-

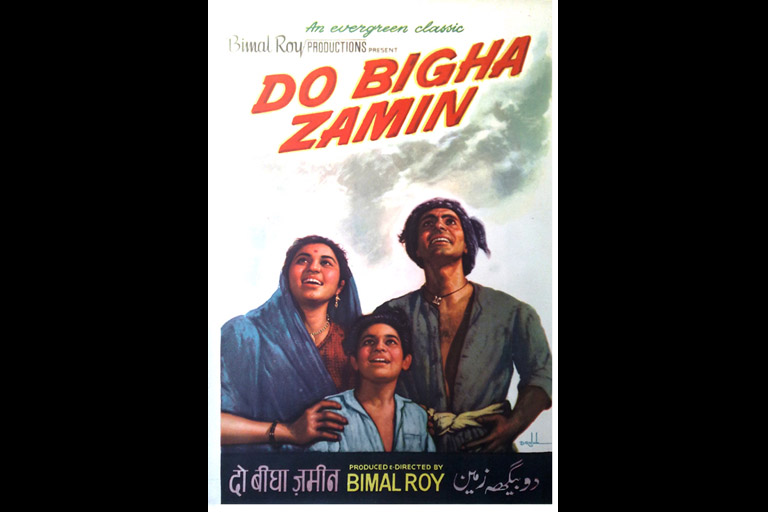

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

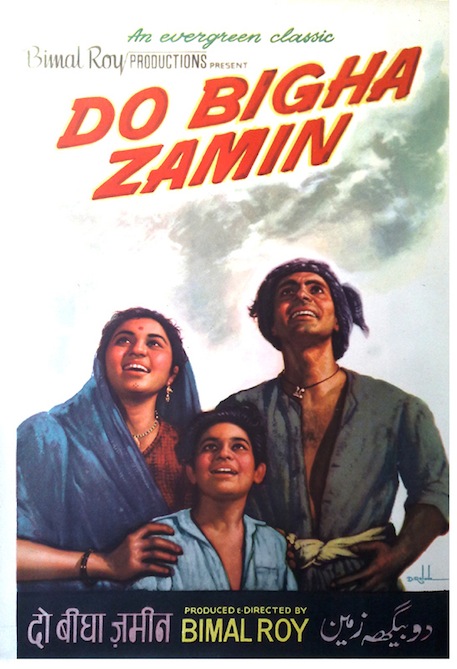

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

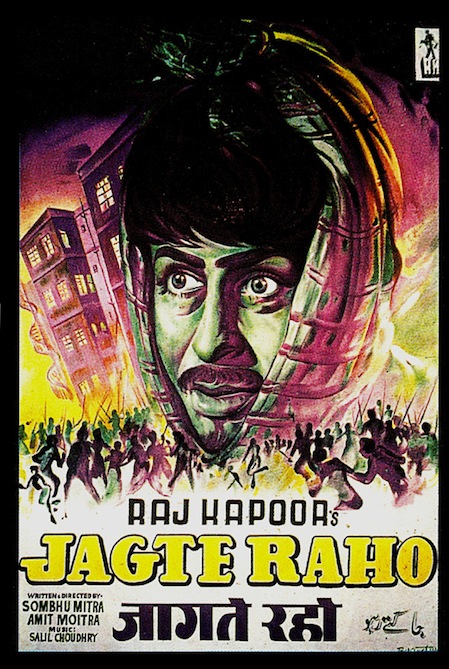

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

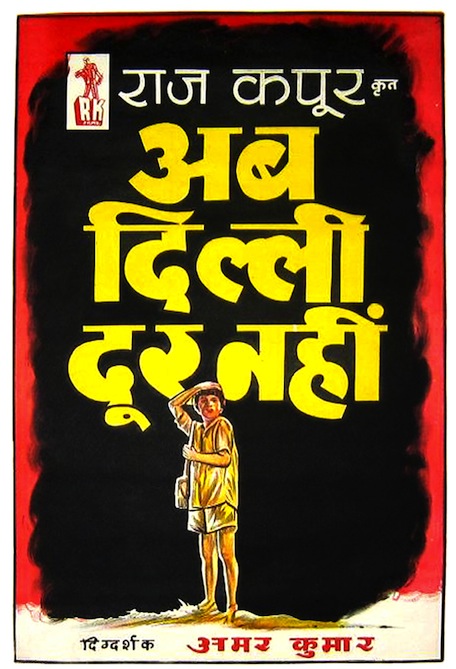

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

Courtesy Yash Raj Productions

Courtesy Yash Raj Productions -

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian)

