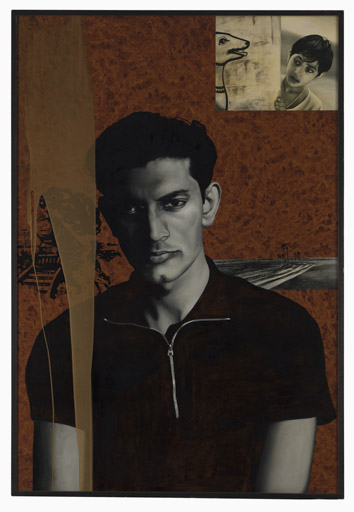

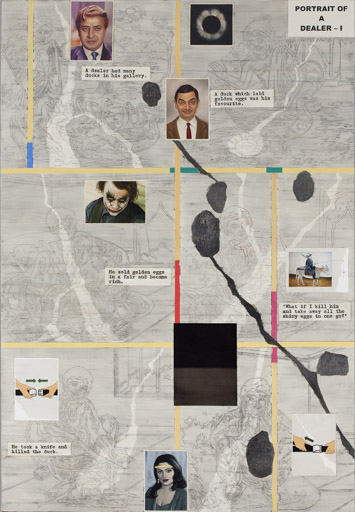

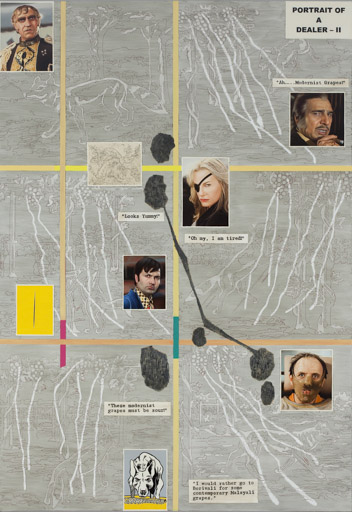

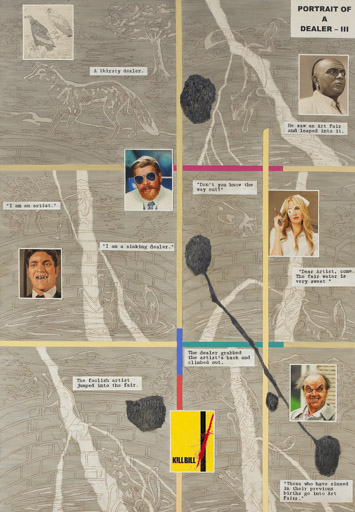

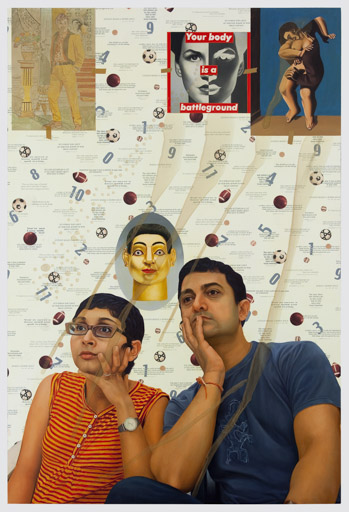

54 year old artist Atul Dodiya was, in 1977, in a fix as to whether he should pursue art or films because “they were both intense passions”. He chose art. The boy who was “brought up on old Guru Dutt movies” studied at the Sir J. J. School of Art, Mumbai, and the École Des Beaux Arts, Paris. He went on to win the Sanskriti Award, the Sotheby’s Prize for Contemporary Indian Art and the Raza Award. Among his acclaimed work has been his series on Mahatma Gandhi and one titled Bombay: Labyrinth / Laboratory. But his love of cinema persisted and continues to do so. A sort of self-portrait called ‘The Bombay Buccaneer’, an oil, acrylic and wood on canvas that marked a step away from his earlier photo-realistic approach in 1994, is actually a take on the poster of the Hindi film Baazigar. ‘Gabbar on Gamboge’ is a portrait of actor Amjad Khan’s character from Sholay. In ‘The Trans-Siberian Express for Kajal’ he painted the last shot—of a son perched on a father’s shoulders—from Satyajit Ray’s Apur Sansar (released the year Dodiya was born). ‘Sunday Morning, Marine Drive’ comprised, among other images, an angry young Amitabh Bachchan. Saptapadi is a series featuring actresses from regional and Hindi films, in a sort of commentary on marriage. Portrait of a Dealer features, alongside characters from Bollywood, Heath Ledger as The Dark Knight’s Joker, Daryl Hannah as Elle Driver from Kill Bill and Anthony Hopkin’s chilling Dr. Hannibal Lecter.

