Rohini Hattangadi, 62 shot to fame with her portrayal of Kasturba Gandhi in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi for which she won a BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role in 1982.

She has acted in several films in parallel cinema, working with directors such as Govind Nihalani (Party, Aghat ) Mahesh Bhatt (Arth, Saaransh ) and Saeed Akhtar Mirza (Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastaan, Mohan Joshi Hazir Ho, Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyoon Aata Hai). She has won a National Award for Best Supporting Actress for Party.

The acclaim for her performance in Gandhi, however, had an undesirable side effect. She was constantly offered the role of the hero’s mother in several mainstream Bollywood films during the eighties and nineties. Among the most noteworthy of these performances is Suhasini Chauhan, Vijay Deenanath Chauhan’s mother in Agneepath. Hattangadi was 39 at the time, nine years younger than Amitabh Bachchan.

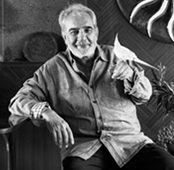

Aside from her work in films, Hattangadi has enjoyed a prolific theatre career. She and her husband Jaidev, a theatre director, began their careers at the Marathi theatre group Awishkar and went on to found Kalashray, a theatre group and centre for research, education in arts and talent encouragement in Mumbai. In 2004, she won the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for her contribution to Indian theatre. Today, she continues to act across film, theatre and TV. This interview takes place at her house in Bandra.

What’s it like to be an ‘character actress’ in Bollywood, where there has been a limited scope for the kinds of roles women can play. For instance, in many films, one sees female characters only as the heroine, the vamp or the mother…

I entered mainstream Hindi cinema playing a mother because of Gandhi. I was some 27-28 years old, so it was quite late to be a heroine, maybe, and run around trees. So I was stamped with the mother’s roles or supporting roles. It was very rarely that I got to do the main character in a film. In parallel cinema I have done main characters but in commercial cinema it was very difficult to have a heroine’s role. Only once, for Saaransh I was nominated (for a Filmfare Award) in the category of ‘Best Actor, Female’ but I didn’t win. The term ‘heroine’ is associated with younger characters and I never did such roles. And my experience with getting a role is that while sometimes directors are adventurous, the producers never are. They are not willing to take a risk. Once they’ve slotted you in a category you stay there. So I never got out of the ‘mother’ slot, whatever the reason may be. So in between I began saying: ‘Please give me a negative mother!’

Also, my characters rarely had a husband present in the film. And when the husband’s character was there, my character was not very strong. Since I was portraying strong characters well I was mostly cast as a widow who had single handedly raised her sons and daughters. And then, a few times, I got to do negative characters or comic characters. Like, with Pukar, it was a comic character, an interesting character. Then in Lajja, though the character was very small, it had grey shades.

So that was it. They don’t want to take risks. And these people have not spared any actor. For that matter, even Amitabh Bachchan was slotted as the angry young man. Then he was the angry old man too. It was only very recently that he started venturing into different characters. Like his role in Black. Even Amjad Khan, after playing Gabbar Singh, was mostly a Gabbar Singh. Amrish Puri was almost always the villain.

The parallel cinema at least had a greater variety in female roles.

Yes, yes, it did, it did. I’ve done a lot of parallel cinema also, like Party. Party was a film that revolved around one evening and the characters— they are brought out very well. As the evening goes on you get to know more about those characters. My character is a has-been theatre actor and she has crossed 30, so she’s not a heroine anymore. She has left acting for the love for her spouse, who’s a writer and she’s with him. And now she is finding that he has lost interest in her. So she’s like, ‘What do I do now?’ She gets to know about the whole falsity of the relationship and she’s staying in that.

Another such film was Arth. Where you had a role as the maid.