Courtesy SMM Ausaja (Film Historian) -

Courtesy Yash Raj Productions

Courtesy Yash Raj Productions -

Courtesy Rahul Dholakia Productions

Courtesy Rahul Dholakia Productions -

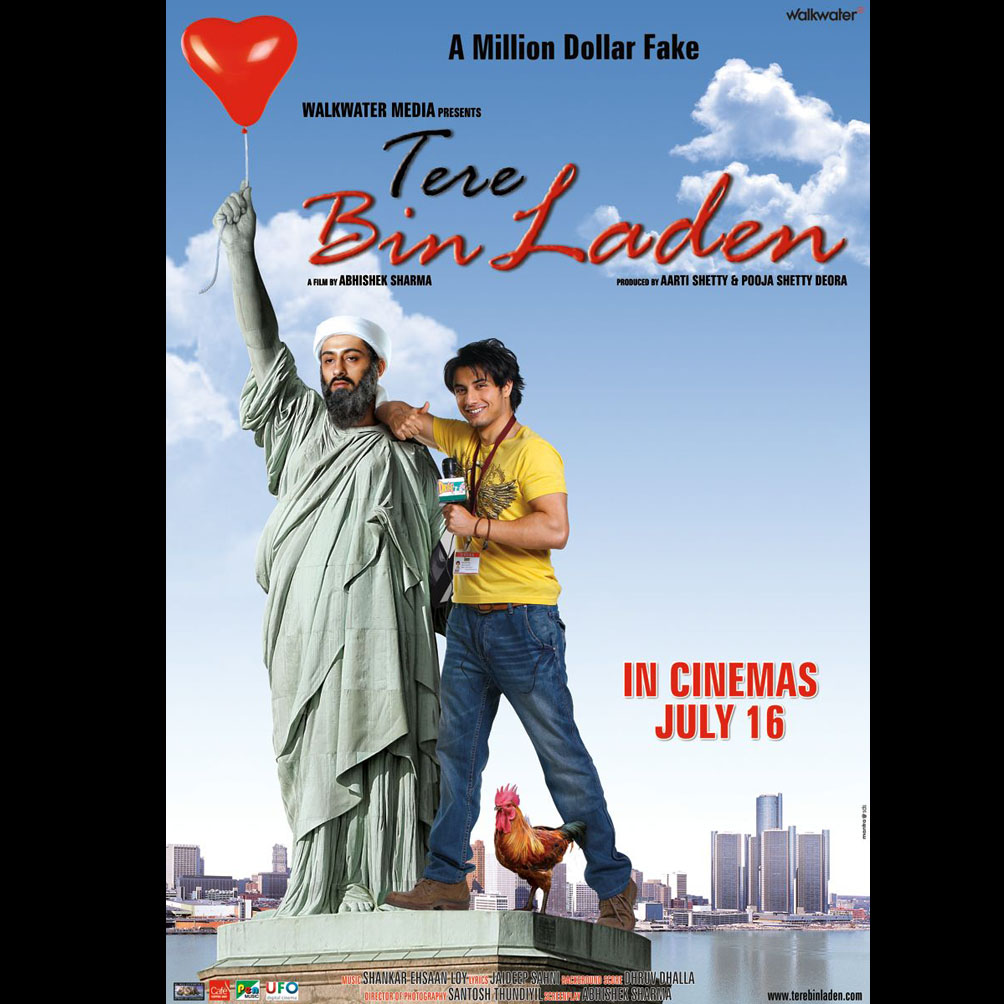

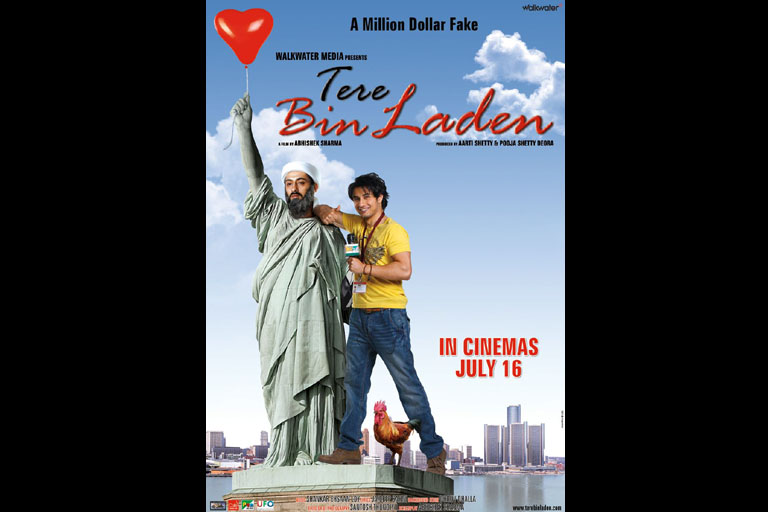

Courtesy Walkwater Productions

Courtesy Walkwater Productions -

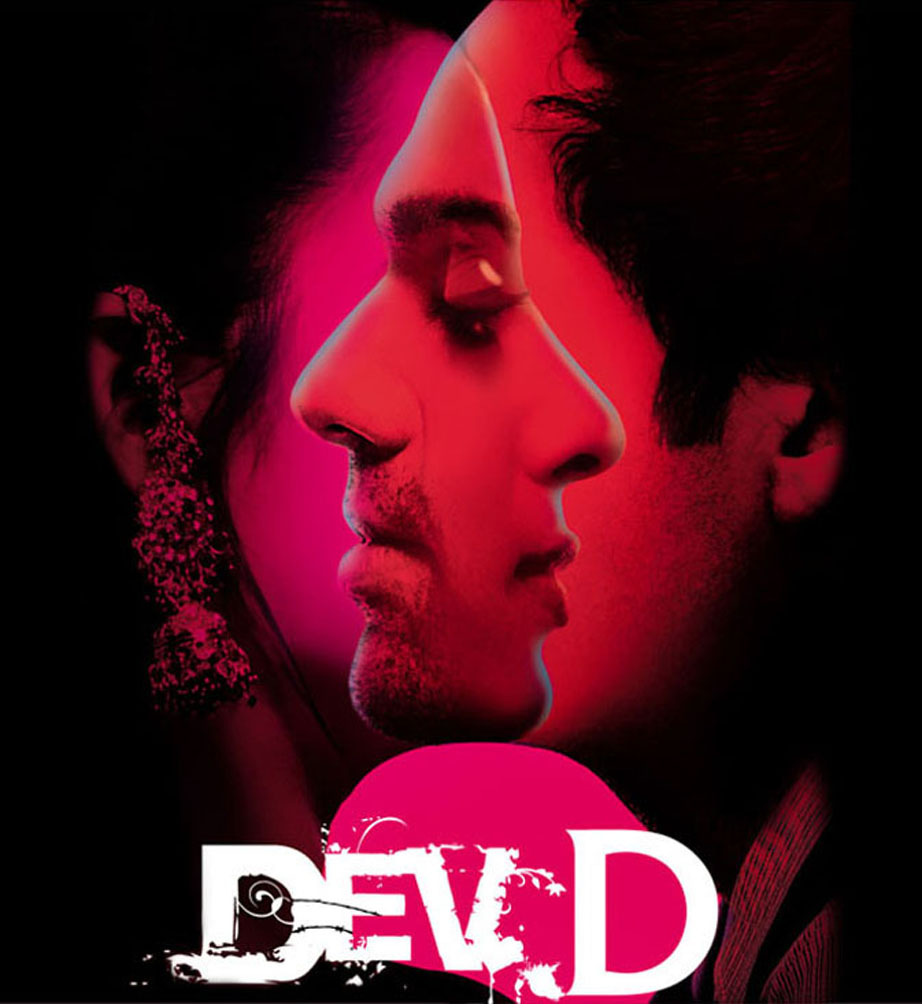

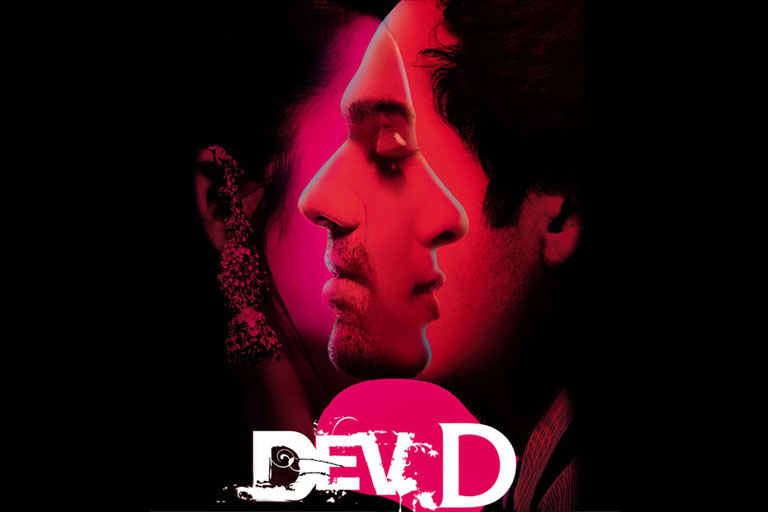

Courtesy AKFPL

Courtesy AKFPL -

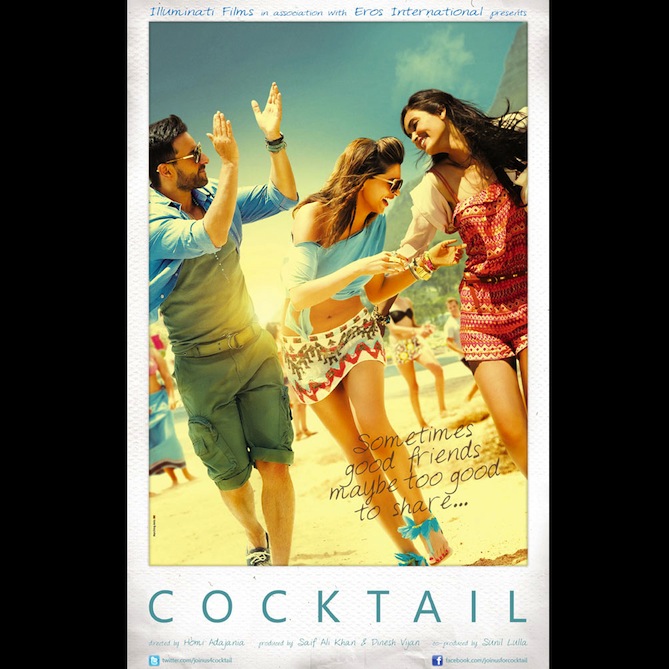

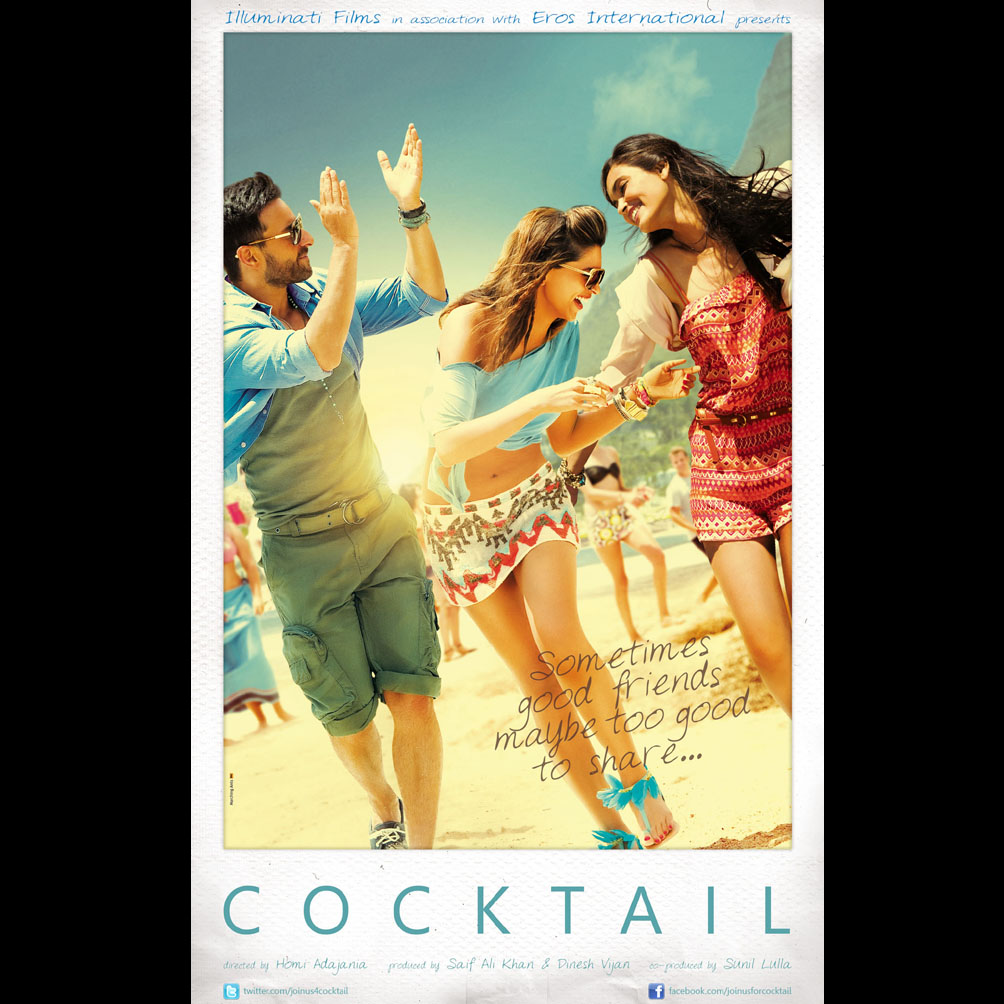

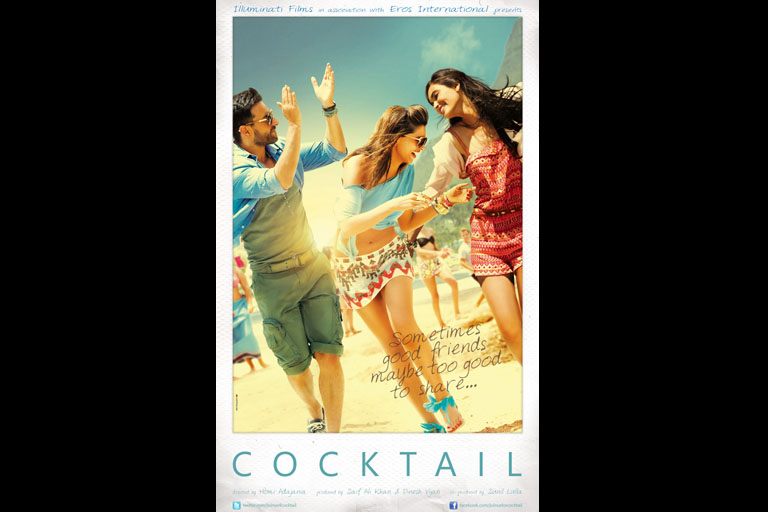

Courtesy Illuminati Films

Courtesy Illuminati Films -

Courtesy Balaji Productions

Courtesy Balaji Productions -

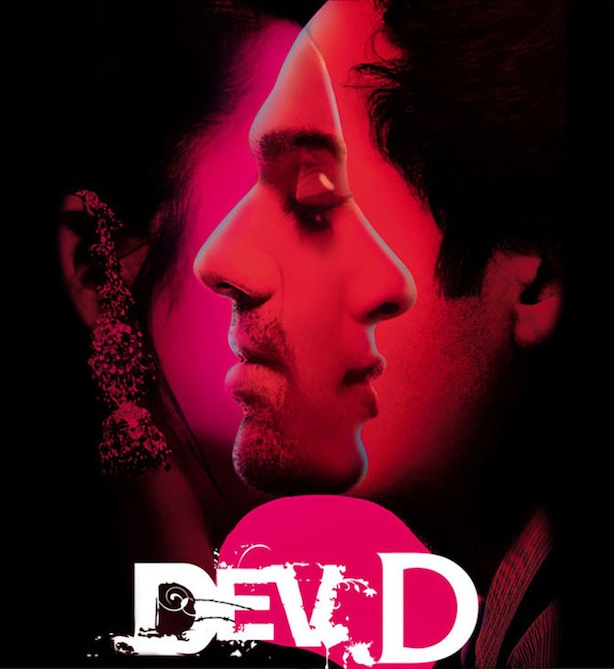

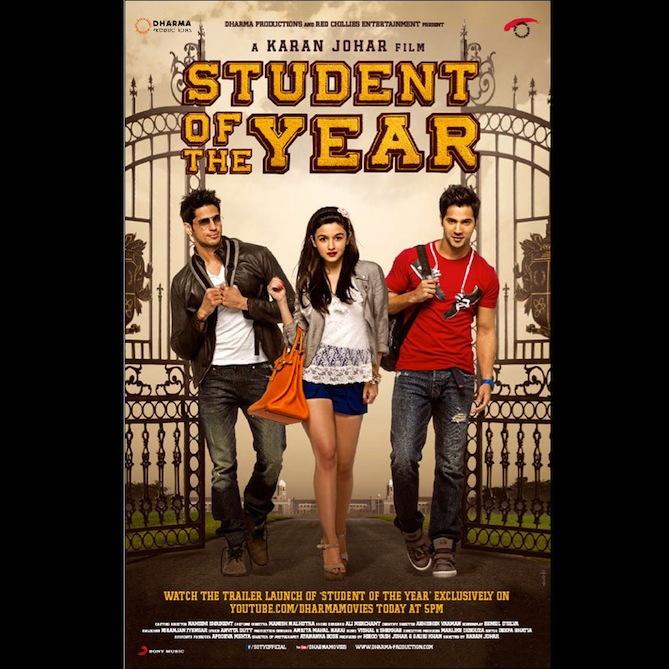

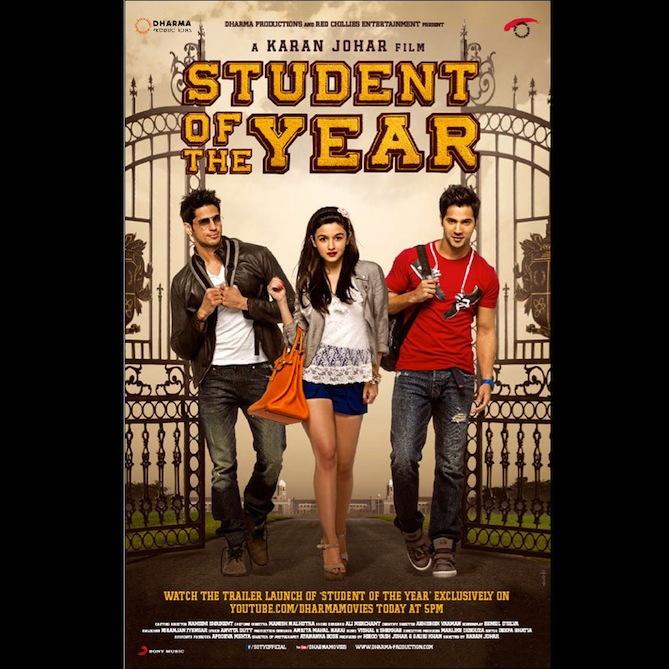

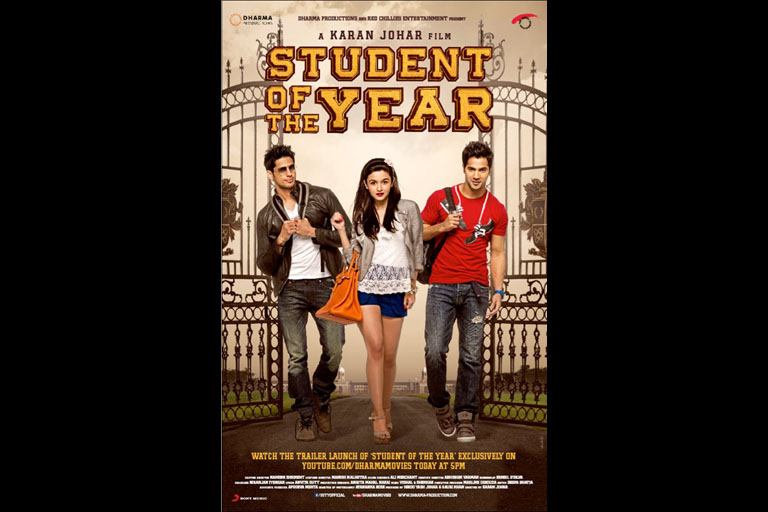

Courtesy Dharma Productions

Courtesy Dharma Productions

Mahmood Farooqui says when it comes to the politics of cinema, who you want to talk to matters as much what you would like to say