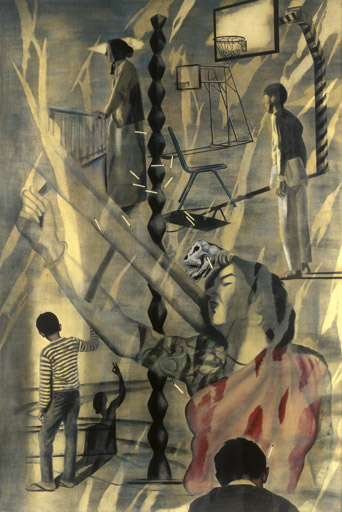

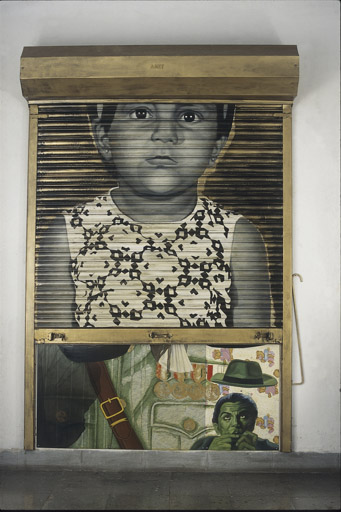

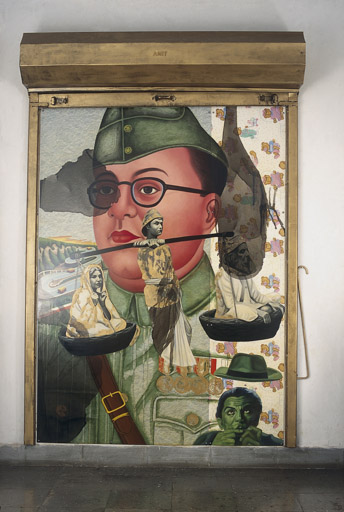

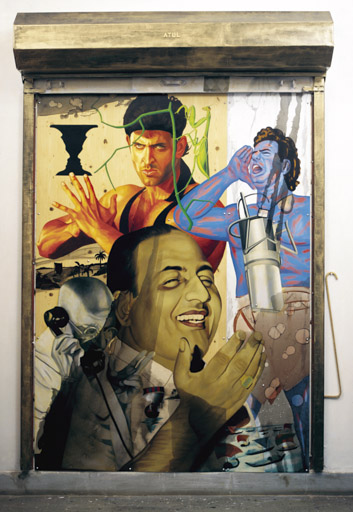

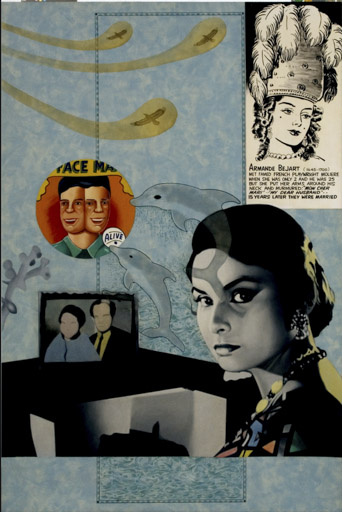

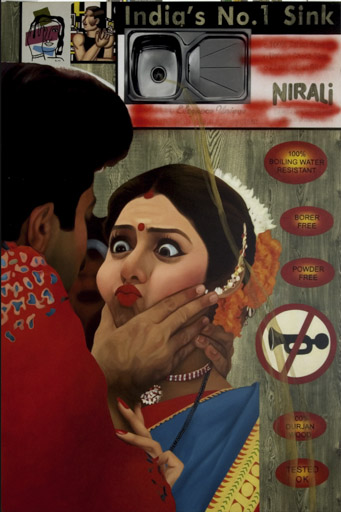

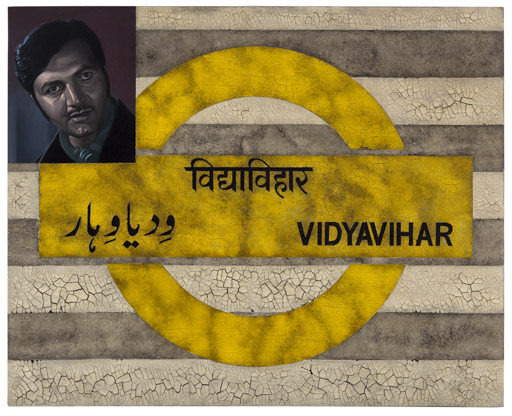

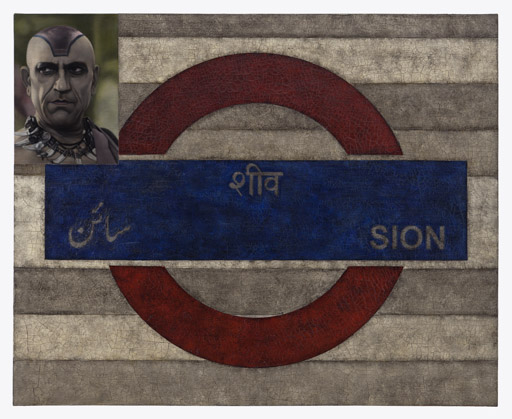

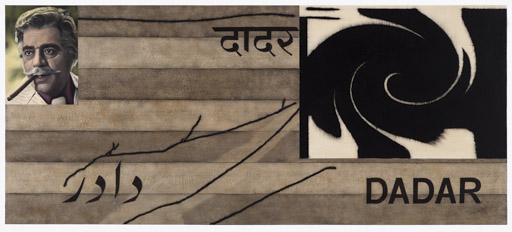

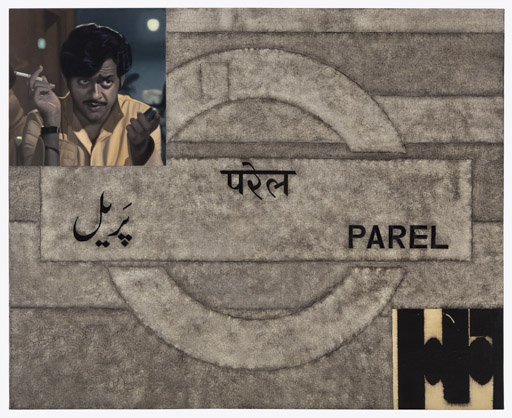

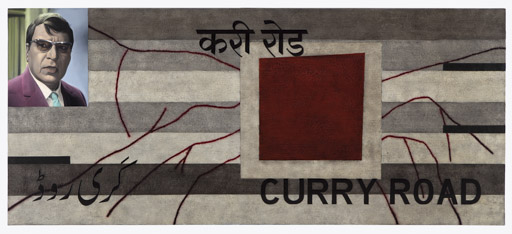

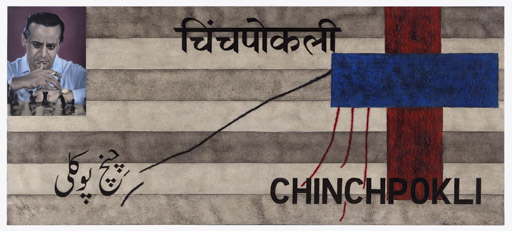

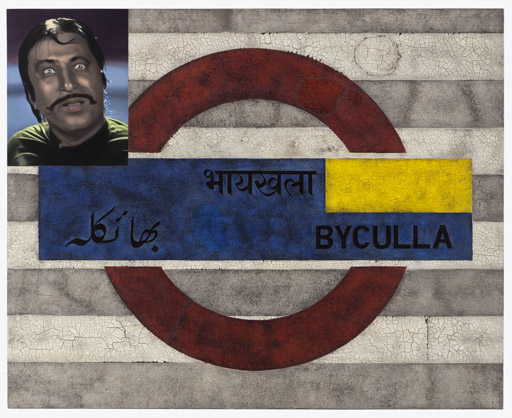

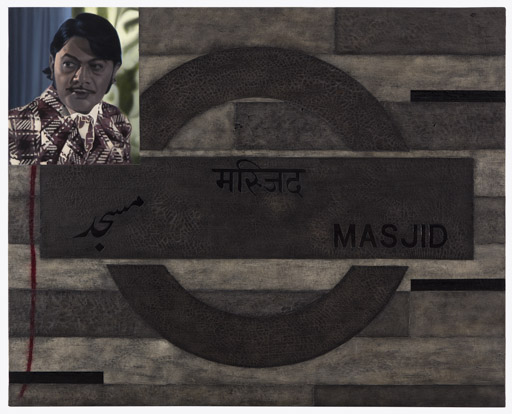

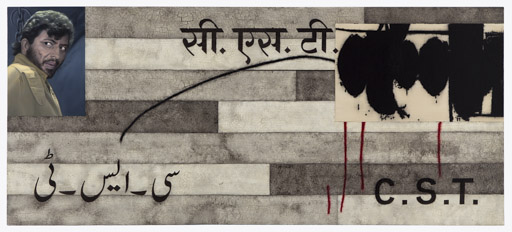

In keeping with this penchant for referencing and retaining cinematic images, Dodiya’s latest tribute to cinema (a part of the multi-disciplinary project Cinema City— that addresses the relationship between Mumbai and its film industry) has been on Bollywood antagonists, where he juxtaposes iconic old Hindi film villains against signboards for railway stations on the city’s Central Line, which he used to travel on when he went to art school. Ghatkopar, where Dodiya grew up and where his studio is still, has been assigned Pran, his own favourite villain. There is an anomaly in the series. Bindu, the only female antagonist in the series, is juxtaposed against ‘Atul’, a station that is actually not on the Central Line, but somewhere near Gujarat.

Back in Ghatkopar, he lets us into his studio, close to the chawl where he grew up, and settles down amidst scores of stunning collected and created works of art, to talk about his work and cinema’s imprint on it.

An edited transcript:

So before you went to the Sir J. J. School of Art, there was a moment you were considering studying Cinema. Now, you clearly love the movies, ample proof everywhere. You have also called it the ‘complete medium’, quite often. What tilted the scale in favour of studying Art over studying Cinema at that point?

Well, I was very good at drawing and painting and it was very easy to take a paper and start drawing on your small desk. So, I think one of the reasons was that painting was accessible. And I immediately realized… I was looking at lots of movies, and soon I realized that it’s teamwork, you work with many people. And there are instruments, and there are technologies, and there’s chemistry which is involved. And those things— I was a little scared of that. And then I was also aware that it’s an expensive medium, so even to take a simple photograph, you need a camera and, in those days, of course, film was there. So you have to get film, and get it developed and all that. So, in that sense, the painting was the most sort of ‘at hand’ thing. That I can just buy a small notebook and start drawing with a pencil, it was that easy. And I was good at painting also, of course. That’s why I am a painter.

