-

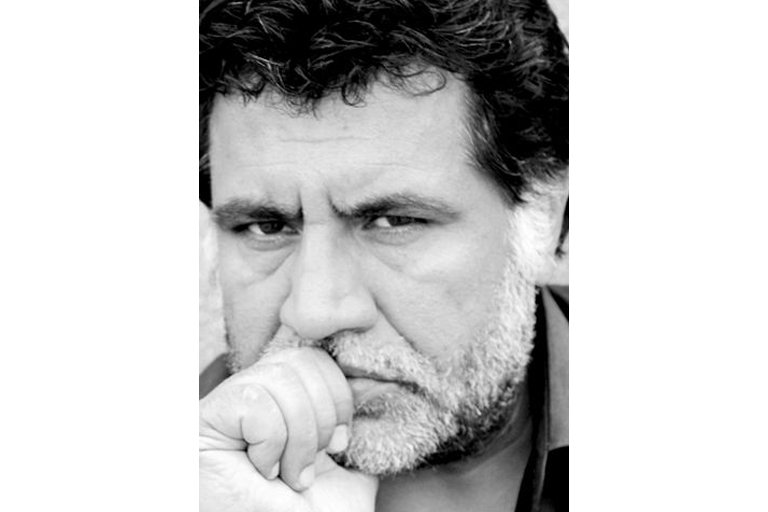

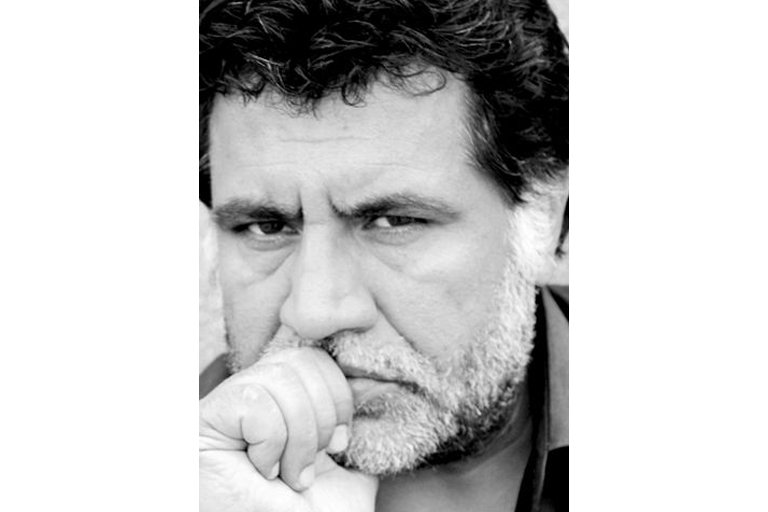

Siddiq Barmak

Siddiq Barmak -

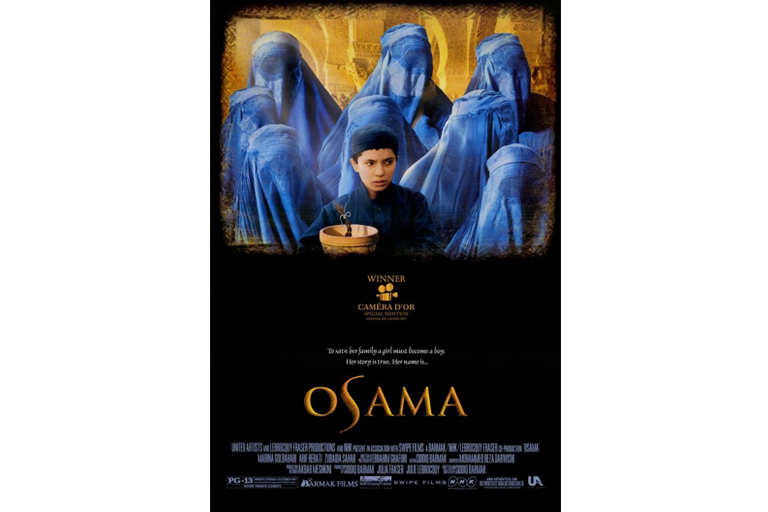

Poster of Osama

Poster of Osama -

A screenshot from Osama

A screenshot from Osama -

A screenshot from Osama

A screenshot from Osama -

A screenshot from Osama

A screenshot from Osama

Voices from Afar is a series of interviews with filmmakers and film professionals, critics and experts from various countries around the world. The idea is to, through these voices, better our understanding of films and filmmaking communities which may seem alien at first glance, but whose joys and struggles, on closer examination, may have a deep resonance with our own.

Siddiq Barmak, 51, is an Afghan filmmaker, screenwriter and producer. He left Afghanistan during the Taliban regime to live in exile, in Pakistan, from 1996 to 2002. He returned to make his first feature film, Osama, which follows the life of a pre-adolescent girl living in Afghanistan, who disguises herself as a boy in order to be able to support her family. It was the first film to be shot completely in Afghanistan since the Taliban banned filmmaking in the country. Barmak received a special mention for Osama in the Camera d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 2003 and won the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film in 2004. His second film, Opium War, a black comedy, won the Golden Marc’Aurelio Critics’ Award for Best Film at the Rome Film Festival in 2008. Barmak is also the director of the Afghan Children Education Movement (ACEM), founded by Mohsen Makhmalbaf. He is a mentor to many emerging Afghan filmmakers.

When we finally meet Barmak, in between Mumbai Film Festival screenings, it is at Kyani & Co., an Iranian joint in South Bombay. He sips on some Irani chai, listening to our questions intently. He then proceeds to speak about films he remembers from his childhood, political turmoil in Afghanistan, the hopes he has for Afghan cinema, and more.

What kind of films did you watch while growing up? What were the films that inspired you to become a filmmaker?

Actually, we grew up on Indian films. We watched everything. We watched a lot of commercial films from the 1960s, but I must say that I really admire Shyam Benegal saab a lot— his earlier films Ankur and Nishant. These kinds of films had a big influence on me at the time, when I was young. Of course, when I went to Moscow for a higher education in cinema, I realized that there was a new wave of cinema from Italy, France, and Russia. But in my childhood, and when I was a teenager, Shyam Benegal saab was my favourite.

