“Life’s like a play; it’s not the length but the excellence of acting that matters.”

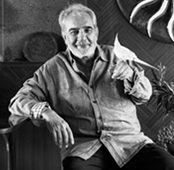

Sulabha Deshpande, 76, has been a founder member of the Marathi theatre groups ‘Rangayan’ (with theatre director Vijaya Mehta and her husband Arvind Deshpande) and ‘Awishkar’. Sulabha and Arvind Deshpande and playwright Vijay Tendulkar were also at the centre of the ‘Chhabildas Movement’ in Marathi experimental theatre during the 1960s and 70s. Her most memorable theatre performance has been that of Benare, the protagonist of Tendulkar’s landmark Marathi play Shantata! Court Chalu Ahe. She essayed the same role in its film adaptation. Deshpande went on to act in several other mainstream and parallel Marathi and Hindi movies, during the seventies and eighties, such as Shyam Benegal‘s Bhumika: The Role (1977) and Kondura (1978), Saeed Akhtar Mirza‘s Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyoon Aata Hai (1980) and Govind Nihalani’s Vijeta (1982), and Tezaab (1988), Ghar Ho To Aisa (1990) and Raja Ki Aayegi Baaraat (1997). Her last appearance in a Hindi film has been in English Vinglish (2012). Deshpande is soft spoken and she says her memory isn’t as sharp as it once was. Yet, as we go over the past at her Mahim flat, with the rain falling hard outside, she recounts the most amazing stories.

How did you begin acting?

My father (Vasant Rao Kamerkar) was a recordist with HMV. So, in a big hall at our home, we used to have rehearsals for songs and plays, which he would record. From when I was four years old, which is when I had begun to speak, I would enter that space and perform after the rehearsals. But my first ‘proper’ role was in school, in the seventh standard. There was a play written by a teacher in which I was cast as a small child. After this I did a play in my first year of college, for a festival.

Did you do only Marathi theatre, when you started out, or Hindi theatre as well?

Both. At first I worked in Marathi theatre. My first work in Hindi was Andha Yug, with (theatre director) Satyadev Dubey in 1964. That was for the theatre group Nandikar’s theatre festival in Calcutta. Four days before the play the actress who was playing Gandhari (a character from the Mahabharata, also in this play) left it, so P. L. Deshpande suggested my name to Dubey. That was the first time I met Dubey. He came to my house and said, ‘You have to do it in four days. You have to leave today.’ I said no at first, because my four year old son was ill. At that time Arvindji (Arvind Deshpande), my husband, used to work in experimental theatre too, which there’s no money in. This was reformist theatre, in a way. He said, ‘Go, because Nandikar’s is a very big festival in Calcutta and this team is representing Bombay and that too in Hindi.’ He would take leave from office to take care of our son. So, in four days, I prepared myself for the role of Gandhari. There was tremendous applause at the festival. After this I did two or three more Hindi plays with Dubey.

What was your first professional play— in Marathi or Hindi?

That was in Marathi: Shantata! Court Chalu Aahe. I had done work on two state level plays before this, but they were for amateur competitions. Even they happened quite late, because I was a teacher for 15 years in the Chhabildas Girls’ School, where I had studied as well. Incidentally, this was one of the reasons why our group was later able to get Chhabildas Hall, for 18 years, to rehearse our plays. That’s how our theatre movement came to be called the Chhabildas Theatre Movement.

Coming back, 1967 was when work began on Shantata… (Vijay) Tendulkarji’s play. It was supposed to contest in a government competition (the State Drama Competition, Maharashtra). It was an unusual play for its times, but it won an award for best play and I won one for my role as Benare, the central character. In about four months, appreciation flowed in from all over the country.