Even possibly, at 11 or 12, you started to think of taking up painting as a career. You grew up in Bombay, in Ghatkopar… It’s interesting to me to try and understand where you were growing up. Was this an option back then? Did too many kids think of becoming a painter, or becoming a writer, or was it a very unconventional choice? Did it come from someone in your family?

No, actually, it was unconventional. It wasn’t easy, even for me. Though my parents were very supportive, but my elder sister insisted that I should go do Architecture, and she insisted that I should take in my 11 standard, instead of History, Geography, and Civics— Maths, Physics, and Chemistry. And I failed twice in my SSC (Secondary School Certificate) due to that. Of course, during those two years, I did a lot of painting, and my father gave me a first class pass, you know, a railway train pass, to go from Ghatkopar to VT (Victoria Terminus, now Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus) so I could have a look at the exhibitions at the Jehangir Art Gallery. The fear was that there is no future in this. There is no one star. At the most you can be a drawing teacher or have the job of a professor in some art school, but otherwise, what about the future, surviving, all those things? So, even the neighbours or relatives would encourage that point, that— ‘Don’t allow him to do painting.’ But then I was so good and I was winning these competitions, awards, and prizes and they realized that there’s so much passion and love I have for painting. So, it was decided that I should be allowed. And, of course, when I failed twice in SSC it was decided that I’m a gone case, and that I should simply do what I really love. And then I joined Sir J.J. School of Art, and then, there, I was like a king— enjoying painting so much. That passion, you know, of those days, till today remains the same. It’s not that now I have achieved, got, everything. It’s not that. That anxiety, that joy, is still there.

That’s terrific. But coming back to art and cinema, other than the obvious what for you are the key similarities and differences between the two mediums. I mean, purely in terms of the expression of each, because obviously, logistically, they are completely different mediums. For example, what does art afford you that cinema would not be able to. And, vice versa. What could perhaps cinema have afforded you as an artist which art cannot?

Yeah, well there are two things. As far as art or painting is concerned, it’s like a one-man-activity in your private space. Andthere’s total freedom. Whatever I want to do. Of course, there are viewers, there are people who look at your work, and your past, and your future and there are a lot of constraints and pressure once you are out there as a professional, but otherwise, basically, essentially, total freedom is there. I don’t have to prove anything to anyone; I just do it for myself. I just do what I really want to do. And no one can dictate to me, guide me. I am not painting for someone so that’s how it starts. And in cinema, first of all, you need a huge amount of finance and someone who puts in that money expects some return and that’s how it starts. But otherwise, for me, cinema is a complete medium, no doubt about it. There are visuals, there are sounds, there’s performance, there’s music, so much to it. And there’s a time span involved in it. So it is something, which is, I think, one of the greatest mediums of the 20th century. And it engages you immediately. When a viewer goes to the cinema hall or a theatre, watching a movie, within a few minutes, he’s there, forgetting everything. So I think the medium has a profound quality.

You know, from what I understand of your body of work, I would say roughly there are two ways in which cinema has influenced your work. One is, what I would call the indirect influence, which is from watching cinema. You know the craft you have learnt from watching a filmmaker and what he has done with a movie and then translated it in to your own medium. But then that is invisible, indirect. And then there’s a direct influence, where you have referenced cinematic tropes or cinematic images in your artworks. So I want to start talking about the latter first. And my first question would be that, in a world populated with Bollywood images, which have been rehashed as kitschy cool—it has become a trend over the last decade or so—how do you stay inspired to reference Hindi cinema?

Yeah, I mean, see from early days, from when I was born and brought up, here in Ghatkopar actually, the movies were always here. You know, one of my first experiences of… if I have to say which are the first paintings that I saw… One kind would be at home— the earlier images of gods, goddesses, my mother being a very religious person. So they were all those calendars which used to come during Diwali, and they were framed, and they were all up there on the wall. And the second thing was, while going to town, I would see the huge hoardings, the painted ones. Nowadays, we have digitally created hoardings and posters of films. But in those days, there were a few studios where the hoardings or posters were hand painted. So that was my first exposure to art, I would say, or painted images. And I was, you know, quite astonished, quite sort of stunned to see those large, huge hoardings where the heroine is painted in very soft turquoise or emerald colours, and villains, often, with a palette knife, which has a texture. I still remember there was a film called Kuchche Dhaage. It was about the dacoits, with Kabir Bedi and Vinod Khanna—they were the dacoits—and the large heads were painted with a palette knife, with extreme orange and violet thrown on both the sides with green and red. So, you know, I still remember those things. And, would love to see all that. So, that’s how it started.

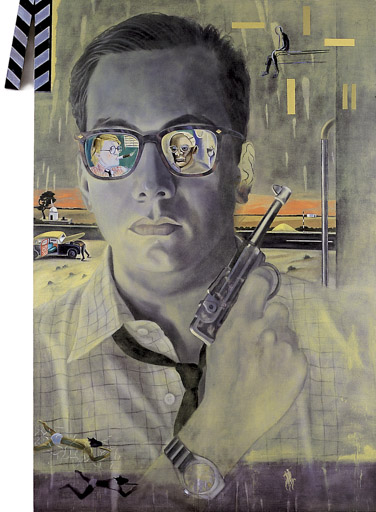

And I remember, like when, I was in my sixth standard, when I really, passionately began looking at art, drawing, and painting, I think Aradhana came, of Rajesh Khanna, and my God! It was, and it’s sad that last year he passed away, but it was phenomenal. I remember watching his movies, Rajesh Khanna’s films like Aradhana, Do Raaste, Anand and Amar Prem. I have five sisters, and four are elder to me, and they were all fans of Rajesh Khanna, like everyone else. And, to impress my sisters’ friends, all those girls, who used to come home, I would keep on drawing portraits of Rajesh Khanna, one after the other. From whatever magazines used to come at home, or the newspaper ads, so these things were there. And I think much later, when I started… ‘quotations’ and ‘reference’ was always a part of my work. I see all kinds of art and I get engaged with all those, from the early masters to Chinese calligraphy to contemporary art— whatever. And somehow, when I start doing my own work, I immediately, I am reminded of something, and if I am remembering some other artist’s image, I incorporate it. I allow it to be included in my painting. So that was happening—lots of it actually happened, mostly after ’91 or ’92, when I was a French government scholar in Paris and when I returned from Paris—and at one point, I thought: ‘Well, there’s a whole world out there, which I was probably interested in but ignoring in my own eye, which was the popular culture— the calendar art, the element of kitsch in popular art, which is so much a part of our life.’ Particularly if you are living in a suburb like Ghatkopar you are constantly bombarded with these kinds of images, during the festivals, like Diwali or the Ganesh festival. Images that I was not allowing in. And I remember one of the first paintings that I did then, which was called ‘The Bombay Buccaneer’, and it was about myself, holding the gun like in a James Bond pose, and the painting was inspired by a film called Baazigar, with Shah Rukh Khan and two actresses being depicted in his glasses. It was a newspaper ad that I kind of saw, and I did my own version of that depicting my two favourite painters in my glasses and after that I thought, ‘This I should allow’, more and more, and I was enjoying it actually. You know, when I paint a film star and then people recognize it, it’s already an established image, which I am kind of incorporating into my work. But, along with that, I would juxtapose things in such a way that it would create a different meaning all together, all the while retaining the personality of those film stars. For example, I wanted to do for a long time, this series of station signs, and when the Project Cinema City happened, I did this thing. And it’s obvious that cinema is there, and the city is also there. I wanted to create the villains of Bollywood, particularly of the sixties and late fifties, seventies. Now we have different kinds of villains but those were very, very stylized people in the way they would be depicted in those films.