Did Iranian cinema have an influence on you? Your film Osama was partially funded by Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf…

Yes.

And many parallels have been drawn between your style of filmmaking and the style of the Iranian new wave…

Iran has a lot of great masters like (Abbas) Kiarostami, Makhmalbaf, Jafar Panahi, and even (Asghar) Farhadi’s last two films… I love them. But I must say I get influenced by different filmmakers from around the world. As for why we are so close to Iranian cinema— we have the same culture, the same tradition, the same literature, the same language. That’s why you feel it looks like an Iranian film. When you are speaking in one language, when you’re reading poetry in one language, such as Hafez-e-Shirazi, for instance, or Saadi, or Shahnameh (an epic Persian poem) by Ferdowsi— you can find this Shahnameh being celebrated in a very remote village in Panjshir, in North East Afghanistan, as well as in Shiraz, which is in south Iran.

Panjshir is where you were born?

I was born in Panjshir.

We’ve read that Osama is partially inspired by a true story. Can you elaborate on that?

It was a true story. Actually, I was searching… I wanted to make a short film together with my friends in exile. I was living in the Northern part of Pakistan, during the Taliban regime. So I was searching for a kind of subject or story. And I saw this short story that was published in an Afghan newspaper in Peshawar. There are many Afghan refugees in Peshawar, and they have their own publications that they read. This newspaper was called Sahar, and there was a true story about a little girl who wanted to go to school, but it was forbidden for her by the Taliban. Then she decided to get dressed like a boy and go to school. But unfortunately she was found out, everybody knew about her, and the police forces—the religious police forces of the Taliban—came in and punished her. I was really shocked by this, and I started thinking about it, and started writing a script. Then I saw that this story is not a short film. It needs to be a big feature film. But it was impossible to make the film at the time. When the Taliban collapsed, in 2001, I found an opportunity to make this film. But I changed a lot of things, of course, in the story.