Shantata… has a story behind it. After Vijayaji (Vijaya Mehta) left the theatre group Rangayan because of her marriage, Arvindji eventually came to be in charge of it. He did two or three plays and this was the last one. He said to me, ‘There’s no money, in this field, but there is this government competition. We have good actors. Our writer is also good. So if we win a place in the competition, we will get award money and with that we can do more work.’ There were 77 people (in the group) in all, and their finances weren’t in a good state. Vijay (Tendulkar) wasn’t in a good state of mind then either. His elder brother was ill. But everyone insisted that he write and send in something, so he wrote the first act. There wasn’t much to it— no drama.

So in the 21-22 days the show was supposed to take place in, Tendulkar would write all night and Arun Kakde, who stayed next door to Tendulkar, in Vile Parle, would come in the morning, before the milkman arrived, to deliver bits of the script to Arvindji. Arvindji would work on these bits in the evening after his office hours, make notes, prepare them for the next day’s rehearsal. At night he would explain the characters to me. By the end of it I remembered everyone’s lines and knew all the characters. I wasn’t scared of doing the main role.

But what I found really challenging was that Benare, my character, doesn’t say anything throughout the play. She is not heard. She just sits there. In fact, in the final courtroom scene, the judge says: ‘You have 20 seconds. Say whatever you want to say.’ And even then, for twenty seconds, Benare says nothing. Yet Arvindji said that just one look would explain everything about Benare’s history and her life. It’s okay if she doesn’t speak, he said, she can speak with her mind.

Tendulkar, however, didn’t like that she didn’t say anything even at the end. So there was a big fight between them (Tendulkar and Arvind), because 21 days were nearly up and everything had to be ready. And, with two days left for the play to open, he had nearly finished the third act but still hadn’t given in the end. The way things stood then, the play would have had to end after Benare’s 20 seconds of silence. So, when Tendulkarji came to see the rehearsal, everyone shut him in the hall in which we were rehearsing in. Arvindji said, ‘Write the end and only then come out. Till then we’ll do the rehearsal outside.’ After half an hour, or 45 minutes, Tendulkar came out and gave it to him, and left without saying a word. We thought he was angry, but that wasn’t the case. The truth was his elder brother had passed away, and he was grieving. Even then he wrote it. In fact, I also knew the play really well by the date of performance because Tendulkar had explained everything to us as well, right down to the movements…

Shantata! Court Chalu Aahe went on to be translated into 13 languages. We made it in Hindi. And then someone took on the play for 100 shows. Then we did 150 shows. And then Rangayan shut down and a new theatre group called Awishkar was begun by us. I had suggested the name, in fact.

What was the first film you did?

Shantata… in Marathi. That was the first Marathi film. The second film was in Hindi. And that was Shantata… as well. They had taken a loan from NFDC. Dubey was to direct it. In the beginning I refused to do the main role because I felt the heroine had to look good. ‘Who told you that?’ Dubey said. I said, ‘I’ve seen it in so many films. Heroines are chosen this way. And you have taken a loan for this play. Me playing the lead would be okay for an experimental play but not for a film because you’ll have to pay this loan back. I’ll give you some names, they do good work, and they look good too.’ But both the names I gave him said they wouldn’t do it and Dubey was in a fix. So I agreed.

Govind Nihalani was cinematographer on Shantata… and you’ve worked on other films of his later on. With him as well as with Shyam Benegal. How did those roles come about?

Govind Nihalaniji was a part of Arvindji‘s and my circle. We were close friends. We were all at a party, once, at Juhu Hotel. Govindji, me and Amrish Puri were talking so that both of them were looking at me and I was facing the buffet table. Now, when the waiter came he put paraffin into the fire under one of the dishes on the buffet, to heat it, and it exploded into flames. My face and Govind’s back were burnt.

Govind had just arrived in Bombay then and didn’t have anyone in the city. So he stayed at our home for one and a half months, recovering. Shyam Benegal’s Kondura had started filming, at a village near Madras and Govind was a cameraman on it. He left for the site once his back was okay. I was avoiding work still. Though my face was mostly fine, my eyebrows had been burnt and I was uneasy about getting back on stage or screen.