I would interrupt you for a second; I want to talk about this series in some detail. I am going to come to it a little later. You know you said this, that you quote a lot in your work, so, you don’t need to necessarily have an answer to this question, but I would put it to you anyway. Why reference directly? See every art, every piece of writing, comes from somewhere— we are building upon the collective consciousness that we have, the artistic, or the mythological, or whateverthat is. So, invisibly, it’s there, in everything we create and everything we do, but why do you choose to make direct cinematic references in your work? Do you feel like it falls upon the artist to understand and interpret the enormous impact, the monumental impact, cinema has on our culture and psyche, or is there any other reason?

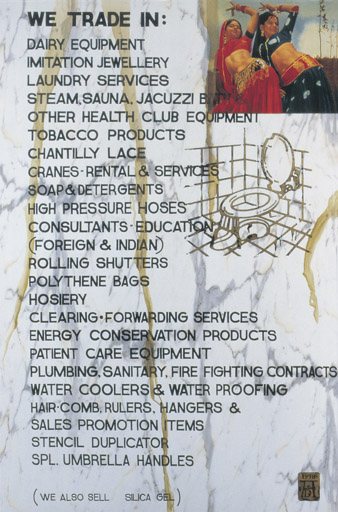

No, I think. Not because the cinema has this, as you said, monumental impact on our psyche. Not for that, but I think, some of the images or even… I often go to the actors whom I depict, whom I admire because I like them. And you know, what I do, as far as painting references are concerned—also the images which I do they are already established, already known—they are things which I like. So, what I used to do as a young boy is just copy a portrait of Van Gogh. You know, that’s how I started. My very first oil painting was a self portrait of Vincent Van Gogh which I attempted, so I think. And there was an immense joy, when I achieved the likeness of a Van Gogh painting in my painting, and I think, somewhere I retain that even today, that when I am coating complex paintings of mine, or maybe these cabinets that you see here, there are lots of Piet Mondrian abstract paintings inside. Actually I still have that same innocent approach— that ‘Oh! It’s so good, and I like it, and I did it for myself’. But of course, along with that, a lot of other things come, and then I noticed while doing that that though the established meaning is there, at the same time sometimes it also gets another meaning, when you put other elements together or juxtapose it with something else. So I think, basically, the images which came, particularly from cinema, they came because of the movies which I enjoy and the stills which are so popular, which people are familiar with. And I think one of the reasons is— the viewer matters to me a lot. You see, often artists are very private people, they just do it in the studio, what they want to do, and it gets exhibited. They are not, maybe for the right reason also, very concerned with how the other people would see it. They say it’s open— what one wants to see, let them see. But in my case, I am really concerned about how people see and how people don’t see a painting— particularly when you are living in a country like India, and a city like Bombay, a suburb like Ghatkopar, in a chawl. I have moved into this studio two to three years back, but where I was born and brought up, the same home in my chawl became my studio for more than 20 years. And, so my neighbours, they were my first viewer, they were the audience who would see me. They would have seen me drawing portraits of Rajesh Khanna as well as creating much more complex works with roller shutters and other stuff, so they were also getting educated with me. Because they were watching my paintings and I would love to share. I love to talk about what I am doing, why I am doing it, and in that context I think, I feel that I want to create something which one should be able to understand or which one should be able to relate to at least. So there are elements, whichare familiar and so the viewers are immediately drawn to those things and along with that I add many other things, which they are not familiar with sometimes.And that creates a sort of a conflict and they want to struggle to understand ‘why’. Why, for instance, do I have in one of my paintings, which is called ‘A Poem of Friends’, a Jayshree T. and an Aruna Irani dancing in a corner and otherwise it is full of text. And then there are two film stars dancing, so I think they immediately get drawn to it and then they try to understand what it all means. So I think how to get people engaged in my work has been my prior concern till today.

So, in a sense, you are saying that, for you, a lot of cinematic references come from a need to stay connected with your first viewers. You know, people who you grew up around. And in a sense also to stay connected with your own self. To start where you started and then take everything along as well but the other thing that I feel you express very well through cinematic references, that comes across really well, is your sense of humour. There’s a little bit of a tongue-in-cheek, there’s a little bit of a wry smile. Would you say that cinematic references are one of your primary, you know, sort of vehicles for a little bit of fun that you have?

Yeah, I think you are right. Whenever I have used particularly Bollywood and film stars or villains there’s been a lot of humour and wit, which is not to say that I am making fun of them, but I think there’s certainly humour in it, some element of tongue-in-cheek, those things are there. But then there are also other references I have from other cinema, like films of Satyajit Ray, (Federico) Fellini, or (Jean-Luc) Godard.

I was going to come to that. You are one of the artists that reference both commercial masala cinema as well as serious cinema. How is your approach to each of these references different?

Of course, the Hindi masala films or popular films were very much there. In Bombay it’s everywhere, at home also. And of course, the radio was very much there with Hindi film songs and the songs that we know from the forties, the fifties, the sixties… they were just amazing. The great musicians, the great singers, the great songwriters… the songs which I still hear. When I am painting, constantly, the songs of Mohammed Rafi and Geeta Dutt are constantly on my music system. But that is one thing. But I think when I saw other films, like regional films in India or not just Hollywood films from the United States but French cinema or German films or Italian films, then I felt that ‘Oh! This is also cinema. But this is so different’, and I must tell you a small… what happened to me when I saw my very first Satyajit Ray film on Doordarshan. It was on a Saturday. The movie was Nayak. And when I saw Nayak, the story goes like the film star is going to get an award in Delhi and he chooses to not fly, but to travel by train and the journalist Sharmila Tagore, the beautiful Sharmila Tagore in that film, they start talking and she wants to take an interview at some point. A station comes, the train stops just outside a small village near Calcutta, and he gets down just to stretch his arms and orders a cup of tea. And he takes in that small cup and as he is about to drink a cup of tea he sees that the journalist is sitting near the window and she’s looking at him. So he just asks in a gesture, whether she would like some, and she says, ‘No’, and that shot, you know, that changed my life, I would say.

What about that shot?

That was so natural, that was so real. I thought this is as if I was there. And it was not just a film; it was like life itself. I mean, this is the way people behave, this is the way people talk, this is the way people make gestures, and, I don’t know, it was probably… it was a kind of evening light, the tonality of the film, the expression of the actors, maybe the shot…whatever. I don’t even remember. Probably the subtitle. I don’t speak Bangla or understand it, but that was a huge impact. After that I had heard of Pather Panchali and the Apu Trilogy, but that was the first film (by Ray) that I saw. And I said this is something, a different kind of a film, and then I wanted to see more and more of that kind of film.

Coming back to your own work, can you tell us by examples how differently you would reference something from serious cinema that stayed with you? Like, if we take something from Charulata and something from popular cinema that you havegrown up listening to and watching, something as a part of all of our collective memories. If by example you could say how differently the references come to your work and what you do with your references, which is different in both the cases?

