-

Amrita Bagchi for TBIP

Amrita Bagchi for TBIP -

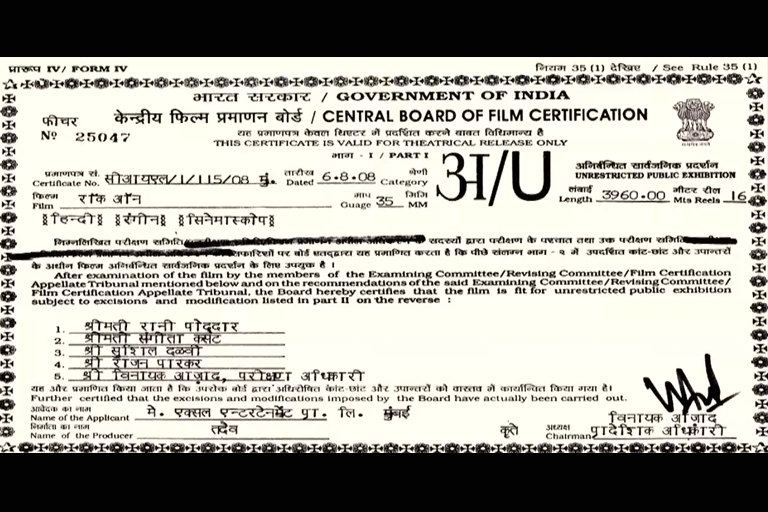

'U' certificate - Unrestricted Public Exhibition

'U' certificate - Unrestricted Public Exhibition -

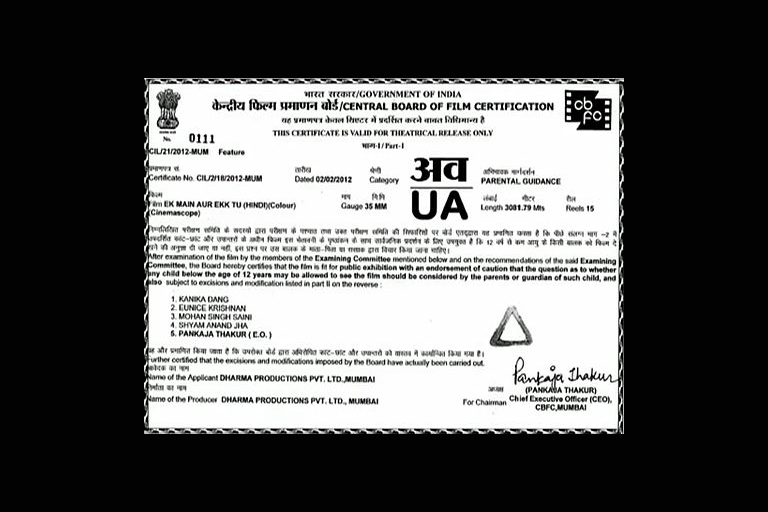

'UA' certificate - Unrestricted Public Exhibition - but with a word of caution that Parental discretion required for children below 12 years

'UA' certificate - Unrestricted Public Exhibition - but with a word of caution that Parental discretion required for children below 12 years -

'A' certificate - Restricted to adults

'A' certificate - Restricted to adults

Lawyer Lawrence Liang draws from key judgments, studies and interviews to argue that the I&B Ministry must re-look at the archaic law and guidelines for film certification through the lens of a ‘post-mediatized’ world.

Straightforward as it may seem the word ‘revisit’ can mean very different things for different people and this is particularly true when a minister says there is a need to revisit a law. In light of the controversy over Vishwaroopam, which saw a tussle between the central government and the Tamil Nadu government over the release of the film, the Minister for Information and Broadcasting (I&B) Manish Tewari suggested that there was a need to revisit the Cinematograph Act. “Time-cinematographic act revisited to ensure implementational integrity (of) certification decisions,” he tweeted, on January 31. “Otherwise each state would be its own censor (board).” Following this, on February 4, a committee has been set up by the I&B Ministry for this very purpose.