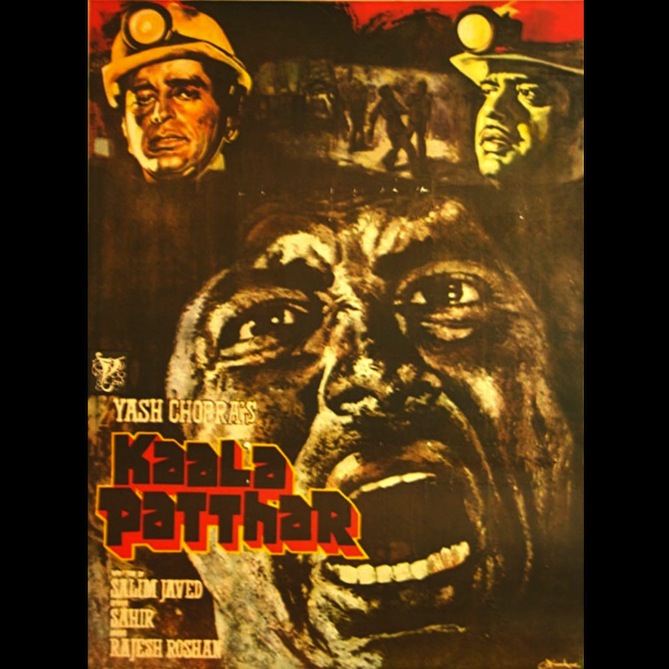

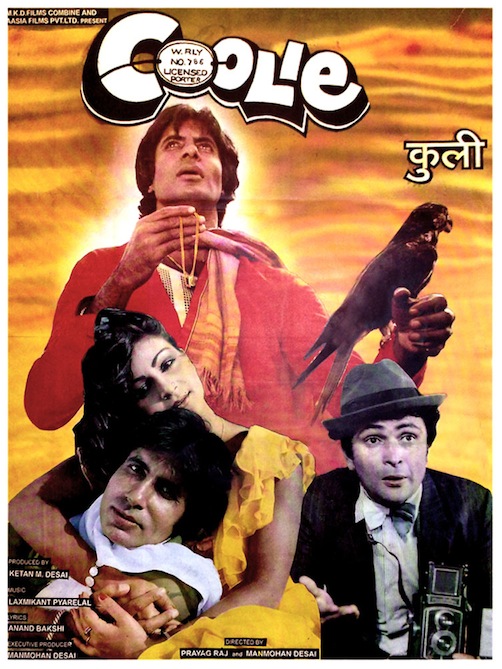

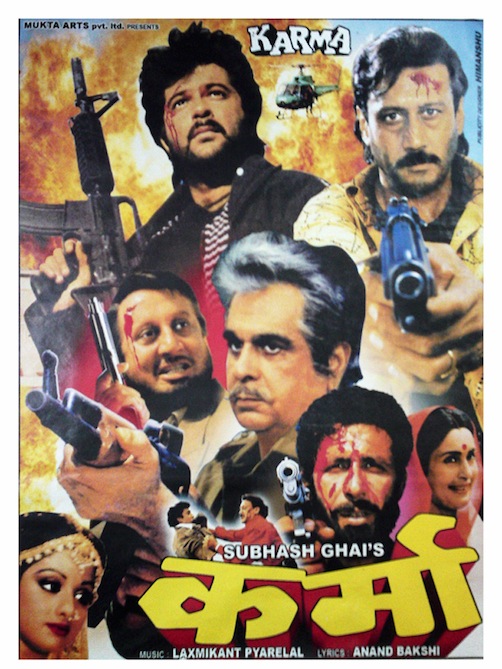

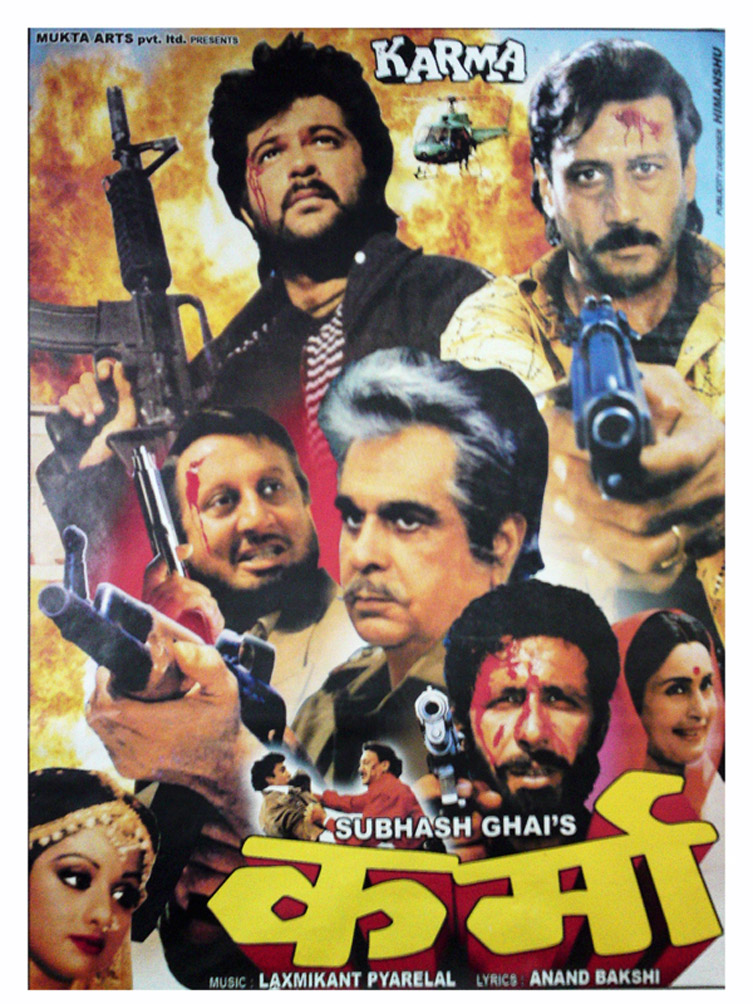

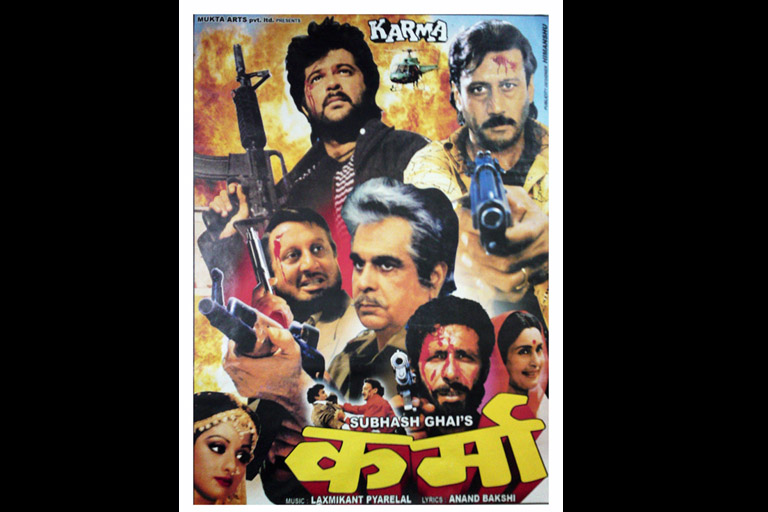

If by ‘political cinema’ we mean the depiction of politicians then Hindustani cinema has been deeply political from Inquilaab to Rajneeti. If political cinema is taken to mean cinema that shows the nation’s concerns then every Hindi film of the eighties, from Karma to Aag Hi Aag has been highly political. Just think of the number of films that have had terrorists as protagonists. Does the depiction of gangsters or smugglers, or the builder mafia and political collusion, make a political film? We have had hundreds of those. Weren’t they making an essential argument about our society? After all corrupt cops, corrupt politicians and corruption in general has been the bane of our heroes ever since I was a child. If political cinema means exposing the society’s ills or making a hard-hitting statement against ‘the system’ then our cinema has done that with unfailing regularity. By stating this I am not necessarily siding with the argument that everything, including your choice of toothbrush is a political act. Of course it is. That would mean that every film made or set in a particular space would be a political film, even if the politics is personal. It would be true, but it would be a trite truism. What then is a political film, especially in the Indian context?