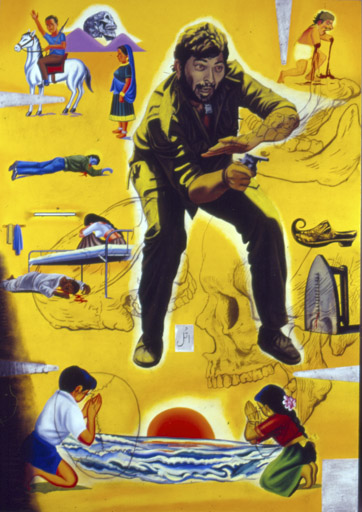

I think I will have to select the specific paintings. For example, in 1997, or ’95, I think, Sholay was celebrating its 25 years. I did a painting called ‘Gabbar on Gamboge’, which had a chrome yellow background— yellow gamboge. Amjad Khan as Gabbar Singh from Sholay. The story around him, narrated with violent imagery and the skulls, and bones, and other things around. But it was like a strong painting in terms of colour and sound. Like, if the painting is there, no one can miss it. Its brightness and the image was obvious. There I wanted to do this in a certain way. But before I did that painting, just the previous painting was called ‘The Trans Siberian Express for Kajal’, which was the last shot of Apu Trilogy or Apur Sansar, when the father ultimately goes to the boy and he takes him on his shoulders. And Soumitra Chatterjee is on a frontal face and some of the written text comes on screen. And that painting had to do with… the film was made in ’59, and I was born in ’59 and I painted it at the end of the century. And along with that there was another complex world; in fact, Joseph Beuys’ drawing books is here. And the artist Joseph Beuys, the major installation called the ‘The End of the Twentieth Century’, with large granite pieces lying in a gallery studio. I had put all of that in the background and I was just wondering how time has changed, even in art, the artwork was happening in a very different way. I mean, people were familiar with oil in canvas, and sculptures in bronze or marble, but lots of things changed in the last 25 to 30 years, so I was thinking about it and how I myself have changed in all these years. And, probably, the boy who’s there in that film, acting as Kajal, he must be around my age. Of course, a little elder. So I wanted to think about the time— the changing time, and how life gets changed and how in the film that man’s wife suddenly dies during the childbirth and how his life changes. We know the whole story about that particular film, Apur Sansar. So it was a very brown, sepia-tone picture, with imagery from Satyajit Ray’s cinema and the images from Joseph Beuys— the German artist’s works. Each came from absolutely separate kinds of areas. So, that was a different kind of film, but ‘Gabbar on Gamboge’… I enjoyed Sholay a lot. I saw it first day, first show, I remember, ’75, I think. And I saw it at Basant theatre in Chembur. It was a long film and I remember in the interval, people were talking about how Amitabh Bachchan and Dharmendra, they are fantastic, and Sanjeev Kumar, of course, he is a great actor, but the villain, why, they should have gone for some well known name. And I had gone for the film with my cousin and I was telling him, I think, someone called Amjad Khan— he’s the high point of this movie, he’s going to be a fantastic actor in future, and that’s what happened. So, I remember that. So, I think probably with a popular film like Sholay, and of course we know how popular that film was…

So I think, it was in ’97 when India was celebrating 50 years of its independence and many events were happening. So when I painted ‘Trans Siberian Express for Kajal’ I was asked in Bombay for a show and I said I am going to depict one artist, whom I admire and for that I went to Satyajit Ray’s film. And ‘Gabbar on Gamboge’ was shown in an exhibition in Delhi in the National Gallery of Modern Art, and it was about choosing something from popular cinema. And then I thought of doing something from Sholay and that’s how I did it. And, in the process, I took a challenge. You see one can keep doing serious art and references which are much more serious, either from the art world or from serious cinema. But you know, here, for the first time, my palette was changed completely. I came up with bright colours and garish imagery in my painting, which happened for the first time. Of course, people loved the painting very much. In fact, it’s in a museum in Japan in their collection— the Fukuoka Art Museum. But I think, I feel that I don’t want to be bound or limit myself to one type of work. I keep on changing always. I feel that every time either with my work on watercolour, or work on laminate, or work on shutters or oils, I attempt things differently and I thought, ‘This popular cinema has a lot where I can experiment and explore things in a different way.’ And a very different kind of a genre would come out of this if I try. A different kind of narrative would come about in my painting, and I should do that, because I also like that. It is not necessary that I would sit through the films every time I was watching them at home but, and I must tell you that I really am quite familiar, particularly with the actresses, villains, comedians, heroines, and these were the kinds of things that were quite common in the seventies or eighties. The hero, the heroine, the villain, the character actors, the father, and the mother, and the extras who support them in a different way, like the servants or people who would come and give a cup of tea and things like that. I mean, I know everyone, including the, you know… I can make out by listening to the flute that this is S.D. Burman and not Salil Chowdhury, or I can say this is Sajjad Hussain and not Ghulam Mohammed. I am that good in understanding, the music particularly. So, Madan Mohan and Jaidev, all these people. Actually, there’s a lot of love for films, I must say.

Well, that in itself is a very good reason to keep it alive. But, I also have to ask you, most of the references are from older films. Is that because of nostalgia or because the newer Indian cinema has just not been able to sustain your interest in that way?

Yeah, I must tell you that. I would not say nostalgia because when I was watching those films, even at that time, there were some films that I liked and some films, which I didn’t like. But frankly, say, after 1980 onwards, or maybe in last 20 years, the Hindi films which emerged, I never liked those films really. Very few people, very few, literally like… I want to watch Talaash, say, Aamir Khan’s films. Even the early Aamir Khan films I have not seen, but I think after Lagaan, five or seven films that came in this decade they were all, I thought there is someone who’s thinking or wants to take films to a different level. So, I think there are very few, whose films I enjoy. Because first of all music has very much been a part of films all these years. And the contemporary film musicians, their music, and the songs— I very rarely like. It’s… yeah, I don’t know, but I tell you one thing that recently, when I saw, which film did I see of his… Anurag Kashyap’s? When I saw his film, Gangs of Wasseypur, the recent one, but the first one… I think, no, I saw it on DVD I think… Black Friday. When I saw that film, initially I said: ‘Okay, the bomb blasts and all those things… ’ But when I saw the way the film moved, the way it travels, and there’s also travelling happening in the film, and I thought this is something interesting. And then I saw Dev. D, and then I saw Gulaal. I said: ‘This is someone who interests me.’ I like the subject matter, the solid performances, the great camera work, and the very unusual take on music— the songs composed are totally different, not the way normal Hindi films would have it, so I think there I felt that there is something. And then of course, I saw both the Gangs of Wasseypurs, and I like his films. He’s good.

I wanted you to tell me a little more about your Charulata images. Again, one of your Ray references, how did that come about?