This would appear like a very welcome suggestion, particularly for those who have been demanding that we rethink the entire regime of film censorship altogether, except that the minister’s suggestion is qualified by a statement that it is important to revisit the Act to ensure that decisions of the censor board are implemented. All of a sudden the idea of revisiting the Cinematograph Act seems more sanguine than it initially did. It is also telling that the minister refers to the decisions of the censor board because the last time I checked we do not have a censor board in India, we merely have a board of film certification (the Central Board of Film Certification, or CBFC). That they do not merely certify films and do indeed act as censors is perhaps the precise need for revisiting the Cinematograph Act. In an ideal scenario revisiting the Act should mean doing away with film censorship altogether and putting in place a certification process much as in most parts of the world. In the unlikely event of that happening how may we best revisit the Cinematograph Act?

Unlike other forms of expression such as literature, cinema is distinguished by the fact that it remains one of the few instances in which it is not censorship but pre-censorship that is applied. If a book is published there is no need for the author to take anyone’s permission to release the book. This does not preclude the possibility that subsequent action may be taken against the book, but in the case of film even before it is released it has to go through the collective gaze of the CBFC, which determines whether it is fit for viewing by the general public. What justifies this differential treatment of cinema?

In 1965 filmmaker and writer K A Abbas filed a constitutional challenge against the pre-censorship of cinema arguing that this was in violation of freedom of speech and expression. Justice Hidayatullah in the Abbas decision (K A Abbas v. Union of India, 1970), which still holds as the prevailing law on the point, stated:

“It has been almost universally recognized that the treatment of motion pictures must be different from that of other forms of art and expression. This arises from the instant appeal of the motion picture, its versatility, realism (often surrealism), and its coordination of the visual and aural senses. The art of the cameraman, with trick photography, VistaVision and three-dimensional representation thrown in, has made the cinema picture more true to life than even the theatre or indeed any other form of representative art. The motion picture is able to stir up emotions more deeply than any other product of art. Its effect particularly on children and adolescents is very great since their immaturity makes them more willingly suspend their disbelief than mature men and women. They also remember the action in the picture and try to emulate or imitate what they have seen.”

The judgment advances what could be termed as the ‘medium specificity’ argument and this single paragraph has been cited ad nauseam in all subsequent decisions on film censorship. It will be worth our time to look at the various assumptions present in the paragraph a little closely, to see whether they still hold true in the post internet era. The paragraph suggest that the problem of cinema arises not so much from its inability to represent reality, as much as the fact that it is able to do it too effectively and that it has the ability to impact differential classes of people differently, especially children who are prone to believe whatever is happening as a result of their inability to distinguish between the illusion on the screen and reality.

A lot of the cinephobia that informs the law and judicial responses stems from an outdated idea of media impact which assumed that people had to be protected from the influence of media because of their incapacity to distinguish between reality and illusion. In the Indian context this attitude can be traced to a paternal and patronizing attitude of the colonial authorities who believed that native audiences were specially vulnerable to film on account of their relative immaturity and hence there was a need for greater censorship of cinema. The Indian Cinematograph Committee of 1928-29 conducted interviews across the length and breadth of colonial India to confirm their suspicion but were a little surprised by the results they encountered.

I will refer to just one interview with Lala Lajpat Rai— an interview from almost a hundred years ago worth ‘revisiting’ as we think of the Cinematograph Act of the 21st century.

“Q: Do you think that the cinema has any pernicious effects on the youth of our country?

A: No more than it has any effect in other countries. I have never heard of any particular complaint.

Q: One European gentleman who is in charge of the college youths in this province told us that there is a danger of the youths of this country being demoralized in their impressionable age on the undue emphasis that is laid on sexual films?

A: I do not agree with that view at all, and I will give you my reasons too. First of all, the influence of the cinema is no more and no greater than the influence of the novel or the drama. The college youths read a lot of novels, both American and European, and it is from their subjects of these novels, that most films are produced and I have no apprehension that the films are likely to be more harmful than the reading of novels and dramas. The fact is that the western civilization is spreading across the world. It has its good effects and its bad effects, and we cannot have the one without the other. I am sufficiently confident that our people will be able to resist the evil influences of the cinema on account of the general atmosphere of sexual morality that prevails in this country. Of course there will be a few individual people who may go astray here and there, but I don’t want to make that the basis of action.