That’s what we wanted to ask you about. The initial title of Osama was Rainbow. Also, originally, the film was not supposed to end on a sad note, but you went ahead and cut a lot of scenes which you felt would have seemed too hopeful. Why did you do that?

Because that would be a big lie. Because nothing has changed, because we still have a lot of problems. Also, now there’s a concern about the return of the Taliban, for instance. So my concern was to make people aware about the future as well.

Even after the collapse of the Taliban, what were the biggest challenges that Afghan cinema faced?

Not just the Taliban, it is generally seen that Afghanistan is a traditional country, a very religious country. And there’s a very dangerous interpretation of religion, such as one that translates into keeping women inside a kind of ‘jail’, in their houses, where it is impossible to get out. I think it’s a very bad phenomenon in our society. And not only females— both males and females are still in mythological jails.

What are the biggest challenges Afghan filmmakers face today?

You know, it’s a very long list of big challenges, but I’ll try to tell it in short. In the whole history of the world, and especially in our country, there are big tensions that exist between power, religion, culture, art and cinema. If they don’t get together or find some kind of reconciliation, we’ll never have a good future for art and culture in our country. When power meets religion and both ignore culture, it’s a big challenge to writers, poets, filmmakers, painters… Now for instance, there is a big unity between very radical religious figures and very corrupt politicians. And they are afraid of cinema, they are afraid of culture, they are afraid of poetry. At the same time, they can’t stop artistes. So they simply don’t provide support and create a lot of barriers against art, culture, poetry, and writing. Our only privilege after 2001 is that we have freedom of speech in our society. We can say everything. But we don’t have the money to make films and to tell the stories we want to.

In the last seven to eight years there’s been a surge of new filmmakers in Afghanistan. How do you think their cinema and the subjects they are tapping into are different from those highlighted by earlier Afghan filmmakers?

They are from the young generation, so they view things with a fresh set of eyes. They have more strength, more energy, and they have the courage to tell different stories. They are telling stories that were forbidden for years. For example, these short (Afghan) films that were shown here (at the Mumbai Film Festival)… there’s a big ‘package’ of these kind of films, and I must say that these films are very brave. One of the documentaries is about a girl who becomes a prostitute in our society, and she says she’s telling her story in front of the camera because “you must find me in your sister, in your mother, in your house”. Nobody had the courage to show such stories in previous times but now the new generation is doing it. We have to tell these stories to our society.

You set up the Afghan Children’s Education Movement. Are you playing an active role in training the young generation of Afghan filmmakers and actors as well?

Yes I am. I am teaching at Kabul University, and I’m also helping organize some private, not long-term but short-term workshops to teach them. If there’s any possibility to help in a financial way as well, I do so.

How does the political upheaval in Afghanistan have a consequence on kind of the cinema Afghanistan is producing?

The consequence has been very bad. As I told you, our government is handled by crap people— including the Opposition. They are afraid of cinema, of the power of cinema. They are really scared because cinema is a medium that can tell the truth, and the people will then know what’s going on in this country.

You have written a screenplay, directed three films and also produced and co-produced three films. What do you find more creatively satisfying— writing scripts, directing films or producing movies?

I really enjoy all of these, but most of all being a director. Besides that, I’m enjoying making films in any capacity, whether in the position of a director, writer, or producer. I really enjoy watching films— especially when I watch my own films as part of the audience. I just enjoy films.

Irani Chai, Cinema Afghani

InterviewNovember 2013

By Roshni Nair

By Roshni Nair

Roshni Nair is Trainee Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture

By Tanul Thakur

By Tanul Thakur

Tanul Thakur is Junior Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture