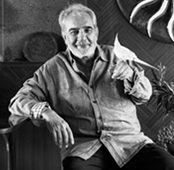

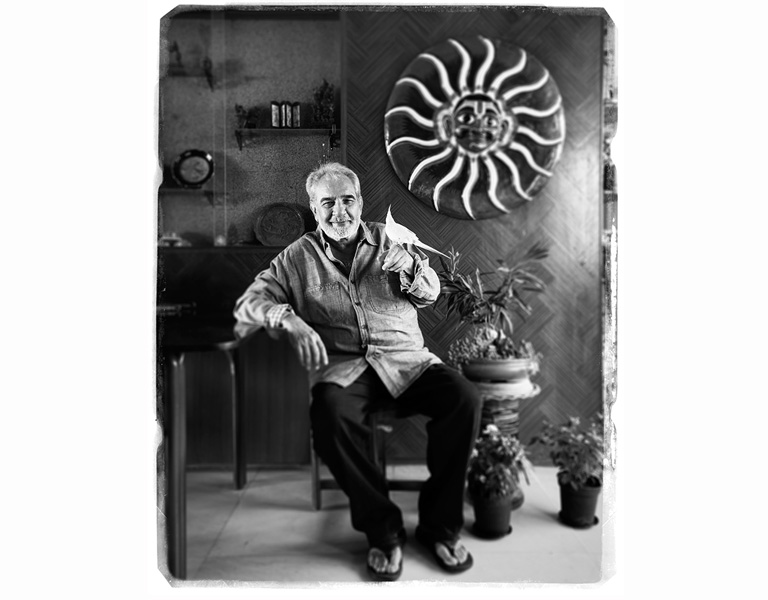

Kulbhushan Kharbanda, 69 is probably most recognizable to regular moviegoers as the villain Shakaal in Ramesh Sippy’s multi-starrer Shaan (1980). He has also done character roles in several other blockbusters of the eighties, nineties and 2000s such as Silsila (1981), Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985), Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar (1992), Hera Pheri (2000). He has balanced these with powerful, nuanced performances in parallel cinema, from early on in his career with roles in films such as Manthan (1976), Bhumika: The Role (1977), Arth (1982). More recently, he has been a part of internationally acclaimed films such as Lagaan (2001), Monsoon Wedding (2001) and Deepa Mehta’s Elements Trilogy (Fire, Water and Earth). His prolific career, which also includes roles in Punjabi movies, was brought to an abrupt pause in 2011 when he was seriously injured after falling off a horse while filming. The accident could not limit his work for long. Kharbanda worked his limp and use of the cane into the role he essayed in his comeback film Midnight’s Children (2012), Deepa Mehta’s adaptation of Salman Rushdie’s iconic novel.

Last year he came back to the stage as well, after 18 years, as the protagonist Rajadhyaksha in the Hindi adaptation of Mahesh Elkunchwar’s Marathi play Atmakatha. An avid traveller, Kharbanda was watching the Travel and Living Channel before we sat down to chat. His pet parrot nips gently at each of our trousers before settling on his shoulder while we discuss his work. This is not a cause for concern. Shakaal had sharks.

You became famous in the mainstream with your role of Shakaal in Shaan; Could you share a few memories of working on that film?

I don’t have many, or maybe I don’t remember now. My involvement was very short really. I was working with Mr. Ramesh Sippy, who is so professional, so methodical, that we shot my portion in two to three continuous schedules and it was over. I was not involved from the very beginning, I came in towards the end. They left that portion of mine, I think, and shot the rest of the film. So I don’t have many anecdotes from that film.

Before you took on this role of Shakaal, you had done a lot of parallel cinema. How did this mainstream film come about?

For me it doesn’t matter. I was offered my first role by Shyam Benegal, so I kept on doing films with him and then through his films, these commercial people recognised me or they recognised a particular character. And Salim-Javed saw the film and they recommended me to Ramesh Sippy and that’s how it happened.

You had been quoted in an interview, saying that you wanted to make the character of Shakaal edgier, like what it might have been a Bond film. But that didn’t happen. Why?

When Rameshji and me were discussing the character, I was thinking about it in a particular way but he said, ‘Don’t be too edgy because in our cinema we understand a particular kind of character’. And I think what he said was correct. That a certain consistency, to make the characters recognizable, was required of our cinema at that time.

What did he mean by ‘edgy’?

Edgy would mean making it more colourful, creating a character which was unusual compared to the usual villain, to make it more subtle— to take the character ‘to the edge’, so to speak. He (Ramesh Sippy) said: ‘Look. We always believe in black and white. And our audience— they love it. So one should be consistent when it comes to a particular character.’ I think I must have mentioned somewhere. It was not a big thing. In the beginning I just… He was absolutely right. I agree with him.

Do you think the idea, that way, of what a villain is has changed in our cinema? There are shades of grey in our heroes too. Does that apply to our villains?

I should talk to you actually about this film I saw, where there was no villain, I think…

Which film?

My daughter keeps showing me them on DVDs. And among the recent ones I haven’t found villains…

Current Hindi films?

Yes, I haven’t seen any villain as such. Because I think films have become more daring now and more experimental.

Is there a film which holds a special place for you either personally or professionally or in terms of a breakthrough in craft?

When you’re doing a film, everything’s important but sometimes it happens that in a film you just sort of come to know which kind of film you’re working in. You know what’s in the director’s mind. You know that people will say: ‘Oh, that film you did— it’s the same thing, nothing different.’ And you then feel it’s very easy.