Arth was towards the beginning, immediately after Gandhi. I never knew who Mahesh Bhatt was, or anything about the Hindi film industry. Only Kiran Vairale I knew from theatre and she said, ‘Mahesh is looking for you and I will give you his address and you should go and meet him.’ Shabana (Azmi) sent me a message: ‘Don’t say no to him, it’s a good role.’ So I went and met him and it was the maid’s role which I think I liked actually. I liked the whole soul of that character because— they are so near to our lives, such characters. I remember my maid when I was a child. She was not formally educated. Her daughter was two years younger to me, she was studying in the same school as mine. So my mother used to keep my clothes, my school books, my uniformsthat I had outgrown. She used to keep those and pass them to her. Then afterwards I came to know, when I left Pune for the National School of Drama (NSD), that my maid’s daughter, she went on to do the Montessori course and she was teaching in Montessori. So she had achieved something being a maid’s daughter. So I had that in mind. And when I got to do this role, I immediately related to that.

How did your character see the central relationships in Arth— the love triangle between the characters of Kulbhushan Kharbanda (the husband), Shabana Azmi (the wife) and Smita Patil?

She’s relating to her madam. She’s a silent spectator of the agony she’s going through. That’s why I like that one scene where I’m sent to give the keys to Smita. And that was I think the interval scene and I suddenly turn and tell her: ‘Aree roti chin lo, khana chin lo, mard kayko chinti? (Steal roti, steal food, but why steal someone’s man?)’ That was maybe society’s reaction and also a result of not knowing what the ‘other woman’ is going through. And that plays on her mind ultimately.

How did you begin acting?

Right from my childhood, in Pune. My mother was very fond of sending me for dance classes, on an amateur level. My guru Surendra Wadgaonkar was a kathakali dancer and his wife was a bharatnatyam dancer. So we learnt bharatnatyam and katahakali. Whenever somebody used to call, ‘Rohini dance karti ho na? Chalo aake naachke dikhao.’ (Rohini dances right? Come on show us how you dance), I used to get up and start dancing. I was in school then, in the 5th or 7th standard maybe. Then, because of my dancing, I got a role in a children’s play which our teacher was doing out of school when I was in the 8th standard. I had 3 dances and a character to play: the character of a prince’s friend. So that’s how I got into acting.

Also my father, Anant Oak, was an actor and theatre director himself. He had worked in Bombay theatre with Vijaya Mehta in 1955 and with Arvind Deshpande. But his involvement came much later. I had started doing theatre during the vacations. And I liked it— when I would to go on stage and render dialogues and when the children, the audience would react to it. So afterwards, when my father was doing a play for state competitions, and he was not getting an actor for a particular character, my mother pestered him to try me out.

Ultimately I did that role and things went well from there. I eventually won the regional silver medal for best actress. And that’s how I started doing theatre seriously, because of my father. He was my first guru, you can say, into theatre. He initiated me into parallel theatre. Commercial theatre came afterwards. I went to NSD in 1971.

And how did you decide to do films?

When I was back from NSD, I started doing commercial theatre in Marathi. Filmmakers were just beginning to explore a different kind of cinema at that time. At the same time Naseer (Naseeruddin Shah), who was one year senior to me, had graduated before me from NSD, went to FTII and then was in Bombay working with Saeed Mirza, his batchmate. So when Saeed Mirza was making his first film (Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastan), he got to know of me as an actor from NSD. So he asked me whether I could act in it. And I said ok. And then we did a second film, which was Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyoon Aata Hai. And then I went on to do Chakra. At that time I was doing theatre and films together. And then I got Gandhi. So my fourth film was Gandhi.

Which do you prefer— films or theatre?

Well my first love is theatre. And I love theatre because you’re constantly exploring the medium. Even if your script is the same you perform in front of different audiences, in different places, your mindset is different every day, you have to cope up with it also and it’s a live medium and you have to create a universe in a 40 x 40 space. That is so exciting and that’s why you constantly experiment and why theatre experiments so much. It experiments on scripting, on the style of plays, even the sets are so different. Sometimes the box set is there and sometimes only a lamp can, as if by magic, recreate the living room. So it is constantly changing. And while performing I get the insights of different people because you get to portray so many different characters.

How did you get your role in Gandhi?

