi, what was that like?

Well, at the time I knew the character has gone down well. Richard liked it, everyone liked it. But I never imagined that I was going to be nominated, because I was not really aware of… You know, nowadays everybody’s aware of the Oscars, Cannes and the Berlinale. But at that time I was not aware of anything. Indo-British Films sponsored me to go to the award function. I was in England for a weekend. And that award function was also very different from what we used to have here. Filmfare was the most coveted award function in India, at that time, in the eighties. And I had written a piece also on that award function, on how different it was from what we had here at that time. First there were the nominations, and then one person getting the award, it came afterwards. They would announce all the actors and actresses. The nominees from each film were sitting on their respective tables. There was a Gandhi table, then a Tootsie table, an E.T. table. And then, whoever was nominated, for instance our writer was nominated, Sir Richard was nominated, Ben was nominated… so everybody’s name was there on the table.

Coming back to an entirely different experience, which is mainstream Bollywood. You played Amitabh Bachchan’s mother in Agneepath. I realize that you are younger than Mr. Amitabh Bachchan…

Yes. I’m younger to most of the actors whose mother I’ve played in the movies. Right from Jeetendra to Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan, Vinod Khanna… Only Raj Babbar, whose mother I also played, is younger to me by one year maybe. And Naseer is my age, or maybe 1 year elder to me. So I’m really… On average all of my sons have been around 10 years older to me.

Agneepath, released in 1990, was a culmination of eighties Bollywood, the angry young man was in full swing. How did that role come about?

In between there was a patch when I said, ‘No! I’m not going to do mother’s roles.’ And my secretary was trying to pacify me: ‘Rohini, don’t behave like this, roles won’t come after this then.’ But I still said no to three or four films. I said, for instance, ‘No, I will not play Feroz Khan’s mother… ’

Then there was this film called Sultanat which I had said no to too. That was directed by Mukul Anand. So when Agneepath came, also directed by Mukul Anand, my secretary calmed me down. So I said, ‘Okay, it’s fine, I’ll do it.’ So Agneepath was one of those ‘okay’ kind of films. So I went to Mukul Anand and he narrated the story and all.

And I liked it because that was the first time I was hearing a story which had different characters which could all be remembered. Otherwise all Amitabh Bachchan films were: Amitabh, heroine and villain. And that’s all. There were no other characters whatsoever. Agneepath was the first time I could remember even the police commissioner, I could remember the sister’s character, I could remember Mithun’s character, even the Pathan, that policeman… each and every character was so well defined and yet in its place.

I had done Shahenshah before that with Amitji. So in Shahenshah I could see him having fun on sets. Once I asked him on the Agneepath set, ‘What do you expect from this? I can see a totally different approach to the character.’ So he said, ‘The thing is Rohiniji Shahenshah was a fun film so it warranted a different approach. Here I want people to just sit, slightly alert, on the seat, not leaning back. Just lean forward and look at the film.’ So he’s that kind of a person and that explains the way he’s handling his characters now too. But at that time the the roles he was getting, like in Jaadugar and Toofan, made me wonder what he was doing, despite being such a good actor. But that’s Bollywood.

Have you seen the remake of Agneepath? What did you think?

Yes. Amitji’s Vijay Dinanath Chauhan in Agneepath was a totally different interpretation, altogether larger than life. And that time, that was the need of the hour. Hrithik Roshan treated Vijay not as a Don but as someone trying to be human, a middle class common man who is trying to fight it out. That’s what I felt. But, that said, the portrayal of all the characters was not coherent in the second Agneepath. I found (Sanjay) Dutt’s character to be larger than life, for instance. If it would have been on the same page that would have been a marvelous attempt. But because it was not it seemed odd. For that matter, Rishi Kapoor’s character was down to earth and real. But somewhere Sanjay Dutt’s character wasn’t fitting in. Also in our version, the first one, the characters of the mother and sister were utilized. The mother’s character had a motivation— that she wanted the son to transform, become ‘good’. Here the mother’s character wasn’t fully developed.

What are you working on right now?

My Marathi serial. I’ve shot a Telegu film. Then Jagdamba, a play I’m trying to revive. The play is on Kasturba only.