Shyam phoned, asking me to come there. Govind said, ‘Come. You can just enjoy yourself with us.’ Once I reached there Shyam said, ‘Call the makeup man.’ When I asked why, he said: ‘Did I call you here to eat for free? I’ve called you for work.’ I said, ‘You know, you can see my face, how it is… ’ Shyam still insisted on getting my make up done, and immediately after took a picture and showed me. ‘Can you see any difference? No, right? I need Sulabha just as she really is. Come. Let’s start work.’ So that’s how I ended up acting in Kondura. Shyam later said he had really wanted a very natural look anyhow.

You directed a children’s film called Raja Rani Ko Chahiye Pasina.

I used to direct children’s plays. This was one of them that Tendulkarji had written. It was a Marathi educational play that was later translated into Hindi. So V. Shantaram saw the play and said, ‘I want to make a film based on this play. Will you do it?’ But I had never directed a film so I took a month or so first, to figure how to adapt it from theatre to film. It had to be like the play, but it couldn’t be exactly like it. So Tendulkarji and I reworked the script. The story is that the king and the queen don’t have any children. And someone says it’s only when you sweat that you’ll have a child. So they want to sweat and to be able to do so they travel, search for the answer… in the end they learn that without work it’s not possible to sweat…

We went to Shantaram’s office. It had huge doors and there was his famous cage(a golden cage with a parrot in it)outside the office. Shantaram looked at the script and said, ‘However you want to do it, go ahead.’ And on the first day, when we took the first shot, he was watching us from his office on the first floor. It was very sunny and he had this flat hat which he sent down to me. So I wore the hat and began work. Someone took a photo of me in that hat. Someone also said, ‘You are wearing V. Shantaram’s hat. You are making his picture. So now we need to salute you too.’

You have worked with Smita Patil in several movies. What are your memories of her as a co-actor or as a friend?

Smita wasn’t exceptionally beautiful but she was very attractive. She was seedhi saadhi (simple) and didn’t really bother about how to be stylish, how to dress. But she was a fantastic actress. Her parents were social workers and right from childhood she wanted to help whoever she could. Her mother had told me of an incident from when she was a nurse and Smita was four or five years old. Smita had heard about a woman in the hospital in which her mother worked, who had had a third daughter and so no one was coming to see her (because she had given birth to yet another daughter, instead of a son). So Smita’s mother had made tea and Smita kept a portion of it separately. Her mother asked whom she was keeping it for and Smita told her about the woman who had given birth to a third daughter. She was crying about this. So she went to visit the woman with her mother.

In Pet Pyar aur Paap, she was playing a garbage collector. On set there was a hut and the garbage that piled up outside it was very dirty. Smita put her hand in it and I said, ‘Don’t do that. There’s no place to wash your hands. You want to do your work well, fine, but don’t put your hand in dirt.’ She said, ‘Sulabha Tai, do you know where the director is standing? Right in the middle of a puddle, because that’s where the camera is. He’s going to take a shot of me. I shouldn’t be complaining.’

The last film I did with her was Bheegi Palken. After my last scene in the movie with her was done, as I was leaving, I noticed Smita searching for something frantically. She said, ‘I had kept my mangalsutra here and now I can’t find it.’ Her shot was ready and waiting so I gave her my mangalsutra, saying she could return it whenever we met next. But after this she fell ill. I went to see her in the hospital and I remember there was a bottle there (near her bed). I asked her for what it was and she said, ‘Cough medicine.’ I said, ‘But you don’t have cough.’ She said, ‘I don’t have a cough, but I’m not getting any sleep that’s why I’m taking it. It’s good if I can get some sleep.’ I remember saying, ‘It’s not good at all. You’re having a child. Don’t do this.’ I knew there were personal problems she was going through, even though she didn’t tell me herself. She used to drink a lot of the cough syrup, and then sleep. Then her son Prateik was born. He was only 10 days old when she passed away.