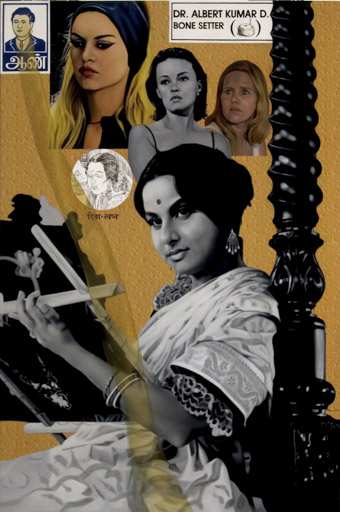

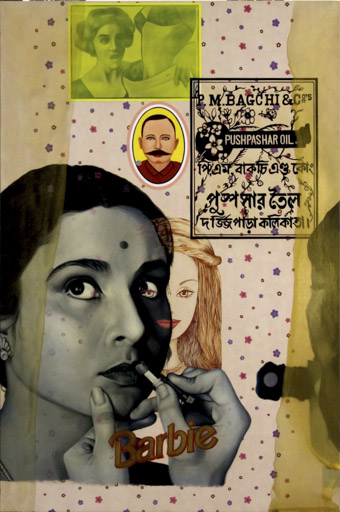

You know, I actually was doing a series called ‘Saptapadi: Scenes from Marriage’ regardless. There were 24 paintings on laminates and I was doing the readymade laminates, like mica, which already had a pattern on it and I had earlier done works on that medium. Initially, of course, Saptapadi was also a film in Bengali, with Uttam Kumar and Suchitra Sen. And Scenes From A Marriage, it’s also a film by (Ingmar) Bergman, a very serious film. And I thought I wanted to sort of work on this subject of marriage: man, woman, the husband-wife relationship. And I thought, what would happen, what kind of imagery would come about? And soon I realized that if I take this in a Bergmanian way then it’s going to be very boring and I wouldn’t be able to engage my viewer. And even I would not be able to handle the subject probably or maybe it would become too personal. And if it would become too personal then maybe I would find it difficult to engage my viewer and soon I realized, ‘Okay, create a fiction, create a narrative,’ which is not necessarily a truth, but go to a wide range of images from calendar art to popular films etc. And in that case, I had, of course, three films, with Madhabi Mukherjee, which Satyajit Ray made – Mahanagar, Kapurush, and Charulata. All these films had the wife very much there, the central figure, and a relationship with the husband, or ex-boyfriend. So I thought it would be great to have three paintings called Arati, Karuna, and Charu, these three characters from Ray films. Also, since I like all these films so much. So I basically wanted to do a portrait of Madhabi Mukherjee also. And when I painted ‘Charu’, I thought why not have three other actresses from European cinema, which was anidea that came in the process. And I painted Brigitte Bardot from Godard’s film, Contempt, Jeanne Moreau from La Notte (The Night) by (Michelangelo) Antonioni, and of course, Liv Ullmann from Scenes From A Marriage. And having them together in one picture plane, these four actresses from the four greatest films, according to me, and scenes from those films together in one picture plane would be fantastic to just look at. Beautiful actresses, great actresses, and great films, and I just enjoyed doing that painting. In fact, I kept it for myself. That work is with me in my collection.

Did you ever get a chance to meet Ray?

No, never. I was too young and of course in ’91 and ’92 when I was away in Paris for my scholarship, I think it was the month of May or April (April 23, 1992), he died. And I remember the front page news of every newspaper, ‘The Master is no more’, on TV channels, his interviews, and other films were on. And I noticed, in fact, you know my biggest regret is his movies most of which I now watch on DVDs are rarely shown. Sometimes in a film club screening, but, you know, never screened here. His last film Agantuk was released in Paris then, but it was never released in Bombay. Of course in Calcutta people can see Ray films sometimes but not in Bombay. So that was a big regret.

Would you have liked to meet him and show him some of your work, which references his movies?

When I had my first solo show in ’89, there was a small, tiny catalogue, which I had sent in, to his Calcutta address, but that’s it. Never met him.

But, in any case, like you said, your quotation comes more from love, more than coming from, you know, picking up bits of craft, directly following a path that someone has followed. It comes more from expressing your love for what you do, which also should bring me to the series you did for the ‘Cinema City’, project in 2012 for NGMA. The first thing that of course struck me was you painted the villains and station signage together, and that this is the Central Line that goes from Ghatkopar to Victoria Terminus and it’s interesting how you… if somebody knows Bombay they would know that the Western line is a more ‘heroic’ line and this is the line that gets beaten. So, again, a sense of humour is very visible but how did you allocate the villains to the stations?

Yeah, well, actually long back when I was in the final year at J.J. School of Arts, was when the painting about the Ghatkopar stations signs called ‘Homage to Ghatkopar’ came about, and you would see the actual scale of the canvas and there are two types of signs— one, where the station ends, a long rectangular sort of a thing, and in between you have this metro sign, which is… So, what I did was I went back to the small scale and so when you see this, one of the questions is whether is it a painting or is it a station sign? Because it covers the whole thing. It doesn’t show the tracks or trees or other people or platform, nothing. Just that. You are so close to the whole painting that it’s exactly the station sign, you know, which you see. So, that is one of the questions: Whether is it a painting or is it a painting sign. That’s one thing which I love, that kind of a pictorial puzzle to put in front of my viewer. Second thing, when we were discussing the ‘Cinema City’, it was obvious that it’s a city because the station signs are there, and that too Bombay, and that too the Central Railway line, because Ghatkopar, where I live, that comes on the Central Line and from Ghatkopar to Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, or CST, there are 13 stations, and I added the 14th one— my name. If you go near Vapi, in Gujarat, there’s a station called, a small town called Atul, where I put Bindu.

But, how did you choose which villains go where? Clearly you have reserved Pran for Ghatkopar, which is artist’s liberty so I guessed you picked the best for Ghatkopar.

Pran is my favourite villain and I have always remained that way. So, I was always clear that I would like to have Pran on Ghatkopar.

And, Gabbar would have to be on CST.

Yeah, exactly, I thought Amjad Khan, you know, but there is no reason. Like a lot of people were asking me whether some of the actors at some point lived in these specific suburbs, and I said, no, except for K.N. Singh, who lived in Matunga. Actually, I had another image there previously and I read somewhere and I said, ‘Oh! If he was living in Matunga, then I have not yet finished the painting so let me have Singh in Matunga.’ So, I just added him, because I like him also, very much.

Amrish Puri, of course, lived in Juhu. But he’s shown at Sion, so, there was no reason why he was at Sion? The rest of the selections you just made randomly?

Yeah, and also because the local name of Sion is also ‘Shiv’. And I think when I chose this image of Amrish Puri from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, from there he looks like some kind of a… he looks like some kind of a priest, who’s probably not a good man. So I thought, ‘Let me have one at Sion, Amrish Puri’, but otherwise, basically it was just going to be 14 villains, so which 14 people should be there. And the people who I enjoyed very much, that was important, you know. And that’s kind of how I selected people like Shatrughan Sinha, Jeevan, Shakti Kapoor…

That’s a very immaculate choice. But the youngest villain that you have is Gulshan Grover. Would you say that the era of villains is over now?

Yeah, the kind of villains… like yesterday I was watching your interview with Amitabh Bachchan, and I said let me see the website and he said, how earlier it was like either the dacoit or Thakur was the villain. Then, the times changed, and the politicians came, and then the underworld don kind of villains came, with Ajit and many others. So with the story and the heroic aspect— of a hero and his glory, the narrative was such that it was the demand. But I think now probably, I can’t comment much because I haven’t seen many contemporary films, but, I think, now it has changed, and probably what was interesting about these villains was that it was very stylized, the way they would talk, the way they would dress, or the way they would… like if you watch K.N. Singh, the way he would put one eyebrow up, the way his eyes would move and all, it was very special, I think.

But I think while basically trying to put the villains from cinema on station signs, the most important aspect is also the surface of the painting, which is kind of a very cracked surface and as if things are falling apart. Then blood drips and there’s those things. And I know what we have gone through, the whole country actually, but Bombay during and after the (Babri) mosque was demolished, the serial bomb blasts, the rise of underworld, terrorism, and 26/11 and all these things, I also think it’s an elegy, I feel. This series is an elegy to the city. Yeah, I mean, not that these people are bad and the city is bad, but the element of evil, which makes one nervous, scared, and there’s fear and I think I wanted to say that as well, with a…it falls in the popular style, with popular culture, with station signs, bright colours and popular actors from popular films, but there is also an underneath feeling of the pathos, sadness, fear, doubts, and loss of faith.

You know, you said that your references from cinema was one way to connect with your first, premier audience, your viewer, which was the people you grew up around. You have come along a long way, like you have said; all your paintings have been shown all over the world. How does referencing work when you have such a diverse viewership of art? Does it become restrictive, because obviously, not everyone is going to get every reference? I mean, there will be a certain viewer of yours, who would not have seen Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage, and maybe a lot of your Japanese viewers would not have watched Sholay? So, experientially what has your experience been? Does it become restrictive or does it become a very interesting exercise in layering or a sort of exercise in interpretation, between the art and the viewer? What is your observation?