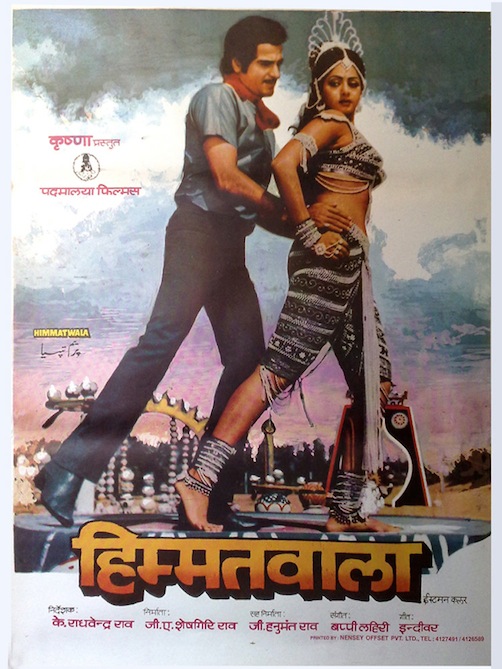

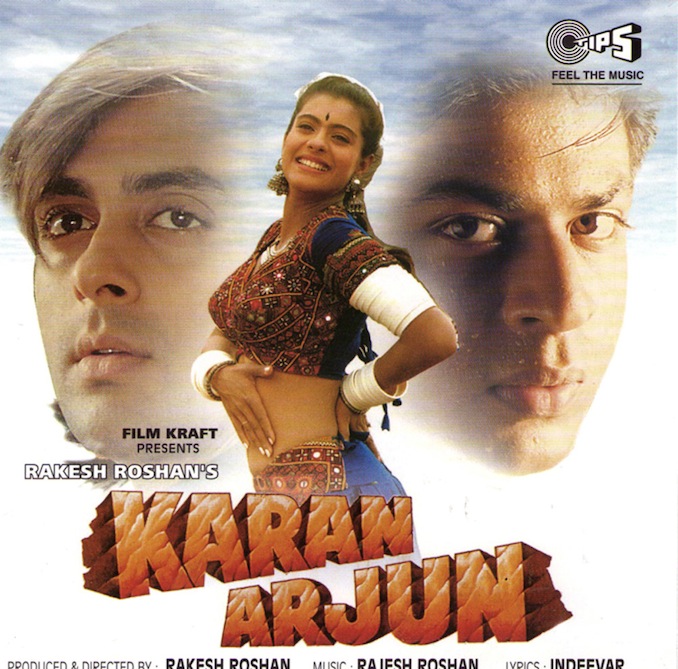

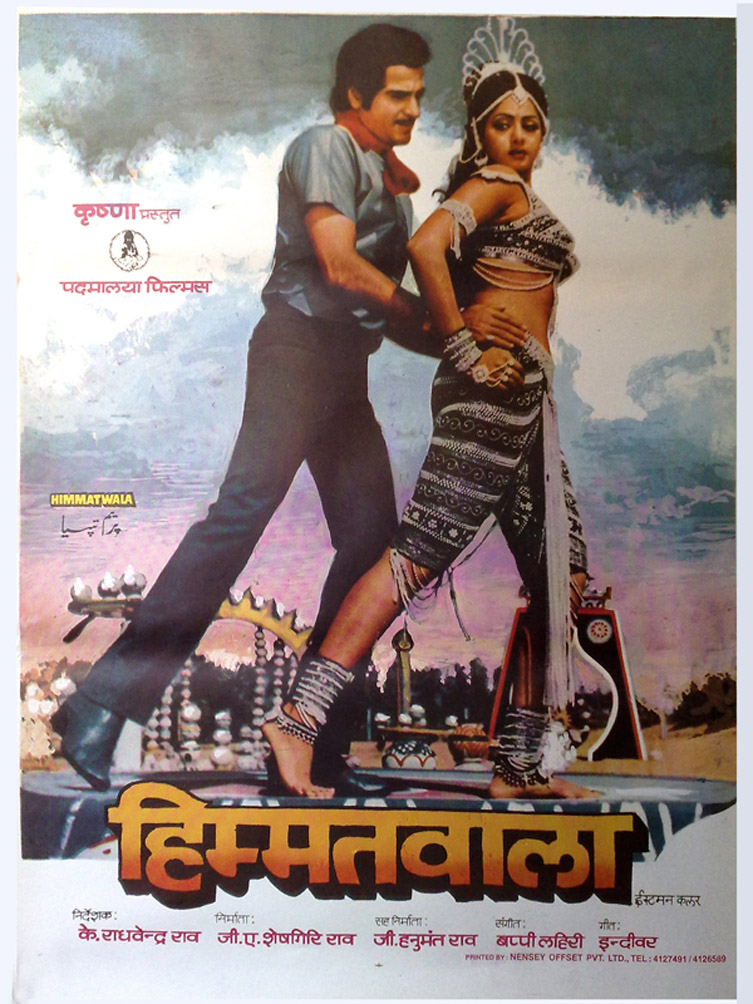

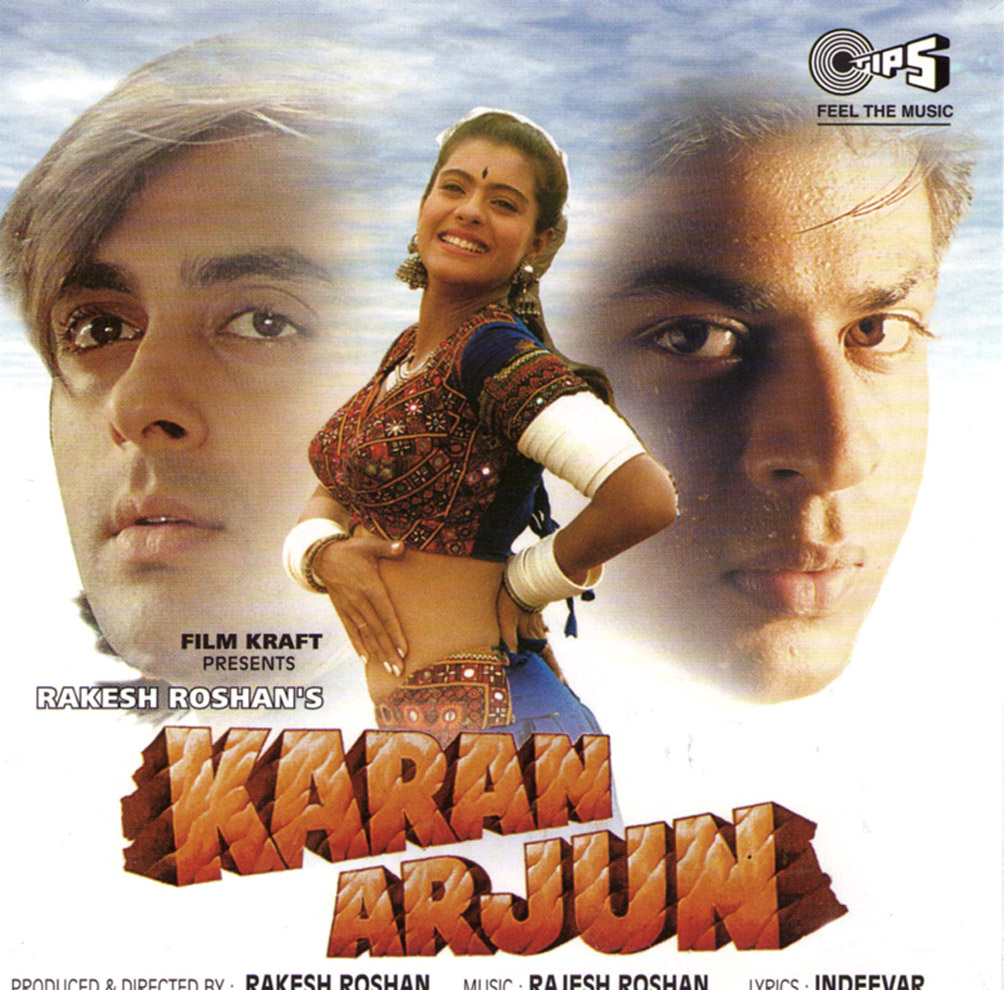

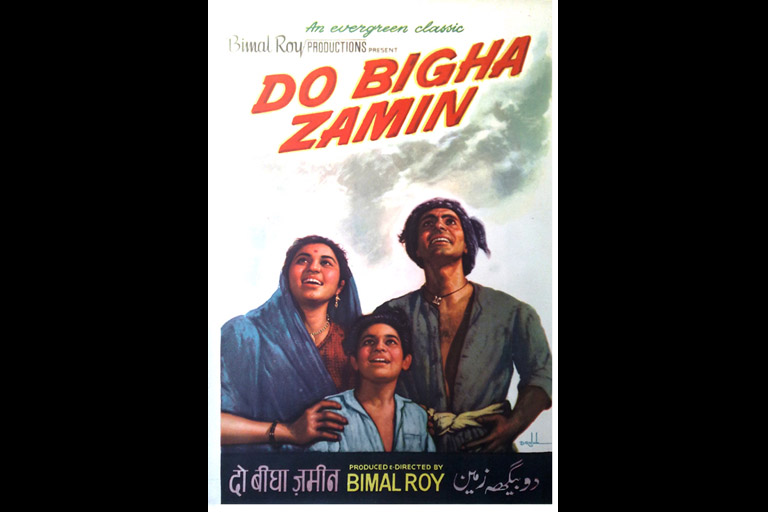

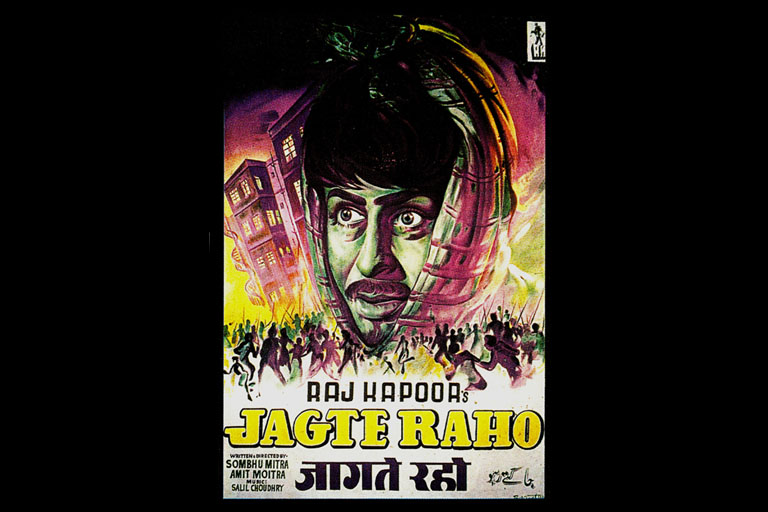

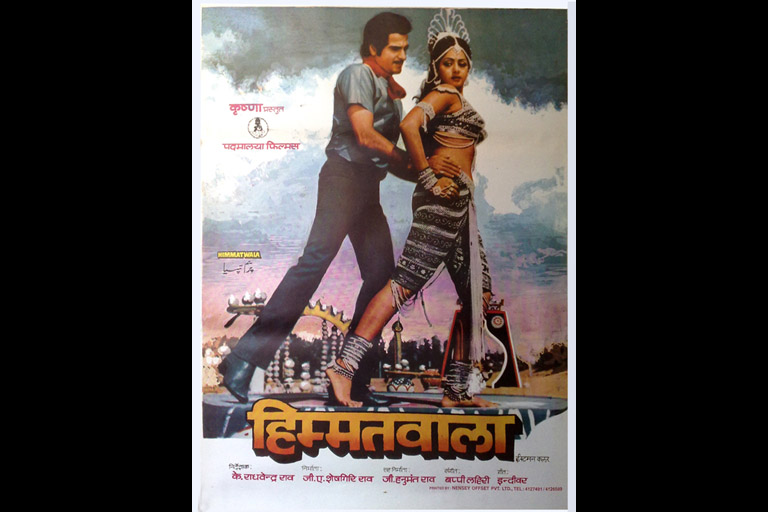

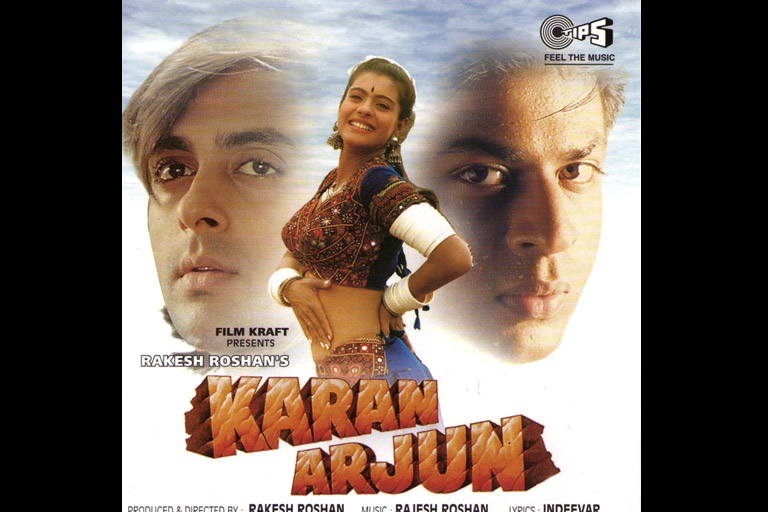

The thing with Hindi cinema, especially of the formulaic kind, is that it has a tradition of expressing the essential realities of society, even if they are depicted unrealistically. Look at its tropes. The hero, who is poor, gets exploited in the village by an upper caste landlord or a moneylender, he comes to the city where he is exploited further, he works hard but is cheated by the powerful capitalist or his goons, he is morally corrupted, rises to take his revenge and meets his absolution either in death or in reformation. Rural unemployment, poverty, migration to the city, poor urban living conditions, caste, discrimination, inequality and the unfairness of ‘the system’: there is hardly any important social or political truth that is left outside the pale of the typical formula. Its depiction may evoke derision but there can hardly be any debate about the fact that its content is fundamentally real to our society. This tradition, from Himmatwala to Karan Arjun, has never been recognized as being deeply political but can we deny it that status?