But sometimes, if the director is serious, he makes you serious, and then different things come out all together. Most of the directors now, I believe, are more serious about their work. They don’t quote another scene, or another film, for you to imitate. There’s none of that.

For example?

For the last two years I’m totally out of touch because I met with a very bad accident. I had three operations and I’m still recuperating and I’ve done only four or five films since then.

You’ve done Deepa Mehta’s Midnight’s Children

That was just after my accident. A stick was given to me to walk.

That was worked into the script…

Yes, when I said, ‘I won’t be able to make it,’ she (Deepa Mehta) said, ‘We’ll give a stick, you’ll have to come.’ They were shooting in Sri Lanka. I went twice.

Did you read the book before shooting?

I had read the book long back. They keep sending scripts, those people. Sometimes you get tired, because they send every little change in script to you— yellow pages, red pages, green pages. It could be the 10th version, or the 11th version…

You’ve worked a lot with Ms. Mehta. You’ve done both parallel and mainstream cinema, you’ve done international films. How do they compare?

Well, when you’re working with Shyam Benegal, he goes into a lot of details.

Was he as detailed as the team of Midnight’s Children with his scripts?

No. He gave you a final script and everything would be there, but we would talk a lot.

Discuss the character?

This not with him only. Now the youngsters are coming up with a lot of new ideas that they really want to work on and I’m not sure if the industry will be changed or not, but if it changes it will be for the better, it will be more professional.

Do you have any younger directors that you want to work with? Or is it that because of your health…

No. My health is absolutely fine but because of the accident I had, word is out that I am unwell.

So you are fit and ready to…

Yes, I’ve done four to five films. I’ve done a German film.

Which one was that?

Junction Point. It’s an English name, but the German name is something else (Fernes Land).

And the director of that is?

It’s a Jung’s Production. It’s a German-French production, The French director is of Indian origin. I’d done some shoots after the accident. So those people are approaching me, but there’s not much from this industry. I think that it’s because the word is around that I’m not well. I don’t know how to tell people: ‘Look I’m alright.’ How to project… (that I’m healthy).

One of your earlier roles was in Mahesh Bhatt’s Arth. What was it like working on that film? What kind of conversations did you and Mr. Bhatt have on the character…

Nothing much. He said basic things. I knew Mahesh very well by that time. It’s a simple story. There are three people. They’re nice people. Nobody’s wrong but it happens in life. So a situation arises (an extramarital affair, a love triangle) and where could the situation lead? We started thinking about it from there— till the interval. We didn’t know where to take the film after that. I think this is a very difficult subject, that it’s difficult to justify all the three people. They were each justified but they were each sandwiched by the situation they were in. But then later on the easy way out was taken, because it was made from the wife’s point of view.

So that’s how the story was shot. Though I feel it was very easy to make it from the wife’s point of view because, in my opinion, the wife is already accepted by society. Society’s already sympathetic towards her. But I think the challenge would have been if you made it from the point of view of the mistress wouldn’t it?

Or the husband.

Yes, but well I’m not mentioning my name (laughs).

Another film that you did was Yash Chopra’s Sisila

Sisila was a small role.

But it was an important role because your role does bring the major conflict into that dynamic. It pushes things forward. But taking off from what you said, nowadays if you talk to actors a lot of them ask about the screen time they’re getting. Was that important for you?

No, because by that time I had done a film with Yash Chopra, which I think nobody knows about. It was Nakhuda. It was Yash Chopra’s production, directed by his chief assistant, I think (Dilip Naik). While making that he said, ‘Do this also.’ When I was going to a film festival, he said, ‘Live on my expenses there only.’ That’s how I did the role.

What was the experience of working on Lagaan?

With Lagaan, again, Ashutosh (Gowariker— the director) is very serious. He’ll come to your place, sit with you and discuss not once or twice but thrice or four times whatever he wants. At Aamir’s place, there were many readings before the film started. The whole script was read many times. Not me, because I was playing a king, but other actors were living like the villagers, they started really living in the village, most of them, before and during the film— to get into character. I saw this kind of rigour last when we made Manthan with Shyam Benegal. Those were the days when I last remember us doing things like that.

Before you had joined films you were a theatre actor. Which medium do you prefer? Also how do you think theatre shaped you as an actor?

In theatre you have to do your job and theatre is very particular about that. There can be no nakhra (airs) in that. The day of the show you have to be there, whatever happens. Because theatre has a kind of inbuilt discipline where you are not being forced to follow the discipline. I think every profession has a different kind of discipline. But I’m just using big words, making it a big thing. Why is that necessary? It is basically my hobby. I love theatre, I used to do it and still, you won’t believe, just now, I did one play (Atmakatha) after 20 years.

Yes, it was your return to stage.

Because while I was sick, I thought this is the best thing and that I must go back and test my reflexes again, and my memory. For 70% of the play I am talking. We’ve done shows in Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi and Jaipur. It was a good test for me. The ultimate test is theatre.

Interviews by Alyssa Lobo. Portraits by Nishant Shukla.

‘The rest is history.’

SpecialDecember 2013

By Alyssa Lobo

By Alyssa Lobo

Alyssa Lobo is Junior Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture.

By Nishant Shukla

By Nishant Shukla

Nishant Shukla is a mumbai based visual artist. He pursued a master's degree in Photography at the University of West London. His personal work has been exhibited at Fresh Faced and Wild Eyed, 2009 at The Photographers’ Gallery London, Photomonth 2010, Watermans Gallery and the PM Gallery in London. He has also showed his work at the United Art Fair in New Delhi. Nishant currently balances his time between photographic commissions and video work.