You are quite right actually. Because often I have quite specific references in my work, which are not necessarily… Often people would recognize those sort of things. But along with that, there are also some other things, which I also add or include in my painting, like one of my paintings ‘Gangavatra: After Raja Ravi Varma’, on the descent of Ganga. Now, out of the earlier graph of Ravi Varma I painted that and on the river which comes from the sky, there’s a female figure which Ravi Varma painted. On top of it I had superimposed ‘Nude Descending A Staircase’, by an avant-garde early 20th century artist, Marcel Duchamp. Now what happened when I did that painting, my mother, when she saw it, she is familiar with this image, and she’s familiar with the myth of Ganga, and so she recognized everything but she could not understand the very abstract, dark kind of a form which is superimposed over the image of Ganga, and so she was quite baffled. So, what happens is when I am showing this image through slide presentations or through the actual painting, when it travels abroad, people are there in Europe and they recognize and are familiar with Duchamp, Marcel Duchamp, this well-known iconic image of earlier 20th century art, but they are not familiar at all with the myth of Ganga. And now I am aware of both. So then, they are also puzzled there, like my mother. So, I think, in the process, I engage them for a longer time. They try to understand what it means, because partly they have got it— it’s only a part that they are not getting. So, I think, I like to puzzle, put my viewer in a position so that they have to struggle hard to understand, and in the process I have realized they remain with the painting for a longer time. And actually, physically also sometimes, but mentally also, psychologically as well.

There’s this chance of not reaching to a large audience. But I think of how large an audience you can reach and how much one should attempt. So, ultimately, I just do it. The first thing is, whether I am enjoying this or not while doing it.

I am going to come back to Ray for a second: do you feel like his education in Art—you know he went to Shantiniketan, was (Rabindranath) Tagore’s student—that showed through his films? Could you see it as tangible?

I think he also has said that. After doing Economics or something, it was his mother who insisted, he wasn’t keen to go to Shantiniketan, but she made a big fuss and he was forced to go to Shantiniketan to become a painter. Of course, he never continued painting, but he became a graphic artist and went into advertising. But two years of what he studied under Nandalal Bose and, of course, as a young boy, he did meet Rabindranath Tagore, and I think that had… Binod Behari Mukherjee was there, and of course there’s a beautiful documentary called The Inner Eye on Binod babu (made by Ray), but I think certainly— Shantiniketan. Because he got acquainted with the western classical music there, with a German teacher who was there, who would be listening and he would kind of put notes and that’s how he learnt notations there. And I think the basic philosophy of life, like in one of the interviews he says that Nandalal Bose said that when you draw a tree don’t draw the branches and leaves first and come down, tree grows like this—not from the sky—so put your strokes also in that manner. I think this is quite a key point in Ray’s approach to all his movies, and general philosophy of his life, that howI mean… it’s difficult for me to say, but he has an extremely sensitive approach to relationships, towards human beings, the life in the village or in the city. How much to show, how much not to show, that control, that immense control over the expression, that’s something that’s definitely Shantiniketan, and apart from that the great visual sense this man had in terms of tonality, in terms of form, in terms of texture, you see. I mean Pather Panchali is sheer unbelievable, the old lady and the shadows and the young boy, all that I think. The amazing thing also is the drawing and painting which he studied there. While we know of Ray mainly as an illustrator, but those drawing qualities… I tell you, it is the best drawing any Indian artist would probably draw. I mean, of course, there are painters and there are masters who had great drawings in their oeuvre but the sketches and drawings of Ray are not in the way of normal illustrators, which you find in applied art, in Bombay or in any other art school. It’s not that, that illustrative quality is not there. It’s pure painterly qualities, which are there, which I admire. They are great, they are fantastic. Even the doodles and the tiniest thing about the costumes, which he created for his scripts, which we see, they are masterful absolutely. It’s unbelievable. I mean, so many aspects together in one man, it’s just sheer genius.

Other than Ray, who might be a couple of filmmakers who have influenced you indirectly? When I say indirectly, I mean with their craft. What they do with their medium, inspiring your work with your own medium?

I remember when I was studying in Sir J.J. School of Art, we were members of a film society and we would go to see all kind of films. And the first time I saw a film by Jean-Luc Godard, the French filmmaker, and there I noticed that often there’s a soldier there in Remora print on the walls, or even Pierrot le Fou, or the Picasso reproductions on the wall. All that I saw because I could relate, ‘Oh Picasso prints or remora image in the background and something else is happening in the front.’ And the complexity of making the film itself, the way the shots were taken, the way the narrative was told. Often I would not follow it. And much later, Godard’s films, which are much more complex, which are difficult to understand sometimes, I think, but I think too layered, having various layers, working simultaneously, and seeing what happens, that kind of thing in my work has certainly come from Godard. Meaning: the language of the painting. That itself is a subject matter for me, or a painting in itself, or what if that is my subject matter. If Bollywood is not my subject matter; if the city of Bombay is not my subject matter, but the act of painting, what if that becomes my subject matter? What will happen? What kind of painting? And of course, I could hear American artist, Jasper Johns,who also has this thing… he was heavily influenced from philosophy of (Ludwig ) Wittgenstein, German philosopher, and he would select, he would want to say Red, but you say Red and you mean Blue, then what happens? I mean, I want to say something. Like that’s what happens with the languages, like I want to say something and I am using this language and I have a limitation with the language, now I am trying to explain and convey these things, but am I saying what I am really feeling? What I am saying is one thing, and what I am feeling is another thing, so there’s a gap in between. So that gap he would sometime attempt to focus on, and somewhere I feel in Godard that the language of cinema—shooting, actor, the city, content—he suddenly becomes detached. And he would show you a slightly dislocated kind of thing. And in Gujarati, we have this, though quite old and not that well known, poet called Labhshankar Thakar. Now Labhshankar had a series of poems about the creative process itself, the poem is about writing poetry, and then what happens… So, I think, I was quite influenced, in that sense, more than Ray. Of course, as I said, there’s no direct influence of Satyajit Ray on my work but it think it is Godard.

If I quickly asked you to name a couple of films for each category. A film, which you remember for the portrayal of a character? A film or a couple of films that you remember for the way in which they portrayed a particular character? What comes to mind first?

I mean, there are so many films actually. Few days back I saw a film called Million Dollar Baby, a film by Clint Eastwood. And it was a fantastic film, and the actress, the way she performed, Hilary Swank, I think it was great. I also enjoyed the Dirty Harry series, so that’s also another thing. But it think, I mean, all Satyajit Ray’s films have lots of great characters like Chhabi Biswas in Jalsaghar, then Sharmila Tagore in Aranyer Din Ratri, and the young Jean-Pierre Léaud in Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows. And many, many films are there.

Okay, what about building a mood? A film you remember in the way it built a mood? Or, a couple of films?

Oh! Bergman comes to my mind. A film called The Silence, it has a real mood in it, you know, with characters and actors— amazing. And all Bergman films had a really profound, I wouldn’t say grief, but a poignant melancholy and they were extremely sensitive. So, Bergman I like. I also enjoy (Andrei) Tarkovsky. Tarkovsky’s films have that kind of a thing. Mood, the way water drips or milk flows. Stalker, The Mirror, and, of course, Andrei Rublev. Also Ivan’s Childhood. So these films I remember. Then much later, I saw, if you say, The Three Colors (a trilogy) by (Krzysztof) Kieślowski, those films I liked.

What about a film you remember for stylization?

I had not seen it for a long time, but when I saw, not recently but some years back, (Quentin) Tarantino’s film Pulp Fiction. It’s obviously a very stylized film, so that comes to my mind; it’s an obvious choice. I think Anurag Kashyap has certain style, and manner, although there’s natural acting, but I think he has a certain style, that’s a good thing. And, I also like very much Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome, you know, and it is a fantastic film with K. K. Mahajan’s great photography and it was quite a stylized film. In the way it’s shot, in the way it’s cut, in the way the narration has been told, it is good.

You know, you have touched upon this a little earlier when you were talking about how you were very interested in your viewer, unlike, a lot of artists perhaps. But, has cinema in any way influenced who you engage with? And, how you engage with people? Can you think of any instances?

In my own context?

