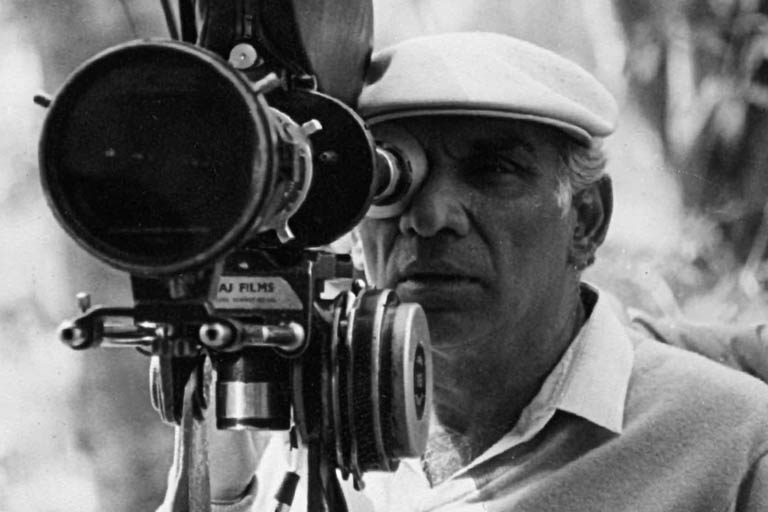

An interview of Yash Chopra by Rafique Baghdadi, done after he had made Mashaal in 1984.

Yash Chopra has been making films from the last thirty-five years. Most of his films have been successful— from Dhool Ka Phool, Waqt, Ittefaq, Deewar, Trishul, Kala Patthar, Noorie, to his Mashaal, which has been favourably received by both the public and the press.

Your film Dharamputra (1961) was close to the partition experience. How were you personally affected by the events during that period?

I studied in Lahore, but I had to come to Jalandhar after my primary school. Things happened on both sides. Hindus were killed there, Muslims were killed here. I saw massacres with my own eyes and lived through the frenzy, the foolishness and the madness of the time. It was not necessary to be in Lahore to experience the trauma. What I saw in those days I used in Dharmaputra, but I didn’t make Dharmaputra because of what I saw. When I read the novel, something of that experience must have spurred me to make the film. The scenes in the film looked realistic because I had witnessed those scenes myself. Today, if an Indian director has to portray war, it would be based on what he has read about it, or heard about it or as he has seen it in the foreign films. In India, in the recent past, we have not experienced war.

The thematic content of your films have usually been something new and original. Even your earliest films, like Dhool Ka Phool (1959), Dharmaputra (1961) and Waqt (1965), broke new grounds in terms of their themes which had not been tackled by filmmakers in India till then.

At that time we had a story department. They would come up with stories and if we liked the stories we would turn them into films. Now that set-up has gone. Different writers come to us with stories from which we select what we like. I feel that even after I branched out on my own, after Admi Aur Insaan and Ittefaq, I showed in Daag how a man under certain circumstances is landed with two wives. The treatment was emotional and romantic but what I wanted to say was that fate plays a decisive part in our lives and that we have to make compromises with it. In the film, the three people, who had each other, had to make a compromise and decide to live together. Life is a compromise. In Kabhi Kabhie, I wanted to say that the social binding of the tradition should be broken. When a couple gets married no one has the right to go back to the girl’s past, and drag it into her present. No one does that to a man. If a man has an affair before marriage it is not held against him. Why should we hold it against a woman? Deewar was a very well written script; and in Trishul, I showed the conflict between father and son and the son’s obsession with destroying his father. The film has a new angle of revenge. I think that was the first film with that theme. Others followed. Sometimes people do not see the newness in a commercial film with a big cast. Similarly, Silsila presented a different subject— extra-marital relations, which has been followed by Arth, Yeh Nazdeekiyan and others. So, from ’59 to ’84, in the twenty-five years that have passed, I have come out with new subjects as society changed.

Would you have achieved your success without your brother’s support?

I don’t think so. Whatever I am, I owe to my brother…

Your films are usually clean. You avoid rape and cabarets. How did you bring in these elements in Joshila?

I think that was the only film in which I showed those scenes and I’m not happy about it. The film was made at a time when I was at a crucial stage in my life. I was making the film for Gulshan Rai and something of Johnny Mera Naam must have influenced me. Also in those days I had separated from my brother and was emotionally upset and unbalanced. A stage like that comes in everyone’s life, I suppose. I had this feeling of insecurity. But in all my romantic films I don’t find the need for a villain or a vamp. Life itself plays a role, in a strange way. The theory that directors have is that for any victory there has to be a powerful negative force. I like to make a film which the whole family can enjoy watching together. Even the romantic films should be done with aesthetic taste.

Ittefaq was a well-controlled film. Why do you not make more films in this genre?

I feel a suspense or a comedy film is not a very lasting thing for a filmmaker. The moment the suspense is over, the next audience knows what it is all about. Very few suspense films are made in the world today. Films where basic emotions are involved last longer. Suspense films involve a lot of technical gimmicks. The heart is less there. The basic plot should be emotional, action should come later. We should not have action for action’s sake.