It was out of the blue. Dolly Thakore was assisting Sir Richard Attenborough in meeting all the actors and actresses in Bombay. One fine day when I returned home after touring with my play I found a note, that Jaidev (Theatre person Jaidev Hattangadi, her husband) had left for me saying not to keep any work as we have to go and meet Sir Richard.

Jaidev was well read, well informed and I was completely the opposite. He had said, ‘Rohini, there is a film being made on Gandhi and Dolly called us to meet Sir Richard Attenborough. You’ve seen The Great Escape? He was in it.’

Then we met him and chatted for an hour or so over a cup of tea. And the next day I got a telegram from Dolly—I didn’t have a phone then—saying I should call her urgently. So I did and she said I would have to go for a screen test to England. And at that time my play was running so we hardly had two consecutive days free. So I said, ‘Mera play hai, yeh kaisa ho sakta hai? (My play is there, how can I do this?) I can’t go.’ Dolly said, ‘Rohini are you mad? Please go.’

And then I went to Kamala Kassara whose play I was acting in and he said he’d manage till I returned, but that I’d have to be back in a week.

At England, they gave us one scene, the cleaning the latrine scene, where Baa (Kasturba Gandhi) refuses to do it. And then I was made to act with Ben Kingsley because they had determined three pairs of six people whom they would decide from. They had screen tested and paired us themselves— me with Ben Kingsley, Smita Patil with Naseeruddin Shah and Bhakti Barve with John Hurt. They did screen tests for two to three days. I did my screen test and saw it when I was there and I was very unhappy with it. Still when I was back Dolly told me, ‘Rohini, they’ve said to cut down on your weight.’ I asked why. So she said, ‘Richard has asked you to cut down on your weight because you have to portray a character from the age of 27 to 74. So they want to see you really patla (thin).’ So the rest is history.

It was a big production and one of the first few international ‘crossover films’. What was that experience like?

Actually when I was selected for Kasturba I didn’t know Mahatma Gandhi’s life very well. So first thing I did was stop at Mani Bhavan and buy (The Story of) My Experiments with Truth and his autobiography.

The vastness and magnitude of the whole project didn’t dawn on me till I started shooting for it. When I started working on it, after they gave us the script, was when I began to understand— till then it was just another character. My theatre background helped hugely because in theatre you have to be very disciplined. If I had worked here, in Bollywood, first, it might have been a real problem but because of the theatre background, the discipline the role required came naturally.

They had called me on the 1st of November, whereas we were going on sets on the 30th of November. So I had one month to do two things to prepare the role. One was spinning, using the charkha, and the other was improving my English, because, I was from a Marathi medium school, in Pune. So I had to undergo elocution lessons.

Meanwhile Ben Kingsley was also taking the charkha lessons and he was doing yoga. And then we had to work on the script as well and research it well because there were so many different incidents which were clubbed together in a sequence of scenes. So we had to find out which year a certain incident was, what the age of the character was in that year was and, consequently, how things should appear in a scene. The makeup man, hairdresser and I worked that out together for my scenes. Because there had to be a slow transformation from young to old, to 74 years.

The whole thing began at the end of November and then I realized how organized it was when for my first shoot I was 5 minutes late for makeup and I got a call. We were staying at the Ashok hotel in Delhi and they had taken some rooms there and set up make up department, costume department… So I got a call from the makeup department, on the hotel hotline saying, ‘Rohini, you’re 5 minutes late.’ So I would be 10 minutes early from then on.

When you won a BAFTA for Gandhi, what was that like?

Well, at the time I knew the character has gone down well. Richard liked it, everyone liked it. But I never imagined that I was going to be nominated, because I was not really aware of… You know, nowadays everybody’s aware of the Oscars, Cannes and the Berlinale. But at that time I was not aware of anything. Indo-British Films sponsored me to go to the award function. I was in England for a weekend. And that award function was also very different from what we used to have here. Filmfare was the most coveted award function in India, at that time, in the eighties. And I had written a piece also on that award function, on how different it was from what we had here at that time. First there were the nominations, and then one person getting the award, it came afterwards. They would announce all the actors and actresses. The nominees from each film were sitting on their respective tables. There was a Gandhi table, then a Tootsie table, an E.T. table. And then, whoever was nominated, for instance our writer was nominated, Sir Richard was nominated, Ben was nominated… so everybody’s name was there on the table.

