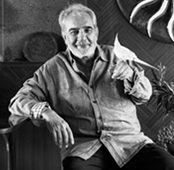

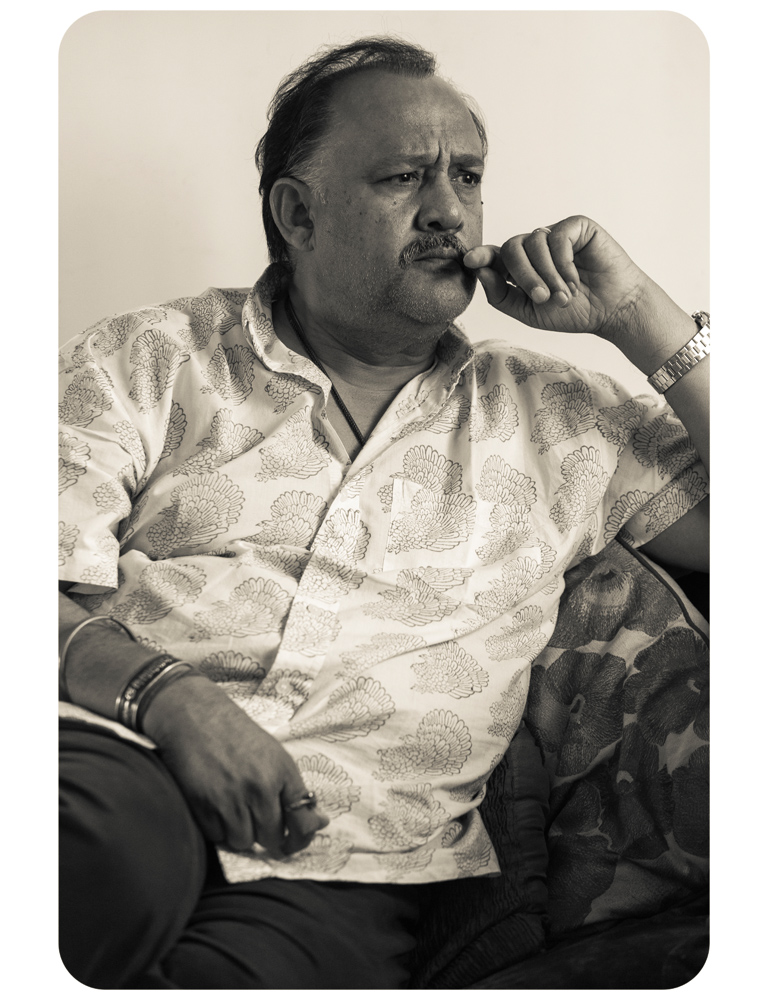

Last year, TBIP documented the work and lives of some of India’s best known ‘character actors’, through a series of photographic portraits and in-depth interviews. In the second part of that series, we present Alok Nath.

Alok Nath, 58, is one of Hindi cinema’s most recognizable ‘character actors’. A National School of Drama alumnus, he is well known for essaying the role of a kindly patriarch in many Bollywood films in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, among them the blockbusters Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (1993) and Hum Saath-Saath Hain (1999). Also, Nath has won acclaim for his turn as Haveli Ram in Doordarshan’s television series, Buniyaad.

Last December, jokes and memes based on characters played by Alok Nath—mostly on the ‘sanskaari’ (morally upright) and ‘kanyadaani’ (father of the bride) nature of his on-screen avatars—went viral on Twitter and Facebook, leading to the actor’s name trending on social media for no apparent reason, prompting online marketing case studies on the phenomenon.

The shoot and interview takes place at his apartment in Lokhandwala, Mumbai. We sit on velvet upholstered sofas in his sitting room, chatting about the highs and lows of his journey as an actor, interrupted occasionally by the snores of his pet Boston terrier sleeping on a chair nearby.

One of your first roles was in Gandhi. What were your thoughts while working on the movie with actors like Ben Kingsley, Roshan Seth, etc. Do you have any special memories of it? How did you get the role?

When I joined Hindu college, at Delhi University, I was very active in college theatre as well as in the Ruchika theatre group. I also kept doing television. After college I chose to take up acting professionally. My parents had wanted me to be a doctor—my father is a doctor—but they stopped interfering and left the decision to me once I took up humanities instead of science in college. After graduating I joined the National School of Drama in Delhi. I did three years there and even in my spare time and during the holidays continued with professional theatre and television in Delhi. Towards the end of my time at the National School of Drama (NSD), in 1980, Dolly Thakore from Bombay came to our school looking for actors for small character roles in Gandhi, being directed by the great Sir Richard Attenborough. We were told to represent the National School of Drama in the auditions and have a nice bath, wear clean clothes, shave, oil our hair… Getting the role or not was immaterial. Just to see Richard Attenborough in the flesh—he used to do theatre too and we were in awe of him—was a big high. When I met him at the Ashoka Hotel I was shivering. He looked me over and seemed to contemplate, as if he was buying a horse or cattle. His eyes were piercing into me and I was dying, frankly, because I wasn’t getting any reaction that revealed whether he liked me or not. He finally said, “Yeah Dolly looks good.” Dolly lead me into an adjacent room and said, “You’re on Alok. So this character is called Tyeb Mohammed, one of Gandhi’s associates and friends when he was in South Africa and involved in the coal miners’ agitation. So you got the role.” I said, “That’s great. But what do I do for it?” And she said, “See you look the role, that’s why Attenborough chose you.”

