A profile of Guddu Rangila, one of Bhojpuri cinema’s most popular stars, known particularly for the offensive and lewd songs he sings.

On March 28, 2013, as the country was immersed in Holi celebrations, 35 year old Santosh Kumar was shot dead in Devsadih, a village in Bihar’s Sheikhpura district. He died for what may seem like a very strange reason. Kumar protested the playing of lewd Bhojpuri songs during the festivities. As revelers around him drank bhang, splashed colour on one another and danced to music blaring from loudspeakers, Kumar found himself in the middle of a brawl. 10 people were injured. And Kumar lost his life.

On the same day, just 250 kilometres away in the district of Sitamarhi a similar set of events occured. Reports don’t mention the names of the victims or assailants or even the exact location. Just that a man was shot dead. The reason? He had objected to the playing of profane Bhojpuri songs.

Also on the same day, Guddu Rangila released a music album named Chhokari Baaj Holi (A Holi for Womanizers). As expected, it was a smashing hit. Rangila, 38, one of the Bhojpuri music industry’s most well known voices, is famous, or infamous, for the obscene songs he writes and sings. Holi, the festival of colour, is known also to lend itself to a degree of sexual frivolity. Frivolity which appears to challenge, sometimes, ideas that lie at the heart of Indian traditions and society. For instance, some of the most ribald jokes cracked on the festival in the Hindi heartland revolve around the relationship between the devar (brother-in-law) and the bhabhi (sister-in-law).

But Rangila’s forte lies in taking what’s a spot of irreverent fun and pushing it, slyly, across the line that separates it from the disturbing. Last year’s Holi came close on the heels of the outrage that followed the tragic ‘Delhi Rape’ of December 16, 2012. So Rangila recorded for his album a song called Balatkar Hota Hai Rajau (Someone is being raped).

He shot a video too. In the beginning, Rangila is shown standing between two sari-clad women. He delivers a monologue, speaking about how incidents of rape have shot up in the country of late. He talks of love, consent and evil. He sings:

“Ehe haal dekh ke sabke aankh nam ba, sach to ehe ba ki aisan aadmi ke phansiyon ke saza bahut kam ba.

(Everyone‘s eyes are moist after seeing such atrocities/But the truth is that even death by hanging isn’t punishment enough for such people).”

Then, he gets to it. To describing a wife who’s alone at home because her husband is away. As she watches news of rape cases on TV, the maugi (housewife), says Rangila “Ke kuch kuch huwa ta aur ka kehlas ki (Gets aroused and you know what she says)?” He ruffles his hair, leans towards the woman on his left, smiles salaciously. The dholak, tabla and harmonium begin to play, signaling the impending arrival of a refrain you must listen for.

“Dekhat ho par TV ghare chhod ke biwi balatkaar hota hai aye Rajau. Arre uhe khati Holiya me Dewara ke haathe humaar hota aye rajau

(The wife’s watching TV, which broadcasts news of rape cases/And she says that during Holi, my brother-in-law does the same to me).”

The two women on either side of Rangila break into a kind of sedate twist, clapping their hands, wide grins on their faces.

There were widespread protests against the lyrics of Yo Yo Honey Singh after the Delhi Rape, to the point of a petition for the cancellation of his concert. But fewer people know, perhaps, of Guddu Rangila.

Rangila has been a Bhojpuri singer for over 16 years. He has recorded, he says, “more than 250 albums” and sung “more than 2000 songs”. He burst into the consciousness of the Bhojpuri music hearing public with his fifth album Ja Jhar Ke (What A Swagger) in 1999. His most successful albums since, Humra Hau Chaheen (I Want ‘That’), Jeans Dhila Kara (Loosen Your Jeans), Hum Lem (I Will Take) and, of course, Rasdaar Holi (A Saucy Holi) are brimming with sexual allegories that are even more vulgar than they sound. In case you think that isn’t possible here are a few examples. A ‘Mango Frooti’ (a popular processed mango pulp drink) in a Guddu Rangila song implies a pair of breasts, as do ‘lemons’. ‘Laal rasgulla’ (red rasgulla) is a euphemism for a vagina. ‘Maal’ (commodity), in Rangilaspeak is a girl and a pichkari (Spray) a penis and so on… Rangila’s popularity mushroomed over the years and in 2004 T-Series—a big Indian music company that has been a huge beneficiary of his rocketing album sales—christened him the ‘Diamond Star’. He is the only Bhojpuri singer to have been bestowed the title so far. He began singing as well as acting in Bhojpuri movies in 2006, and has since played the lead in five of them. His recently released film Ghayal Sher (Wounded Lion), saw him starring opposite Rani Chatterji, one of the highest rated actresses in the Bhojpuri film industry. Around five years ago, he founded his own company, Sanjivani Entertainment, that earns lakhs of rupees a month via both online and offline album sales as well as YouTube revenue.