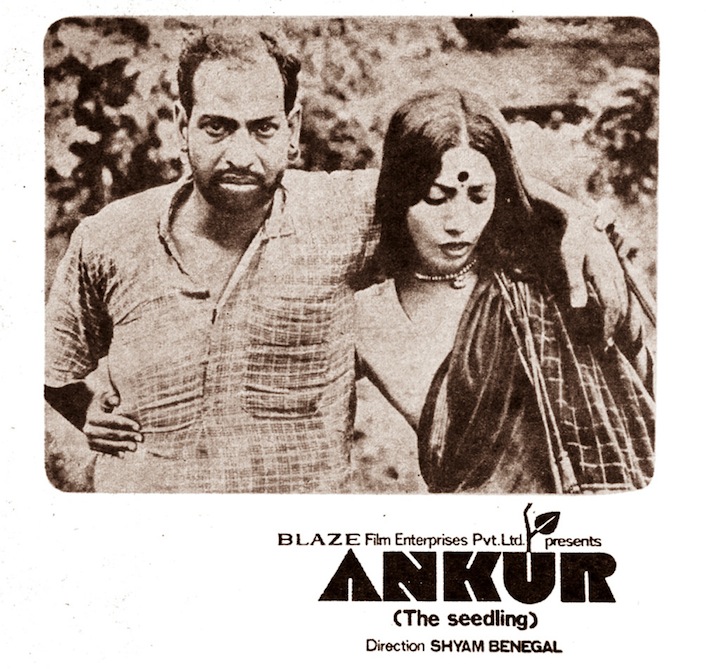

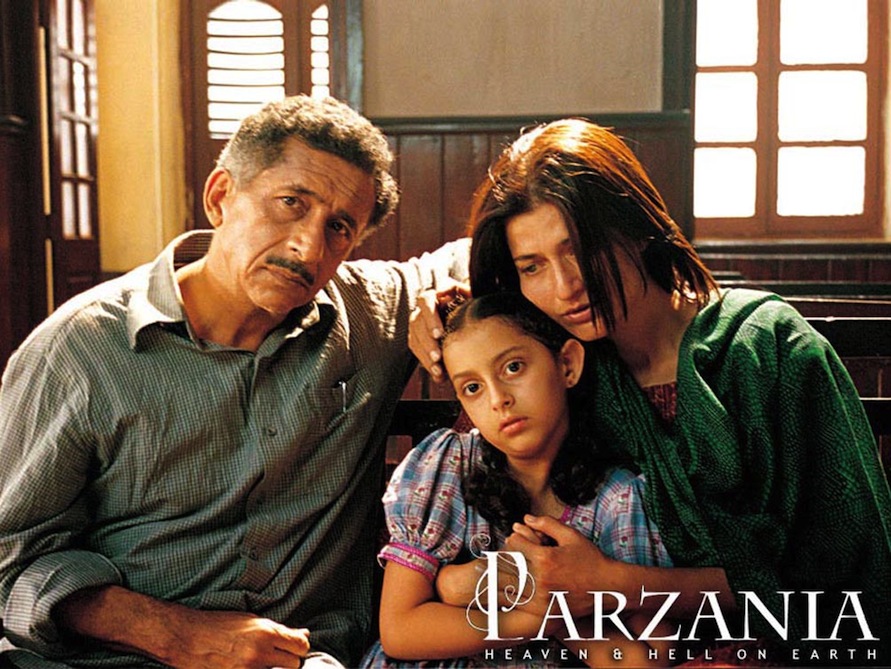

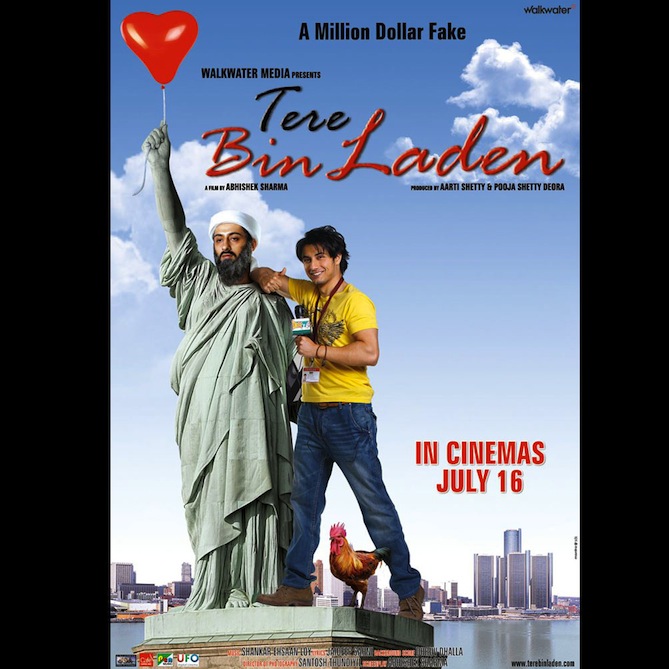

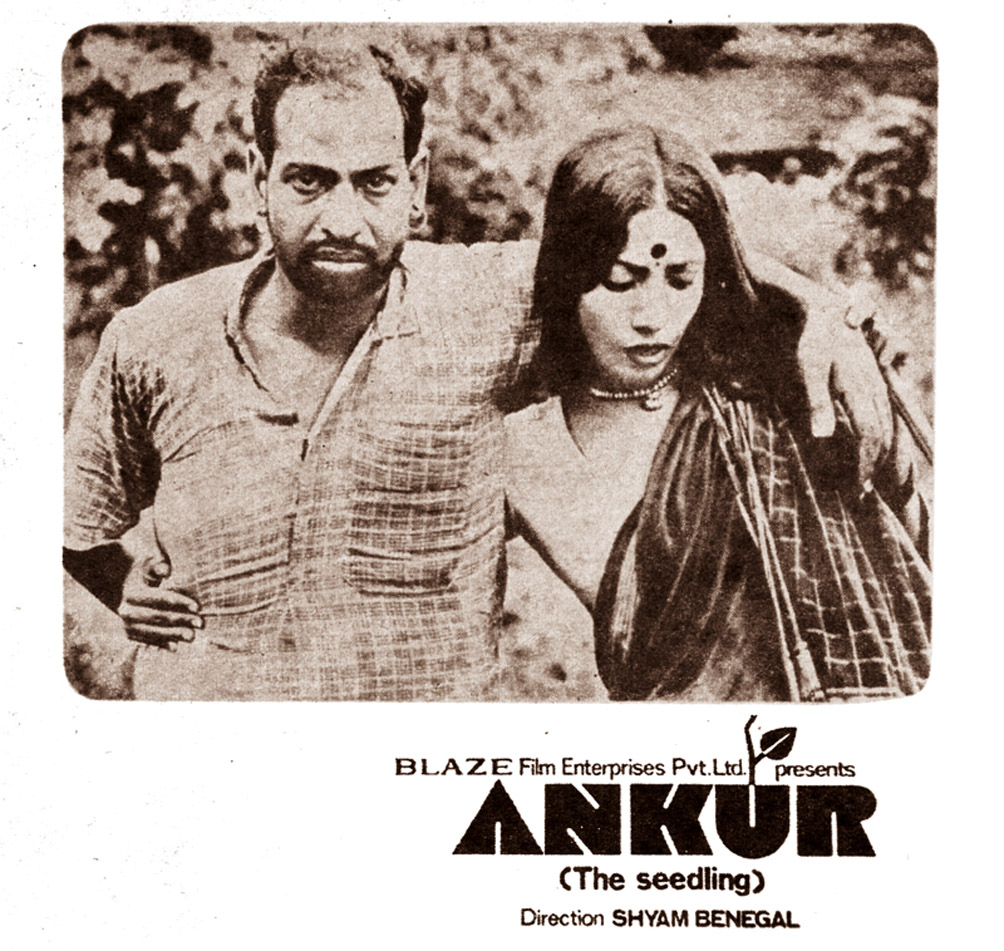

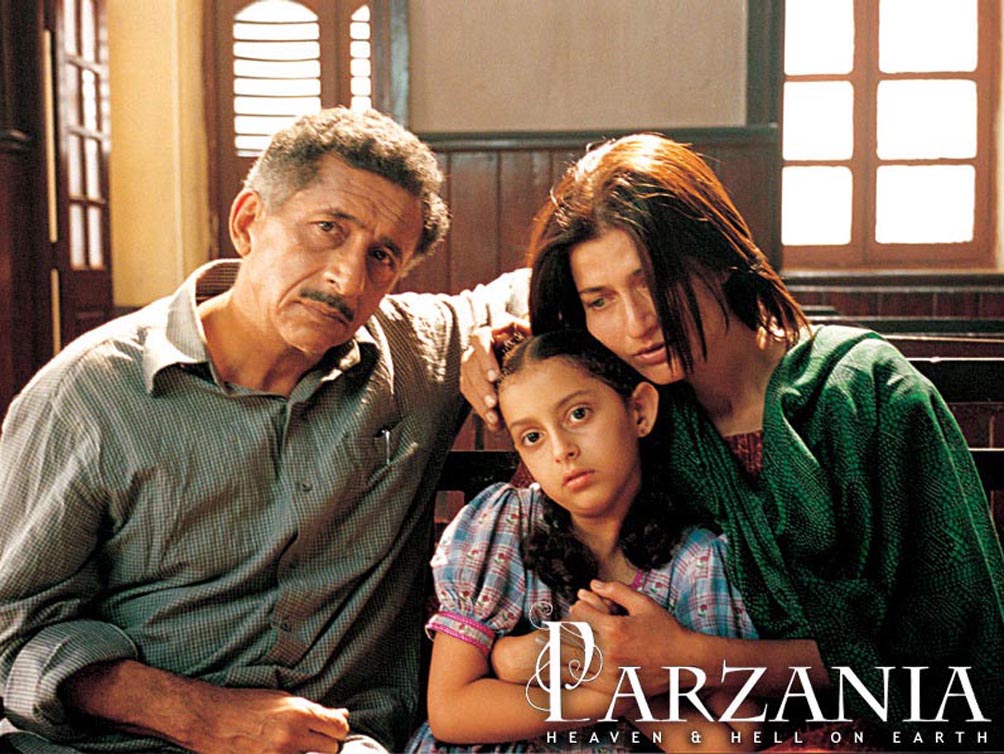

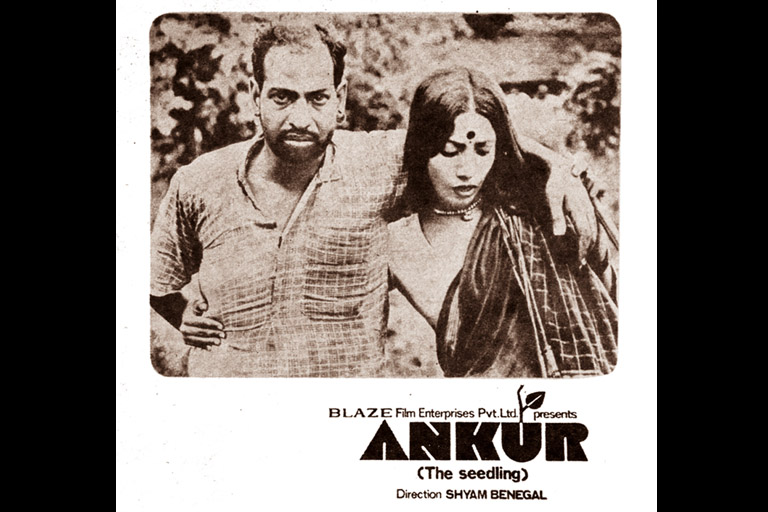

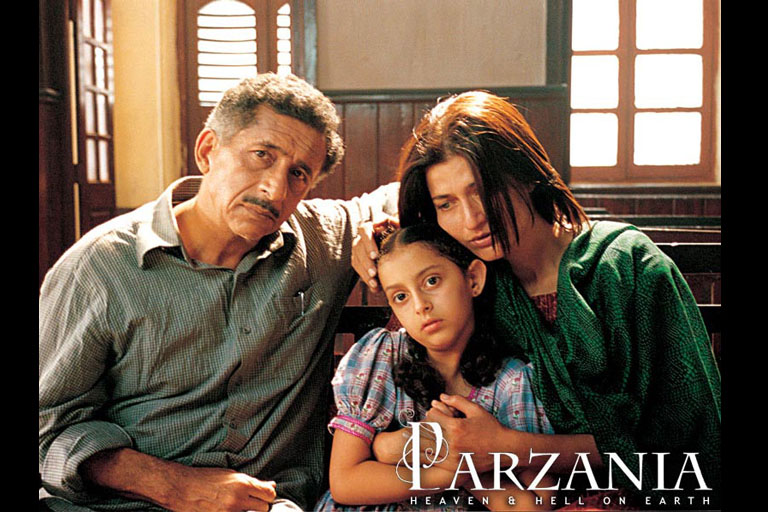

If political cinema is taken to mean the depiction of political intricacy accurately and mimetically then I will have to concede that formula did not care much about that, despite the essential realities it depicted. With the arrival of the New Wave in the seventies we moved to an era of the self-consciously respectable political film. Films like Ankur, Aghaat, Manthan, Aakrosh and Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro are authentic bourgeois political films. By this I mean films that emerged from an educated middle class and broadly left sensibility and films which tried to depict the ‘social forces’, as understood in Marxian terms, behind the human exploitation. Their main consumers too came from the same class. These were films that emerged out of an education in world cinema (before the term was invented) at film institutes. These films emerged from a closely knit community of filmmakers, writers and critics and were played to an intelligentsia that was organic and relatively unified. That consensus has broken down today. The changes taking place in India still remain the same as was shown in the films mentioned above but the audience that empathized with the downtrodden has been radically transformed. We have had political films of this kind in our times too: films like Firaaq, Tere Bin Laden and Parzania engaged seriously with some of the most important issues of our times. But in a scenario where the Congress party, which rules us, is Mukesh Ambani’s dukaan (as he said in the Radia tapes) and he or his ilk are today the leading financiers and distributors of cinema, a deeply political film stating a deeply uncomfortable truth, also perhaps a more specific truth that might directly indict someone, is unlikely to emerge.