Later I realized I must have been chosen because I had that mean hungry look those days, the look of a frustrated theatre actor who is a committed revolutionary, a Commie theatre enthusiast.

She asked me “How much will you charge?” In those days, in television, for a play for which you had to rehearse for a week or 10 days and then record, we would get 60 rupees. Nobody had asked me what I would charge. I was just given whatever pittance and I took it. So I was like, “Madam Dolly…” Dolly was a nice looking young woman, very Westernised. And here we were, the lesser humans visiting a posh Delhi hotel, who had never been to a five star hotel suite, and my feet were like jelly but I couldn’t say that I haven’t done a film before so I don’t know how much to charge. Also I couldn’t say I used to get 60 rupees or she’d give me 100 rupees or something. So I just kept quiet. She finally said, “Okay will over 20 be alright?” I almost got a heart attack because I used to get 60 and now 20? Then she said, “Twenty thousand rupees. Should we close the deal?” My expression was like… I literally shat in my pants. I was like, “Yeah 20 is fine, it should be good.” And as I was calculating how much 20,000 rupees was, she took out a wad of notes for 10,000 rupees. “Here is an advance and you’re on.” And she made me sign some papers. So that was how I got Gandhi. I went out of the room, kept the money in my pocket, left the hotel, then took the money out and checked if they were real notes. I kept the wad under my armpits and the whole way back I took an auto-rickshaw (I used to travel by bus normally). I went home and gave the money to mom. My parents too were shocked. “Thank God you didn’t become a doctor,” they said. Because my father didn’t earn 10,000 rupees in a year.

You had only one film as a hero, Kamagni. Why were you not considered for the lead more often back then? Because I’ve seen younger photos of you. And…

Just say it. That I was good looking.

You were good looking. Why were you not offered leads?

Between Gandhi and Kamagni there were five to six years. I struggled in Bombay for almost two years and got nothing but constantly kept doing theatre at Prithvi Theatre with Mrs. Nadira Babbar, Raj Babbar’s wife. Raj, an NSD alumnus, had suddenly become an overnight superstar and signed some 30 to 40 odd films. That was also one of the reasons for this exodus of a lot of Delhi actors to Bombay. They wanted to get into the gold rush of cinema by which Raj Babbar, a Delhi theatre actor, had become a hero.

During that span of doing theatre in Prithvi with Nadiraji, a lot of film people used to come and watch our shows. I got some small roles in films. My first break was with Mr. Yash Chopra in a film called Mashaal with Anil Kapoor—it was also one of his first films—and Dilip (Kumar) saab. I played a journalist and he later gave me a role again in his film Lamhe and then I got a role in Aaj Ki Awaaz, a B. R. Chopra film.

Also, in those days the TV serial business had begun in a big way here. There was a serial made in Delhi called Hum Log, the first Indian soap. And people lapped it up like crazy. In the wake of that, more serials started getting made in Bombay. So 26 and 30 episode serials were being made. I started getting work in these serials starting with one by Basu Chatterjee, then by Nadiraji herself doing a serial and then Mr. Ramesh Sippy’s company making a serial on journalism, a caricaturist kind of show called Chapte Chapte. I played a cranky, grumpy editor, and then Buniyaad happened.

Buniyaad was a major milestone in my life which catapulted me into the acting space. I was compared to the greats of those times. The press suddenly put me on this pedestal and I got great acting offers but the condition of Buniyaad, also made by Mr. Ramesh Sippy, was that you had to give one year to them in which you would concentrate on this one show. With Buniyaad it was like I had gotten my voting card for Bombay, that read: ‘Alok Nath, Actor’.

And yet the irony of Buniyaad was I couldn’t do other work, so a lot of offers went rejected. And while people wanted to work initially, things changed. Let me explain. When I started Buniyaad I was 26-27 years of age and it started with me playing a young revolutionary, an honest, good looking guy, falling in love with a woman. Then we married, had children, they grew up, they got married, they having children and we became grandparents. All of this in one year. So in one year I lived 60 years of my life. In that one year the younger Haveli Ram, the character in the serial which got all these offers, was forgotten and at the end the image of a masterji, growing old, remained in the audience’s mind. The last shot of the serial, that has lasted in people’s memory, was that I am walking with two grandchildren into the horizon. An 80 year old man, balding, with white hair. That was the lasting image of Alok Nath.