***

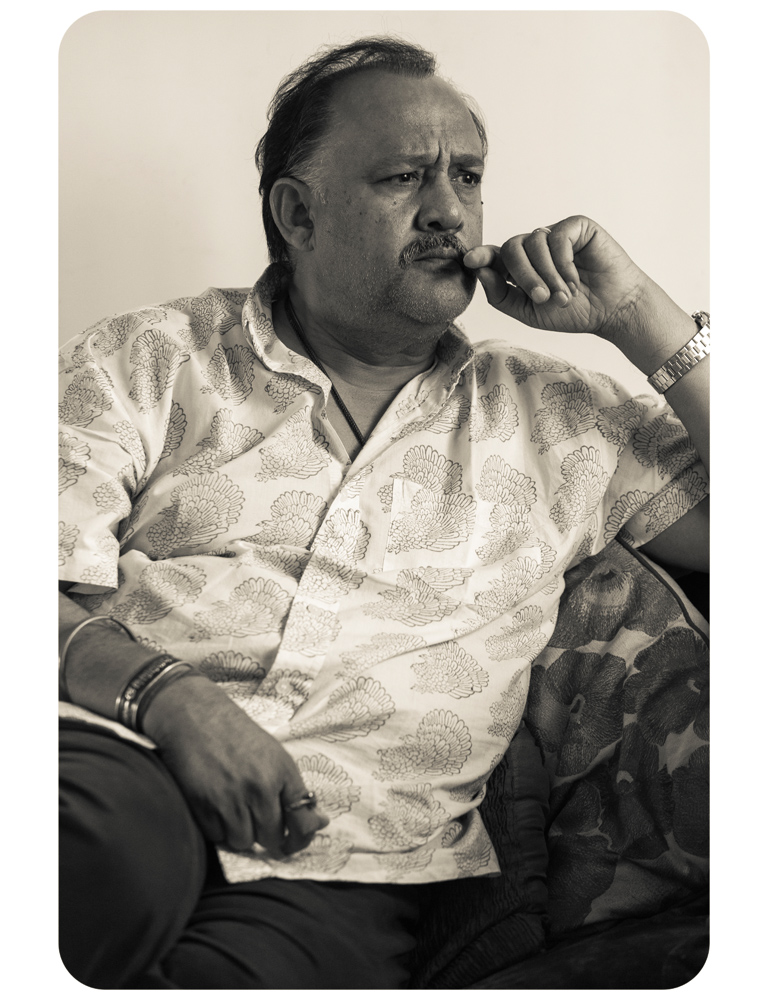

“I think I should wear a shirt.”

Rangila has unruly shoulder length hair and a rotund chubby face. He has just walked into the centre of the living room of a two-bedroom-hall-kitchen flat in Bhayandar, Mumbai, where he is putting up. He wears a grey vest and faded brown knee-length shorts. On his wrist is a red kalaava (a sacred Hindu thread) and a slim bracelet. There are a couple of astrological rings on his fingers. But the most striking thing about his appearance is a long fake pearl necklace that hangs from his neck, stopping just above his navel. The vest is tight for him, especially around his bulging stomach. It also reveals an immense amount of chest hair. Interestingly, he chose to walk in wearing just that and a pearl necklace and thought of a shirt only when he realized there was a photographer in the room.

He looks around the room, hoping for a reply. Besides the photographer and me there is also his assistant, but no one says anything. He disappears back inside the house.

His assistant stares blankly into space. He has shoulder length hair too, only freshly combed. “I am Mritunjaya Mastana,” he says, when I introduce myself. “I am Guddu Bhaiyya‘s (Bhaiyya means elder brother) manager, shishya (disciple), accountant and assistant.” Mastana accompanies Rangila to live shows. He opens for him with bhajans, or devotional songs. “I charge Rs. 10,000 for an hour,” says Mastana. He says Rangila charges Rs. 50,000 for an hour. He performs for about three hours at every show.

“Bhaiyya‘s live shows are something else,” Mastana continues. “People go mad. Someone’s head gets smashed, someone falls from the rooftop. The tickets range from Rs. 100 to Rs. 500.”

Rangila reappears wearing a dark blue shirt with the first two buttons left open. He settles on a black rexine sofa, opens a packet of Miraag khaini (chewing tobacco), pours and crushes some of its contents with his thumb and declares, to no one in particular, “I like eating readymade khaini.” He puts the tobacco in his mouth, dusts his hands and sinks deeper into the sofa.

On a small table to his right is a packet of Marlboro lights and a tall glass with crushed cigarette butts. Under it is a black motorcycle helmet. On its back are printed the words: “Hira Handa”.

This is Rangila’s world, one he carries with him wherever he goes. His wife and children live in Dwarka, in Delhi. But Rangila spends a lot of time outside the city, especially in Mumbai and Patna. Here, stuck on the wall of a rented apartment with uneven adhesive tape is a poster of his film Ghayal Sher. Rangila is at the centre, looking furious, blood dripping from his forehead, his fist raised. “Nayak, Diamond Star, Gayak Guddu Rangila (Actor, Diamond Star, Singer Guddu Rangila),” it reads on top. On the bottom: “Nirmatri: Deepa Yadav (Director: Deepa Yadav)” has been printed in small font.

On another wall are portraits of the Hindu gods Lakshmi and Ganesh and the Sikh guru Gobind Singh. A plaque, larger than any of these portraits, hangs next to them.

“Shree Guddu Rangila ji, Bhojpuri gaayak, Diamond star. Aapko yeh samman samaaj me utkrusht karyakon ke liye sanstha dwara sammanit kiya jaa raha hai (Shri Guddu Rangila ji, Bhojpuri Singer, Diamond Star. This respect has been accorded to you by the committee to honour you for your uplifting social work),” it reads.

On a tiny plastic stool in the room is a VCD Player with a few VCDs lying untidily on it. VCDs with videos of Ranglia’s own music albums—Lahanga Lutayil Holi Mein (She Was Robbed Of Her Skirt, On Holi), and Chhituaa Ke Didi, Tani Pyaar Kare De (Chhituaa’s Sister, Let Me Love You) as well as those of another Bhojpuri singer, Khesari Lal. What sticks out is the only non-Bhojpuri album in the lot: 50 Super Hit Songs of Kumar Sanu.

***

Before Guddu Rangila became ‘Diamond star’, before his risqué numbers began topping all the Bhojpuri music charts, his name was Sidheshwara Nand Giri. And Giri wanted to sing “soft romantic songs. Just like Kumar Sanu”. Sanu, from the state of West Bengal, neighbouring Bihar, was a leading Bollywood playback singer in the nineties, with innumerable hits and awards to his name. Incidentally, he too had changed his name— from Kedarnath Bhattacharya. He has since then faded into obscurity while Giri’s star continues to rise, even if not for “soft romantic songs”.