Yes.

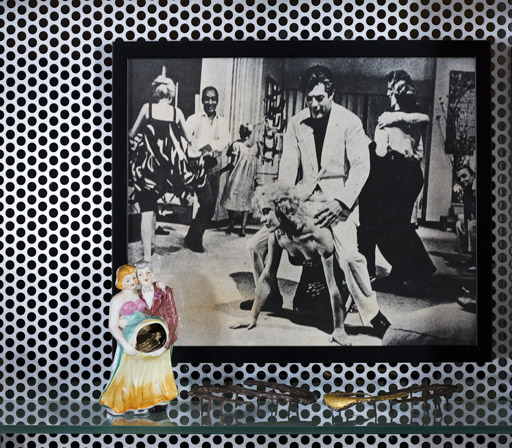

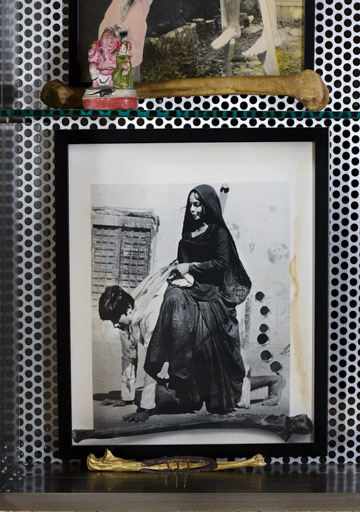

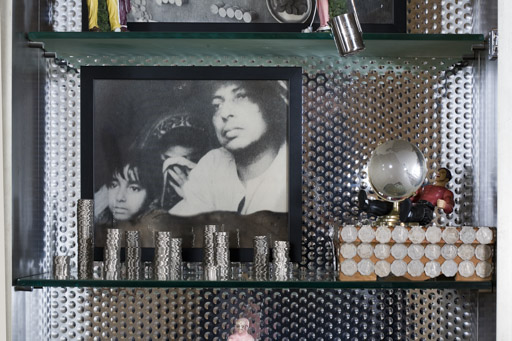

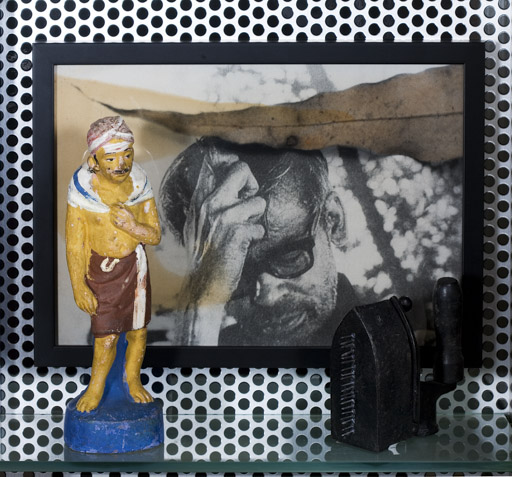

No, I think, what I feel is that it’s strange that when I see world art. Particularly, the art of paintings, and there are a lots of minimalists. There was this period in sixties, seventies in America, where paintings were just flat colours or very little sort of gesture and action, so I like those work as well. But what I noticed in the west, particularly in visual arts, they are more… they hold, and they don’t go for ‘loud’ or to say much. It’s very minimal. Minimal is the word, which I find, even if they do video work, even if they do sometimes sculptures or installations, it’s the minimal which is like our very own Anish Kapoor, Indian born, living in London, doing work from there, large scale things, huge sculptures, amazing artist, no doubt, but I would still feel that there’s a certain aspect of minimal, which they follow, that’s Western. But in India, I feel I can’t do that. I feel I will have to tell you everything, you know? When I was in the old chawl—and I still go, my studio is still there—everyone would ask, who had come? Why he was here? This would come on television or is this a special film? Tell us, and everyone wants to know everything. And we are kind of intimidated, and people would come and talk to you all the time. So, I think, in a country like India, a city like Bombay, how can you be minimal? So, I think in cinema I find, a lot of things have been told. And particularly in Hindi films you have emotions shown through songs, through weeping and crying, through festivals and all kinds of things. You know, things are suddenly… either they are in Matheran or in Switzerland; you don’t get to know those jumps which are there, which I think is fantastic, which I like. And, I think that comes, so when I started doing these cabinets I thought I’d keep it a little small, but then gradually, I had to have a lot of things. I must have a lot of things in my work, so I think probably that has to do with my interest in cinema because there’s a story, there’s a music, there’s actors, emotions, all these things, and I put them together. But some of my friends often tell me that why don’t you make a film? Now, probably okay, in those days, you opted for pure painting, no doubt, but often, just yesterday I got this mail from a friend called Lynda Benglis, one of the top artists from America. I had sent her some pictures of my installations, and she said, ‘Oh! I see lots of stories there. It’s a film, it’s just like a film.’

You know, the line in Hindi cinema between the commercial cinema and the Art cinema is very, very distinct. We have two separate worlds. I want your opinion on how that’s reflecting currently on the art world in India? Given how important commerce has become now, is the line between the work that is dictated by commercial concern and the work that purely comes out of the creative vision of an artist becoming more and more distinct? In other words are market forces beginning to dictate creative content very forcefully in the art world?Like it is in cinema? Or, do you think it is still not too distinct a line between art, which has overt commercial concerns?

No, I think… see as far as fine art, visual art is concerned, there are people who start with serious art, and once they get settled, known, their work starts selling. I think then they keep on churning the same stuff, and that’s the biggest problem. You know, then that becomes more commercial, so that is one, it’s a serious thing. So, one has to be constantly alert, why one is doing it, for whom one is doing it, and if a painting becomes a stepping stone for me to achieve name, fame, success or money then I think there’s a big mistake. So I am extremely alert about this, so this should not happen. That’s one thing, and lot of people are aware of this, of course, but then there are temptations and that happens. But I think as far as cinema is concerned I feel that basically it’s an expensive medium. And if you do something very serious then probably it would be difficult to reach people, and that’s the way probably it is, and that’s why no one wants to invest in that because a lot of money has to go for making a film and then there are two separate parts. That’s why we have very few people, there are many, many young filmmakers, there are many friends of mine, who would like to do films in a serious way but for a long time, I have not heard of them, I have not seen their films while the usual churning of commercial type of cinema is there. But people say that there’s no art film and commercial film. It’s only a good film or a bad film. I don’t believe in that. I would say, there’s an art film and then there’s commercial film or popular film. Within art film, there are good films and bad films; within commercial films there are good films and bad films. So that happens you know, and I think in that case, some people’s films run, some we like, some we don’t like, that happens but I think it’s just… I personally feel that often people from the Hindi film world say that their audience is lower middle class, poor people, but India is a big country and to forget three hours of pain and worry, we make these films with songs and… I think this is underestimating people and their… I mean all kinds of people see films. I am an educated, sensitive artist. I also watch films. So am I not supposed to see the films? Only someone who’s doing a small business on the street? Is the film only made for them?

Also, even that is underestimating. I mean, we grew up with the folk culture, and if you look back to 100 years ago, the man on the street, the so called ‘proverbial poor man’, was listening to a rich folk tradition and their music and the stories and, you know, so it was not exactly…

So, I feel that just to give this excuse that: ‘We make films for common people. And common people are like this’, that is something… well, probably true everywhere in the world. And people like those kinds of films probably, but I don’t know somehow, it’s a very… at one side there are so many popular films, which I really like and enjoy and at the same time I hate this Hindi cinema. I hate it. It’s actually that kind of feeling.

Eye of the Beholder: Atul Dodiya

InterviewNovember 2013

By Pragya Tiwari

By Pragya Tiwari

Pragya Tiwari is Editor-in-Chief at The Big Indian Picture.