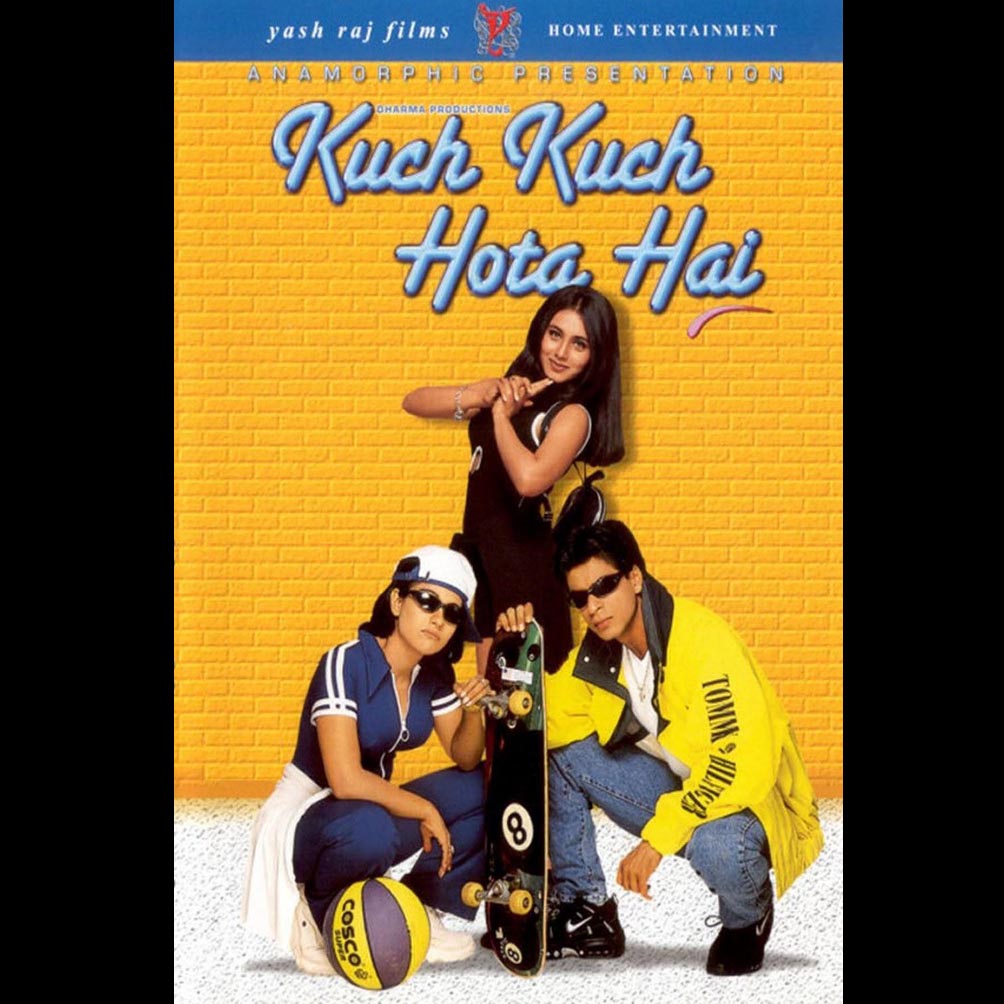

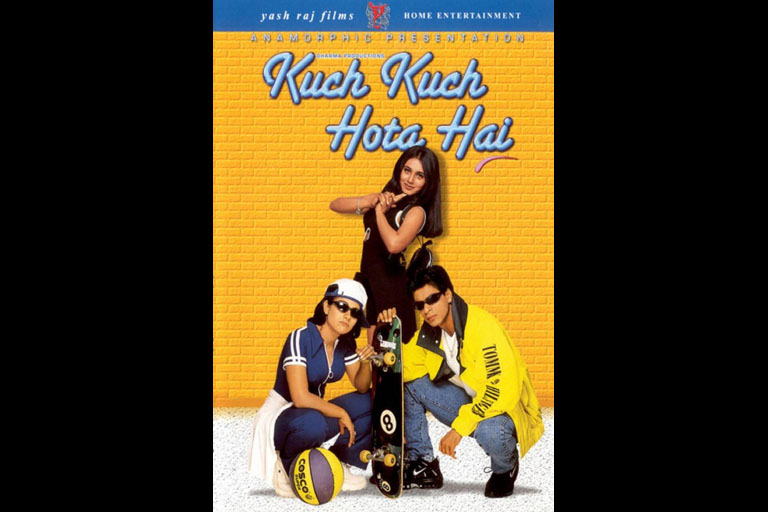

Sure, Hindi/Urdu cinema has seemingly opened up like never before. A greater variety of films is coming out of Bombay than was the case a decade or two decades ago and many a times films are succeeding purely on content. From a filmmakers point of view this is a very healthy trend because it frees us all from the tyranny of stars. However, like the Jawaharlal Nehru Urban Renewal Mission, the new cinema renewal mission has run into a morass of restrictions both from its production and consumption side. Like the rest of the country filmmakers too are deeply suspicious of and impatient with politics whereas politics is where the poor masses still acquire some importance. As the class basis of cinema, its makers and viewers, has narrowed, so has the process of social mobility in terms of who gets to make films. It is difficult to rise from the lines and become a director or a producer unless you are chic enough to become an assistant to one of the top studios or studio like companies. For that you need a good degree, preferably from Delhi or abroad. No Mehboob Khan is today likely to rise from a projector boy to a legend. The film industry, today, is a hereditary profession (like business or politics) and the educated middle class is desirous of turning it into a respectable enterprise. And none of them are really interested in the masses. For them ‘masses’ is the new middle class. But can there be a political cinema without the actual masses?

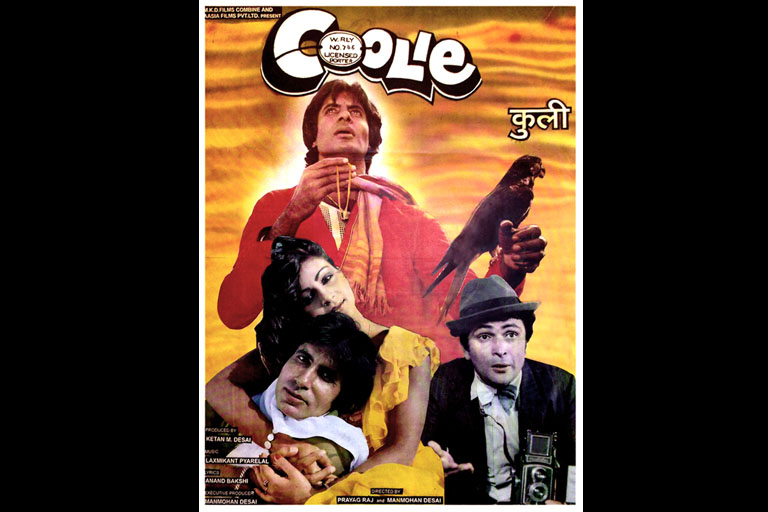

Until about 20 years ago, in a deeply hierarchical country, cinema was one true mass medium. Today’s cinema and the cinema halls where films are shown have excluded the masses. Cinema becomes political, not just because of its content, but also by whom it chooses to address. The formula films of Mithun Chakraborty are to me much more political by both yardsticks than anything we are producing today. Maybe I am an old man who is afraid of the new but I have jostled with the crowds and braved police lathis to get a first class (front row) ticket for Namak Halaal which, even if tangentially, depicted peasants and was watched by newly urbanized peasants. In a primarily peasant society, the peasant today is beyond the pale of our cinema and our cinema halls. Whither Political Cinema without the masses!