Coming back to an entirely different experience, which is mainstream Bollywood. You played Amitabh Bachchan’s mother in Agneepath. I realize that you are younger than Mr. Amitabh Bachchan…

Yes. I’m younger to most of the actors whose mother I’ve played in the movies. Right from Jeetendra to Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan, Vinod Khanna… Only Raj Babbar, whose mother I also played, is younger to me by one year maybe. And Naseer is my age, or maybe 1 year elder to me. So I’m really… On average all of my sons have been around 10 years older to me.

Agneepath, released in 1990, was a culmination of eighties Bollywood, the angry young man was in full swing. How did that role come about?

In between there was a patch when I said, ‘No! I’m not going to do mother’s roles.’ And my secretary was trying to pacify me: ‘Rohini, don’t behave like this, roles won’t come after this then.’ But I still said no to three or four films. I said, for instance, ‘No, I will not play Feroz Khan’s mother… ’

Then there was this film called Sultanat which I had said no to too. That was directed by Mukul Anand. So when Agneepath came, also directed by Mukul Anand, my secretary calmed me down. So I said, ‘Okay, it’s fine, I’ll do it.’ So Agneepath was one of those ‘okay’ kind of films. So I went to Mukul Anand and he narrated the story and all.

And I liked it because that was the first time I was hearing a story which had different characters which could all be remembered. Otherwise all Amitabh Bachchan films were: Amitabh, heroine and villain. And that’s all. There were no other characters whatsoever. Agneepath was the first time I could remember even the police commissioner, I could remember the sister’s character, I could remember Mithun’s character, even the Pathan, that policeman… each and every character was so well defined and yet in its place.

I had done Shahenshah before that with Amitji. So in Shahenshah I could see him having fun on sets. Once I asked him on the Agneepath set, ‘What do you expect from this? I can see a totally different approach to the character.’ So he said, ‘The thing is Rohiniji Shahenshah was a fun film so it warranted a different approach. Here I want people to just sit, slightly alert, on the seat, not leaning back. Just lean forward and look at the film.’ So he’s that kind of a person and that explains the way he’s handling his characters now too. But at that time the the roles he was getting, like in Jaadugar and Toofan, made me wonder what he was doing, despite being such a good actor. But that’s Bollywood.

Have you seen the remake of Agneepath? What did you think?

Yes. Amitji’s Vijay Dinanath Chauhan in Agneepath was a totally different interpretation, altogether larger than life. And that time, that was the need of the hour. Hrithik Roshan treated Vijay not as a Don but as someone trying to be human, a middle class common man who is trying to fight it out. That’s what I felt. But, that said, the portrayal of all the characters was not coherent in the second Agneepath. I found (Sanjay) Dutt’s character to be larger than life, for instance. If it would have been on the same page that would have been a marvelous attempt. But because it was not it seemed odd. For that matter, Rishi Kapoor’s character was down to earth and real. But somewhere Sanjay Dutt’s character wasn’t fitting in. Also in our version, the first one, the characters of the mother and sister were utilized. The mother’s character had a motivation— that she wanted the son to transform, become ‘good’. Here the mother’s character wasn’t fully developed.

What are you working on right now?

My Marathi serial. I’ve shot a Telegu film. Then Jagdamba, a play I’m trying to revive. The play is on Kasturba only.

‘The rest is history.’

SpecialDecember 2013

By Alyssa Lobo

By Alyssa Lobo

Alyssa Lobo is Junior Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture.

By Nishant Shukla

By Nishant Shukla

Nishant Shukla is a mumbai based visual artist. He pursued a master's degree in Photography at the University of West London. His personal work has been exhibited at Fresh Faced and Wild Eyed, 2009 at The Photographers’ Gallery London, Photomonth 2010, Watermans Gallery and the PM Gallery in London. He has also showed his work at the United Art Fair in New Delhi. Nishant currently balances his time between photographic commissions and video work.