Hum Aapke Hain Koun.. ! established you as a sort of household name. What was it like working on that film? Hum Aapke… also affected the tone of movies made in Bollywood in the nineties. Did you anticipate the effect that it had?

Before that was Maine Pyaar Kiya and even before that was Saraansh in 1983, produced by the same Rajshri Productions. In the early eighties I was doing doing a play at Prithvi called Sandheya Chaya. It’s about an old couple in their late 60s or 70s, whose children have left them for their work, staying abroad. And how they make friends with people who visit them, or the postman, or the next door servant or some person who’s dialed them by mistake. So I was playing one of the old couple and Raj Babbar was doing some Rajshri film. The people from Rajshri saw a performance. So the next day Mr. Babbar had left a message with the paanwalla asking me to call him immediately. We never had phones in those days so the paanwalla at the corner would take our messages and paid him a little extra in return. So I called Raj Babbar and he asked me to turn up at the Rajshri office.

When I landed up I was shown into a room and it was Rajkumar Barjatya, Sooraj Barjatya’s father’s room.

I introduced myself, saying: “My name is Alok Nath. Mr. Raj Babbar has asked me to come and meet you.”

He said, “Lekin par kyon (But why)?”

I’m amazed at this man. He has called me all the way from Juhu and he’s not even recognizing me.

A little agitated, I said, “Sir I am Mrs. Nadira Babbar’s actor. We have a group called Ekjute. Yesterday some people from your office came to see the play and then I got a call.”

He said, “You were in the play last night?” I said, “Yes sir.” He asked, “What were you doing in the play?” I was on the edge, also reaching the end of my patience. “Sir I was acting in the play, playing the lead.” He said, “Tum toh… lekin woh buddha tha (But, he was an old man)!” I said, “Sir, he was an old man, but I am a young man. I was acting in that play as an old man. But I am 25 years old.”

He finally recognised me, then said, “Good, good. But very sad.” He said he couldn’t give me the role. “This film we are making, we need an older man in this. But don’t worry Mr. Alok. We will always work with you.” So this is my history with Rajshri. I didn’t get that role, Anupam Kher got it. Bastard! He is just one year older than me. The only solace I got was that he must have been looking older than me. They gave me a small role in that film, a sadhu’s role. And since that film, I have worked in every film of theirs except Main Prem ki Diwaani Hoon.

Were you wary of getting typecast? Did you try to resist it?

I was aware of it, not much initially because initially there was the thirst of getting into the groove of films, being a part of this cinema world. I accepted what I was offered. Refusal would mean that the offers would stop coming, because it’s a small industry and people take offence if you refuse them.

When I was in it, I was doing it with all my honesty. By the time I realised no yaar, I think I’m on the wrong bus, I could not change things.

There were some offers, but they were not out and out different. A good man turning villain in the end, at the climax, so people will not think that he’s a villain— those kinds of roles. But even they did not work with the audience. The films worked, but I didn’t get any recognition, so I was stuck in this scenario where I would do only goody-goody roles, older roles, big brother roles, the uncle, the father, now the grandfather… It’s ok. It’s paid my bills, I’ve bought my own house, my car, I had the courage to get married, have children, give them a good education. At the end of the day, the creativity got a little dejected but survival was funded by these films.

In Hindi cinema it’s not just an actor but also a role that gets typecast. What have been the characteristics of the traditional Indian father? Is that image changing today?

A father is a person who is always looked upon as a positive person from the hero’s point of view because we have an Indian tradition of following in your father’s footsteps. So if the father is good the hero is good and the hero is always good so that means the father should always be good. If the father is bad then there are influences of that in the hero which get corrected during the process of the film. Goodness prevails. But the father figure is mostly pujya. Pujya matlab (Pujya means) a respected person. Whether he is poor or rich he is listened to, his values are cared for, his directives are obeyed.

But now, also, over the last decade our cinema has gone through a lot of churning. The whole genre of filmmaking has changed in which the family has suddenly taken a back seat. There’s less of pitaji or bauji or babuji, and more of ‘mom-dad’. The ‘Yo!’ kind of generation has emerged. And the generation gap between children and their parents doesn’t seem to show much, even literally, because of facilities such as beauty products, various options in clothing, technologies like hair weaving etc. So the parents look young and happening now, which is a kind of role I don’t fit into.

Also the heroes of the last two decades have now become fathers, though they still want to be heroes. But unfortunately their children have become heroes too, so they have had to graduate to fathers. So automatically those fathers have taken up more cinema space and left little for outsider fathers like us.