Giri was born in Chainpur, a hamlet in Bihar’s Siwan district. He went to a co-educational school where, “girls used to sit in the front and boys in the back”. Rangila remembers that only the students who did well in class by studying hard could talk to the girls, on the pretext of “exchanging notes”. Giri wasn’t one of them. “Nakal bhi akal se hota hai na (Even for cheating you need brains, right)? Everyone used to memorize the answers. I used to memorize the pages which contained the answers in the book I would cheat from,” he smiles. “I got decent marks from the first to the tenth grade— solely by cheating.”

Giri started to sing when he was 11. “I began by singing Ashtjaam songs, where you have to continuously sing ‘Hare Rama Hare Krishna’. And even in Ashtjaam, I used to sing like Kumar Sanu. What’s there in your mind is not easy to forget,” he says. “Then I began singing songs for Ram Leela and Shiv Leela (plays held during festivals celebrated in honour of the gods Ram and Shiv). So I slowly started getting offers for bhakti (devotional) songs.”

A few years later, Giri switched to singing kirtan (a genre of devotional songs), but this wasn’t his forte. “Kirtan isn’t just about singing songs. It requires you to act and do comedy. I saw I wasn’t able to do it properly, so I stopped singing kirtan,” he says. Then he sang nirgun gaan— monotheistic devotional Bhojpuri folk songs about one God who is formless. “But I saw I would be ‘medium’ (not very good) in nirgun gaan as well. So I stopped singing that too.”

Meanwhile, his father wasn’t happy he was wasting his time singing. “My father wanted me to become an SP (Superintendent of Police), DSP (District Superintendent of Police) or a (District) Collector.” So Giri enrolled in a college. But he finally left Chainpur for Delhi in 1993 at the age of 17. He wanted to be a Bhojpuri singer who sang for T-Series.

“At that time,” says Rangila. “Swarg me jaana aur T-Series me gaana ek hi baat tha (Singing for T-Series was like to going to heaven).”

“I had hit upon an idea,” he says. “In those days, dholak and jhaal (traditional Indian instruments) were prominent instruments in Bhojpuri music. ‘Musical’ nahin tha us samay (There was no concept of ‘musical’). So I thought, ‘Let’s do a new thing. Let’s sing ‘musical’ Bhojpuri’.” ‘Musical’ is what Rangila calls songs which are composed using contemporary Western instruments “such as the guitar, the keyboard or the mouth organ”.

In 1995, Giri went to the T-series office in Noida on the outskirts of Delhi. He said to the guard at the front door that he wanted to meet Gulshan Kumar (the T-Series’ founder). He wasn’t allowed to pass. “What else would the watchman have said?” says Rangila. “‘Who are you? What are you worth?’ It’s a company where so many musicians would have gone looking a chance to make it. But he didn’t let me enter, so that was the end of it.”

He adds: “On my journey back, Poore raaste gaali dete hua aaye T-Series ko (I kept on cursing T-Series during my entire journey).” Giri didn’t approach any other recording company. “T-Series hi sab kuch tha (T-Series was everything),” he reiterates.

To support himself financially, Giri took up a job in a Delhi garment shop, trimming extraneous threads from clothes. Every day at work, he would “remove threads from 30 to 40 shirts”. He earned Rs. 750 per month. Simultaneously, he kept singing ashtjaam and kirtan songs at local performances. In 1995, at one such show at the Sagarpur Shiv Mandir in Delhi, Giri held his own against a kirtan singer who was notorious for heckling his competitors. At the end of the show, Sharma (Rangila doesn’t remember his first name), an owner of a fledgling music company called Ganga Music, gave Rangila his card. “I thought: Now the company guy himself is calling me! Now I’ll become a star!”

Giri reached the address given on Sharma’s card. He had expected something like the T-Series building and was dejected when he realized that Sharma’s office was merely a section of his modest home. “But I was sure I wanted to sing songs my way. So I told him to do a ‘musical’,” says Rangila. There was a catch. Producing a ‘musical’ album would cost Rs. 40,000 and Giri was a new singer. So Sharma made him sign a bond for Rs. 40,000, which Giri would repay by recording his first four albums with Ganga Music for free.

The means for producing an album were in place. But Sidheshwara Nand Giri, known as Guddu Giri then, needed a new name that would appeal to a younger audience. “Guddu was my pet name back in my village,” says Rangila. “Lekin blood mein jo ho jaata hai naa ki humko aisa geet gaa kar youth ko khush karna hai (But there’s this thing that happens in your blood, right? That you want to sing songs that make youngsters happy).” The big Bollywood hit running in the theatres at the time was Rangeela (meaning ‘Colourful’). “That Rangeela film had done quite well,” Rangila recalls. “Toh lagaa diye (So I took the title for my surname).”

Rangila’s first release was titled Jawaani Ka Toofan (The Storm of Youth). “Log 100% sure hote hain na, main 300% sure tha ki yeh album hit hoga (People are 100% sure sometimes, right? But I was 300% sure that my album would be a hit),” he says. According to Rangila, the album must have sold more than “1.5 lakh copies”. “Uske baad sapna poora hua (After that, my dream got fulfilled).”

Rangila recorded his next three albums with Ganga Music in a span of two months. But they couldn’t surpass the success of Jawaani Ka Toofan. They were all, as he puts it, “medium”. But it was Rangila’s fifth album, Ja Jhar Ke, that was his big ticket. Rangila had already recorded four albums with Ganga Music for free, and now was the time to cash in. But Sharma refused. “Jhagdaa ho gaya Ganga company se (I fought with Ganga company),” he says. “He wanted that I keep on singing for free for him. Par tab tak T-Series ko bhanak lag gayaa thaa (But by that time T-Series had noticed me).”