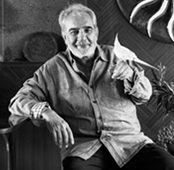

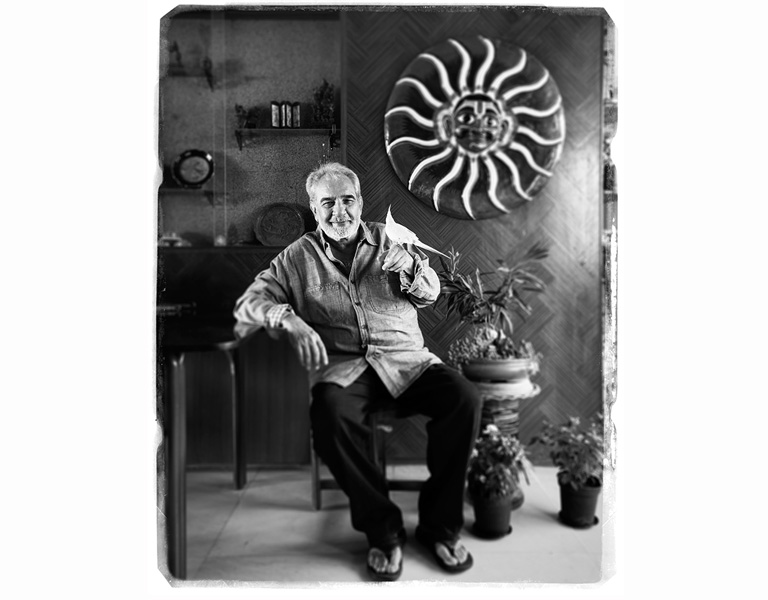

Kulbhushan Kharbanda, 69 is probably most recognizable to regular moviegoers as the villain Shakaal in Ramesh Sippy’s multi-starrer Shaan (1980). He has also done character roles in several other blockbusters of the eighties, nineties and 2000s such as Silsila (1981), Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985), Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar (1992), Hera Pheri (2000). He has balanced these with powerful, nuanced performances in parallel cinema, from early on in his career with roles in films such as Manthan (1976), Bhumika: The Role (1977), Arth (1982). More recently, he has been a part of internationally acclaimed films such as Lagaan (2001), Monsoon Wedding (2001) and Deepa Mehta’s Elements Trilogy (Fire, Water and Earth). His prolific career, which also includes roles in Punjabi movies, was brought to an abrupt pause in 2011 when he was seriously injured after falling off a horse while filming. The accident could not limit his work for long. Kharbanda worked his limp and use of the cane into the role he essayed in his comeback film Midnight’s Children (2012), Deepa Mehta’s adaptation of Salman Rushdie’s iconic novel.

Last year he came back to the stage as well, after 18 years, as the protagonist Rajadhyaksha in the Hindi adaptation of Mahesh Elkunchwar’s Marathi play Atmakatha. An avid traveller, Kharbanda was watching the Travel and Living Channel before we sat down to chat. His pet parrot nips gently at each of our trousers before settling on his shoulder while we discuss his work. This is not a cause for concern. Shakaal had sharks.

You became famous in the mainstream with your role of Shakaal in Shaan; Could you share a few memories of working on that film?

I don’t have many, or maybe I don’t remember now. My involvement was very short really. I was working with Mr. Ramesh Sippy, who is so professional, so methodical, that we shot my portion in two to three continuous schedules and it was over. I was not involved from the very beginning, I came in towards the end. They left that portion of mine, I think, and shot the rest of the film. So I don’t have many anecdotes from that film.

Before you took on this role of Shakaal, you had done a lot of parallel cinema. How did this mainstream film come about?

For me it doesn’t matter. I was offered my first role by Shyam Benegal, so I kept on doing films with him and then through his films, these commercial people recognised me or they recognised a particular character. And Salim-Javed saw the film and they recommended me to Ramesh Sippy and that’s how it happened.

You had been quoted in an interview, saying that you wanted to make the character of Shakaal edgier, like what it might have been a Bond film. But that didn’t happen. Why?

When Rameshji and me were discussing the character, I was thinking about it in a particular way but he said, ‘Don’t be too edgy because in our cinema we understand a particular kind of character’. And I think what he said was correct. That a certain consistency, to make the characters recognizable, was required of our cinema at that time.

What did he mean by ‘edgy’?

Edgy would mean making it more colourful, creating a character which was unusual compared to the usual villain, to make it more subtle— to take the character ‘to the edge’, so to speak. He (Ramesh Sippy) said: ‘Look. We always believe in black and white. And our audience— they love it. So one should be consistent when it comes to a particular character.’ I think I must have mentioned somewhere. It was not a big thing. In the beginning I just… He was absolutely right. I agree with him.

Do you think the idea, that way, of what a villain is has changed in our cinema? There are shades of grey in our heroes too. Does that apply to our villains?

I should talk to you actually about this film I saw, where there was no villain, I think…

Which film?

My daughter keeps showing me them on DVDs. And among the recent ones I haven’t found villains…

Current Hindi films?

Yes, I haven’t seen any villain as such. Because I think films have become more daring now and more experimental.

Is there a film which holds a special place for you either personally or professionally or in terms of a breakthrough in craft?

When you’re doing a film, everything’s important but sometimes it happens that in a film you just sort of come to know which kind of film you’re working in. You know what’s in the director’s mind. You know that people will say: ‘Oh, that film you did— it’s the same thing, nothing different.’ And you then feel it’s very easy.

But sometimes, if the director is serious, he makes you serious, and then different things come out all together. Most of the directors now, I believe, are more serious about their work. They don’t quote another scene, or another film, for you to imitate. There’s none of that.

For example?

For the last two years I’m totally out of touch because I met with a very bad accident. I had three operations and I’m still recuperating and I’ve done only four or five films since then.

You’ve done Deepa Mehta’s Midnight’s Children

That was just after my accident. A stick was given to me to walk.