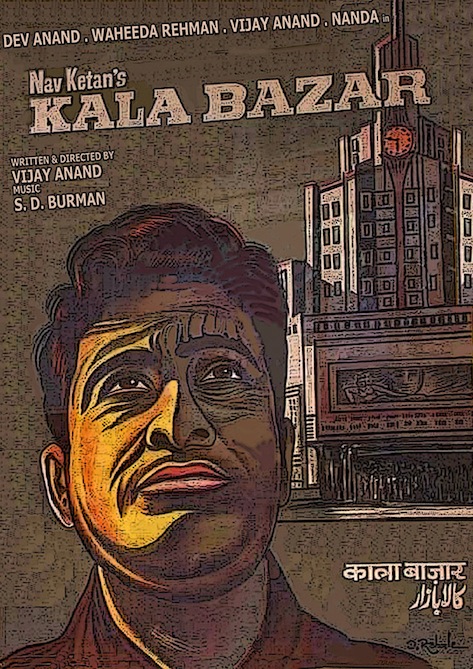

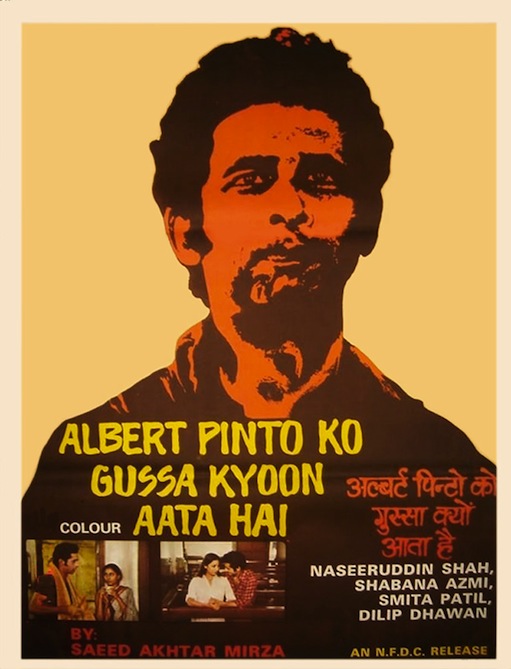

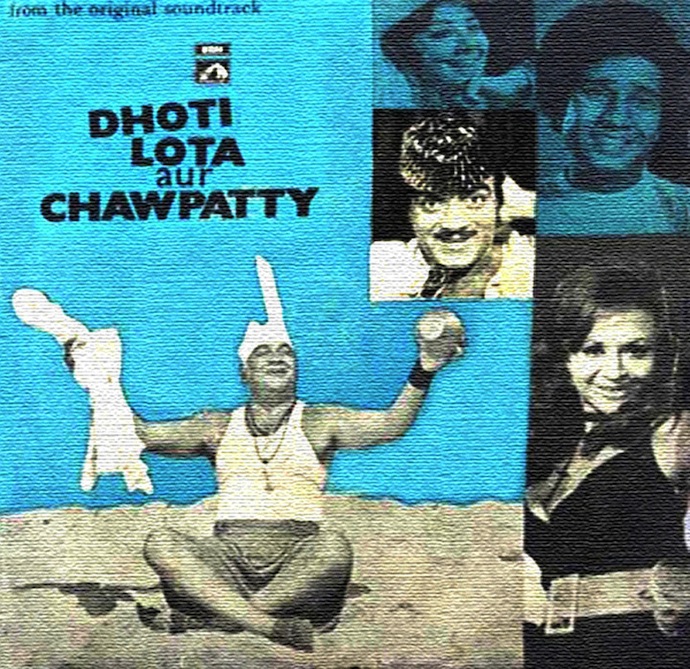

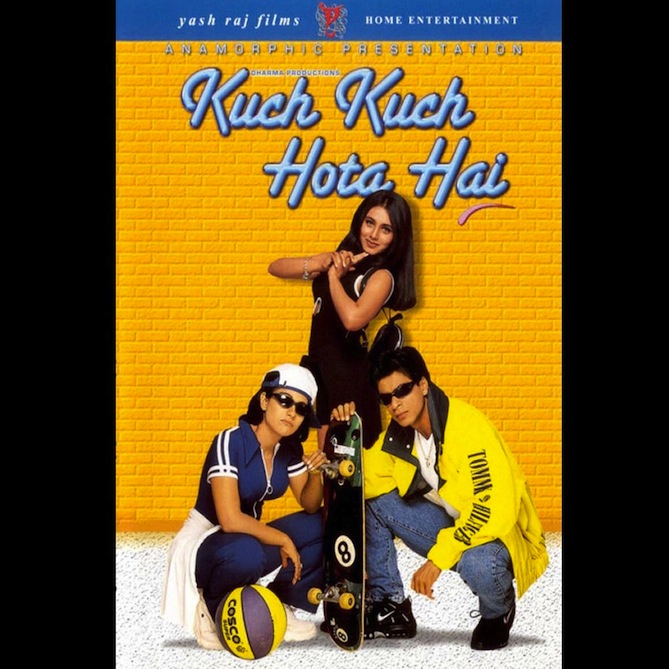

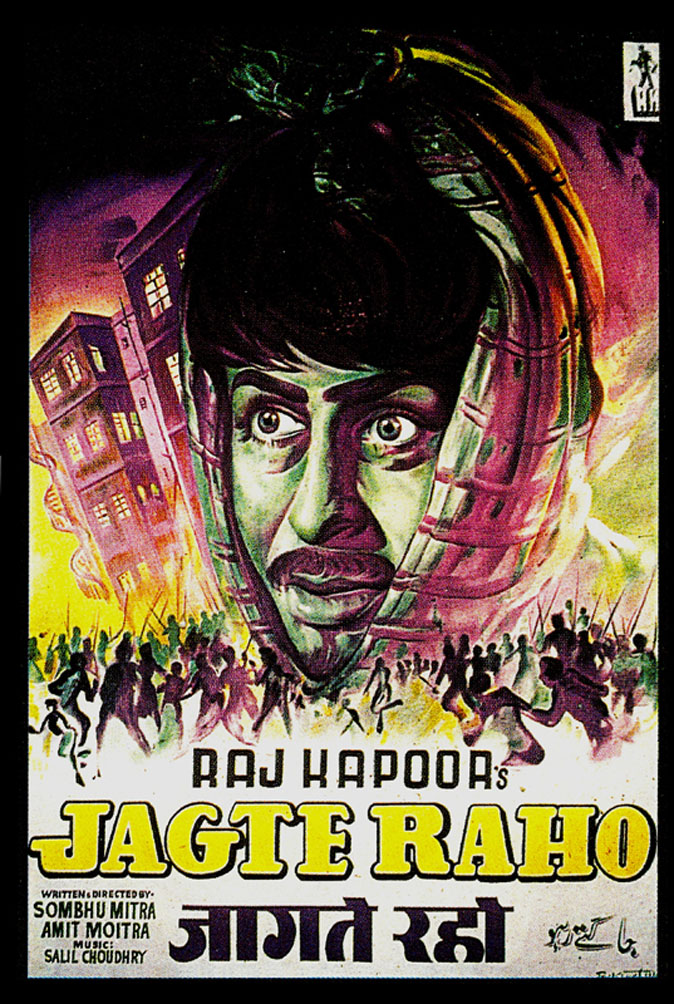

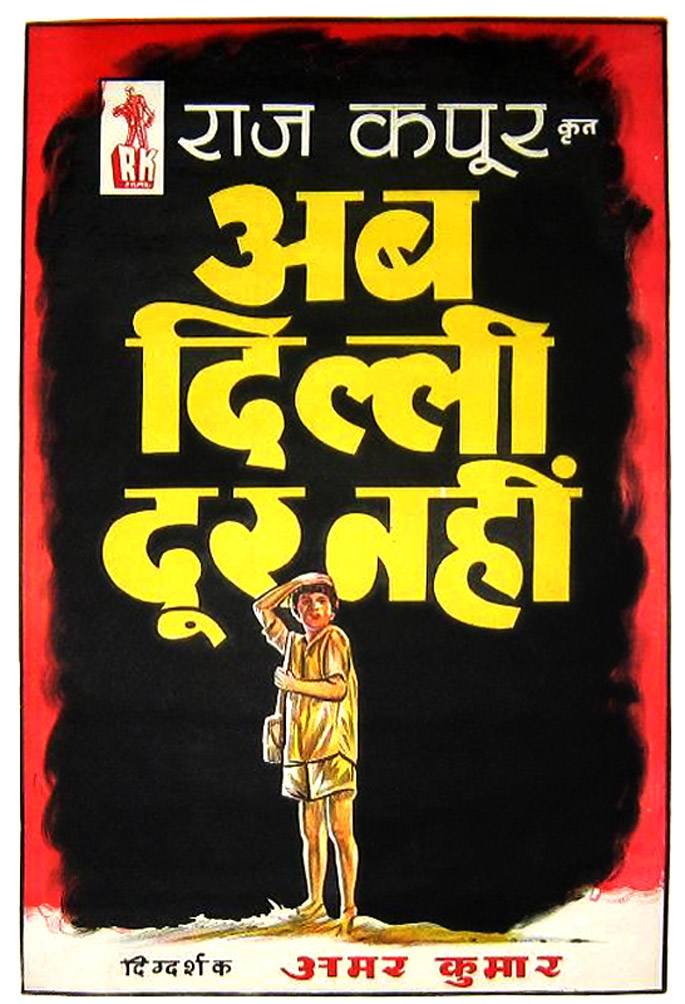

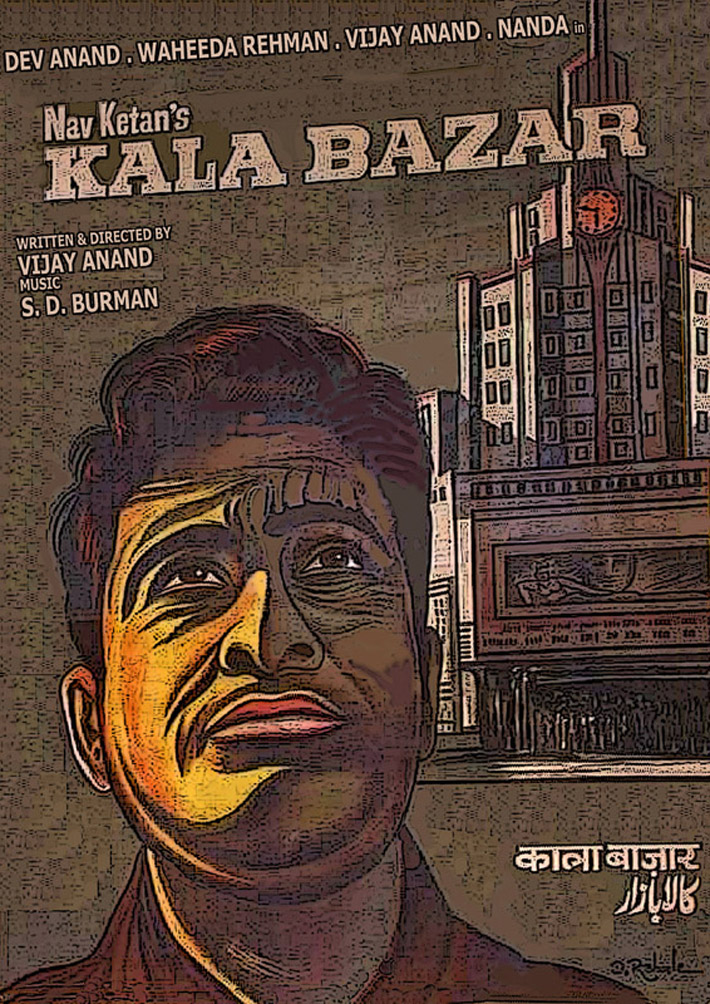

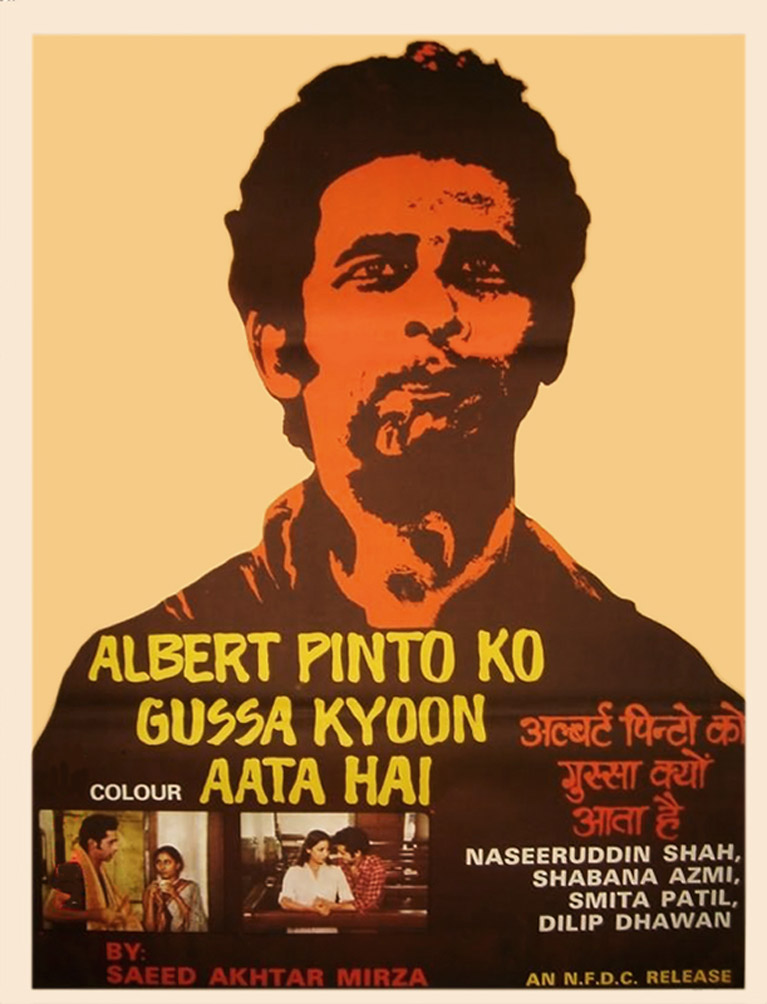

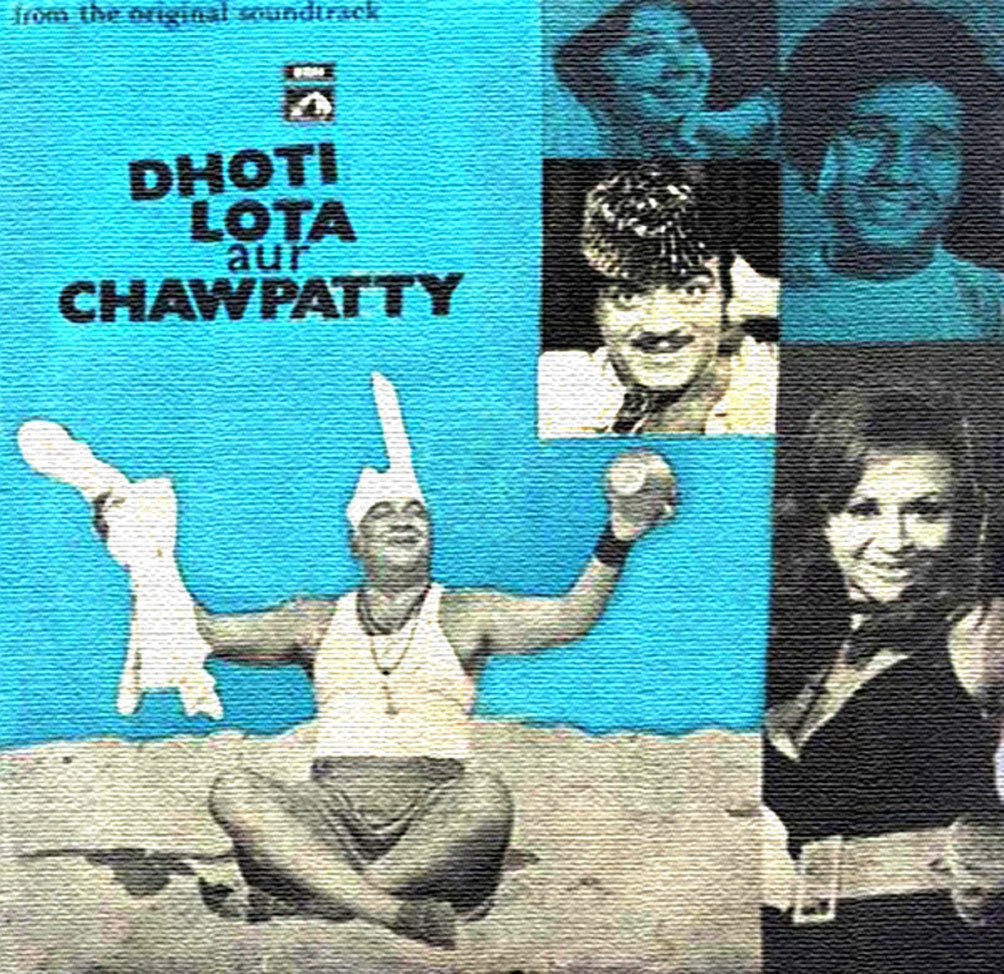

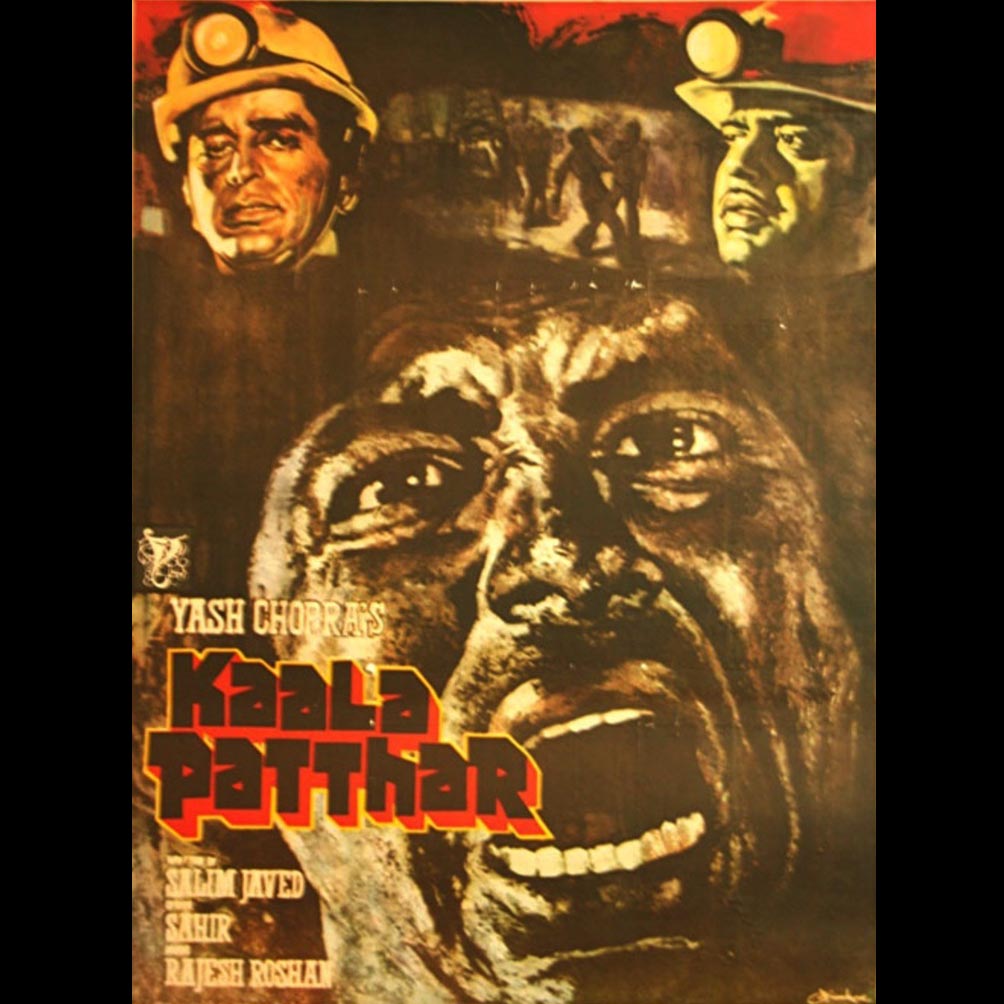

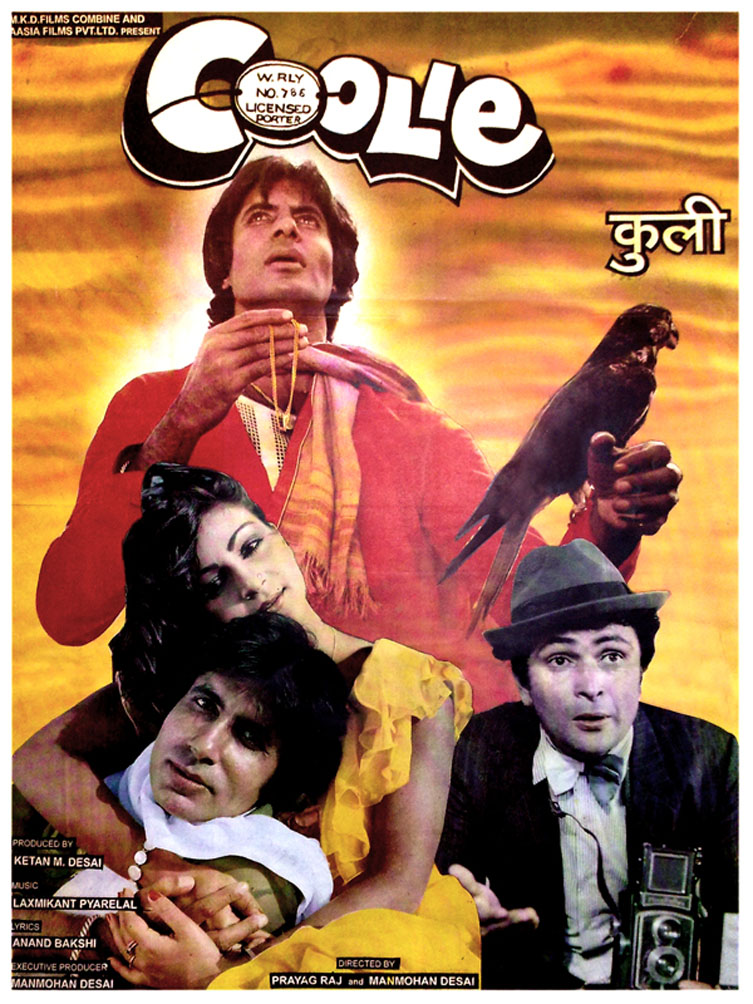

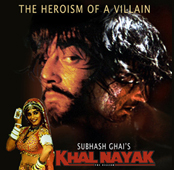

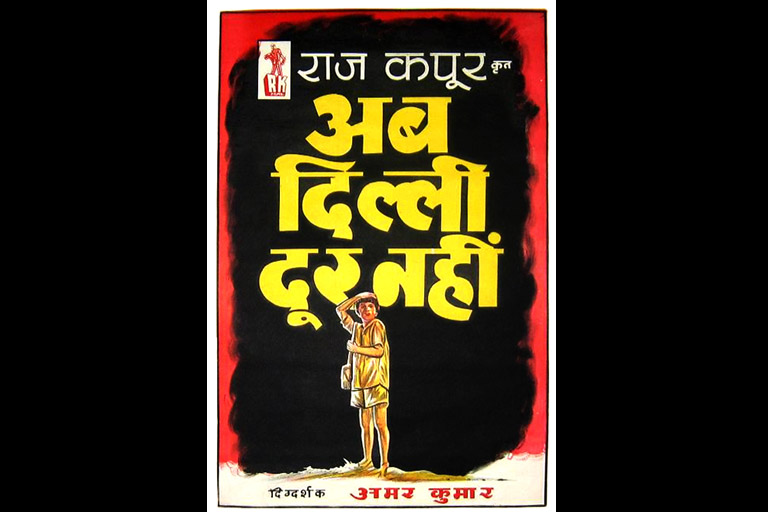

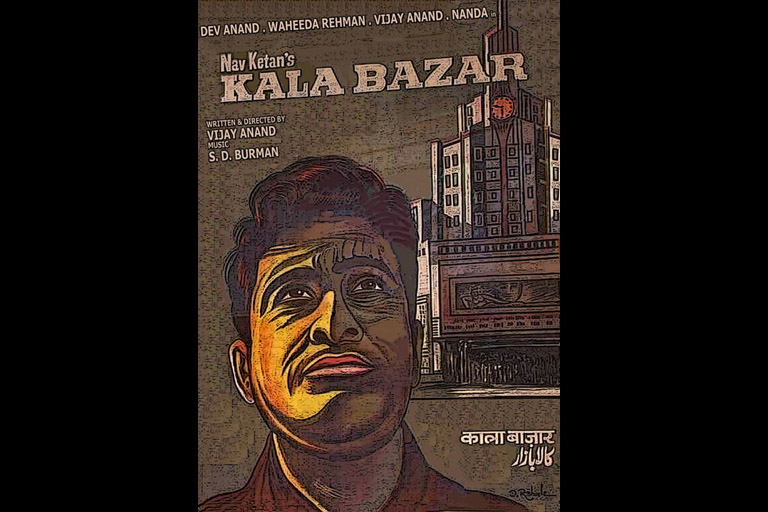

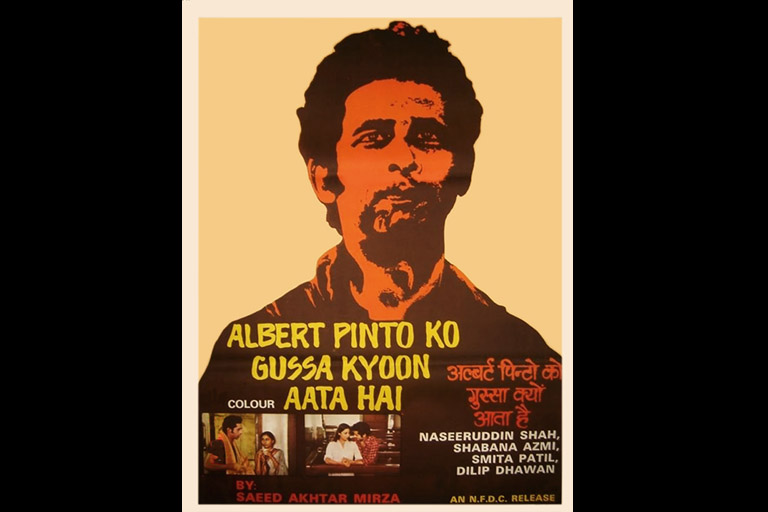

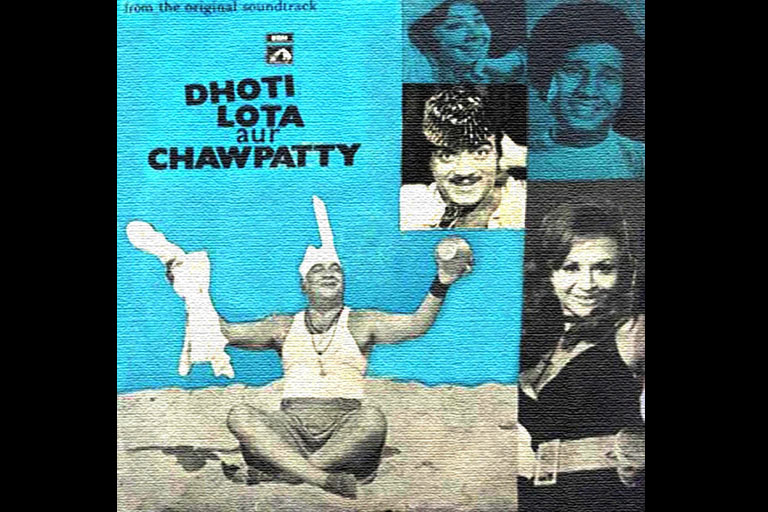

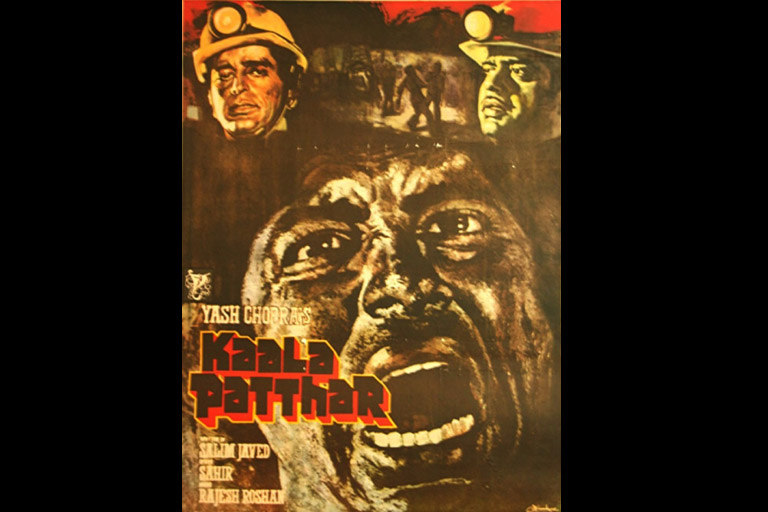

(In The Gallery: The politics of Hindi cinema through the years. Posters from the private collection of film historian S.M.M. Ausaja)

The Others

OpinionSeptember 2012

By Mahmood Farooqui

By Mahmood Farooqui

Mahmood Farooqui is a historian and Rhodes scholar. His first book Besieged: Voices From Delhi 1857 (Penguin) is a record of the Mutiny Papers, documents which provide sub altern perspectives on the siege of Delhi during the 1857 uprising. He has also worked as a researcher on William Dalrymple's historical narrative The Last Mughal. Farooqui has revived the ancient art of storytelling Dastangoi and performs it for a present day audience. Along with his wife, Anusha Rizvi, he has co-directed a feature film called Peepli Live.