Q: The point which is emphasized is that in some scenes nudity is prominent, and some of the films contain what they call close up scenes and, as my friend Col. Crawford puts it, cabaret scenes, under-world scenes. I mean that such scenes are made to appear so largely that they have a pernicious influence on our people. It is also said that such scenes tend to lower the esteem of the Western womanhood in the estimation of the people here.

A: I don’t want the youth of this country to be brought up in a nursery. They should know all these things, because they will be better able resist those things when they go out. They should see all those things here and they will be able to understand all the points of modern life.”

Lajpat Rai confidently asserts a vision of the future citizens of this country which does not condemn them into a state of perpetual infancy. He also refuses the theory of the specificity of cinema as an object of censorship and claims that the influence of cinema is no more and no less than that of literature. While the argument of the impact of cinema may even have had some partial truth at its inception, we have now lived with the medium for over a hundred years and we live in what may be termed a ‘post mediatized’ world where our senses are saturated with various forms of media and images from the television to billboards, and the internet and mobile phones.

Similarly the copycat theory that claims children copy every thing that they see in films has also been discredited. Shohini Ghosh, Professor Zakir Hussain Chair, at the AJK Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia, narrates an interesting incident about the Hindi television serial Shaktimaan which had run into controversy since it was claimed that it was motivating children to attempt to fly. Citing a telephonic interview with Mukesh Khanna, the actor who played Shaktimaan, Ghosh describes a particularly insightful moment when one child caller said: “Shaktimaan uncle, I want to be like you when I grow up. I want to be an actor.”

The courts in India, while responding to cases on film censorship, have often found themselves constrained by the archaic law and the vague guidelines that exist for film certification. Despite the limitations the courts have attempted to interpret the Cinematograph Act more liberally, to bring it up to date with social and technological changes, and it may be worthwhile for the government to take heed of some of these interpretations when they revisit the Cinematograph Act.

In the K A Abbas decision itself Justice Hidayatullah stated that the mere existence of themes which were listed as objectionable did not per se make them fall foul of the law and what was important was whether their “artistic merit or their social value overweighed their offending character”. Urging the officers of the Central Board of Film Censors (which was renamed the Central Board of Film Certification in 1983) to exercise caution in undertaking their task he said that: “Our standards must be so framed that we are not reduced to a level where the protection of the least capable and the most depraved amongst us determines what the morally healthy cannot view or read. The standards that we set for our censors must make a substantial allowance in favour of freedom thus leaving a vast area for creative art to interpret life and society with some of its foibles along with what is good”.

Similarly in the Tamas case (Ramesh v. Union of India, 1988) the Supreme Court affirmed Justice Vivian Bose’s observation that “the effect of the words must be judged from the standards of reasonable, strong minded, firm and courageous men, and not those of weak and vacillating minds, nor of those who scent danger in every hostile point of view” (Bhagwati Charan Shukla v. Provincial Government, 1947). In one of the most important cases on film censorship—the Bandit Queen case (Bobby Art International v. Om Pal Singh Hoon, 1996)—the Supreme Court allowed for frontal nudity on the basis that it was indeed an integral part of the film. They held that as the guidelines for film certification are broad standards and cannot be read as one would read a statute and within the breadth of their parameters, the certification authorities have discretion to ensure that they do not do away with what needs to be seen.

Let’s therefore welcome Manish Tewari’s suggestion to revisit the Cinematograph Act but let us also hope that it is not just an exercise in strengthening the powers of the central government vis-a-vis state governments, but a complete rethinking of the foundational presumptions that inform film censorship and their relevance in the era of the internet.

Contributor Image by Joi Ito (CC-BY-2.0)

The Heart of Censorship

OpinionMarch 2013

By Lawrence Liang

By Lawrence Liang

Lawrence Liang is a lawyer and writer at the Alternative Law Forum. He is currently finishing a book on law, justice and cinema in India.