After she was gone, I got a phone call from her mother. She said, ‘Smita has left something for you— tied in a cloth. And on that she has written your name.’ I had forgotten about the mangalsutra by then and said, ‘There was nothing of mine with her.’ But she said, ‘Your name is written on it, so it must be something.’ She gave it to me, I opened it, and in the cloth was my mangalsutra.

Your last Hindi film role was in English-Vinglish. How did that come about? Also, your character was different from the typical mother-in-law that we see in the movies. Do you feel women are getting more interesting parts in mainstream Hindi cinema?

There are lots of different roles nowadays for women. Gauri (Shinde, the director) just said: ‘I have faith in you, and there should be one Marathi (actor) in this film (because the central family in the film was a Marathi family). It’s a small role.’ But there’s no such thing as a small role. She never told me what to do. She just told me about the role and the scene. Everyone likes this film, I feel, because everyone relates to it in some way. And true— I’m a different kind of mother-in-law in the movie.

What has been your most challenging film role so far?

I got a call from NFDC about a Kannada film where the director (Vasant Mokashi) wanted me for the main role. That was Gangavva Gangamayi. It won 16 awards. The character I played, the lead, was an old woman. I didn’t know one word of Kannada and I wasn’t comfortable. I said I couldn’t do it in the beginning. After four days the director came to my house. He said, ‘Please do it.’ I said, ‘How can I do it? I don’t even know the language, and you want me to do the main role.’ He said, ‘This story has been written by my father. It’s won an award. My mother said, ‘Give this role of Gangavva, to this Marathi actress that I’ve seen. She should do it.’ I don’t know why my mother said that and what work of yours she’s seen. But I’m doing this for her. How many days will you take to learn to speak the language?’ I told him it would take me two months, but first I would need the script and to find a lady who can speak both Marathi and Kannada.’ So they found a professor who knew Marathi and Kannada very well. The crew wrote my lines in Devanagari and they recorded them for me so I knew how to say them. I, on my part, worked hard at all of this for one and a half months. But I still didn’t have any confidence. I told them during the shoot, ‘Next to the camera, there must be a light cutter (a black sheet on a stand, to cut out excess light while shooting) with my lines and cues written in big letters. I won’t read it, but I need the confidence of knowing that that is there.’ They agreed to this.

I remember there was a big scene, where my character says something very angrily. While talking, I looked from left to right, and the camera was on a trolley. It was moving from a long to a close to an extreme long shot. After I had finished, the cutter had to be moved between shots. But while doing the next shot I realized that there was no cutter there. And so I got nervous and forgot my lines and began to speak in Hindi. And the people who were watching started laughing because they didn’t know that I was Maharashtrian. Whatever they had heard till then was in Kannada— so they thought I knew Kannada. Then the director made everyone get out and did a tight close up.

I had said to the director at first that I’d do it but they’d have to get a good artist to do the dub. So they had arranged for a big Kannada actress to do it. But then I tried to do the dubbing myself. After listening to it for one or two months they said, ‘Sulabhaji’s done very well. Her voice can be used.’

Now, I did another film and there was a Kannada actress working on that. And she said to me, ‘Haven’t you heard, a Maharashtrian actress has won an award for a Kannada film. I haven’t seen the film but the actress who played the role of Gangavva, she’s Maharashtrian. And still I got second place.’ She didn’t know I was the same actress.

‘The rest is history.’

SpecialDecember 2013

By Alyssa Lobo

By Alyssa Lobo

Alyssa Lobo is Junior Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture.

By Nishant Shukla

By Nishant Shukla

Nishant Shukla is a mumbai based visual artist. He pursued a master's degree in Photography at the University of West London. His personal work has been exhibited at Fresh Faced and Wild Eyed, 2009 at The Photographers’ Gallery London, Photomonth 2010, Watermans Gallery and the PM Gallery in London. He has also showed his work at the United Art Fair in New Delhi. Nishant currently balances his time between photographic commissions and video work.