In 1998, Rangila re-recorded Ja Jhaar Ke with T-Series. He was paid Rs. 25,000. “Back then 25,000 was worth what 25 lakhs is worth now.” He also re-recorded his first four albums with T-Series. Rangila was a singer with T-Series now. “Phir toh kya tha? Phir toh raaj chalne laga humaara (Then what? Then I started ruling the roost).”

***

The story of Bhojpuri music, in our times, is inextricably linked with the story of Bhojpuri cinema. In 2003, the Bhojpuri film industry was enthused with the release of Sasura Bada Paisawala. Made on a budget of Rs. 35 lakh, the film made more than Rs. 4.5 crore at the box-office. Since then, the Bhojpuri film industry has evolved from being a cottage industry to a behemoth that makes more than 100 films a year, hosts its own award shows, and has enlisted big Bollywood stars like Amitabh Bachchan, Ajay Devgn and Hema Malini to act in its films. Avijit Ghosh, the author of Cinema Bhojpuri, examines the coming-into-its-own of the industry in a Times of India article titled Mofussil’s Revenge. “The Bhojpuri film industry’s revival isn’t only about a regional genre finding its market,” he writes. “The [hinterland] audience seems to be telling mainstream Bollywood: We want our own smells and sights in the movies. As in post-Mandal politics, regions and communities are asserting themselves through cinema that suits their aesthetics.” As Bollywood turned its gaze westwards as well as towards a more urban multiplex audience, Bhojpuri cinema took over some of the ground it ceded. It fulfilled the desire of a section of Indian rural and rurban populace for entertainment rooted in the hinterland. Bhojpuri music—both film and non-film music—is the product of a similar demand and an expression that most from its home state can easily identify with.

Also, the market for Bhojpuri music and cinema isn’t just people living in Bihar, but also many migrant workers in states such as Delhi and Maharashtra. These songs remind them of what home sounds like in a foreign land. “Jiska des, uska bhes (A person’s culture is determined by his or her homeland),” says Pankaj Thakur, who hails from Katihar, in Bihar, and works in Pune as a cook. “Maharashtrian people understand Marathi songs. Similarly Biharis understand Bihari songs. Even now I have around 300 songs on my mobile.”

This Bihari diaspora accounts for a more widespread audience for the songs of singer-songwriters like Rangila. Songs which are now being rediscovered on the internet. In the last few years, aided by YouTube, Bhojpuri songs have re-surfaced online and acquired cult status. For segments of the Indian and international urban audience, comprising both Biharis and non-Biharis, these songs—owing to their sub-standard production qualities and crude lyrics—have become a source of amusement and derision. Surabhi Sharma, the documentary filmmaker whose documentary Bidesia in Bambai explores the lives of Bihari migrants in Mumbai empowered by Bhojpuri music, finds this sort of simplistic outlook problematic. “If you see singers like Guddu Rangila or Rampat Haraami (another popular singer of risque Bhojpuri numbers), I will be still wary of dismissing them as misogynistic,” she says. “Of course, there’s a misogynistic angle to it. There’s a desire being created out of objectifying a woman. That is central. But the reason why a VCD or a YouTube link to a Guddu Rangila song really looks irksome and disturbing is because it exists outside of any context. There’s a lot more that you can listen to in songs beyond the literal text. To pull out the lyrics of the song and try and evaluate the entire musical tradition through it, that becomes a huge problem.”

True. It could be argued, however, that it’s not the VCDs or YouTube videos that place these musical traditions out of context as much as singers like Rangila themselves, simply with the lyrics they choose to pen, which alters the nature of the song drastically.

Playful irreverence, often bordering on vulgarity, has been an ingredient of folk songs that have been part of the Indian hinterland’s longest held traditions. For example, Gaari (derived from the Hindi word gaali, which translates into ‘swear’) songs are integral to Bihari weddings. One of the many rituals in such a wedding is a Dwar Puja— performed to welcome the groom as he arrives with his baraat (the groom’s family) at the bride’s door. The bride is led to the mandap by her friends and cousins and they sing cheeky, coarse songs, flouting ideas of conventional familial propriety, to taunt the groom and his family. The songs are quite unsparing and target especially the bride’s future father-in-law. In fact, the 1986 Bhojpuri film, Dulha Ganga Paar Ke, contains one such gaari song, Chala Sakhi Mil Ke, which opens with the lines: “Swaagat me gaari sunayin, aa chala sakhi mil ke/ Inka ke langte nachayin, aa chala sakhi mil ke (We will welcome with swearing/ Come friends, all together now/ We will make them dance naked/ Come friends, all together now)… ”

This tradition helps see the gender roles in a renewed light—here the women are assertive and vocal—and cautions one against the easy sanctimony listeners often adopt while hearing anything that’s even remotely bawdy. Gaari songs are examples of how perceived vulgarity can function instead as an agent of creativity, possibly, and even social cohesiveness or simply great fun.

What becomes unsettling, however, is when the explicit content has sprung up not purely out of tradition or a creative urge, but from a need to pander to the base demands of as large an audience as it is possible to usurp— for profit.

Manoj Tiwari, a prominent actor and singer in the Bhojpuri film industry (he played the protagonist in Sasura Bada Paisawala), has often lashed out against obscene Bhojpuri songs. “I have always maintained that our state should have its own censor board,” says Tiwari. “So that if there are people who are singing vulgar songs then someone will stop them. I feel such songs must be banned. Songs can make you laugh but they should not shame someone. And if there are people who are singing those songs, then they should be punished.”

“I am not in favour of banning anything,” says Avijit Ghosh. “Banning books, music, films… Once a culture of ban starts then you don’t know what to ban and what not to. So this whole trajectory of debate goes into a different realm.”

Talking specifically about Rangila, Tiwari says, “He has also sung some good songs. But he couldn’t understand which songs of his were liked the most. 1998, 1999 was a good phase of Guddu Rangila, when he had sung Ja Jhar Ke. It was that song that made him big. Ja Jhar Ke didn’t have any vulgarity as such. But the problem was he saw it is a vulgar song— so he couldn’t understand what made him successful.”

Tiwari also feels that such songs project an image of the state and the language that is misleading. “These songs cause a lot of harm to the Bhojpuri region. For instance, I was doing a show on Life Ok, Welcome – Baazi Mehmaan Nawazi Ki, which had a lot of actresses like Ragini Khanna, Negar Khan. And whenever I used to talk about Bhojpuri and whenever someone wanted to put me down, people gave me examples of those (vulgar) songs,” says Tiwari. “But, the fact is, there are also many singers (in the state) such as Bharat Sharma, Sharda Sinha, who have sung many great songs, and their fans are all over the world.”

Kalpana Patowary, who hails from Assam, is another famous mainstream Bhojpuri singer. Like other mainstream Bhojpuri singers, she also began her career by singing a lot of songs with overt sexual connotations. But, unlike others, she didn’t get stereotyped and managed to diversify her oeuvre. One way she did this was by singing different kinds of songs in various languages— Hindi, English, Marathi, and a host of other regional languages. She’s appeared in Coke Studio’s Season 3 and has performed for music festivals such as the Rajasthan International Folk Festival and the NH7 Weekender. In 2012, she released The Legacy of Bhikhari Thakur, a Bhojpuri folk album based on the songs of the celebrated Bhojpuri playwright, Bhikhari Thakur. But, today, 11 years later, Patowary finds herself disillusioned with the very music industry that catapulted her to fame: “Today the state of (Bhojpuri) music is such that often I have to leave the studio, refusing to perform. I have to return the money. I have to leave a lot of songs just because of the lyrics,” says Patowary in the documentary, 50 Years of Bhojpuri Cinema. “Recently, there was a song where the lyrics were about a crooked button on a blouse and it also mentioned the word petticoat. I felt that was cheap. Later they changed the lyrics though. If you want to show sexual pleasure then of course you should, because it’s a part of our life, but it should be shown in an aesthetic manner.”

What is the reason for such songs continuing to flood the market then? One answer could be that the social, economic and cultural realties of more affluent and educated Biharis have little in common with their poorer counterparts. “Do you think the white-collared Biharis—the IAS officers, the management executives—identify with Bihar at all? They are not very comfortable with their Bihari identity,” says Ratnakar Tripathy, Senior Research Fellow at the Asian Development Research Institute. Tripathy believes the “white-collared Biharis refuse to support Bhojpuri” as a language and culture, and “when someone does it, they rubbish them”. He says: “It’s a very strange relationship between the lower classes and upper classes in Bihar. The Bihari elite doesn’t patronize Bhojpuri and the ones who patronize Bhojpuri tend to vulgarize it, at times. So this is a cultural dead-end.”

Patowary adds: “I have seen in the towns of Bihar that the younger generation says: ‘In our homes, we speak Hindi. We don’t know Bhojpuri.’”

In 2009, when Sneha Khanwalkar and Varun Grover went to Bihar to research sounds and music from the state for Gangs of Wasseypur (Khanwalkar was the music director, Grover the lyricist), they did so, according to Grover, “with a blank slate”. While digging, they discovered how the local popular culture had shaped and dictated the aspirations of Bihar’s youngsters. Grover has an interesting story.

When Khanwalkar and Grover met the 16 year old Deepak Kumar for the first time, he was a “very simple kid, very timid. He wasn’t even sure if he could sing. He had come with his Guruji, and was carrying a harmonium,” remembers Grover. “In fact, he wasn’t even a chela (disciple), because his Guruji had said that, ‘He has just started singing. It would take him years.’” As Guruji’s more experienced disciples auditioned in front of Khanwalkar, Kumar stood quietly in a corner. Despite his Guru’s reservation, Khanwalkar persuaded him to sing. He said he would sing a song of Pawan Singh (a popular mainstream Bhojpuri singer, known for a song named Lollypop Lage Lu or ‘You Look Like A Lollypop’). Khanwalkar liked his voice and Kumar ended up singing two songs in Gangs of Wasseypur I: Moora and Humni Ke Nagariya Chhoda Re Baba.

Khanwalkar and Grover met Kumar six months later for another recording, when Gangs of Wasseypur I’s music had already been released. By this time Kumar had become a ‘star’ of sorts in Bihar. “He came with the CD, and he said, ‘Bhaiyya mera na apna CD, apna album aa gaya hai (I have got my own CD, my own album released).’ The first album he got as a 16 year old was called Petticoat mein… some Bhojpuri word, I don’t remember,” says Grover. “So that’s what, no? The moment you become popular, you get to do this kind of lewd stuff. He didn’t get to do another album like Gangs… though he had proved himself in that kind of genre, that kind of music. All he still got to do was this kind of crude stuff. And he grabbed that opportunity.”

***

Naigaon is one of Mumbai’s Northern suburbs but the ease with which it flouts most Mumbai rules makes you wonder whether it’s a part of the city at all. For instance, all the auto-rickshaws at Naigaon station ply on a ‘sharing basis’. When you hail one, the driver refuses to budge till he has three passengers seated at the back and two at the front, including himself. As you drive off, cramped, you see many open spaces— mostly lush green fields. The buildings, just a few storeys high, are nowhere near Mumbai’s skyscrapers, but they look as though they’ve been around for a while. The roads are rocky and uneven. There are not too many people or cars around. In fact, Naigaon could easily pass of as suburban Patna.

It’s here that Guddu Rangila chose to buy a flat. It is a modest space with just one bedroom, a living room, a kitchen and a bathroom. It’s been over a month since my last interview with Rangila who’s still asleep even though it’s late in the afternoon. Instead, eyeing me suspiciously from his perch on a couch in the living room is a man wearing a white vest that clings to his protruding stomach and a pair of blue baseball shorts. Mritunjaya Mastana keeps bustling in and out of the room, looking busy, putting things in order before “Bhaiyyaji” wakes up.

Rangila has moved in recently. The furniture in the living room seems awkwardly arranged. The couch with the man in the blue shorts is at one end while another similar sofa is placed as far away from this one as possible— so that people seated on each would have to yell at each other to be heard. A table with a glass top is sandwiched between this other sofa and a TV set. Huge posters of new or upcoming Guddu Rangila movies take up most of two of the walls: Sasuro Kabhi Damaad Rahal (Because The Father-in-Law Was Also Once The Son-in-Law), and Piritiya Kahe Ke Lagawla (Why Did You Fall In Love With Me?).

“Aap kyun aaye hain yahan? (Why have you come here)?” asks the man in the blue shorts.

“Interview ke liye (For an interview),” I say.

“Usse humara kya fayeda hoga (How will it help us)?”

While switching on my laptop, I say something about the importance of knowing where an artist comes from and what bearing this may have on his work.

“Yeh Apple ka sign mein light jalta hai kya (Does the Apple sign glow)?” He stares intently at the laptop. “Shining bahut hai ismein. Lagta hai radium laga hai (It shines a lot. I think it has radium).”

I nod.

A few minutes later, he asks for my laptop and notices that I have jotted down our conversation on a word-file. He seems uncomfortable with this at first, but eventually this gets us talking.

His name is Deepak Mandal. He heads a “tours and travels” company in Mumbai. Before that, he says, “Main naacha karta tha (I used to dance).” He smiles slightly, stealing a quick glance at the bedroom, where Rangila is sleeping. “In Kalpana Patowary’s group.” He had wanted to act in films, but had learnt that it would cost him Rs. 20,000. So he decided to try his hand at the transport business instead.

A few minutes later, Mastana runs into the living room, looking very harried. “Bhaiyyaji uth gaye hain. Unko cigarette chahiye (Bhaiyyaji has woken up. He needs a cigarette),” he says. Mastana manages to find one and rushes back out. Ten minutes later, Rangila enters. Mandal vacates his couch for him and sits next to me. Rangila’s eyes are puffed. He looks out of the balcony and lights a cigarette.

An odd silence floats through the room. The interview begins. Mandal remains sitting next to me like a watchful bodyguard, peeking curiously at times into my list of questions, often answering, out of turn, questions put to Rangila.

But this isn’t the only thing that makes striking up a conversation with Guddu Rangila difficult. Rangila has three ways of dealing with tough queries. Either he remains non-committal, like a politician, and says: Apni apni soch hai (Each person has his or her own point of view).

Or, when feeling more verbose, he comes up with bizarre non-sequiturs. Here are a few of the most commonly employed:

Mard ko dard nahin hota (A man doesn’t feel any pain).

Dulhan wahi jo piya mann bhaaye (An ideal bride is the one who pleases the husband).

Chalti ka naam gaadi hai, nahin chala ton kabaadi (If it works, and moves, it’s a car, if it doesn’t then it’s rubbish).

He utters such sentences, often out of context, as if they’re the smartest one-liners on earth, then sinks back into silence.

As a third option, as if this wasn’t enough in itself to make you flee, he loves to reinterpret Hindu mythology. He frequently cites absolutely irrelevant tales of the gods Shiv and Parvati or—and this is an obsession—how we are living in the wrong yug (age), and how kalyug is utterly rotten, to validate his actions and beliefs.

We begin by talking about his detractors. “People who are above the age of 50 don’t like my songs,” says Rangila. “In fact they shouldn’t even be alive. They should all die. They are just a burden on this planet.” That simple. “They would like all songs related to Gods,” he continues. “But they won’t have anything to do with girls. So, I tell them that in your age, you would have also played a lot of gilli ganda, done a lot of things. Now you should sing bhajan and earn punya.” Gilli danda, a popular Indian game akin to cricket, is a euphemism for sex for the purposes of this conversation.

I plod on. Rangila’s songs and videos are obsessed with a woman’s physical attributes. She is an object to be in awe of, possessed or lampooned. There are constant references to her body parts, how she’s being a tease, or how the male (in most cases this is Rangila himself) will win her over finally. But that could be just Rangila the performer, playing to the gallery. What does Rangila, the person, believe in, really, when it comes to the opposite sex?

These pearls of wisdom:

“A girl and a boy can never be friends. If there has to be friendship, then it should be either between boys or between girls.”

“You fall in love only after you are married. Anything that’s before marriage is meaningless.”

“You should love whom you get married to. What kind of love is there before marriage? I didn’t even know of something called a girlfriend before marriage. Anyway, it’s a wrong system. What’s the need?”

For someone who writes and sings the most lewd lyrics imaginable, Rangila’s personal outlook is surprisingly conservative. He was married in 2002. “It was an arranged marriage,” he says and appears reticent when I ask him for further details. He has two children.

“I fall in love every day,” he says. “I had closed pyaar ka (love’s) factory in 2002. There’s no love in this world. There’s only selfishness.”

‘Closed love’s factory’? I ask him to elaborate.