Love is predominant in your films as well as ‘Punjabiness’! Could you comment?

I love to make romantic films. I don’t like crime films. My projects are all based on emotion. In Mashaal I showed slum boys, and the underworld mafia, so action was in-built in to the film. If I take a film like Kabhi Kabhie, the atmosphere changes. You can blame me for the ‘Punjabiness’. I know more about Punjabi music and culture than I know of other languages and this I present because I know it best. I may not be able to handle what I don’t know.

How did you come to make Mashaal, which is neither a commercial film nor an art film?

I liked the basic theme which was expressed in a dialogue. It referred to the reversal of roles. The good had turned bad, and the bad had turned good and their goals changed consequently. The situation is compared to a football game where, after half-time, the goals change. Secondly, I was influenced by the likely emotional impact of Waheeda’s death in the film. I think the central idea is important, both for a commercial filmmaker, and an art-maker, to train the film’s appeal. I had made a soft film, Silsila. I wanted to make a hard, realistic film.

But it was risky?

I felt the film would run. Of course the inherent risk was there. Kabhi Kabhie was a risk. I had a new idea. But a soft film with a small idea, with a small budget, may not look risky. Silsila was risky. It was the first film on extra-marital relations. But it did not seem risky because film was filled with big stars. My mistake was in the casting which made the audience look for something which was not there in the film. If the girls were different in that film, people would have taken the film as any other film.

How do you view reality in Mashaal? Events are apparently shown to extract the maximum dramatic impact.

I don’t make very realistic films, or art films or experimental films. By reality, I mean that everything in the film should look normal. You should feel you know the characters, that you’ve seen or met the people. In Mashaal you should take the sequence into account which shows that his (Dilip Kumar’s) press has been burnt and his house taken away. These are cinematic liberties taken as we want to make him look isolated and alone. The rain delays them. Now I have witnessed the following scene many times. On a rainy night, if you try to get a lift, you are not likely to be successful. The reality is there, but we have taken cinematic liberties. Given the circumstances, I feel the subsequent events can happen. It rains, they go for help and are alone on the road. Please don’t stop to give them a lift. His wife dies. I don’t think the events sound unreal.

How closely do you work with your scriptwriter?

I cant work unless there is a close and complete rapport with anyone. Kabhi Kabhie and Silsila were my ideas which we developed. Deewar was a complete script given by Salim Javed (Saleem Khan and Javed Akhtar). Trishul and Kala Patthar we worked on together. Mashaal was suggested to me by Javed and we discussed and developed it.

Except for Dharmaputra, you have not based any film on a novel.

I feel we don’t have good writers or stories in Urdu or Hindi literature. Copying English novels would be foolish. There is really a dearth of good writers.

What about Vijay Tendulkar, Mohan Rakesh… and others?

When the script takes the shape of a film then one realizes the extent of the risk. Why take the risk when one is spending big money? These scripts are suitable for small-budget films. The scripts have new ideas, but because the film is made in a small budget, the risk is reduced.

What do you think about small-budget films?

There is only good cinema and bad cinema. Everything finally boils down to commerce. A small-budget filmmaker will feel that he can take only so much risk and so he reduces his budget, takes his cast accordingly, calculates his likely earnings and is satisfied. A big-budget filmmaker thinks if he takes small people he will not get the kind of success he is spending for. All filmmakers finally come down to commerce. Even the art filmmakers.

What about the new language of their cinema?

I beg to differ. I have seen the work of Govind Nihalani, Satyajit Ray and Shyam Benegal and they are good but there are some filmmakers whose so-called new language of cinema is an insult to cinema language. Cinema is an art and it is a combination of all the arts. I must have some aesthetic taste for photography, dialogues, clothes, poetry, music, scripts, song, acting, screenplay, locations. I have no right to abuse this art. They just want to be different. People bold enough can change the language of cinema.

Have you seen their films?

I have seen them all. Ardh Satya, Junoon, Ankur, Manthan say something brilliant. They are not abusing language. The subject has to be good. Not the technical shots— that is gimmickry. See the last shots of Ankur. I take my hat off to Benegal. 36 Chowringhee Lane was good. Even Baazar said something.

You have been in the film industry for twenty-five years. What kind of memories do you have?

Twenty-five years is a long time. I have tasted the mixture of good, bad, indifferent, bitter and sweet memories. I have only one love and that is film. I don’t have many diversions except for poetry, music and reading. As long as I am making a film I am on top of the world. I have worked with everybody and it’s a matter of good luck that most of them have been nice and kind to me. I’m not involved in any politics or controversies; in calculations and manipulations. The moment I get my script and my casting, the other world fades out. I have pleasant memories and only a few which are bitter, but they are of a personal nature.

Talking Films with Yash Chopra

InterviewOctober 2014

By Rafique Baghdadi

By Rafique Baghdadi

Rafique Baghdadi is an author and a journalist and a walking encyclopedia on films, journalism and Mumbai.