Finally, there are ‘lesser parents’, for subjects where parents are not really required. Here they are just like furniture in a film, with small roles. Maybe just passing by or with two or three scenes. Or they’re shown in albums or photographs, things like that. So, often, parents are now not an integral part of Indian cinema.

You once mentioned some particular mannerisms or thought processes that you may have that make people cast you as an older person? What did you mean?

You can’t defy age, though I did do so in the opposite direction. I played father to heroes elder to me. I’ve done almost 500 films till now in my 30 to 35 years in Bombay and almost 95% of them have been in older roles— older than my present age. And I have never said no to a film. The only film I refused around 20 years ago was one from Madras. I was asked to play Mr. Jeetendra’s father to which I said nahin (no) yaar, this is too much. He must be about 15 years older to me.

You also mentioned in an interview that you had certain goals when you came to Mumbai but you hadn’t achieved what you set out to do. If you could re-do your innings as an actor, what changes would you make to it?

In any sphere of life you have to have a goal post and you have to aim well to score. Anybody who comes in at an early age, wants to become a star, a hero. When you brush or shave in the morning there’s nobody better looking than you. You’re the ultimate. You’re Don Juan. I also came in thinking like that. But your dreams get shattered slowly, till you realise you need to face the world, face reality. This is it, accept it or leave it. At this one stage of life you’re a beggar so you can’t be a chooser because it’s a question of survival. In addition you have your family’s baggage: What the hell, you’ve left us! You’ve gone to Bombay to become a hero! What’s happening? No news! Nothing’s happening! Everybody’s shining, you’re not shining!

You get frustrated, you’re in a foreign country and you lap up the first opportunity just to prove to somebody back home that: No, no. See, that show is coming, or that film is coming. Watch. It’s me. So in doing so you accept a little defeat thinking that if you prove yourself in that little role maybe in the next film the same people will say, “He performed well, he’s a good man. He behaved well while shooting, let’s give him a better role.”

And things keeps improving too but, in doing so, time passes. To relive the past, to recycle, to change goal posts, is not easy. Obviously anybody would want to be a star, live young like a hero, sing nice songs, dance with beautiful girls, fall in love with them on screen, different women, different films, different directors. That karishma (miracle), that aura, the almost demi-god feeling… that I missed.

Bollywood can limit actors like yourself and yet you have been a part

of it for many years. What keeps you going?

With acting the biggest reward was that it was my hobby which turned into my passion and then my passion turned into my profession. And it’s paying you, with money, recognition, adulation, love and respect from the audience. The money makes it a very cushy life that way.

You’ve done work recently with well known online comedy groups. What was it like exploring this new aspect? Also, did your newfound spurt of fame on social media affect your life in any way?

Comedy is not an integral part of an Indian household. We don’t laugh too much or too often unfortunately. There is a lack of humour in our lives. When I was in school, in the initial stages of theatre, I used to do a lot of comedy in school functions because you are young and your audience is young. There was laughter, gaiety and even more slapstick, bizarre and over the top comedy.

But then seriousness happened to me, age happened, so the comic aspect of my personality got buried. People think: He’s a serious bugger, he doesn’t laugh much, he doesn’t make people laugh much.

So with people making fun of me in the social media what can I do? It’s good! It takes a lot of work to squeeze out something funny from a serious wood like Alok Nath. Why take offense? I laugh at jokes made on other people.

Now my daughter, who’s studied filmmaking abroad, was working with AIB (All India Bakchod). One evening, she seemed very serious. “Papa, they’re making sketches and caricaturish stuff on you and Kejriwal. I don’t think I’ll be assisting them on this one.” When I asked why she said, “They’re making fun of you. You’ll be saying funny things to him and your voice will be speaking from your portrait.” I said, “So what? So much of that has happened already (on social media).” She said, “Yeah but doing it to your own father, I’m not feeling quite good about it.” I said, “That’s your call. But it’s your work. I’d say go ahead and do it.”

Then I said, “Suppose I do it? Instead of the portrait, if I was there? Then would you do it?” She immediately called those people: “Hey my dad says that you can take him.” And they went crazy. Really? Alokji will do it? Then they called me and thanked me. I went and shot it and I enjoyed it. It went viral, got some 35 lakh views. Then some other company called Gray made some jokes, some rap songs to promote some project. Then the 9X people, Comedy Central, Channel V… So I said, chalo karo (come lets do it). That hidden bug of comedy is coming alive so let’s give it a different shape. I’m enjoying it.

Alok Nath Uninterrupted

October 2014

By Kavi Bhansali

By Kavi Bhansali

Kavi Bhansali is Creative Director at The Big Indian Picture.

By Alyssa Lobo

By Alyssa Lobo

Alyssa Lobo was Junior Correspondent at The Big Indian Picture.