“In 2002, in my album Humra Hau Chaheen, there was a dialogue: Tell me one relationship, which doesn’t revolve around selfishness? When a girl is born to parents, they are not that happy as opposed to when a boy is born to them. Why is it like that? Isn’t that selfishness? Because a girl will get married and go away while the boy will take care of them even when they are old. The love between a husband and wife is also centered on selfishness. Why don’t a boy and boy get married? See, when it comes to husband and wife, if you don’t earn do you think the wife will care about you? She wouldn’t. You would have to earn. Isn’t that selfishness? If you won’t earn, what would she eat? A girl gets married to a boy because she can’t earn. There’s selfishness everywhere.”

I ask Rangila about his own marriage again, and whether he believes it follows this principle. “When you get a lot of love and respect outside, you won’t get the same at home, and vice versa,” is all he says. “Because if you’re getting a lot of adoration from outsiders you won’t have time to devote to your family.”

When I ask him about the obscenity in his songs, he comes up with the strangest suggestion. “Recently, I sang a song, Ghus gayil, phans gayil, adas gayil (It went inside, got stuck and stayed there),” says Rangila. “People would think that it’s vulgar. What do they know what I have written? I have actually written this song about Asaram Bapu. It’s absolutely clear.” I stare at him, puzzled. Rangila has a smile playing on his lips.

I ask him about another song. The lyrics go: Khol ke dikha de gori laal rasgulla, toh ke karayeb hum dudhwa ke kulla (Show me your red rasgullah/ Then I will make you gargle with milk).

“What does that mean?” I ask him.

“This song is not mine. I don’t think I remember this song,” says Rangila.

I tell him the video of this song on YouTube features him and also the vocals are unmistakably his.

Rangila’s reply: “No song is bad. The kind of sunglasses you wear determines the kind of song you will see. If you wear red sunglasses and think you will see black, then that’s not possible. If you wear green, you can’t see white.”

Rangila’s songs are disturbing not simply because they are hyper-sexualized and cater to his audience’s baser instincts, but because they eschew any female participation. In most of his songs, there are no female vocals. The only role for a woman in a Guddu Rangila music video is to evade the advances of a plethora of men. She is on guard, and never voices her opinion. An unsettling power equation to say the least. We never really know what a woman is thinking about when Rangila talks about her body parts, expresses his discontentment about the fact that she might not be a virgin, or points towards her clothes and demands that she takes them off.

This absolute absence of consent—or conversation—in his songs is telling. Take Ae Tengra Ke Didi (Hey, Tengra’s elder sister), from his album, 80 Na 85 Humra 90 Chaheen (I don’t want 80 or 85. I want 90), Rangila places his fingers close to the girl’s breast and sings: Nibuwa gotail bate ras khacha khoch ba, gadrol jawani dekhi man humar gach ba (The ripe lemon has enough juice, and seeing your nubile body makes me happy). The camera zooms in. All this, while the girl makes it quite clear that she’s not interested— resisting his advances, rolling her eyes. Rangila appears to acknowledge this for a moment. He sings: Jabbe hoi man tor tabbe chahi (I want it only when you are ready).

But, soon after, he changes his mind: Prince guddu maani nahi chahe hoi phaansi, ihe baate pahile tor ijjat ke naasi. Guddu ke jab mann hoi tabbe chahi (Prince Guddu will not listen to you even if that means he’s hanged, he will be the first one to ravage your honour. Guddu will get it when he wants it). At the end of the song, the girl finally lets herself be heard. And she says, “Jab na maanbe tab chal (If you don’t agree, then what’s the point. Let’s go)”. A thought here. What if she had refused?

I ask him about this and the recurring imagery in his songs and videos— of a woman hounded by him or by hordes of men, trying desperately to resist their advances, then yielding. “It might be the thinking of people who criticize me. The world doesn’t revolve around what some people think about my song. Don’t you think?” Rangila retorts. He is opaque, calm, his face almost expressionless.

Then, his voice booms: “Ladki cheeze aisa hai, sab koi dekhta hai (A girl is such a thing, everyone looks). Is there any harm in looking? God has made something good so that it may be seen. Of all the pleasures in the world the most beautiful is nain bhog (the pleasure you get from looking at things). If I don’t see, then that means I am insulting her. God will feel bad. He will think, ‘I made someone so beautiful and no one is looking at her’.”

It’s not so much the outburst that’s disturbing as the way he says it. I wait for Rangila to break into a chuckle at the end. He doesn’t. He is staring at me with great sincerity, with an almost grim demeanour. His manner resembles that of a priest at a sermon.

In the last couple of years, Rangila’s songs have begun featuring a few female playback singers at times. He is unhappy about this: “When I used to sing everything by myself it was better. I used to sing the female parts as well. Now, people’s points of view have changed,” says Rangila. “Lekin woh faaltu hai (But that is rubbish).”

“I have written a line on this too,” says Rangila, when I bring him back to the subject of his portrayal of women and women’s issues. “Original balatkaari ke yadi ye duniya me talaasi huile to sabse pahile dewara sabke phaansi bhaile (If there’s a search for the ‘original’ rapists in this world, then brothers-in-law will be the first ones to be hanged).” He hates brothers-in-law apparently. I mention that he has a similar reference in his song Balatkaar Hota Aye Rajau for last year’s Holi. “Shuraat toh wahi sab karta hai (They are the ones who start it),” He says.“Now, a bhabhi (sister-in-law) is like a mother. But people of kalyug are such that they think that the bhabhi belongs half to them. This is wrong. This system is wrong. How can you have fun with your bhabhi?”

Kalyug and brothers-in-law. And the system. That’s what it boils down to. “I merely sing about what’s happening in kalyug,” says Rangila. “Accha hotaa hai to accha gaate hain, kharaab hotaa hai to kharaab gaate hain (If good is happening then I will sing about good things, if something bad is happening then I will sing about bad things).”