That was worked into the script…

Yes, when I said, ‘I won’t be able to make it,’ she (Deepa Mehta) said, ‘We’ll give a stick, you’ll have to come.’ They were shooting in Sri Lanka. I went twice.

Did you read the book before shooting?

I had read the book long back. They keep sending scripts, those people. Sometimes you get tired, because they send every little change in script to you— yellow pages, red pages, green pages. It could be the 10th version, or the 11th version…

You’ve worked a lot with Ms. Mehta. You’ve done both parallel and mainstream cinema, you’ve done international films. How do they compare?

Well, when you’re working with Shyam Benegal, he goes into a lot of details.

Was he as detailed as the team of Midnight’s Children with his scripts?

No. He gave you a final script and everything would be there, but we would talk a lot.

Discuss the character?

This not with him only. Now the youngsters are coming up with a lot of new ideas that they really want to work on and I’m not sure if the industry will be changed or not, but if it changes it will be for the better, it will be more professional.

Do you have any younger directors that you want to work with? Or is it that because of your health…

No. My health is absolutely fine but because of the accident I had, word is out that I am unwell.

So you are fit and ready to…

Yes, I’ve done four to five films. I’ve done a German film.

Which one was that?

Junction Point. It’s an English name, but the German name is something else (Fernes Land).

And the director of that is?

It’s a Jung’s Production. It’s a German-French production, The French director is of Indian origin. I’d done some shoots after the accident. So those people are approaching me, but there’s not much from this industry. I think that it’s because the word is around that I’m not well. I don’t know how to tell people: ‘Look I’m alright.’ How to project… (that I’m healthy).

One of your earlier roles was in Mahesh Bhatt’s Arth. What was it like working on that film? What kind of conversations did you and Mr. Bhatt have on the character…

Nothing much. He said basic things. I knew Mahesh very well by that time. It’s a simple story. There are three people. They’re nice people. Nobody’s wrong but it happens in life. So a situation arises (an extramarital affair, a love triangle) and where could the situation lead? We started thinking about it from there— till the interval. We didn’t know where to take the film after that. I think this is a very difficult subject, that it’s difficult to justify all the three people. They were each justified but they were each sandwiched by the situation they were in. But then later on the easy way out was taken, because it was made from the wife’s point of view.

So that’s how the story was shot. Though I feel it was very easy to make it from the wife’s point of view because, in my opinion, the wife is already accepted by society. Society’s already sympathetic towards her. But I think the challenge would have been if you made it from the point of view of the mistress wouldn’t it?

Or the husband.

Yes, but well I’m not mentioning my name (laughs).

Another film that you did was Yash Chopra’s Sisila

Sisila was a small role.

But it was an important role because your role does bring the major conflict into that dynamic. It pushes things forward. But taking off from what you said, nowadays if you talk to actors a lot of them ask about the screen time they’re getting. Was that important for you?

No, because by that time I had done a film with Yash Chopra, which I think nobody knows about. It was Nakhuda. It was Yash Chopra’s production, directed by his chief assistant, I think (Dilip Naik). While making that he said, ‘Do this also.’ When I was going to a film festival, he said, ‘Live on my expenses there only.’ That’s how I did the role.

What was the experience of working on Lagaan?

With Lagaan, again, Ashutosh (Gowariker— the director) is very serious. He’ll come to your place, sit with you and discuss not once or twice but thrice or four times whatever he wants. At Aamir’s place, there were many readings before the film started. The whole script was read many times. Not me, because I was playing a king, but other actors were living like the villagers, they started really living in the village, most of them, before and during the film— to get into character. I saw this kind of rigour last when we made Manthan with Shyam Benegal. Those were the days when I last remember us doing things like that.

Before you had joined films you were a theatre actor. Which medium do you prefer? Also how do you think theatre shaped you as an actor?

In theatre you have to do your job and theatre is very particular about that. There can be no nakhra (airs) in that. The day of the show you have to be there, whatever happens. Because theatre has a kind of inbuilt discipline where you are not being forced to follow the discipline. I think every profession has a different kind of discipline. But I’m just using big words, making it a big thing. Why is that necessary? It is basically my hobby. I love theatre, I used to do it and still, you won’t believe, just now, I did one play (Atmakatha) after 20 years.

Yes, it was your return to stage.

Because while I was sick, I thought this is the best thing and that I must go back and test my reflexes again, and my memory. For 70% of the play I am talking. We’ve done shows in Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi and Jaipur. It was a good test for me. The ultimate test is theatre.

Interviews by Alyssa Lobo. Portraits by Nishant Shukla.

‘The rest is history.’

SpecialDecember 2013

By Alyssa Lobo

By Alyssa Lobo

Alyssa Lobo is Junior Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture.

By Nishant Shukla

By Nishant Shukla

Nishant Shukla is a mumbai based visual artist. He pursued a master's degree in Photography at the University of West London. His personal work has been exhibited at Fresh Faced and Wild Eyed, 2009 at The Photographers’ Gallery London, Photomonth 2010, Watermans Gallery and the PM Gallery in London. He has also showed his work at the United Art Fair in New Delhi. Nishant currently balances his time between photographic commissions and video work.