He orders an assistant to get him paan (betel leaf). The assistant, who was listening at the door so far, breaks out of his reverie. He goes into the kitchen and returns with a glass of water. “I had asked for paan not paani (water)),” says Rangila. He shakes his head, distraught. I wonder if he will bring up kalyug again. He doesn’t. The minion, flustered by now, runs out to find paan.

Rangila carries on: “I just say what happens. Even Manoj [Tiwari] sang a song… I think the lines were Goriya Apna Dupatta Sambhaal (Fair girl, Mind Your Stole)… I don’t remember exactly. So, he’s saying what’s happening,” says Rangila. “What’s wrong in this? If there’s an odhni (stole), you should cover yourself with it. You are sending a message.”

I ask him what message he had intended to convey with the lines: Bada jaldi badh gayil goriya tohaar mango frooty re, jaldi batawa hum se ki ras kab choosi re (Girl, your Mango Frooty has grown too soon. Tell me quickly, when will I be able to suck its juice)? “There’s a lot of message in that song,” he says. “Now everything can’t be explained. Paani paani ka dosh hota hai (A Hindi idiom that roughly translates into: Every kind of water has its own unique fault).”

“Explain?” I ask him

“It’s better that you don’t understand.”

I coax him. Finally, he says: “You can understand it like this: “Umar ke hisaab se sab kuch badhta ghatta hai. Usi ke anusaar badhna ghattna chahiye. Usse zada kuch bhi badhega ghatega toh wo bura kaha jayega (According to one’s age everything increases or decreases in size. And things should increase or decrease according to age only. If things increase or decrease more than one’s age entitles them to, then they will be criticized).”

There’s that saintly expression again. Rangila is now smiling benignly.

There’s more. “For the festival of Holi, girls should only put colours on girls, same with boys. If a boy puts colour on a girl, it’s wrong. I don’t like that system,” he says. This, despite the fact that almost all his Holi songs milk the sexual flippancy that’s synonymous with the festival. In one of his most curious videos, Kutta Pos Diha (Domesticate a dog by my name), a man is on all fours, barking like a dog while Rangila has a leash around his neck, and is patting his head. There’s also a girl, naturally, surrounded by a bunch of men. In a matter of seconds the music kicks in and everyone begins to gyrate vigorously (except, well, the man on all fours). Rangila sings: “Holi me personal maal bhi ho jaala sarkaari. Abki Holi chahe chale goli, Likh ke kahin khons diha. Taara haun me na rang lagawni tah, mora naam pe kutta pos diha (During Holi even personal belongings become public. In this Holi, even if bullets fire, write this down somewhere: If I don’t put a colour right ‘there’, you can domesticate a dog on my name).”

Mandal, unable to hold himself any longer, interrupts the conversation with his two bits: “If people didn’t like his songs, then how did they become such huge hits? What Bhaiyya said was right— that if you think about the song Ghus gayil, phans gayil, adas gayil (the song “about Asaram Bapu”) in some incorrect way, then where will your mind wander? If people don’t like the song then why are they watching it? They should ignore it.”

This idea, that Rangila sings as he does not for gain but for the people, has been asserted by the singer himself. In song, no less. Rangila sang Bhaasa Bhojpuri Ke (The language of Bhojpuri) which had the line: “Bhaasa Bhojpuri ke uthayi kaise ho? Sabbe suna ta hi oohi to sunayi kaise ho (How do I uplift the language of Bhojpuri? If everyone listens only to those [profane] songs, then how can I make them listen to something else)?”

But today he contradicts this thought. In all these hours spent with him, there has been only one brief moment of honest exchange.

“I wanted to sing like Kumar Sanu,” says Rangila. “But I saw this wasn’t possible, so you have to find a way somewhere. What matters is what the public likes. Public is janta janardhan (almighty). You sing for them, not for yourself.”

But did he ever try to sing those soulful romantic numbers he had dreamt of singing as Giri? To sing “like Kumar Sanu”? “To produce a another album like Bewafa Sanam (‘Unfaithful Lover’, one of Rangila’s rare successful romantic albums) it would take me anywhere close to 6 months,” he lets out. “On the other hand, if I need to make a ‘double meaning’ album, even 15 days are more than enough. In 15 days, I can write around 8 such songs, record them. Bewafa Sanam took around 3 months to write. Because every line has to be powerful. No line can be less powerful than the previous; it has to come from the heart.” He isn’t sermonizing now. He falls silent after this.

Then: “Till 2010, the trend of ‘double meaning’ songs was okay. But now it has become too much. In fact, kalyug itself is ganda (dirty). If we were really pure we would never have been born in kalyug.”

I ask him to define kalyug. “Kalyug is the yug when what we planned doesn’t come to be, and what happens instead is something we didn’t think of in our wildest imaginings,” he says. “It’s the yug where what you’re seeing isn’t really taking place. And what’s happening actually— you cannot possibly see. Don’t you think this is unfortunate?”

It is. As is Rangila in kalyug. Stuck between Kumar Sanu and his ‘double meaning’ songs, between his khaini and his Marlboro Lights, between himself and Sidheshwara Nand Giri.

Our conversation comes to an end. He leaves. Mandal follows him to his room to discuss some business. Mastana enters the living room and plops down on the sofa where Rangila was seated. Dusk has settled in. Since no light was turned on during the interview the living room has grown steadily darker and through the darkness I hear Mastana’s voice: Har kalakaar ka alag alag rutba hota hai, khwahish hota hai (Every artist has his own style, his own forte, his own desires).” I nod silently, still jotting down Rangila’s definition of kalyug.

Then:

“Be it Manoj Tiwari or Pawan Singh, no one has been marked ‘Diamond’ yet in the world of singing. But he’s a ‘Diamond Star’.”

There is a pause. Then Mastana asks me pointedly: “You understand what a diamond is, don’t you?”